Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on October 1, 2004

Transcript

DATE October 1, 2004 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

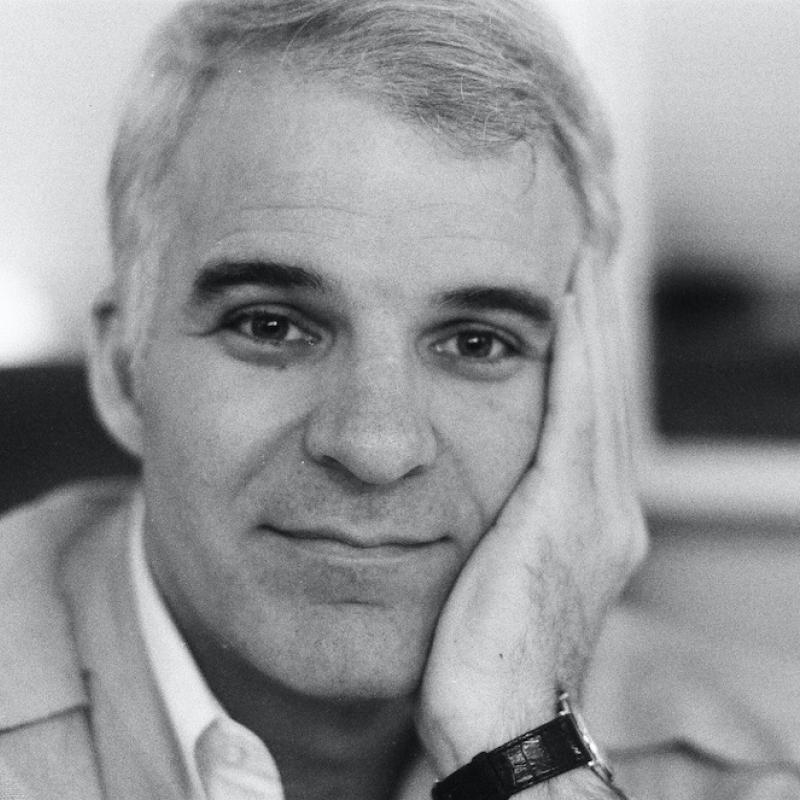

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Steve Martin on his new book "The Pleasure of My

Company"

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli, TV critic for the New York Daily

News, sitting in for Terry Gross. Our guest is the great actor and comic

Steve Martin, the star of such films as "The Jerk," "All of Me," "Roxanne,"

"Dirty Rotten Scoundrels," "Parenthood," "LA Story," "Father of the Bride,"

"The Spanish Prisoner," "Bowfinger" and "Bringing Down the House." Steve

Martin also has established himself as a novelist and playwright. "Shopgirl,"

the novel he published three years ago, was a best-seller. He's now adapting

it into a film. Martin's most recent novel, called "The Pleasure of My

Company," is coming out in paperback next week. If you're thinking it's a

wild-and-crazy-guy kind of story, it's not, but it is witty. It's about

Daniel Pecan Cambridge, a man who has so many neurotic fears and compulsions,

he seldom dares to leave his Santa Monica apartment. Terry spoke with Steve

Martin last year about the "The Pleasure of My Company." She asked him to

start with a reading.

Mr. STEVE MARTIN (Actor/Comedian/Writer): This all started because of a

clerical error. Without the clerical error, I wouldn't have been thinking

this way at all. I wouldn't have had time. I would have been too preoccupied

with my new friends I was planning to make at Mensa, the international society

of geniuses. I had taken their IQ test, but my score came back missing a

digit. Where was the 1 that should have been in front of the 90? I fell

short of the genius category by a full 50 points, barely enough to qualify me

to sharpen their pencils. Thus I was rejected from membership and facing a

hopeless pile of red tape to correct the mistake.

Santa Monica, California, where I live, is a perfect town for invalids,

homosexuals, show people and all other formally peripheral members of society.

Average is not the norm here. Here, if you're visiting from Omaha, you stick

out like a senorita's ass as the Puerto Rican Day Parade. That's why, when I

saw a contest at the Rite Aid drugstore asking for a two-page essay on why I

am the most average American, I marveled that the promoters actually thought

they might find an average American at this nuthouse by the beach.

This cardboard stand carried an ad by its sponsor, Tepperton's(ph) Frozen

Apple Pies. I grabbed an entry form and, as I hurried home, began composing

the essay in my head. The challenge was not to present myself as average but

how to make myself likable without lying. I think I'm appealing, but

likability in an essay is very different from likability in life. See, I tend

to grow on people, and 500 words is just not enough to get someone to like me.

I need several years and a ream or two of paper. I knew I had to flatter,

overdo and lay it on thick in order to speed up my likability time frame, so I

would not like the sniveling patriotic me who wrote my 500 words. I would

like a girl with dark roots peeking out through the peroxide who was laughing

so hard that Coca-Cola was coming out of her nose, and I guess you would, too.

