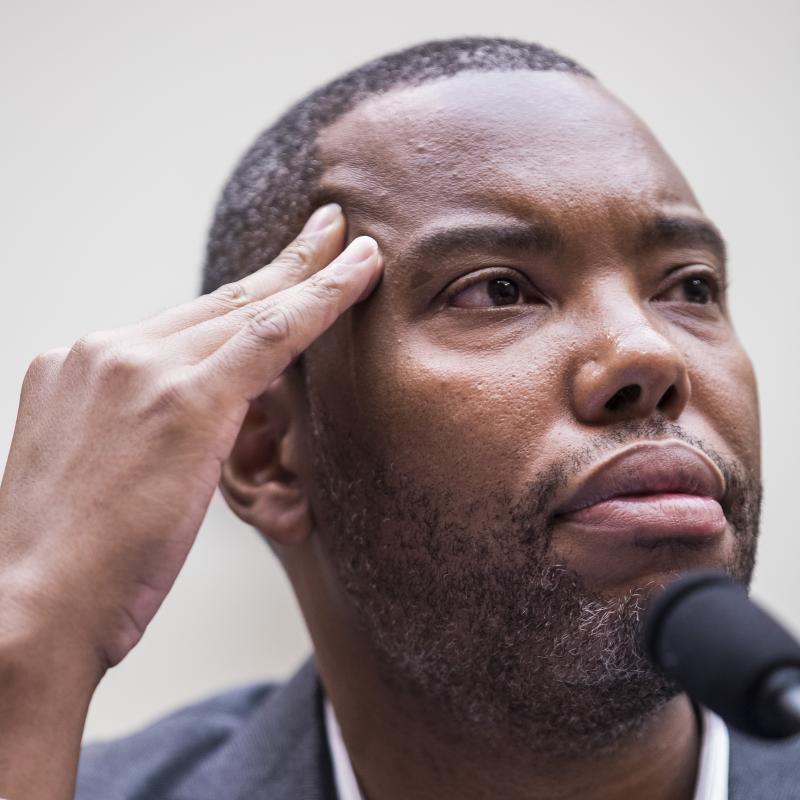

Ta-Nehisi Coates On Magic, Memory And The Underground Railroad

After writing three non-fiction books dealing with race and identity, and relaunching Marvel's black superhero series Black Panther, Ta-Nehisi Coates has written his first novel. Set during slave times, it re-imagines leaders of the underground railroad as having a magical power to help people out of slavery.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Transcript

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. My guest, Ta-Nehisi Coates, has written his first novel. But the subject matter is connected to stories, issues and ideas he's written about in his nonfiction. He won a National Book Award for nonfiction in 2015 for "Between The World And Me," which was written in the form of a letter to his son about the different forms of violence young African Americans are especially vulnerable to.

Coates' Atlantic magazine cover story, "The Case For Reparations," led to a national conversation about how to reckon with today's injustices resulting from years of slavery, Jim Crow, separate but equal and racist housing policies. Coates also relaunched Marvel's comic book series "Black Panther" before the movie adaptation was made. His new novel, "The Water Dancer," is set in slave times. Yesterday, Oprah named it as her next book club selection.

The novel imagines an underground railroad with leaders who have a magical power to help deliver slaves to freedom. The main character, Hiram, is born into slavery. His white father is his owner and the owner of the plantation. His mother, a slave, was sold by Hiram's father when Hiram was a young boy. Hiram's half-brother Maynard is white and is therefore Hiram's master, although Hiram is the intelligent one, the reliable one, the strong one, and Maynard is a fool.

Let's start with a reading from the opening scene. Hiram is driving Maynard in a horse and carriage on a rainy day. As they cross over a bridge, it collapses beneath them, plunging them into the water. As Hiram struggles to keep from drowning, Maynard pleads for Hiram to save him.

TA-NEHISI COATES: (Reading) There I was, my own life dangling over the black pit and now being called to save another. I had on many occasions tried to teach Maynard to swim, and he took to this instruction as he took to all instruction, careless and remiss at the labor, then sore and bigoted when this negligence bore no fruit. I can now say that slavery murdered him, that slavery made a child of him. And now, dropped into a world where slavery held no sway, Maynard was dead the moment he touched the water.

I had always been his protection. It was I, only by good humor and debasement, who had kept Charles Lee from killing him. And it was I, with special appeal to our father, who'd kept him countless times from wrath. And it was I who clothed him every morning, and it was I who put him to bed every night. And it was I who now was tired in both body and soul. And it was I out there resting against the pull of the current, against the fantastic events that had deposited me there and now wrestling with the demand that I once again save another when I cannot even conjure the energy to save myself.

Help me, he yelled again. And then he cried out, please. He said it like the child he always was, begging. And I noted, however uncharitably even there in the Goose facing my own death, that I had never before recalled him speaking in a manner that reflected the true nature of our positions. Please. I can't, I yelled over the water. We are under the ox.

