Other segments from the episode on October 22, 2008

Transcript

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20081022

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-1:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Steve Martin On Being 'Born Standing Up'

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is Fresh Air. I'm Terry Gross

(Soundbite of album "Let's Get Small")

Mr. STEVE MARTIN (Comedian, Actor): To open the show, I always like to do one thing that is impossible. So right now, I'm going to suck this piano into my lungs.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: That's Steve Martin from his 1977 album, "Let's Get Small." He did standup comedy for 18 years. His memoir, "Born Standing Up," looks back on those years, what was going on in his mind and on stage. It just came out in paperback.

Steve Martin became famous from his appearances on "Saturday Night Live" in the '70s, where he was one of the wild and crazy guys. As we'll hear, the fame that brought him huge audiences also eventually made it impossible for him to do the kind of comedy that made him original. Martin is still making movies and in recent years has also written plays, essays, and books. He won the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor in 2005 and was one of the Kennedy Center honorees last year. Steve Martin, welcome back to Fresh Air. I love your new book.

Mr. MARTIN: Great to be here. Thank you. Thank you very much.

GROSS: I'd like you to open with a reading from the beginning of the book, and we've edited this slightly to make it just a little shorter for the broadcast.

Mr. MARTIN: Great. I'd be happy to.

(Reading) I did stand-up comedy for 18 years. 10 of those years were spent learning. Four years were spent refining, and four years were spent in wild success. I was seeking comic originality, and fame fell on me as a by-product. The course was more plodding than heroic. I did not strive valiantly against doubters, but took incremental steps studded with a few intuitive leaps. I was not naturally talented. I didn't sing, dance, or act, though working around that minor detail made me inventive.

I was not self-destructive, though I almost destroyed myself. In the end, I turned away from stand-up with a tired swivel of my head and never looked back until now. A few years ago, I began researching and recalling the details of this crucial part of my professional life, which inevitably touches upon my personal life and was reminded why I did stand-up and why I walked away.

In a sense, this book is not an autobiography but a biography because I am writing about someone I used to know. Yes, these events are true, yet sometimes, they seemed to have happened to someone else, and I often felt like a curious onlooker or someone trying to remember a dream. I ignored my stand-up career for 25 years, but now, having finished this memoir, I view this time with surprising warmth. One can have, it turns out, an affection for the war years.

GROSS: Thanks for reading that. That's Steve Martin reading from his memoir "Born Standing Up," which has just been published in paperback. You know, I guess I didn't realize how much you'd closed the door on your comedy years, how much there was like a before and after. It ended. You were done, and that was it.

Mr. MARTIN: Right. I - it was about 1981. I still had a few obligations left, but I knew that I could not continue, but I guess I could have continued if I had nothing to go to. But I did have something to go to, which was movies. And, you know, the act had become so known that, in order to go back, I would have had to create an entirely new show, and I wasn't up to it, especially when the opportunity for movies and writing movies came around.

GROSS: Why would you have had to create an entirely new show?

Mr. MARTIN: Like I say, the act was really - there was a passage in the book which I cut because it was so hard to explain. But the act, essentially, besides all the jokes and bits and everything, was conceptual, and once the concept was understood, there was nothing more to develop. It's like painting the same blank canvass over and over and over and over and over. Once the concept is known, you don't see - need to see two. And that was in the back of my head, that I was really done artistically with what I had created or pastiched.

GROSS: You know, in the reading that you just did, you described yourself as not being naturally talented. Did you think of yourself as naturally funny?

Mr. MARTIN: I didn't think of myself in that way, no, although I just loved comedy. I was raised with Laurel and Hardy and "I Love Lucy" and Jerry Lewis, and I just loved it. And I had a friend in high school, and we will just laugh all day and put on skits and, you know, it's the Andy Kaufman thing or the Marty Short thing, where you're performing in your bedroom for yourself.

And I loved magic, and so I would practice my magic tricks in front of a mirror for hours and hours and hours because I was told that you must practice. You must practice, and never present a trick before it's ready and - but I was just inclined towards show business, but I didn't know what. I just liked being on stage.

GROSS: Now, you got your start working in Disneyland. You were living in Southern California, and you, when you were 10, you were selling guide books there. Then you later worked for a magic shop demonstrating magic tricks. And I get the sense from your memoir that demonstrating those magic tricks, you know, hours a day and really getting them down because you were doing them so much that that gave you a sense that performance required a great deal of craft. That even comedy wasn't just a question of going out on stage and saying funny things, that there was enormous amounts of work and practice and thought that would have to go into it?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, that idea that you really had to work at this stuff didn't necessarily come from Disneyland. It - I mean, yes, in terms of presenting a trick, but having it so well-honed in your mind was really giving me a sense of security. It was, I don't want to go out there half baked, and, you know, you'd learn that through the years.