But Miss Coca-Cola Nose wouldn't be writing this essay in her Coca-Cola

persona. She would straighten up, fix her hair, snap her panties out of her

ass and start typing.

`I am average, because,' I wrote, `I stand on the seashore here in Santa

Monica and let the Pacific Ocean touch my toes, and I know I am at the most

western edge of our nation and that I am a descendent of the settlers who came

to California as pioneers. And is not every American a pioneer? Does this

spirit not reside in each one of us in every city, in every heart, on every

rural road, in every traveler in every Winnebago, in every American living in

every mansion or slum? I am average,' I wrote, `because the cry of

individuality flows confidently through my blood with little attention drawn

to itself, like the still power of an apple pie sitting in an open window to

cool.'

I hope the Mensa people never see this essay, not because it reeks of my

manipulation of a poor company just trying to sell pies, but because, during

the 24 hours it took me to write it, I believed so fervently in its every

word.

GROSS: Thank you. That's Steve Martin reading from his new novel, "The

Pleasure of My Company."

Well, your character, although he's writing this essay on why he's the most

average American, is very not average, wouldn't you say?

Mr. MARTIN: Very not. He's a young man in his early 30s. He's unclear in

the book about his real age, which he doesn't reveal until the last couple of

pages for a reason you'll find out later. And he's isolated. He's kind of a

benign neurotic. He has certain rituals. He can't cross the street at the

curb. He has to find two opposing scooped-out driveways. He has to keep the

wattage in his apartment constant at 1,125 watts. For example, if he turns

out a light in his bedroom, he must turn on a light in the living room or

kitchen, and it's only a three-room house. And this is a story of how his

life opens up, finally opens up as he describes himself, that he has narrowed

his life down to keep everything out. In fact, his stated goal was to have so

many rules and conditions that he could control everything that was coming

into him, and then he would slowly open the doors one at a time.

GROSS: Now your character wants to get into Mensa, and he thinks they made

some kind of clerical error in leaving off the number 1 before his 90.

Mr. MARTIN: Right.

GROSS: You also wrote a piece for The New Yorker about Mensa.

Mr. MARTIN: Yes. As I say, there was precursors to this.

GROSS: Right, right.

Mr. MARTIN: And I think that I needed to start that way in order to kind of

go back to that essay, revisit that character in my head and kick it off from

where I left it off before.

GROSS: What does Mensa mean to you? I mean, it's this group of people with

high IQs who get together.

Mr. MARTIN: Right. I always saw it in this way. OK, well, you might have a

high IQ, but what have you done lately? And I think the real stroke of genius

is in what you do and not in some score. So I looked at it a little bit

cynically. I have no, you know, cynicism toward any Mensa member, but it was

just a way I looked at the world, that accomplishments are what matters and

not scores.

GROSS: I'd be interested in hearing why you want your writing to be writing

for the page as opposed to writing for the screen.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, I started writing in 19--probably--60--What?--'5 when I

wrote little essays in college that later became a book I published called

"Cruel Shoes." And then I was writing for my comedy act throughout the '60s

and '70s. And then in the late '70s, I started writing screenplays,

co-writing them with, you know, other writers, "The Jerk" and "Dead Men Don't

Wear Plaid" and "The Man With Two Brains."

GROSS: Of course, right. Right.

Mr. MARTIN: And then in the mid-'80s, I started writing solo screenplays;

"Roxanne" and "L.A. Story" and "Simple Twist of Fate." And then--I really

have written a lot of screenplays, "Bowfinger," too.

And then in the early '90s, I really got a call from The New York Times asking

me to write something on this--there was a discovery of a Michelangelo statue

here in New York City. So I wrote a little parody of that and went into The

New Yorker ultimately. Actually, the truth is, I really enjoy writing for the

page because it's an utterly different thing. You know, screenplay is

description and dialogue.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. MARTIN: And a book is really about sentences and paragraphs and their

structure and their rhythm and the use of words, the exact, precise use of

words. You know, a screenplay can be--you know, I remember one year, I, you

know, saw a little list in a magazine of the, you know, best lines from the

movies this year. And they were all, like, `Come on, let's get out of here.'

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: The catch phrases.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah. Yeah. And, you know, it's just a very different--what

your best line in a movie is is very different from a best line in a book. So

it's a completely different enterprise.

GROSS: You know, as an actor, particularly early in your career, your persona

was usually very extraverted. As a writer, like, your two novels are about

really introverted characters, and I think that's an interesting contrast.

Mr. MARTIN: Right. Well, I think actually that without, you know, being too

boring, analyzing my sort of stage act, that character--sorry to talk about

that in that way, but he was a bit crazy. He was a little--I was, on stage,

very similar to this character. Really, it's like, on stage, I was really

just expressing a perverse thought on the way the world worked. And I

remember this one bit I did was that I was so mad at my mother--I used to

scream it, of course--because she wanted to borrow $10 for some food. And you

know, there's just some kind of link here between this character, who just

sees things in the odd, odd way.