GROSS: Thank you for reading that. That's Ta-Nehisi Coates reading from his new novel, "The Water Dancer." Ta-Nehisi Coates, welcome back to FRESH AIR. So Hiram, the African American character who was a slave at this point, is saved through a magical power that we'll only come to understand later in the novel. You'd written the "Black Panther" comic book series, the series that's also the basis for the film "Black Panther." And, of course, there are magical powers in that. Did you borrow some of the thinking of magic and of - almost like of superheroes and think, what if some of those powers could have been used in history to save people from slavery?

COATES: No. No. There are two things going on in terms of why that - that's in the book and why it exists in the book in the way that it does. The first is, you know, who I am, you know, as a kid, you know, came up in Baltimore in the '80s and read a lot of comic books, listened to a lot of hip-hop, played a lot of Dungeons & Dragons. My roots are low and pulpy in fantasy and sci-fi.

But there's a second, I think, much more important thing. And that is, you know, in order to write "The Water Dancer," before I even knew, you know, that I was writing "The Water Dancer," I did a considerable amount of research. And when you look at how African Americans described themselves during that period, when you look at how they talk about their own escapes from slavery, magic is often very much a part.

Frederick Douglass, when he makes his first escape attempt from enslavement on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, he talks about a dude who gave him a magical root, which he, you know, felt would imbue him with powers. Slaves would talk about - in their oral narratives about, when running and outwitting the hounds and the dogs, putting graveyard dust in their shoes. If you look at, you know, in Louisiana, the Native Guard, when they die - when one of their commanders died in a battle down there, they held a seance to try to commune with his spirit to bring inspiration.

And it just goes on. There are countless examples of that all through the literature. And so what "The Water Dancer" does, you know, it evokes obviously, you know, my own taste. But I think, much more important than that, it tries to take a somewhat forgotten tradition in African American resistance and render it seriously.

GROSS: So the magic in this novel requires memory and the power of story. Why memory? I mean, because memory's also history. It's like personal memory, and it's also an understanding of the past. Why did you want to make that part of the requirement for conjuring the power?

COATES: You know, it's tough for me to answer why. I think probably the honest answer is, at least for the past 10 years in a lot of my writing, I've thought a lot about memory and why certain things are remembered a certain kind of way. And I've thought quite a bit about the fact that, you know, much of the country's history is premised on forgetting, not remembering certain things. And so it felt sort of natural, actually, to go in that direction, to reach there as a source. Why I did that - I mean, it's - I guess I was just captivated with the idea, you know, of why we remember and why we don't.

GROSS: But memory is power in your novel.

COATES: Yeah.

GROSS: Do you think of memory as power?

COATES: I do. I do, actually. You know, one of the big, I think, themes, you know, for Hiram, is he - because his mother's gone, because his father's actually sold his mother, he starts off the novel in great admiration of his father and in great admiration of the lineage and all of the, you know, sort of things that make the plantation where he's enslaved, Lockless, to be this sort of great place. And even as an enslaved person, he actually admires them.

And what he has to come to realize is how much of all those great things that he admires is actually based on not just the exploitation of the enslaved population there but on forgetting the things that have been done, forgetting how that exploitation actually happens, not seeing it. You know, he talks about being in the house and all the devices and the way the house was designed to obscure slaves from view so that you thought the entire house was powered by some sort of magical force.

And what he comes to realize is that, in fact, escaping, you know, all of those accoutrements of high civilization, you know, of great Virginia society, is actually the true freedom. It's freeing to live down in the dirt, down in the muck, as he says, as opposed to have to, you know, construct yourself as a kind of god.

GROSS: He also talks about how the closer you get to the slave owners, to the plantation owners, and the closer you see the wealth that they have, the more you understand what they've taken from - he says, the more you understand what they've taken from us.

COATES: Yeah, exactly. Exactly. And...

GROSS: And so it's a burden to be close to them and to be near that power because you see what it's cost you.

COATES: Yeah. And you see them in a very, very intimate way (laughter). And so then you have the ability to assess, you know, is this person actually smarter, you know, than this guy, you know, who I was just down in the fields with? You know, is he somehow, you know, a better person? Is he, in any way, more entitled to all of these riches? You get to see the degree that that, in Hiram's case, his enslavement - specifically his brother, you know, and his father - are directly dependent upon him and the rest of the enslaved populace and really can't do anything without them.

GROSS: To write this book, did you have to imagine what life would have been like if you were a slave? And did you have to imagine if you would have the strength and the endurance and the courage of some of your characters?

COATES: I did, but not just the courage and the strength and endurance; I had to imagine their weaknesses, too. I also had to imagine myself as an enslaver. You know, I had to imagine myself as Hiram's father, had to imagine myself into Hiram's brother. So not just, you know, the - I don't know, some of the more admirable characters in the book because I felt really, you know, strongly and feel really strongly that enslavement is a system. And while there are, you know, some individuals of particular, you know, high courage, courage is not a thing to be counted on when it comes to systems.

