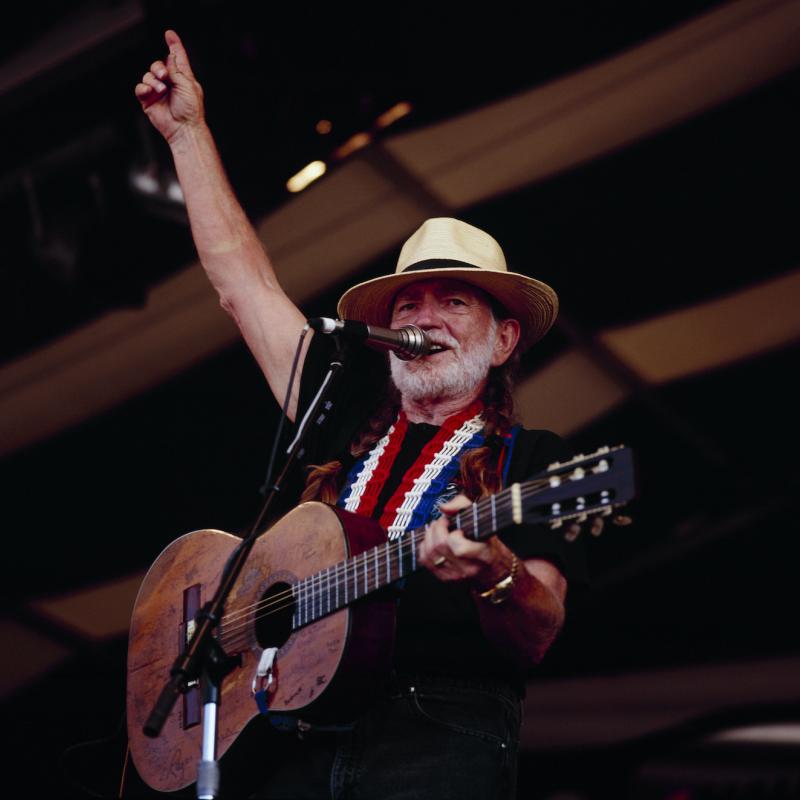

Willie Nelson Sings 'Crazy' and More on 'Fresh Air'

Willie Nelson turns 70 years old next week. We mark the occasion with a 1996 interview and in-studio performance; the country-music icon tells Terry Gross about the genesis of songs like "Family Bible" and "Crazy" — the song Patsy Cline turned into a country classic — and gets out his guitar for intimate, idiosyncratic performances of several landmark tunes.

One don't-miss moment: The audibly bemused reaction from Fresh Air's usually unflappable host when Nelson describes writing "Crazy," "Nightlife," and "Funny How Time Slips Away" — all in a single week. That was just before he headed from Houston to Nashville in his '46 Buick.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on April 25, 2003

Transcript

DATE April 25, 2003 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Filler: By policy of WHYY, this information is restricted and has

been omitted from this transcript

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Movie "Better Luck Tomorrow" about overachieving

Asian-American teen-agers

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

"Better Luck Tomorrow" is a new, low-budget, independent film about the double

lives of a group of overachieving Asian-American teen-agers. It was first

shown at the Sundance Film Festival in 2002 where some outraged audience

members complained of what they thought were negative images of Asian-American

youth. The movie was picked up by MTV Films and film critic John Powers says

"Better Luck Tomorrow" signaled a new wave of Asian-American movies that are

freer in content and style.

JOHN POWERS reporting:

Back in the mid-1970s, Maxine Hong Kingston wrote her great novelistic memoir,

the "Woman Warrior," about growing up in Stockton, California, haunted by her

mother's stories of China. For the next 25 years, the prototypical story

about Asian-American life was an assimilation drama about the gap, even the

clash, between Old World values and the younger Americanized generation.

But as Asian-Americans have grown more and more assimilated, they begin to

find a new tone, breezy, satiric, slightly cynical. That's precisely what you

get in Justin Lin's "Better Luck Tomorrow," a zesty new black comedy about

brainy Asian-American teens in the gated suburbs of Orange County, California.