You know, you do a magic show with a friend, and you rehearse it a couple of times, and, yes, every - all the timing has to be exactly perfect, but while you're out there, it's a different world. It's not your mirror. You have to make on-the-spot adjustments, but that's just, you know, whatever your entertainer does.

But actually, working at the magic shop really gave me a sense of comedy because it was all jokes. We did the tricks, but we had all these jokes. I had a friend, Jim Barlow(ph). You know, he was the guy I worked with there, but he had patter worked out, you know. He would go up to customers and say, may I take you money - I mean, help you? And, you know, call them suckers, and it was really funny and kind of friendly rude.

GROSS: What was your patter?

Mr. MARTIN: Oh, I just took all of Jim's patter. I'm trying to think of other ones. Oh yeah, I'd say - somebody would buy something and would say, and because you are our 100th customer today, you get a free paper bag. You know, it's little silly things like that, but I am at Disneyland and 15.

GROSS: Right. But your early act was a combination of banjo playing, juggling, magic tricks, and comedy, and some of that stayed in your later act, too, but it sounds like a Vaudeville act.

Mr. MARTIN: Yes. I was very interested in Vaudeville. It was the only sort of discipline that was a five-minute act on stage, which is what I really enjoyed and saw myself doing. And I bought books on it. I went to the Long Beach Pike, which was a carnival fair, you know for - it's really a place for drunken sailors to get tattoos. But there was also side shows. I was very interested in that. You know, there was these - oh, and there were these short acts.

There was one of the employees at Disneyland that I worked with who was named Dave Stuart, and he worked in Vaudeville. And he did his act for me one day on the floor of the magic shop, and I - he had a couple of great gags. One was - that I actually used, and I asked him if I could use them because I was very strict about using any material that wasn't mine or that was taken from somebody else. Well, let's put it this way, I became strict. I wasn't strict at first.

There was one trick that - one joke that Dave Stuart did where he said and now - he had a glove, white glove in his hands, a magician's glove, and he said, and now, the glove into dove trick, and he threw it into the air, and then it hit the floor, and he just looked at it and, you know, said, for my next trick, and he went on. And it was the first time I saw comedy created out of nothing, of nothing happening. And I glommed on to that.

GROSS: What you were doing, I think, is not only making comedy out of nothing, but making comedy out of people's expectations, which you were going to fail to fulfill.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, yes, exactly. And I really started that when I became a semi-professional, meaning I was working the local folk music clubs, going around either working for free or for a week. And I quickly decided that, you know, the material was, you know, good or weak or whatever, but I decided, whatever it was, I was going to pretend like it was fantastic and how great am I, how great is what you're seeing. And I think that's what the audience tuned into because they couldn't believe that someone actually was that confident.

GROSS: With such weird, you know, like, bad material because some of the material was, like, consciously not funny.

Mr. MARTIN: Right. Well, I had one bit that I opened with. I'd say, and now, I would like to do the nose on microphone routine. And I would lean and then put my nose on the microphone and then stand and, you know, hold my arms out, like tada! And the laugh came, not then, but when I said, and next. You know, because nothing had happened and, you know, I found that you could laugh at something that happened 30 seconds ago now, only because you change a subject.

And at one point in my show - these are the local folk clubs around Orange County - I had trouble figuring out how to end, so I just dragged the ending out walking through the audience saying goodnight. It was so great. Thank you so much. I have to leave. I'm sorry. I have to leave. I have to beg off, and it went on for, you know, five minutes. And eventually, I could never end it, and I ended up taking the audience out into the street and walking around with them.

GROSS: Well, you tell the whole genesis of that. I mean, it started off, you are performing in a class in Vanderbilt University. Go ahead.

Mr. MARTIN: Yes. Vanderbilt University and, you know, you perform in all kinds of odd performing situations. It's either, you might be outdoors, indoors, on a riser, no riser. But this was at one of these college theaters for - it wasn't an actual theater. It was a practice theater, so it had a stage, but it had no wings. And - or it had little small wings, but there was no exit from the wings. You had to exit through the class.

And so, they - we did the show in this classroom, and I ended. And I said, you know, whatever I did the end. I mean, this - I was just as just when I was, you know, I don't remember how my act ended, but I ended, and I went off, and the audience just sat there. There's no way out for me except to go through the audience. So I actually went out, and I said, it's over. It's actually over.