So I had to, you know, imagine, you know, Hiram's father, for instance, as a relatively decent dude, as far as, you know, that can go, as, you know, a dude who loved Hiram about as much as the system would allow. And yet...

GROSS: Because he owns Hiram. He's a slave owner.

COATES: He is. He's a slave owner, yes. But at the same time, you know, is capable of great evil, you know, nonetheless.

GROSS: So tell me about imagining yourself as a slave owner in order to write the book.

COATES: So I feel like that was not maybe as new as it sounded. I think, like, history becomes - and maybe moral problems in general - become really, really easy if you can't see yourself in the people that you condemn because then you just get to feel better than people. You know, I would never do X, Y and Z. You know, we would never do, you know, this and that. But, in fact, you know, if - you know, at least my investigations of history and my reading, what you often find is people who are absolutely, you know, brilliant sometimes, sometimes can, you know, totally see the moral failing that, you know, that they're committing and yet still continue to commit the moral failure.

I mean, the example that immediately comes to mind is, you know, for research for the book I went to Monticello. And, you know, a significant part of going to Monticello was grappling with Thomas Jefferson. If you ever want to read the most eloquent denunciation of enslavement by an actual enslaver, you know, it doesn't get much about than Thomas Jefferson's notes on Virginia. Jefferson can explain how, you know, slavery not just robs enslaved people of their due, but actually corrupts the enslavers and actually even corrupts their children - some beautiful, beautiful passages.

Still in all, he is a man who lived luxuriously off of the labor of literally hundreds of enslaved people and did not, you know, just live in a normal fashion but lived, you know, in debt, so much so that when he died, actual, you know, people there had to be sold in order to settle his debts. You know, is it that Thomas Jefferson couldn't see what was wrong? You know, is it that Thomas Jefferson was, you know, just, you know, a person lacking courage? Or is it much more likely that he was a human being who was a child, you know, of people who had enslaved, that - who lived in a society in which people enslaved, who had many friends who enslaved, who lived in a state that, you know, was rooted in enslavement?

When you can think about it that way, you know, how can you say that you somehow would have necessarily been any different?

GROSS: Let me reintroduce you here. If you're just joining us, my guest is Ta-Nehisi Coates. He has a new novel called "The Water Dancer." We'll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF GAIA WILMER OCTET'S "MIGRATIONS")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is Ta-Nehisi Coates. He has a new novel called "The Water Dancer."

So you've kind of reimagined the Underground Railroad in this novel, and you know, Harriet Tubman is a character in it. Hiram, the main character, becomes a part of this underground. But as we talked about before, there's an element of magic in how this underground manages to free slaves. Can you describe the magic as you've created it?

COATES: Yeah. So maybe I - let me just back up a little bit because really this starts with Harriet Tubman. You know, I'm from Maryland. My family is from the Eastern Shore of Maryland, where Harriet Tubman's - you know, was enslaved and is from. And so when I was a child, like, Harriet Tubman was a near mythical - an actual mythical figure. And you know, the stories we would hear about them - some, you know, rooted in history; some, you know, exaggerations - just seemed wild.

I mean, who is this person who has fainting spells and yet has never lost the paths? Who is this, you know, black woman in the 19th century who, when, you know, somebody is scared and wants to turn back, pulls out a gun, you know, and making threats - you ain't turning back? You know, (laughter) who is this person, you know, who just strides through history, you know, in this sort of way? Because, you know, at that point, you know, in the 1980s, when I'm growing up in Baltimore, you know, we didn't really have people like that. Harriet Tubman stands out, you know, in the landscape of myth and American history, but also stands out among African American - you know in the African American pantheon and is just a different kind of, you know, figure.

And so I've always been entranced by her. And I can remember I was reading a biography of hers, and the biographer was making a point that many of the escapes that Harriet made folks can't - like, historians can't quite figure out how she did it. And whenever I hear, we don't know how this happens, like, my mind starts turning, you know. I start (laughter) imagining things. And you know, as I said, you know, at that period in time, I was done quite a bit of research. I was reading a lot about, you know, escapes, and a lot of these escapes were rendered, you know, in the literature as harrowing flights. You know, they had a kind of adventure quality to them, and that really just, you know, matched my own tastes.

And then, at the same time, I was thinking about, you know, the power of memory at that point. And I thought that it would be a very, very interesting allegory, almost, or metaphor to basically analogize memory with freedom and forgetting with slavery.

GROSS: So let's get back to the magic that you created for the book. I want you to describe it, if you can.

COATES: Sure. In its simplest terms, there's certain people - Hiram being one, Harriet Tubman being another - who have the ability to tell stories. And by telling stories and stories that are closely related to themselves and related to their lives, it allows them to move across actual space, across geography. It's basically teleportation through storytelling. That's probably the simplest way to put it. Although, that makes my skin crawl, saying it that way.