GROSS: All writers talk about, you know, facing the blank page and so on, but

it really is true that the difference between being an actor and being on the

set and being--you know, working with other people is so different than

staying at home and writing.

Mr. MARTIN: Right. You bet.

GROSS: Do you like that? Do you like that more isolated process of writing?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, you know, they complement each other so well, because, like

you say, movies are active and social and physical, and writing is solitary

and personal. And I never wanted to be an actor who sat home and waited for

scripts to come through the door. I mean, that would drive me insane, waiting

and hoping. And so I always wrote. I always did comedy, and I just like the

activity of it, you know. I just find that when I'm idle, which I always

enjoy, I always find that something comes up. Something pops up, so I'll get

out the computer and start typing. You know, having the working...

GROSS: Did you think you approach writing with a different personality than

the one you approach acting with?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, I would have to say yes, because, you know, it's just so

different. They are completely different. But I really think that my acting

has influenced my writing, because as an actor, you finally, as you get a

little better at it, you realize you're observing character. And you realize

that it's the details that make character. It's the little tiny actions. And

so in writing, I think I realize, or at least I like to pick up those details

that determine character.

GROSS: And those are the same kinds of things you have to pick up when you're

acting, too, aren't they? I mean, you're not describing them.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah, absolutely. That's what I'm saying.

GROSS: You're doing them, yeah. Yeah.

Mr. MARTIN: Right. It's from acting, but the strange thing about acting is,

it's also what you don't do. I mean, it's almost a thought process in your

head that is so expressive. So the more you can detail it in your mind, and

without, you know, what we call in acting indicating an emotion--I remember

once, the director, Herb Ross, he was mad at an actress. And I said, `What's

the matter?' He said, `Well, she supposed to be mad. She's supposed to be

mad.' And I said, `Well, she's yelling.' He says, `Yes, but anger has a

thousand faces,' and I always remembered that. It's, like, `Oh, yeah.' Some

of the angriest moments I've ever felt are when I did nothing or said nothing

and expressed nothing.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MARTIN: So there's always those choices in behavior.

GROSS: Steve Martin is my guest, and he has a new novel called "The Pleasure

of My Company."

You know, I think it's hard when you're so accomplished at something to try

something that you're new to, as you were new to writing novels.

Mr. MARTIN: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Yes.

GROSS: And, you know, when you're at the top of your profession in one thing

and then you're brand-new to something else, you can fail. You can be flawed,

and you can be very insecure. You have no track record. So did starting to

write bring out insecurities that you weren't used to? Because...

Mr. MARTIN: Oh, yes, absolutely.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. MARTIN: But there's a trick when you first start writing, is that...

GROSS: Teach it to me, please.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, you don't have to show it to anybody.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MARTIN: When you're sitting there alone, and you haven't, you know, made

a deal with somebody to deliver a book, you're really on your own. And it's

like putting your toe in the water. You can have written something, and then

you give it to a friend, or you ask someone's opinion. So you always fool

yourself, because--you know, the reason I say you fool yourself, ultimately,

you do want it to be out there, but you fool yourself by saying, `It doesn't

matter. It can be lousy. No one will ever see it if it's lousy.' And, of

course, they do see it, and sometimes it's lousy.

GROSS: So you would agree that self-delusion is an important part of writing.

Mr. MARTIN: Very, very important. I really do. I think it is. Like, I

remember the first night I previewed my play, "Picasso at the Lapin Agile," I

had never written a play. I had written screenplays. But I was in Melbourne,

Australia, and now it's 10 minutes before curtain, and all I could think is,

`What have I done?' I didn't know if there was going to be a laugh, you know,

anything. It could have been so humiliating. But then only, you know, 40

people would have seen it, and I could have gone home with my tail between my

legs. But I just like to add that I really don't have a tail. It's just a

figure of speech.

BIANCULLI: Steve Martin, speaking last year with Terry Gross. His novel,

"The Pleasure of My Company," is coming out in paperback next week. More

after the break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

BIANCULLI: Let's get back to Terry's interview with Steve Martin about his

novel, "The Pleasure of My Company." The paperback comes out next week.

GROSS: Do you write many drafts before publishing?

Mr. MARTIN: What I do is I write without inhibiting myself, and then I

will--draft is not quite the right word in my head. I go through, and I start

editing. I start reading it, and I start reading it over and over and over,

which can get very tiresome, so sometimes I'll put it down for three months,

come back, read it again. Then I'll read it aloud to myself. And then I'll

read it to my dog. And I find that reading it makes you catch every word.

And to me, every word is important, because I'm a reader who gets bored

quickly, so I need to have these sentences on the move and be interesting all

the time. So I try to catch everything.

GROSS: Is your dog helpful when you're reading to him?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, he's my audience. I'm not looking for his response.