And they still sat there, and I packed all my stuff, and then I thought, well, they're just not leaving. So I went - this was the first time I ever did this. I went through the audience, and I just started talking, I have no idea what I was saying, just talking. And then, they followed me out into the hallway. And, you know, I had little repertoire of lines, some things that I was saying, and then we ended up outside. And there's like 200 people and me. And I came across an empty swimming pool. It was drained. And I said, everybody get into the pool, and so they all got into the pool. And I said, now, I'm going to swim over the top of you, and they all, you know, stiff armed to me over their heads. But anyway, you can imagine it was a, you know, kind of a wild night, at least for then, this would be the early '70s. But I went home that night, and I thought, oh, something happened. That was good.

GROSS: I think one of the things that must have made this so funny in its time was that people probably had no idea what you were doing or how to take you or what would happen next.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, that is - yeah.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, that is true because, like I say, when I quit, the act had become known, and when I - but now, it was unknown and so everything - it was one of my decisions, actually, or a crucial decision of my performing life. When I was in college, you know, I had an act that was a pastiche of gags from books and magic tricks and a few original things.

And I realized everything had to be new, that the audience had to feel like they were seeing something they had never seen before. And I had to X out three quarters of my act and start over. And so, at this time, the audience was seeing something, at least for those times, new. And as the years went on, it became un-new. I said, you know, you can only be new once. And you have that thrill presenting something different or dramatic, you know, once only.

GROSS: My guest is Steve Martin, his memoir, "Born Standing Up," has just come out in paperback. We'll talk more after a break. This is Fresh Air.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Let's get back to our interview with Steve Martin. His memoir, "Born Standing Up," has just been published in paperback. It's about his 18 years as a standup comic. This is - I think must have been around '68 or '67, you had a really bad experience. You were going to see "The Producers," the Mel Brooks movie.

Mr. MARTIN: Oh right.

GROSS: Yeah. And you got high, smoked marijuana beforehand, and had a panic attack in the theater but didn't know what a panic attack was. So had no idea what it was that you were experiencing. What were you experiencing that was so terrifying in that movie theater?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, I just got my job on the Smothers Brothers. And, you know, pot was a daily ritual, never at work, you know, at night or something. And I was a cowardly drug taker, but actually, I view this as a positive experience, even though it was horrifying. It was an anxiety attack, and for those who have them or had them - I don't get them anymore, thank God, but it's a terrifying experience of disassociation from your own self. And it's a morbid sense of doom. And you feel like you're dying.

But what it did was it kept me from drugs going into the late '60s and early '70s because I never - I couldn't take Aspirin, I was so afraid of this event happening again, which it did for several years, and then it finally calmed down. But it kept me from, as I said in the book, the scourge of cocaine, which was common, and I never took LSD. I never took anything after that.

GROSS: When you had that first anxiety attack after smoking marijuana, did you ask yourself, is it the marijuana that's transforming me and creating a false feeling in me of this panic, or is the marijuana bringing something that is genuinely me that's just been hidden from my sight, and marijuana's bringing out this like really larger truth about who I am and what the world is.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, I believe the latter that - first, I believe, for some people, they can smoke marijuana and have no bad physical reaction, but I noticed that, you know, in the first two months of smoking marijuana, it's fantastic. It's the greatest thing in the world. You're laughing. You know, I could play the banjo for hours and hours and hours and practice the banjo and get into music. It's very good for the senses.

But eventually, for me and other people I've talked to, it produces paranoia, and I don't mean - paranoia was a big word then, and people kind of intended it to be about the police - oh, we're going to get busted. I believe the word was subconsciously being used because people were becoming paranoid, meaning that they're a little out of touch with the world around them and feeling that there's something going on that I'm not in on. And it got so severe with me, and I believed that it was actually happening, this kind of paranoia that people didn't like me, and that they were whispering, you know, really looking back, kind of extreme, but it was only related to marijuana.

And then, it led into this state of anxiety which could come over me then - but I never smoked pot again, but I would still get these anxiety attacks for several years until I finally understood them. And that was a big moment, when I did research on it and found out what they were because, for some reason, no doctor told me what it was. That it was harmless, essentially, because I thought it was damaging me every time it would happen. But I believe it was a nervousness created from my new job at the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. 21 years old, I stumbled into this next level of show business, and I was insecure, but I could not afford to be insecure. And so I had buried that insecurity, and, of course, it came out physically.

GROSS: It's kind of interesting in a way that you were doing this comedy that was so associated with getting high, and your humor was so kind of keyed in to the experience of being high in a way and some of the absurdity that you might experience with that. Yeah. And yet...

Mr. MARTIN: I have to contradict you because my material was not anything to do with - I have maybe one or two...