GROSS: Why did you think that the magic you wanted to create would be about teleportation, as opposed to any other form of, you know, magic or conjuring you could've come up with?

COATES: Well, you know, there are a couple of things. The first is obviously, you know, what Harriet Tubman is doing is actually literally moving people.

GROSS: Right.

COATES: And so the actual, you know, movement, you know, would be the, you know, the important thing in that case. But I think even more than that, one thing I was very, very conscious of in writing this book is that I wanted to write an adventure story that felt, you know, very conscious. You know, I was, you know, going back to my sort of pulpy genre roots. But there are elements of the adventure story that I did not want. And - for instance, I didn't want revenge. I didn't want, like, a violent power. You know? I didn't want, like, fire or something like that. I wasn't really interested in that because I think that actually evades one of the more interesting aspects of African American history, and that is that vengeance has rarely been a luxury that black people have had.

I think about Isabel Wilkerson's book, "The Warmth Of Other Suns," which is the history of the Great Migration. And that was, like, one of the first places where I had - where the Great Migration was presented as resistance that I had actually read about. You know? She has this, you know, beautiful sentence at the end of a passage early in the book. And she says, you know, basically, black folks in the South who were suffering under Jim Crow did what, you know, what people who are resisting everywhere, you know, often do when, you know, they can't, you know, outright resist. They left.

And I had never thought about leaving as resistance, even though it seems so obvious. And so I didn't want, like, the cowboy tropes. I didn't want guns. I didn't want, like - I don't know, like, you know, fire coming out of people's hands. That felt like it was evading, you know, some central point that I was trying to make at the time.

GROSS: So in addition to creating, like, a magical teleportation power and an imaginary - like, a fictional, imagined version of the Underground Railroad, if it could access such a magical power, you've made up new words. I mean, not new words, but you've used different words to describe things in your book. Like, this magical power is called conduction - which is interesting because, you know, there's conductors on the Underground Railroad, right?

COATES: Of course.

GROSS: And then the slaves are the tasked. The slave owners and the white people who run the plantation are the quality. Why did you want to create new words, and why those words?

COATES: So when I first got the idea to do this book - even though it wasn't quite this book - I mean, one of the great points that my editor made was, like, you know, you are not going into new territory. You're actually going into very, very well-tried territory. And so I wanted to write a book that had a portrait of my enslavement. And I don't mean as in, you know, me being enslaved, but what it felt like to me, what it seemed like to me. And so to do that, I wanted, you know, where I could, to have a different vocabulary, to have a different way of doing it, to have the lens, you know, be different.

There are other things that, you know, are different about it, too. But specifically, you know, I thought, you know, vocabulary was actually a strong part of that. The interesting thing is, almost all of the words that, you know, you've picked up on as new or, you know, maybe repurposed - maybe we should say that. Or remixed, or whatever...

GROSS: Repurposed is good. Yeah.

COATES: Yes. Yes. Yes. They come from - like, I pulled almost all of those out of slave narratives. Now, they might not have been used the same way. I mean, but you just saw it yourself. You know, you said, well, you term this power of conduction, which is interesting because, you know, folks working on the Underground Railroad, you know, considered themselves conductors. And it used - they use conduct as a verb, too. He was - you know, such and such was conducted on this date.

And I always thought that was so beautiful. I thought that was just such a, you know, a beautiful turn of phrase. And so it felt natural to adopt it. There are other words I didn't get to use. You know, for instance, I always liked - in Philadelphia, William Still's group was called the Vigilance Committee. And I thought that was so cool (laughter). But I couldn't figure out how to get it in. You know?

And in the same way, you know, when, you know, describing Virginia, in describing the enslaved. The task system is a system of labor, actually. I don't think they actually had it in Virginia, but they would have it in places like South Carolina. And it was a way of working. And I liked that word. I liked the immediacy of it. And so, you know, I picked up on it. Describing those who don't own - white people who do not own slaves as low whites, that's, you know, very much within how they would describe that at the time by certain people. Not, you know, by themselves. By certain people, both black and white.

But it also reinforces an idea that the true marker (laughter), of your morality, at least, from the perspective of the white society and where you exist in society, is actually your ownership of black people - that the ownership of black people is what makes you, quote-unquote, "quality." You know, it's the ownership, you know? And the ownership of larger numbers of black, I should say, is what distinguishes you from being a quality white and a low white.

GROSS: My guest is Ta-Nehisi Coates. His new novel is called "The Water Dancer." After a break, we'll talk about the impact that his 2014 article, "The Case For Reparations," had on his life and about testifying on the subject before a House Judiciary Committee in June. And we'll talk about writing the Marvel comic book series "Black Panther." I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Let's get back to my interview with Ta-Nehisi Coates. He won a 2015 National Book Award for his book "Between The World And Me," which was written in the form of a letter to his son about the forms of violence young African American men are vulnerable to. He wrote a now-famous cover story for The Atlantic in 2014 titled "The Case For Reparations." He relaunched the Marvel comic book series "Black Panther," before the movie adaptation was made. Now he has a new novel called "The Water Dancer." Yesterday, Oprah named it as her next book club selection.