GROSS: You just need somebody to read to?

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah.

GROSS: Did you feel an obligation to be funny when you started writing,

'cause that's what people expect of you?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, no, because the first book, "Shopgirl," although it has

funny moments, I wouldn't call it a funny book.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MARTIN: But in "Pleasure of My Company," I actually wanted the book to be

funny, and I knew that I had a character who could be funny. And, you know,

whenever you start, whenever I start even a New Yorker essay, I have the idea,

I think, `OK, what is the potential of this?' I have no idea what the

individual bits will be or moments or anything, but does it seem rich or does

it seem I'm going to run out of steam in a couple of paragraphs? And I felt

with this character, he could really keep going. And it's a cliche to talk

about the discovery of character as you keep writing, but I found that my mind

retains little details of things I've written 40 or 50 pages ago. And so

something that you wrote that was very, very casual, a little aside, a little

something he did comes back at a certain moment, and it becomes big, because

now this tiny little thing impacts something else. And it's like weaving a

web or weaving something else, a caftan, I don't know which I'm weaving. But

that's what I really like, is where the details start to add up.

GROSS: Well, you know, you've had your success in the book world and the film

world, and you've been on the best-seller lists, and you're probably the only

person to have hosted both the Academy Awards and the National Book Awards?

Mr. MARTIN: I guess I am.

GROSS: Yeah, I think so.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah. I'll have to stop any Oscar hosts from hosting the

National Book Awards, so I can keep my uniqueness.

GROSS: So, I mean, I think that would probably give you a good seat as to

some of the differences between the two worlds, the film world and the book

world?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, the differences--you know, the book world is much, much

slower than the film world. I mean, the film world is so oriented to

promotion and getting the word out in certain ways, getting the word out in

very vibrant ways and very specific soundbite ways. And, for example, I mean,

here I am talking to you for 40 minutes about my book. This would never

happen about a film, I mean, in terms of the way a film is generally promoted.

But it's the way books are promoted. They're talked about in depth, in much

slower, slower ways.

GROSS: Well, and the numbers are so much smaller, too, aren't they?

Mr. MARTIN: Right, right.

GROSS: Like a best-selling book probably doesn't come close to the ticket

sales of a mediocre-selling movie.

Mr. MARTIN: Probably, yeah. But you know what I found is that when I started

writing for The New Yorker, I noticed I got more reaction from one essay--and

I'm talking about actual reaction that I could feel, I mean people saying

things--than I did for movies. Like entire movies that cost millions and

millions of dollars to come out, and I would hear, you know, very little, or

somebody would say, `Nice movie,' or something. But these essays, they

started to--I guess because they're so intimate with the reader, they're so

intimately involved, that it stays with them longer. You know, a movie,

sometimes I walk out, I've forgotten it, you know, as I'm exiting the lobby.

BIANCULLI: Steve Martin, speaking with Terry Gross last year. His novel,

"The Pleasure of My Company," will be released next week in paperback.

Here's Steve Martin trying to impress the audience from 1978 comedy album, "A

Wild and Crazy Guy."

(Soundbite from "A Wild and Crazy Guy")

Mr. MARTIN: Hey, I'm not trying to be a big shot or anything like that, but

get my drinks half price. That's right. For every one you buy, I get two.

So I can just have about as much as I want, you know what I mean? And it

doesn't affect me.

(Soundbite of Martin falling)

Mr. MARTIN: No, I'm not on the step. OK. I have had a lot of fun since I've

been here. I do like coming to San Francisco because it is an intellectual

town, and that's kind of what I'm into, the intellectual kind of thing. And I

had a good time since I've been here. I know that sounds phony, 'cause every

entertainer comes out, and no matter where they are, they go, `Hey, it's

really great to be here!' It really sounds fake, but I am sincere when I say,

`Hey, it's really great to be here!'

(Announcements)

BIANCULLI: Coming up, James Earl Jones. When he played the voice of Darth

Vader, he had no idea how big the "Star Wars" films would become or what it

would do for his career. There's a new DVD box set of the "Star Wars"

trilogy. Also, reviews of the new ABC series "Desperate Housewives" and the

film "The Motorcycle Diaries."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: New TV show "Desperate Housewives"

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

BIANCULLI: I'm David Bianculli, TV critic for the New York Daily News,

sitting in for Terry Gross. And since I'm sitting here, let's talk some

television.

(Soundbite of "Desperate Housewives")

Ms. BRENDA STRONG: (As Mary Alice Young) My name is Mary Alice Young. When

you read this morning's paper, you may come across an article about the

unusual day I had last week. Normally there's never anything newsworthy about

my life, but that all changed last Thursday. Of course...