GROSS: No, I don't mean literally. But the sense of, like, absurdity or non-sequitur, that certain things didn't make sense, that certain things were absurd, was very compatible.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah, I guess so. Right. And people would accuse me - after I got off stage, that would say, you're so stoned up there.

GROSS: Right. And yet, you are the person who's going to be totally staying away from drugs.

Mr. MARTIN: I'm the last person you're going to see stoned.

GROSS: Steve Martin will be back in the second half of the show. His memoir "Born Standing Up" has just been published in paperback. I'm Terry Gross, and this is Fresh Air.

(Soundbite of comedy performance)

Mr. MARTIN: Thank you.

(Soundbite of applause)

(Soundbite of banjo music)

Mr. MARTIN: Hey, this guy is good.

(Soundbite of applause)

(Soundbite of banjo music)

Mr. MARTIN: I'm a rambling guy.

(Soundbite of applause)

Mr. MARTIN: Well I'm rambling, rambling around. I'm a rambling guy.

(Soundbite of applause)

(Soundbite of banjo music)

Mr. MARTIN: I ramble around. Oh, yes, oh, yes, oh, yes, oh, yes, oh, yes, oh, yes, oh, yes, oh, yes. Oh, no.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARTIN: I'm a rambling guy. Hey, R-A-M-B-L-Y-N.

(Soundbite of banjo playing)

Mr. MARTIN: I ramble out to San Francisco and the car get Odello. Oh yes, oh yes, oh yes, oh yes, oh yes, oh yes, oh yes, oh yes, oh no. Hey, rambling. Apostrophe, a rambling. OK, everybody. Come one, sing with me. A rambling guy.

What's the matter, you people uptight or something? OK, ladies only. He's a rambling guy, oh no. OK, I'm in, rambling, rambling, rambling. OK, this side of the room. OK, other side. Beautiful. There's two pieces in the room. Now, there's three. OK. Two sevens spice up, it's OK. In Chinese now. (unintelligible)...

(Soundbite of banjo music)

GROSS: This is Fresh Air. I'm Terry Gross back with Steve Martin. We're talking about his years as a comic and why he walked away from stand up after 18 years. His memoir "Born Standing Up" has just been published in paperback.

On your first album, "Let's Get Small," you do a bit about the spotlight. And before we actually hear the recoding of it, I want you to tell us about the first time you did it.

Mr. MARTIN: Oh, I just had this - when I worked at Disneyland, I worked with a woman named Irene who was from Biloxi, Mississippi - Missouri - Mississippi. And she had an expression that she used all the time. She'd say, well, excuse me for living. It was just kind of funny. And it always stuck in my head, so I thought, I think I could use something - do something with that.

And so I told the spotlight operator, I said, whatever I say, do not change the spot. I'm going to ask you to change the spotlight to blue. Do not change it to blue. I had a friend that night up in the - next to the booth, John McEwan, whom I still work with, we're recording a banjo album, as a matter a fact. And I started telling the spotlight operator to change the spot. And...

GROSS: This is on stage you're telling him this?

Mr. MARTIN: On stage, I started telling him.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. MARTIN: And at one point - this is the first time I ever did it on stage. And at one point, he was so convinced that I'm - was sincere. he started to reached to change it, and John said. no, don't. I don't think he wants you - anyway. So this is the bit.

GROSS: OK. So let's hear it. So this is the spotlight bit, and this is Steve Martin, and he has a new memoir...

Mr. MARTIN: I don't stand behind any of these routines 40 years later, but go ahead.

GROSS: So here's Steve Martin.

(Soundbite of "Let's Get Small")

Mr. MARTIN: Can I have a little mood lighting on this, please. I'd like to do a thing now that's kind of a departure for me, It's kind of more into this - it's mood lighting, like blue spot or something. Hello?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARTIN: Nobody back there? That's OK. Thought there might be somebody back there. OK, I guess, I figured, closing night, you know, that that does not make any...

(Soundbite of beep)

Mr. MARTIN: Difference.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARTIN: Kind of pissed off about this because we've been going on all week, and I'd think, by now, we'd have it under control. But I don't know, it's - you see, this club has been in business about five or six years. First, actually, the Troubadour at first, and then it became the Boarding House. And then, you know, they still have a lot of a hippies working here. And...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARTIN: And I can understand the drug thing, you know. So they feel that it's more important to take the drugs than to do a good show for...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARTIN: You know, I'm really up to hear with this - it's just a matter that I am on stage, and it's my ass out here, you know what I mean? And I come out, and I'm giving, and I'm giving, and I'm giving, and I keep giving, and I give some more, and I make a simple request. I say, hey, could I possibly have a blue spot? But I guess the lighting crew feels they know a little bit more about show business than I do.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARTIN: Although I've been in the business a few years. And I think I know what works best. I'm sorry. But I am angry. I come out here, and I can't get a little cooperation from the backstage crew. Excuse me.