So as we've been discussing, like, your novel is set during slave times. The main character is a slave who becomes part of the Underground Railroad and is able, eventually, to harness a magical power to help free people from slavery. So memory is very important in the novel because it's a memory that enables him to grasp this power and use it. And so in regard to memory and to learning things about the past, that - it's not like you remember them, but you've learned them through - they're part of, like, historical memory, what do you know about your own ancestry? It seems to me, like, writing this novel would make you, like, interested in going back generations and seeing what you found in your family tree.

COATES: Yeah. Well, more than I knew five years ago. I got really lucky because I was on that show that Skip Gates has.

GROSS: Oh, yeah.

COATES: "Finding Your Roots." And I know quite a bit, you know. I already - you know, one of the - I think the most interesting thing to me is, I always, you know, knew that my mother's side of the family was from the Eastern Shore of Maryland. I knew that my dad's, you know, family was from Philadelphia, but originally, you know, for a long time, it wasn't clear whether, you know, they had, you know, just been in Pennsylvania or whether they had come from somewhere else. Eventually, we realized - or we discovered, you know, through the show that they actually came up through Virginia.

And so while the ancestry of the enslaved is really important, one of the things that I think about all the time is, they actually were two very different kinds of families. My mother's family, from the oldest ancestor that we can actually trace - is a woman whose race is ambiguous, who might have been white, might have been mixed. We're not sure. But she was free. And then her child was free, and I'm talking about the early 1800s. And she had land, and her child had land.

And so up until, you know, even, you know, the beginning of my lifetime, my family from the Eastern Shore of Maryland has always had land, you know, in their life. My mom grew up, you know, going down to the Eastern Shore. And there was always - even as my mother grew up in the projects, there was always a kind of prosperity that was around them. It's very, very tough to describe because it's not actually material, you know, wealth necessarily. They're not rich, but it was a different kind of poor. And in my dad's family, man, I mean, it really felt like the other side of black America or, you know, almost a stereotypical side of black America.

You know, my dad, as I wrote about, you know, in "The Beautiful Struggle," his father died, you know, when he was very, very young. He only knew his father until, you know, age 9. Two of my father's brothers died. My father's grandfather, as we, you know, discovered through "Finding Your Roots," was crushed in an accident at a meatpacking plant - just a variety of issues.

And when I looked at how the two sides of my family actually lived, I could not escape the fact that, in fact, on my mother's side of the family, they had always had land. They had always had a level of wealth that was not present - so even though both families come out of enslavement, the fact that one was freed a lot earlier, the fact that one was given, you know, certain things some 200 years ago, that actually - like, I could actually see the effects. This is to say nothing about a white family who's had the luxury of such things for, you know, centuries, you know, that would go back to the Mayflower or something like that.

GROSS: Do you know if there were any white slave owners in your family tree?

COATES: Yeah, I'm pretty certain there were, you know. A - I took a DNA test, so you start there.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Yeah.

COATES: So that pretty - yeah, that pretty - I mean, they - you know, you can never, you know, be too sure of this stuff. They gave me of rough range between 15% and 25%, you know, basically European DNA, which is about the average for African Americans. You know, the African American average European DNA is about 20% or so.

GROSS: So one of the things that you're so well known for is an article that you wrote for The Atlantic and - was it 2014, "The Case For Reparations?"

COATES: Yep, 2014.

GROSS: And so you used the example of housing discrimination. And I just want to back up and say, it's so relevant to what we're talking about now because your book is about slavery...

COATES: Yes.

GROSS: ...And how it disadvantaged people for centuries. I mean, people are still dealing with the consequences of their ancestors having been enslaved and deprived of money, land, freedom, education and so on - their children, their parents who were sold. So you wrote this article in 2014, "The Case For Reparations," and you focused on housing discrimination and as an example of white-imposed disadvantage, as you described it. And so that really helped just kind of, like, restart a big national debate about, should there be reparations, and if so, what do we mean by it, and what would that look like?

And so every year since 1989, after John Conyers introduced his idea to have a commission to study reparations - every year, that idea for a commission to study reparations was introduced into Congress. And this year, there was actually a House Judiciary subcommittee that started talking about that, and you testified at that. And I'm not sure if what I read was an excerpt of the whole thing, of your testimony, but what I read focused on Mitch McConnell.

COATES: That was most of my testimony, yeah.

GROSS: So why, making your pitch to this House subcommittee about reparations, did you want to focus on Mitch McConnell, the Senate majority leader?