BIANCULLI: That's the opening of "Desperate Housewives," the new ABC series

premiering this Sunday. What changed in Mary Alice's life that day is that it

ended. She killed herself, and no one else in the neighborhood knows why,

even though everyone in every home harbors at least one juicy secret. And

just because Mary Alice, played by Brenda Strong, dies in the opening scene,

that doesn't keep her from narrating the rest of the story. She's looking at

her neighborhood now from a distant, somewhat amused vantage point, and so are

we.

"Desperate Housewives" is an hourlong soap opera that's heavy on the dark

comedy but is filled with lots of characters you can relate to as well as

laugh at. It's the best show of the new season and one of the most original.

It's also got one of the strongest and most unusual casts around. "Desperate

Housewives," created by Marc Cherry, is headlined not by one female star or

two but five. Most have starred in their own TV shows before and they all

deserve equal billing on this one. Listen to this lineup. Felicity Huffman,

who was so great in "Sportsnite," plays Lynette, a former corporate executive

who traded that life to have kids--four of them in three years. She's the

walking definition of frazzled. Terri Hatcher, who humanized Lois Lane in

"Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman," plays Susan, a suddenly

single mother coping with being unexpectedly dumped by her husband for a

younger woman. Nicolette Sheridan, a veteran vixen from "Knot's Landing,"

plays Edie, the neighborhood sex symbol and sexual predator. Eva Longoria,

who's coming to prime-time from "The Young and the Restless," plays Gabrielle,

an ex-model trophy wife with a taste for vengeful affairs. And Marcia Cross,

who is so deliciously twisted in "Melrose Place," plays Bree, a Martha Stewart

type whose outer perfection masks some inner turmoil.

Like the other women on Wisteria Lane, Bree reacts to her friend's suicide by

showing up at the wake bearing comfort food for the new widower, Paul, played

by Mark Moses. Brenda Strong, from her heavenly perspective as Mary Alice,

describes the scene.

(Soundbite of "Desperate Housewives")

Ms. STRONG: (As Mary Alice Young) Bree Van De Kamp, who lives next door,

brought baskets of muffins she baked from scratch. Bree was known for her

cooking and for making her own clothes and for doing her own gardening and for

re-upholstering her own furniture. Yes, Bree's many talents were known

throughout the neighborhood, and everyone on Wisteria Lane thought of Bree as

the perfect wife and mother; everyone that is except her own family.

Ms. MARCIA CROSS: (As Bree) Paul, Zachary.

Mr. CODY KASCH: (As Zachary) Hello, Ms. Van De Kamp.

Mr. MARK MOSES: (As Paul) Bree, you shouldn't have gone to all this trouble.

Ms. CROSS: (As Bree) It was no trouble at all. Now the basket with the red

ribbon is filled with desserts for your guests, but the one with the blue

ribbon is just for you and Zachary. It's got rolls, muffins, breakfast type

things.

Mr. MOSES: (As Paul) Thank you.

Ms. CROSS: (As Bree) Well, the least I could do is make sure you boys had a

decent meal to look forward to in the morning. I know you're out of your

minds with grief.

Mr. MOSES: (As Paul) Yes, we are.

Ms. CROSS: (As Bree) Of course, I will need the baskets back once you're

done.

Mr. MOSES: (As Paul) Of course.

BIANCULLI: Every one of these women has at least one wonderful scene in the

pilot. Some are steamy, some are funny, some are even poignant, but

"Desperate Housewives" most of all is a flat-out wry comedy served up in a

one-hour dose, with no laugh track, lots of intelligence and with the goodwill

ensemble feel of a repertory theater company. These actresses all seem to

know they've been handed something terrific here and each one not only matches

the material but adds something to it. "Desperate Housewives" is a new show

you really shouldn't miss, and this fall, those kinds of shows are precious.

Watch "Desperate Housewives" on Sunday and be prepared to talk about it on

Monday. It has the smell, the home-baked yummy smell, of an instant hit.

Coming up, the voice of Darth Vader. James Earl Jones. This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: James Earl Jones discusses his life and career

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

James Earl Jones has a voice that conveys power and authority. He also tends

to lend that voice to projects that turn out to surf some of the biggest tidal

waves of the cultural zeitgeist.

(Soundbite of "Star Wars")

Mr. JAMES EARL JONES: (As Darth Vader) There is no escape. Don't make me

destroy you. You do not yet realize your importance. You have only begun to

discover your power. Join me and I will complete your training. With our

combined strength, we can end this destructive conflict and bring forward the

galaxy.

Mr. MARK HAMILL: (As Luke Skywalker) I'll never join you.

Mr. JONES (As Darth Vader) If you only knew the power of the dark side.

Obi-Wan never told you what happened to your father.

Mr. HAMILL: (As Luke Skywalker) He told me enough. He told me you killed

him.

Mr. JONES: (As Darth Vader) No. I am your father.

Mr. HAMILL: (As Luke Skywalker) No. That's not true. That's impossible.

Mr. JONES: (As Darth Vader) Search your feelings. You know it to be true.