(Soundbite of clapping)

GROSS: That's Steve Martin from his first album, "Let's Get Small." Now, people seem to be with you throughout this. Were they already hip to what you were doing?

Mr. MARTIN: They were in San Francisco because that was a home base for me. And I was really stupid in that. It took me awhile to figure out, oh, this act doesn't work everywhere. I was just reading in the book, before we started the passage about the Hub Pub Club in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, which was a members only, bring-your-own-booze, you know, club that, I just died. I just died so badly, and I was just rereading it.

I remember one night, I was on stage getting no laughs, and a guy said to his date, I don't get any of this, really loud. And I heard it. The whole audience heard it. It actually made me laugh because I didn't either. At that time, I was - it was going so badly. But then I would go to San Francisco, and where the audience was younger and more with it and more stoned, and it would go great. It took me so long to figure out, oh, it's a different type of audience. I shouldn't be playing these other places. They're a soul killing to me. So the Boarding House and the Troubadour in L.A. were very good and the Ice House and different clubs around the country.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Steve Martin, and he's written a memoir about his years as a standup comic. And it's called "More and Standing Up." It's just been published in paperback. Let's take a short break here, and then we'll talk some more. This is Fresh Air.

(Soundbite of banjo music)

GROSS: My guest is Steve Martin, and he's written a memoir about his years as a standup comic before he started making movies, and it's called "Born Standing Up." It's just come out in paperback. We were talking about the kind of comedy that you started doing that was, I think, maybe closer to performance art than stand-up in some ways.

Mr. MARTIN: In some ways, yes. You know, I was kind of controversial. And I remember a writer name Emily Krieger wrote, I like Steve Martin because he brought surrealism to the masses. So I guess, it was - it walked the line between. You know, I was always an entertainer first. I knew things had to work. It was just a new way to get them to work. But, you know, silence was not pleasant. And my confidence didn't override silence from the audience.

GROSS: When you started in comedy, it was before the comedy club era.

Mr. MARTIN: Yes.

GROSS: So you couldn't play the comedy clubs - there weren't any. But there are a lot of - like folk music clubs. Did the fact that you had the banjo in the act give clubs the opportunity or the excuse to hire you, even though you weren't a conventional musician?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, looking back, I never thought of that, but I think they - the clubs would hire comedians. They were always the opening act, unless they were big names. But, you know, I put the banjo in, I put the magic in to fill time because I didn't have enough comedy material, and all that just stayed.

And looking back, I remember when I was playing a club in Los Angeles called Leadbetter's. There are some very funny people who were working the clubs, too. They weren't comedians. They were in folk groups, but they were just funny. Then I did my act, and I always closed with a magic section, like five minute magic, a little mini magic show. And my friend came up and said, I got a line for you. I said, what? And he says, oh, I know what you're thinking. This is just another banjo magic act.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARTIN: And, you know, I never thought of it that way, but looking back, I thought, what was the banjo doing there? I like to play the banjo, and it - like I say, it filled time, and I could get - eventually, I worked out bits with it. I love doing my surreal sing along that had words that no one could follow.

GROSS: Well, let's play an example of that. And this is the one, be courteous, kind, and forgiving. Before we here it, tell us about writing it. Yeah.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, there's absolutely. As much as I remember, I just thought, I want to sing a song that starts normal and ends crazy, and that's all that was.

GROSS: Not only starts normal. It starts so kind of like aphorism. It's just like...

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah, it's tender. It starts tender.

GROSS: Tender and aphoristic, and then it gets, it gets nuts. But let's hear it because you recorded this on your first album. So this is Steve Martin from his first recording, "Let's Get Small."

(Soundbite of album "Let's Get Small')

Mr. MARTIN: You know, folks, when I was a kid, I was very close to my grandmother. And she used to sing a song to me when I was just so high, and it's always meant something to me. I'd like to do it for you right because it does have meaning in today's world. Even all these years, you know, this - even during the hip drug days, you know, when everybody is listening so cool and everything has double meaning, it's a little simple tune, would keep coming back to me. I think it kind of guided me through those years.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARTIN: I'd like to do the song for you right now. I think it might have a little meaning for you.

(Soundbite of banjo music)

Mr. MARTIN: (Singing) Be courteous, kind and forgiving.