Based on real-life events, it's a topsy-turvy tale of American success that

one might call "Goodfellas Part II: The Honor Roll."

Newcomer Parry Shen plays the narrator hero Ben, a teen-age kid who's almost a

parody of the Asian-American overachiever. He boasts a sterling GPA, joins

high school clubs because it will look good on college applications and he

makes the basketball team. But he's actually bored by all this

resume-building stuff. And, along with his aggressively nerdy pal Virgil,

he's looking for action. It comes in the form of the sociopathic Daric,

played by Roger Fan, a smug, good-looking fellow student who insists, `We

don't have to play by the rules. We can make our own rules.'

The guys start out selling classroom cheat sheets, but soon they're dealing

drugs, handling stolen goods and, like all good gangsters, carrying guns. Yet

even as Ben enjoys being bad, he longs for a mysteriously unattainable

cheerleader who may or may not have been in a porn film. But she's involved

with a rich kid, a prep school Lothario named Steve. Through it all, Ben

keeps on being a model student, working hard at self-improvement.

(Soundbite of "Better Luck Tomorrow")

Mr. PARRY SHEN ("Ben"): I shoot 215 free throws a day. My goal is to beat

Calvin Murphy's record of 95.8 percent. That's 207 baskets.

Punctilious, marked by or concerned about precise, exact accordance with the

details of codes or conventions.

To get a perfect score in my next SAT, I need to improve my verbal score by

60 points. I picked a new word every day and repeated it over and over again.

They say if you repeat something enough times, it becomes part of you.

Punctilious, adjective, marked by or concerned about precise, exact

accordance with the details of codes or conventions.

POWERS: You can get away with anything if you're clever enough, Ben says at

one point, and this might almost be the credo of director Justin Lin. He

knows the drudgeries and rebel dreams of kids like Ben and he fills the movie

with good jokes about everything from tokenism in school athletics to the

absurd rigors of the academic decathlon. Clearly delighted to show A

students gone wild, Lin topples time-honored stereotypes of dorky, docile

Asian students like the egregious Long Duk Dong, from Johnny Hughes' old

film "16 Candles." And he spotlights some young actors worthy of other big

roles. Baby-faced Parry Shen is enormously likeable as Ben. Jason Tobin's

Virgil has the comic ferocity of an egghead Beavis. And then there's John

Cho, a sardonically handsome actor who makes the prep school Lothario the

movie's defining character, a young princeling who feels contempt for a

privilege he doesn't really want to give up.

I saw "Better Luck Tomorrow" with a young Asian-American audience who howled

at its social satire. They laughed at jokes I didn't even know were jokes.

But they drew quiet during the last half-hour, as the fun turns dark. The

problem wasn't simply the violence but Lin's failure to face up to the bleak

reality he's showing. The movie falls into a round of retribution and wish

fulfillment so half-hearted in its cynicism that you can tell that Lin's

actually too nice a guy to relish the amorality he appears to be courting.

Lin's moral condition finds an echo in his characters. Instead of being

caught halfway between the old world and the new--these kids are wholly

American after all--Ben and his pals appear stranded in some eerie future.

They inhabit a hypermodern suburban world scrubbed clean of the past. It

feels less like a community than some weird test tube that spawned smart,

bored kids who feel entitled to the world's plenty, yet also disdain what it

brings.

Naturally, we never see any parents. In fact, the only adult who remotely

registers in "Better Luck Tomorrow" is a science teacher played by Jerry

Mathers, the erstwhile Theodore Cleaver, who was clearly cast for his

symbolic significance. The aging Beaver's clueless benevolence evokes an

idealized, white, middle-class childhood that these days is more a punch line

than anything resembling the American Dream. For Ben and his friends, such

corn-fed innocence is as remote as anything that their folks would have known

back in the Old Country.

BIANCULLI: John Powers is film critic and columnist for LA Weekly.

(Credits)

BIANCULLI: For Terry Gross, I'm David Bianculli.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.