COATES: Because - yeah, I had actually started, you know, writing - I knew that, you know, I was going to do a testimony about a week or two before, and so I'd actually started writing out my testimony. Then somebody asked Mitch McConnell about the hearings; a young African American reporter asked him the question. And I felt like what he said, which is that, you know, we don't have to - you know, basically, we aren't accountable for things that happened 150 years ago, and you know, we, you know, elected a black president, so therefore we should, you know, be past it.

I thought that summary - it was a perfect summary of - or perfect encapsulation of the argument I wanted to attack, and that is that somehow history, or American history, is only relevant when it credits Americans. Any time, you know, it says something bad about the country, it is somehow, you know, oh, that was a long time ago and has no relationship to today.

GROSS: Have you gotten to the point of thinking about what reparations might look like? Or is your goal just to say, this is something we should be talking about?

COATES: The answer is yes to both. Yes, I - let me take the latter part first. I am trying my best, perhaps somewhat unsuccessfully, to stay out of the world of activism around reparations. It's just not - it's not who I want to be. I want to be a writer, you know? I believe in reparations, but I don't think my talents lie in organization or advocacy or anything like that. I think I'm where I'm supposed to be. At the same time, how can you not think about, you know, what it might - would look like?

And so I've given some consideration to it, and I think the first thing to understand is that reparations is not unprecedented, that we've actually done this, you know, before. We did it - you know, and I'm sure, you know, you've heard this yourself. You know, we did it for Japanese Americans who were interned during the period of World War II. The state figured out how to compensate the victims of that internment.

We have a reparations program right now, actually, in Chicago, Ill., for the victims of a police officer by the name of John Birch who, for decades, tortured African American men and tortured confessions out of them. And the City of Chicago made a reparations settlement that included cash to the victims but also included a curriculum so that, you know, schoolchildren in Chicago would understand who John Birch was and what the police did, you know, in that era.

There's been reparations payments made for massive resistance in Virginia when the state of Virginia effectively - or certain counties in the state of Virginia - basically shut down the public school system in order to resist Brown v. the Board. And so I've always thought about reparations as not merely you take a DNA test and you get reparations, but as a literal suite of claims. It's the reason why I focused on housing discrimination specifically, housing discrimination as a claim for reparations.

And I think, like, you know, taken together, you know, like, when you think about - right? - white supremacy, what you think about is several harms inflicted, you know, upon a group of people, you know, at varying levels. And in my mind, a reparations program takes each harm individually, tries to locate the victims - the people who've actually, you know, been affected by that harm - and then tries to compensate them for it.

GROSS: What has the impact on your life been of the reparations article?

COATES: Oh, that's a great question. Wow. So what I would say is "The Case For Reparations" and "Between The World And Me" taken together - because one came out one year and the other came out the other year - they - I don't know. They fundamentally changed my life, you know? They made me - boy, it's hard to say this. They made me famous, I mean, as much any writer can be famous. You know what I mean? As much as anybody can be...

GROSS: No, it's true. It's a fact.

COATES: Yeah. I mean, I don't like saying it, though.

GROSS: It's not - you're not bragging. It's just - it's a fact.

COATES: Right. What you're probably picking up on is my discomfort around that fact. It made me famous. You know, I - you know, I won't skid around this at all. It gave me a level of, you know, financial stability that I had never, like, you know, come close to, you know, or touched or imagined. And what that meant was that I could do things like go off and finish a novel like this, you know? It meant that, you know, the way I saw my work was fundamentally different. I could, you know, now really, really imagine - what do I actually want? What I actually, you know, want to do as opposed to going from story to story or book to book?

I think it changed how people saw me. I think sometimes, because of that, you know, fame and celebrity, people probably attribute more qualities to me than I am in the possession of. A lot of times, people think because you're intelligent or smart about one thing and you're famous so a lot of people see you be intelligent and smart and wise on one thing, they necessarily assume that you are smart and wise on all things or that you have the ability to speak on all things, and, you know, that just is not the case.

What I do is much more based in, you know, research and trying to understand than it is in, like, snap analysis - you know, looking at a situation; saying, this is what it is. I'm actually not that quick, you know? I'm not a, you know, particularly quick thinker. I'm a much slower thinker, but that might not be obvious, you know, when I'm talking about some that I've thought about for a really, really long time.

And so I say that to say that it probably imposed, you know, things, you know, on me that I was not particularly comfortable with. But at the same time, you know, you get some good and you get some bad, you know? There's no, you know, unalloyed blessing. There's no, you know, good thing that happens and then not, you know, responsibilities that come with it.

GROSS: So you have to - do you have to be clear with people about what you're not going to do because it's not where your talent lies and where your interest lies or where your heart is?

COATES: Yeah, all the time, and they look at me like I'm crazy (laughter). They look at me like I'm crazy. Like, they're like, what? You know what I mean? And when you say that, like, they think you're, like, putting them off or blowing them off or something, but I - listen. You know, for better or worse, I'm a writer, you know? And I don't - you know, I don't have much else.