Be gentle and peaceful each day.

Be warm and human and grateful,

And have a good thing to say.

Be thoughtful and trustful and childlike.

Be witty and happy and wise.

Be honest and love all your neighbors.

Be it inseqitious (ph), purple, and clairvoyant.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARTIN: (Singing) Be pompous, obese, and eat cactus.

Be dull and boring and omnipresent.

Criticize things you don't know about.

Be oblong and have your knees removed.

Be tasteless, rude, and offensive.

Live in a swamp and be three-dimensional.

Put a live chicken in your underwear.

Get all excited and go to yawning festival.

OK, everybody.

GROSS: That's Steve Martin from his first album "Let's Get Small." He's written a memoir about his days as a standup comic, and that's called "Born Standing Up." It's just been published in paperback.

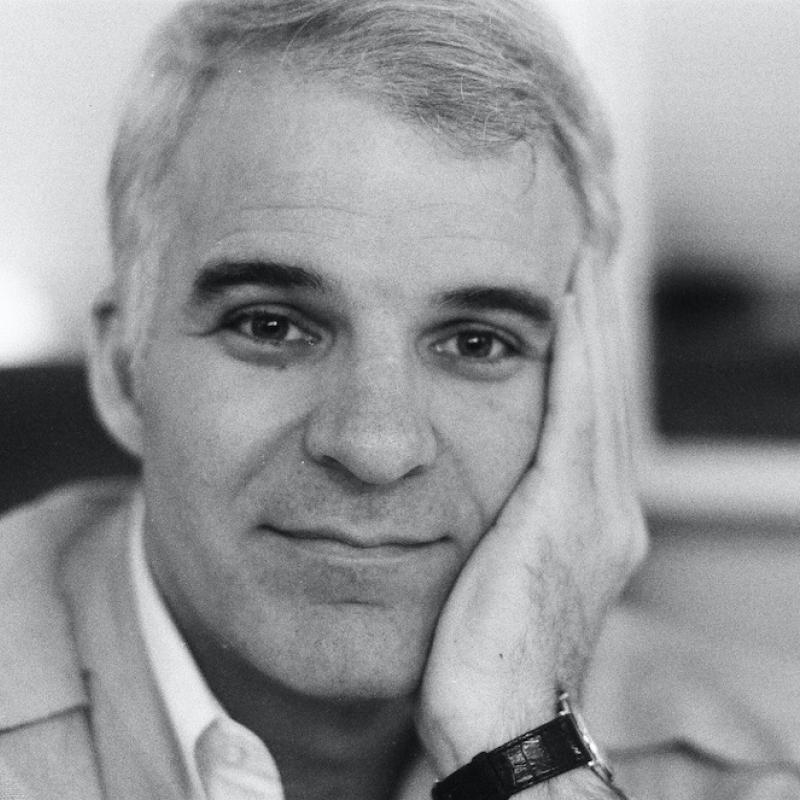

There's a terrific photo. There's a bunch of photos in your memoir. My favorite is the one where you're standing with - holding your banjo, and your hair is really kind of long and scruffy. You have a beard. You're wearing a shirt with a big collar that's open, and you have, like, a necklace of shells that you're wearing.

Mr. MARTIN: Squa - you know, it's a squash blossom turquoise necklace, which was very...

GROSS: Oh, I'm sorry, excuse me.

Mr. MARTIN: Popular at the time. Yeah.

GROSS: OK.

Mr. MARTIN: Indian jewelry was very big.

GROSS: And your belt is filled with that, too.

Mr. MARTIN: It's a Conch belt. It's made from, you know, it's made by Navajos, I believe.

GROSS: OK. And...

Mr. MARTIN: And by the way, my shirt, I'm looking at the photo right now. My shirt was hand embroidered by a momentary girlfriend. It was all very - it was hippy. It was just hippy. And that's what - I look at this photo, and I'm trying to be somebody else here.

GROSS: Yeah, who?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARTIN: Try to fit out. Somebody said, oh, you look like you're trying to be the Eagles.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Well, the caption underneath is no comment.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah.

GROSS: But at some point, you decided to cut your hair, shave the beard, and wear a suit on stage.

Mr. MARTIN: Yes. That was another...

GROSS: How did - yeah, go ahead.

Mr. MARTIN: It was another crucial, I mean, it sounds so frivolous now, but it was a crucial decision then. I - you know, the Vietnam War was raging, but it was winding down. The - America was very politically conscious. There were protests. There was political humor everywhere. And I just sensed that the era was ending, that it was kind of - I don't like this word - an implosion because you can't just keep taking drugs and have a philosophy live on.