Mr. HAMILL: (As Luke Skywalker) No! No!

BIANCULLI: Jones was the ominous and evil voice of Darth Vader in the "Star

Wars" movies. The "Star Wars Trilogy" has just been released on DVD. This

year Jones also provides one of the voices in "The SpongeBob SquarePants

Movie." Yet in his memoir, called "Voices and Silences," James Earl Jones

talked about all the trouble his voice has caused him. In the book, he writes

about his personal life and his varied and distinguished career: on stage, in

such plays as "The Blacks," "The Blood Knot," "The Great White Hope,"

"Othello" and "Fences"; in films such as "Field of Dreams," "Coming to

America" and Sommersby"; and on TV, including the miniseries "Roots: The Next

Generation" and his own series "Gabriel's Fire" and "Paris."

Jones grew up in rural Mississippi. His family moved to Michigan when he was

still a boy. In retrospect, he credits this uprooting with causing his

stuttering. As a child, the stutter was very bad. In fact, there was a

period between the ages of six and 14 when he barely spoke at all. Terry

talked with James Earl Jones in 1993.

Mr. JONES: I did the basics. I was able to function as a farm kid, did all

those chores where you call animals. You had ...(unintelligible). I think I

had my best conversations with a dog, who was a good friend of mine and didn't

challenge me in any way. And I certainly let the family know what my needs

were, but when strangers came to the house, the mute happened. I didn't want

to confront them and I wasn't ready. I hid in the state of muteness.

TERRY GROSS, host:

Why--I mean, did you not want to speak or did you feel physically unable to do

it.

Mr. JONES: It was just too embarrassing and too difficult.

GROSS: Because of your stutter?

Mr. JONES: Yeah. Yeah. There's some serious framework around the problem

of stuttering but at the same time, although it is totally incorrect for me to

say this--politically incorrect--stutterers are very funny. I mean, when I

evoked laughter in the Sunday school class from the kids behind me because I

stuttered, I understood that. I understand how funny it is, but it's also

very painful, you know.

GROSS: Can you tell us the story of how you started speaking again?

Mr. JONES: Donald Crouch was an associate of...

GROSS: Donald Crouch was your teacher?

Mr. JONES: Yeah--Robert Frost. He was a college professor, but he ended up

in this high school because he retired. He was a Mennonite farmer and he

retired to his farm in Brethren, Michigan, and the idea that there were kids

down the road at this high school who were studying Chaucer and Shakespeare

and stuff, he couldn't stand it so he came back and taught high school, you

know. And he was the first English teacher I had--now see, I'm stuttering

again. He was the first English teacher I had and he accepted that I

didn't--I wasn't verbal. That I wasn't wasn't oral. But he didn't like the

idea that I could privately subjectively enjoy poetry and not sound it out

loud. He one day discovered that I wrote poetry and he said to me, `This poem

is so good, I don't think you really wrote it. I think you plagiarized it,'

which was a shock to me. And I could admit that it was Longfellowesque, but

it was not certainly stolen from Longfellow. And he said, `The way you can

prove it to me that you wrote it was to get in front of the class and recite

it by heart.' And I accepted the challenge and did it and we both realized

then we had a means, we had a way of regaining the power of speech through

reading poetry.

GROSS: What was it about having words written down for you that made it

easier for you to speak?

Mr. JONES: Not that they're written down but that they're rhythmic. I think

you'll find many stutterers today--I'm trying to think of the country western

singer who was a stutterer but does not stutter when he sings--but there are

many, many cases like--Mel Tillis, thank you. Thank you, Mel Tillis. And

there are many cases like that, actors, singers who don't have their problem

when they are performing. Walk off stage and you can't understand a word

they're saying. It is--has to do with the rhythm. Rhythm carries us through.

It does not--it smooths out those areas that allow the logjamming and the

stuttering to be triggered.

GROSS: So how--does the stutter come back very much for you?

Mr. JONES: You've heard it several times now. It's always with me, you know,

and I have to be careful not to talk too fast. It certainly becomes a problem

whenever I do something emotional, whether in real life or as an actor. I

give an emotional speech, whether it's positive emotional or negative, joy or

pain, and that often leads to overload and I have to be very careful. There

was a time when my acting was affected by the thing. Gladys Vaughan was the

first to notice that. She said, `When you get emotional, when your Othello,

for instance, gets emotional, I sometimes believe you less,' and it's because

I'm being too careful. You can't measure out emotion. It has a flow.

GROSS: Could you give us a sense of the kinds of exercises or the type of

training that you had that helped you find the power in your voice, because

you have a very powerful voice.

Mr. JONES: Oh, the exercises were--I got to move back a bit.

GROSS: OK.

Mr. JONES: Sooey, pig, pig, pig. Hog calling, cattle calling.

GROSS: That's something you did on a farm without having to go to voice...