I'm not particularly good at politics. I can't really work a room, you know what I mean? I'm not, you know, good, you know, at parties filled with people I don't know. That's not what I do. I'm not, you know, really good at talking to people and building consensus, you know, between, you know, broad groups of people. You know, I'm not an academic. I don't have much talent at, you know, designing, you know, programs, you know, to end, you know, great evils.

And so yeah, I have my limitations, you know, and I'm OK with that, you know? I'm OK with that. I am deeply honored that people look and maybe see more and than I see. At the same time, I think it's really important to know your lane.

GROSS: Well, let's take a short break here, and then we'll talk some more. If you're just joining us, my guest is Ta-Nehisi Coates. His new novel is called "The Water Dancer." We'll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF AHMAD JAMAL'S "THE LINE")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is Ta-Nehisi Coates. His new novel is called "The Water Dancer."

So I want to switch subjects here and talk to you about "Black Panther."

COATES: Sure.

GROSS: So the series was started - the "Black Panther" Marvel series was started in the late '60s by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. What was the original like? And - because the original was created by two white men set in Africa - I mean, the characters set in Africa, characters from Africa. I haven't read the original, so I don't know whether they're (laughter) - he's originally - whether Black Panther's originally in other Marvel character stories or if it's set in Wakanda.

COATES: Sure.

GROSS: But - anyhow. (Laughter) So what was the original incarnation of Black Panther compared to how you portrayed him?

COATES: So he starts off actually in the "Fantastic Four," which was, you know - which is, I guess, to this very day Marvel's, you know, flagship comic book. And eventually he's in the "Avengers," which is another, you know, big, big comic book for Marvel. He, you know, at one point marries Storm, who is one of the X-Men. So, you know, Black Panther shows up in quite a few places.

You know, the thing to remember is he was created in 1960s. I think, consciously or unconsciously, there was a need to create a character who ran counter to stereotypes of what Africa was. So Black Panther is actually, you know, the king of this really, really advanced kingdom, you know. And so, like, the way he's portrayed is, you know, smarter than everybody, more prepared. You know, it's like the cardboard - you know, if you, you know, wanted to run exactly the other way, you know, away from, say, the natives and a Tarzan cartoon, that then you would have Black Panther.

So, you know, when I was writing him, or when I - you know, I'm still writing him, I was writing him today - I try to take that as accepted and not - I'm less interested in constructing a reaction or constructing - that reaction was necessary. It was important. But I just try to take that as a given and write about the man. You know, Black Panther is a dude who is a king of Wakanda but maybe would rather not be a king, you know? And that actually is the central conflict, you know, for me, you know, in the comic book, you know, not necessarily, you know, directly countering white stereotypes of Africa.

GROSS: When you're working with the illustrator who you work with, did you - when you started working with him, did you want the character drawn differently than he'd been drawn in the '60s? And I'll ask you the same about the women, how they were drawn.

COATES: Yeah, that's a great question. The character, not so much. You know, and I should be clear. You know, Black Panther appeared, you know, in the '60s, in the '70s, in the '80s, in the '90s. He's appeared quite a few times in the, you know, early 2000s, mine being just the latest rendition.

The Black Panther himself, not so much. I left that up to the artist. I have really strong feelings about the women, and less the depictions of women from the '60s, but more the depictions of women from the '80s on. In comic books in particular - this is not, you know, just true of "Black Panther" - women, you know, very often, you know, until very recently looked like porn stars, basically. That's how they're drawn.

GROSS: Yeah, exactly (laughter).

COATES: Yeah, yeah.

GROSS: (Laughter).

COATES: No, that's very, very - you know, I - and so I had to think about that. I had to think about that. And they're - I mean, there's a point in the first issue where it's two women who are in love with each other. And there's a very, you know, short and, you know, very subtle, you know, love scene. And, like, literally in the script, I had to write, listen, this can't be for us. You know, like, this can't, like, look like, you know, a bunch of dudes, you know what I mean?

GROSS: (Laughter).

COATES: You know what I mean? Like, looking at lesbian porn, that can't be what this is. This has to be for them. You know, you have to do it, you know. And so I will say because of the - and I've been generally lucky, you know, in terms of artists. But you - man, you really got to keep your eye out for it. It's, like, in the culture of comic books to draw women in that way, and it's a thing that you always, always have to correct for and think about.

GROSS: Let's take a short break here, and then we'll talk some more. If you're just joining us, my guest is Ta-Nehisi Coates. He has a new novel called "The Water Dancer." We'll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is Ta-Nehisi Coates. His new novel is called "The Water Dancer." So I want to ask you about swimming and drowning. In the opening...

COATES: Oh, wow.