People are dying, and Charles Manson came on the scene and besmirched everyone with long hair. And so, I decided, OK, I'm putting on a suit, I'm putting on a tie, and I'm cutting my hair. And, as I say in the book, rather than being at the tail end of an era, I was at the beginning of a new one. So I had kind of poised myself to announce, OK - and also, and I cut every political reference out of my act, which was a staple for comedians at the time because it was such an easy laugh. You just mention the word Nixon, that's something everybody would cheer. I mean, meaning - because they didn't like him. And so that was, at that point, the difference between me and them.

GROSS: Well, I love it how describe in the book you. You write, after you put on the suit and cut your hair, instead of looking another freak with a crazy act, I now look like a visitor from the straight world who had gone seriously awry.

Mr. MARTIN: Right.

GROSS: So, did you feel like you had kindred spirits in the performance world when you were getting started, who had a more like conceptual or avant-garde approach to what they were doing? Like...

Mr. MARTIN: Well, I'm trying to think. I just respected comedians, whether they were or they weren't from new or old - about Bob Newhart, I loved, and George Carlin was hilarious at the time and Bill Cosby and Richard Pryor. And there was a comedy magician who's still alive, Carl Valentine (ph), who did an act of all magic tricks that didn't work. And it was, still is, one of the funniest things I've ever seen.

And of course, there was influence there, too, because he was already doing it, and I took that concept. I don't know if I took it from him, but I took that concept into gags and comedy routines. But talk about kindred spirits, I thought I was alone. And that was uplifting. I thought, I'm the only one doing this, and then I saw "Saturday Night Live," and I thought, oh, oh no. There's somebody else doing it.

GROSS: Good thing how that worked out for you. I mean, you found your people there and your audience and fellow comics who were on the same wavelength.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, yeah, right, and I was so fortunate to have been invited into that group, too. Because now, we were all one. They were on a roll. I was lucky to be accepted. Lorne Michaels had been a long-time friend, but I went in there, and then, my career exploded.

GROSS: I love the review that your father wrote of your first "Saturday Night Live" appearance, and this is in his news column in the newsletter for the Newport Beach Association of Realtors. He was the president of the association. And you want to quote the line, or should I read it?

Mr. MARTIN: You can go ahead, and I'll comment on that.

GROSS: He wrote, his performance did nothing to further his career.

Mr. MARTIN: Right.

GROSS: Of course, nothing could be further than the truth. But did that - like, what was your reaction when your father gave you a bad review?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, first, he felt terrible about it later.

GROSS: Well, he couldn't figure out beforehand that that was a bad thing to do?

Mr. MARTIN: That was my father. But he always thought he had to speak the truth. But, when I was a kid, and I would listen to, let's say Little Richard, and I'd listen to Little Richard and say, God, he's great but - and I'd see photos of him and everything, and I'd think, what does his mother think when he's singing, wop-babalu-bop-doo-wop-bam-boom? Is his mother proud or embarrassed?

Well, I think my father, he couldn't quite be proud of an unconventional show biz act that he didn't quite understand. And I think he was kind of embarrassed by it among his friends. And I think this was a misguided effort to say to his friends, look, I know it's not very good. By that time, I had been so kind of alienated from my father that these negative comments and reviews were actually my encouragement.

Like, I talk a moment in the book about being - I was a writer for "The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour," and I was going to - I had moved on to "Sonny & Cher," and I decided, I'm going to quit this because it's keeping me from my performing career. I am going to go on the road. And I went to an agent in Hollywood, my agent, my writing agent. I said, I'm going to do this. He said, stick to writing. But I didn't take it as an insult or discouragement. I took it as encouragement because I saw it as, oh, this is that classic show biz moment when you say, Jolie, you're never going to be a singer.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: It's good you'd seen all those movies.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah. Yeah.

GROSS: So, was it hard for you to change your image from, like, the wild and crazy guy of the stand-up years when you decided to give up stand-up and divert your life to - professionally to movies?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, it took a long time, but I did know this - that one day, it will be forgotten. And so I just did what I was going to do, and there was this hangover effect of wild and crazy guy, wild and crazy guy. And now, it's a dim memory, and I was able to transition into whatever it is I'm - you know, I'd say three different transitions I've been in my professional life. And it was actually with the film "Roxanne" that I wrote and performed in, and I sensed something new. Before, there was kind of celebrity - it's not worship, but the celebrity effect. But I sensed something new with that movie, which was respect.

GROSS: That was your, like, Cyrano de Bergerac film.

Mr. MARTIN: Yes. Exactly. Oh, I like this better.

GROSS: It has been so great to talk with you. I really want to thank you a lot.