Mr. JONES: My dad always said that the reason he became an actor was because,

even in grade school--and he didn't have a whole lot of it--but even in grade

school, he was the loudest kid in class.

GROSS: From calling the animals.

Mr. JONES: So he was destined to be an actor. And that's kind of true,

though. Farm kids are never told, `Hush, you'll wake the neighbors.' Farm

kids are told, `Use your voice to get those cows in here.'

GROSS: So you think you developed that power on the farm long before acting

class?

Mr. JONES: Yeah. And also--it is also genetic. I inherited whatever

resonating chambers my father possesses. They're not too dissimilar from Paul

Robeson and another actor of my generation, Geoffrey Holder. So when the

Darth Vader voice became a mystery, as many people thought it was Geoffrey

Holder as who thought it was me. And that has to do with just how the voice

is produced, you know; how it, you know...

GROSS: How it resonates in the head and everything, yeah.

Mr. JONES: Yeah, in the head and in the body. Yeah.

GROSS: In your memoir, "Voices and Silences," you devote a total of about a

paragraph to "Star Wars," to your voice as Darth Vader, and I get the

impression that it's not something you really want to call that much attention

to.

Mr. JONES: Are you kidding? Not true. It's just that I have very little to

talk about.

GROSS: OK.

Mr. JONES: Had I been one of the actors and given points, I would not only

be wealthy, I'd be probably much better known.

GROSS: You got a flat fee?

Mr. JONES: Oh, yeah. I think George Lucas, first of all, realized

he--although David Prowse was the actor he wanted, it was not the sound he

wanted, so he searched around for a technically and symbolically a darker

voice. He eventually came to me and said to Lucy, `Would Jimmy like to earn a

day's salary?' The job took two and a half hours. They paid me all of

$9,000, which was not bad for two and a half hours' work.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. JONES: None of us knew what we had, you know.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. JONES: And that was fine. Almost, not out of embarrassment, but out

of his traditionally--his non-traditional traditional capitalism or lack of

capitalism, George gave me a Christmas bonus that amounted to the same amount

of money. But I was just acting as special effects. That's all that was. At

the same time I was--having done "The Great White Hope" film, I'd become a

member of the board of directors of the Oscar board--you know, the Academy of

Motion Picture Arts and Sciences--at a time when the controversy over whether

Mercedes McCambridge deserved credit for her contributions to Linda Blair's

voice as the devil coming out...

GROSS: In "The Exorcist."

Mr. JONES: Yeah, in "The Exorcist." And I thought that was a silly argument;

that I said to myself, all Mercedes is is special effects. And I wanted to

keep that clear in my case, so I didn't even take credit for the voice of

Darth Vader.

GROSS: Forgive me. I know it's a small part of your career, but I have to

ask you about the CNN voice. The first time someone said to me, `You know, I

think that's James Earl Jones,' I said, `Nah,' you know. ...(Unintelligible).

Of course, everybody knows this now, that you do the voice of CNN. Why did

you decide to take that on when you were offered it?

Mr. JONES: Oh, you asked me what has the "Star Wars" involvement meant to

me. What it did, it made my voice--What do you call it?--viable in the

commercial world. But I don't know why really I avoided that great way to

make a living and great craft unto itself. But the "Star Wars" sort of put my

name on the A list, as they say out there, for authoritative voices.

GROSS: So your attitude was, `Why not take advantage of it.'

Mr. JONES: My attitude, yeah. Oh, exactly. Yeah. I mean, why kick

something that's going to sit on your lap out of the house. I think the first

commercials I did--I did one for Chrysler and one for Goodyear and one for

Fisher audio products, and they asked me to just give us the sound of God.

Goodyear Vector tires, you know. Let God sell Goodyear Vector tires.

GROSS: No problem.

Mr. JONES: They were not embarrassed about saying that.

GROSS: So do you have a voice of yours that you think of the voice of God?

Mr. JONES: No, no. It just--the sound is--let it go as bass as it can go and

still be clear.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. JONES: And to sound like I mean it. There's not a product I've ever

promoted that I don't use, including Wells Lamont gloves, working man's

gloves.

GROSS: And, of course, the Yellow Pages.

Mr. JONES: And Reuben's dinners out in--Rueben's chain of restaurants. Orson

Welles and Vincent Price and I were once asked to simply, on a recording, read

the menu with as much slobbering, lustful sounds as we could conjure. And we

got paid for it.

GROSS: One quick, very quick last question. Have you ever been in a kind of

difficult situation, either on the verge of being mugged or given a traffic

ticket that you didn't want to pay or something where you used your big,

authoritative voice to intimidate the other person?

Mr. JONES: The last time I was mugged it was multiple muggings because my

(unintelligible) St. Louis, Missouri, at the age of 14. I was mugged several

times one afternoon before I figured it out, what was going on. And in those

days, you didn't always get killed when you got mugged.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. JONES: You got surrounded by a bunch of kids who said, `Give me your

money.' I said OK. Being a farm kid, why would you fight over some movie

change? The idea of fighting didn't occur to me, so therefore I was quite

safe. The only time I've used the voice, though, in my adult life was when I

got my first CB radio and I used the Darth Vader as my handle and panicked a

few people on a cross-country drive from New York to Los Angeles and I've not

done it since.