Mr. MARTIN: Thank you very much. It's really fun to talk about myself.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Thank you, Steve Martin.

Mr. MARTIN: OK. Thank you.

GROSS: Steve Martin's memoir, "Born Standing Up," has just been published in paperback. This is Fresh Air.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

95973456

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20081022

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-1:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Taking Measure Of 'Dear Science'

TERRY GROSS, host:

With just three albums, the quintet TV On The Radio has established itself as one of rock's most experimental yet accessible bands, mixing provocative lyrics with everything from punk rock to hip hop. Rock critic Ken Tucker says TV On The Radio's new record, "Dear Science," is an eclectic, purposeful album

(Soundbite of song "Halfway Home")

TV ON THE RADIO: (Singing) The lazy way they turn your head into a rest stop for the dead,

and end it all in gold and blue and gray.

KEN TUCKER: The most interesting pop music being made right now is mongrel stuff, collage works, compositions capacious enough to take in elements of not nearly prevailing trends but the whole of pop and rock history. It is at this sort of musical patchwork that TV On The Radio excels. They are expert craftsmen in the sense that they can take a funk guitar rift, a soul music falsetto, and a disco drum rhythm and turn it into a call to cultural arms. I have just described this song called "Crying."

(Soundbite of song "Crying")

TV ON THE RADIO: (Singing) Laugh in the face of death under masthead.

Hold your breath through late breaking disasters.

Next to news of the trite.

Codes and the feelings that meant to be noble like coke in the nose of the nobles.

Keeps it alight.

And the wrath and the riots and the races on fire,

And the music for tanks with no red lights in sight.

Got you crying, crying, oh crying.

Oh crying, oh my myâ¦

TUCKER: "Crying" is all the more impressive for the tension it creates between its music and its lyric. The jaunty dance funk ramming up against what even the band itself calls a heavy scenario of riots, righteous wrath, and, quote, "the races on fire." That last phrase about race carries some weight in this context. Four of the five members of TV On The Radio are African American, with lead singer Tunde Adebimpe, like Barack Obama, an American of African parentage.

The rock critic press term for non-R&B music made by blacks is post-racial. But TV On The Radio is more complex and smarter than that fast old label. They've seen of strife both specific and general, opening up America's problems with black suffering and oppression to either triumph over it, well against it, or as is the right of any good artist, to ignore it as the mood suits them.

(Soundbite of song "Golden Age")

TV ON THE RADIO: (Singing) Heart beat sounding ricocheting in their cage.

Thought I'd lose my balance with the grounds bounce and sway.

And all this violence. And all this goes away.

And the vibes that rise like fireflies illuminate our play.

Some like being pulled up from night's party.

Said clap your hands if you think your soul is free.

And the silence was astounding.

Except some, oh Lord!! Mercy Me's.

And oh you can't stop what's coming up.

You're never gonna stop gonna live it up.

And oh it's gonna drop gonna fill your cup.

And oh it's gonna drop gonna fill your cup!

The age of miracles.

The age of sound.

Well, there's a Golden Age coming round, coming round, coming round.

TUCKER: On that song, "Golden Age," TV On The Radio mixes David Bowie in his '70s disco mode with the approach to syncopated rhythm that Prince has perfected and come up with a song who's refrain is, there's a golden age coming around. Is the band being nostalgic, sarcastic, idealistic? There's an open-endedness to the band's lyrics that isn't really annoying, although here and there, their vagueness is coy so much as it is intriguing.

(Soundbite of song "Family Tree")

TV ON THE RADIO: (Singing) Now I'm no mad man, but that's insanity,

Feast before famine and more before family goes,

And shows up with more bowls and more cups,

And the riot for the last hot meal erupts,

Corrupts his hard drive through the leanest months,

Shells out the hard cash for the sickest stunts,

On aftershave, on gasoline.

He flips the page and turns the scene.

In my mind, I'm drowning butterflies

broken dreams and alibis,

That's fine.

I've seen my palette blown to monochrome,

Hollow heart clicks hollow tone.

It's time.

TUCKER: Well, there's eclecticism for you. That song begins with a spoken section that's not rap but more of Broadway musical, a gloss on Meredith Wilson's "The Music Man." It then slides into a slippery funk groove with a jolly pop sing-song chorus. It's this kind of bursting inventiveness that keeps you off balance listening to TV on the Radio in a state of constant ear-opening surprise.

GROSS: Ken Tucker is editor at large for Entertainment Weekly. He reviewed "Dear Science" by TV On The Radio. You can download podcast of our show on our website, freshair.npr.org.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

95980398

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.