BIANCULLI: James Earl Jones speaking to Terry Gross in 1993. He'll provide

the voice of Darth Vader again in next year's "Star Wars: Episode III:

Revenge of the Sith," the final entry in the George Lucas space epic. And you

can hear James Earl Jones as Darth Vader now in the just-released DVD box set

of the first "Star Wars Trilogy."

Coming up, a review of the film "The Motorcycle Diaries." This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: New movie "The Motorcycle Diaries"

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

"The Motorcycle Diaries" stars Gael Garcia Bernal, the young Mexican actor

from "Y Tu Mama Tambien," as the young Ernesto Guevara, before he became the

guerrilla leader known as Che. The film is based partly on Che's diaries,

which recount his momentous and consciousness-raising 8,000-mile journey

across South America as a 23-year-old medical student. Film critic David

Edelstein has a review.

DAVID EDELSTEIN reporting:

Robert Redford has done many heroic things for the independent film movement,

but as a filmmaker, his name stands for the blandest kind of humanism, liberal

and thrust, but that thrust could hardly dent a marshmallow. He's the

executive producer of "The Motorcycle Diaries" and here he is on why he picked

the Brazilian filmmaker Walter Salles to direct. `I knew that Walter would

handle the story with lyricism and humanity,' he said, `rather than focusing

on the politics of who Ernesto would later become.'

The movie Salles made, from a script by Jose Rivera, is so awesomely beautiful

to look at, you want to sink to your knees. Salles and his friend,

cinematographer Eric Gautier, retrace much of the 1952 journey of Guevara and

his amigo Alberto Granado. Che, a medical student, is 23; Alberto, a

biochemist, 29. They're upper middle-class young men with a starry-eyed

notion of traversing South America on Alberto's ramshackle 13-year-old

motorcycle, which they nickname The Mighty One and which predictably sputters

to a halt at regular intervals. They travel from Argentina to Chile and into

the mountains of Peru, and these aren't picture postcard images. The camera

is both restless and contemplative. The cinematography somehow imbues the

landscape with the onlooker's thrill and spiritual hunger. You can almost

touch the huge clouds passing over the dark mountains and feel the icy

sharpness of the deep blue rivers.

"The Motorcycle Diaries" is transporting. And, yes, it's so lyrical that you

almost don't notice how stiff and programmatic it is and how undramatized.

The working poor shuffle on, photographed in the Walker Evans manner. And

excerpts from Che's actual diary inform us that their faces are tragic and

haunting and that time with them on a cold night makes him feel closer to the

human race.

In the supernally green Peruvian mountains, Che and Alberto come upon the

ruins of an Incan civilization, wiped out by the capitalist Spanish

conquerors. `How can we feel nostalgia for a civilization we never knew,'

wonders Che in voiceover. By now the friends are ennobled, although they try

to scam free lodging by posing as leprosy experts, they're soon doing actual

good works in a leper colony, defying the nuns, who insist on a strict

distance between caregiver and patient. His moment of epiphany is when the

asthmatic Che swims across a dangerous channel at night to share his 24th

birthday with the disenfranchised lepers. It's a rousing finish. Not for

nothing did the film win a much reported standing ovation at the Sundance Film

Festival.

The director uses Gael Garcia Bernal as an object of frail beauty. He has

pillowy lips like Julia Roberts and a soft demeanor, his dreamy eyes fixed on

the horizon. He's a picture-perfect budding martyr but he hasn't been filled

in. Salles reportedly trimmed scenes of Che sharing a prostitute with Alberto

and having sex with a leper. This gorgeous movie is generic and sexless.

More important, it's incomplete.

Michael Almereyda, who did the modern "Hamlet" with Ethan Hawke, had a Che

script I read a few years ago. It was a romantic portrait too, of the same

period, but it ended not with Che bidding a tender farewell to Alberto but

with his decision to embrace violence and his first guerrilla kill. That

strikes me as a more honest and gutsy way to connect the dots. It wasn't

Che's awareness of historic injustice against the working class and the

indigenous peoples of both American continents that made him one of the most

galvanic figures of the 20th century. It was how he used that awareness to

transform himself into a romantic symbol of righteous violence, violence that

led to the overthrow of corrupt and murderous governments but also to wanton

executions and prison camps.

Turning the birth of Che the revolutionary into a story of lyricism and

humanity is to throw out the most fascinating and unique part of the story and

turn politics into middle-brow art movie myth.

BIANCULLI: David Edelstein is the film critic for the online magazine Slate.

(Credits)

BIANCULLI: For Terry Gross, I'm David Bianculli.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.