GROSS: (Laughter) In the opening scene of your novel when two characters are drowning, the main character is describing the experience. And he says, (reading) there is no sensation like drowning because the feeling is not merely the agony but a bewilderment at so alien a circumstance. The mind believes that there should be air since there is always air to be had, and the urge to breathe is such a matter of instinct that it requires a kind of focus to belay the order.

I read that a couple of years ago you were taking swimming lessons.

COATES: (Laughter).

GROSS: (Laughter) And...

COATES: Wow, you really research. My God.

GROSS: But...

COATES: Wow (laughter).

GROSS: But I was...

COATES: That's a deep cut, Terry (laughter).

GROSS: (Laughter) No, but I was wondering if you were ever, like, afraid, uh-oh, I'm actually drowning, and had that experience of, like, wanting to breathe and not being able to.

COATES: No. But, you know, when I was learning to swim, the hardest thing to learn how to do - and I actually only learned how to do it on one side, which is why I'm such a weak swimmer - is the breathing, you know? The turning your head and timing when you're supposed to breathe and when you're not, you know, supposed to breathe and learning, you know, when you can't breathe and what's going to happen, like, when you breathe wrong and being shocked that that actually happens, you know, and learning as an adult - right? - you know what I mean?

So it felt really, really unnatural to me, you know, to learn to, you know, turn my - I'm literally turning my head in the studio right now as I'm talking to you - learn how to turn your head, you know, on your side and, you know, suck in the water and then breathe it out. Breathe out - like, learn to breathe out your nose, you know, which is what they tell you to do - once you stick your head in the water, and then at the same time, not breathe water back in - like, not automatically inhale, but just breathe out. Turn.

That was - that took a lot, you know? And so I probably - not probably; I did - I extrapolated from that the idea of disorientation, the idea of - like, what? I can't breathe right now. I'm supposed to be able to breathe, you know what I mean? All of that actually comes from the period of me learning how to swim. That's great.

GROSS: Was it empowering to learn how to swim as an adult?

COATES: Yes. And it felt like - it actually felt like an act of resistance, you know, weirdly enough, because I had, you know, learned how to swim a little bit but not really, you know, as a child. And I knew that one of the reasons why I didn't really, you know, learn how to swim as well as, you know, some of my peers that I was around, you know, here in New York City had, you know, very much to do with how I grew up. There weren't really a lot of good public pools.

I can remember a few years ago going out to California and, you know, walking along the beach, seeing all of these little kids learning, you know - they were, like, in surf school. They were learning to surf, and they couldn't have been any older than, you know, 10 - you know, maybe 11 at the oldest. And I thought, that is incredible. Like, I didn't even know things like that actually existed. And so, like, learning to swim, for me, was probably part of this period in my life when I've had the luxury to go back, you know, and study things and learn things that I just didn't have the luxury of having, you know, as a child.

And for me - and this will take us right back to Hiram, by the way - for me, like, when I think about enslavement and when I think about oppression - and this is just personal. This is me. I wouldn't make this as a broad, categorical, global argument, but one of more painful aspects, you know, in addition to being separated from your family, is the inability to feed your mind - like, to be curious about certain things, to want to know how to do certain things and just not be able to do them.

And so on the one hand, while I wasn't exactly, you know, always happy with what happened after "Case For" - you know, "For Reparations" and after "Between The World And Me," it afforded me the luxury of really going back, you know, and studying certain things that I had wished that I had done as a kid. You know, foreign language is another one. You know, French - studying French was another example like that. So yeah, it was very empowering.

GROSS: So one more question for you - "Between The World And Me" was written as a letter to your son expressing your concern about the things he might be vulnerable to as a young black man coming of age in the U.S. Have there been any unintended effects of that book on your son?

COATES: Yeah, probably. I think I'll know a lot more when he's probably, like, 25 or 30.

GROSS: After he's in therapy (laughter).

COATES: I mean, one - you know, I'm in therapy, so, I mean - so, you know, he might be in therapy regardless of whether that happens. Therapy's a great thing. But I think...

GROSS: Yes, it is. I wanted to agree with you on that.

COATES: Yes. But I think he'll know more, and I'll know more. Once, like, you can reflect back - it's, like, tough to see when you're in it. He is really proud. That's the first thing, obviously. He's extraordinarily proud, so one thing I have not had is, like, you know, any sort of, like, resentment between the two of us. But I think, like, I'm really proud of him, even though it sometimes gets him into trouble. I'm really proud of him because he understands the space I occupy in the world, and he is extremely loath to make use of that space to make his life easier.

And again, I mean, sometimes, it gets him into trouble to the point of, you know, like, being, like, really independent about things where I'm like, man, you could have just asked me. You know, it's just me being your dad. I could've told you X, Y and Z, you know? But I think, you know, he's very set on making his own way, and if I had to choose between that and, you know, some kid who just wanted to, you know, loaf or whatever, I would definitely, you know, take the former, you know? So we'll see what the effect is. You know, I think, you know, one of the big things, as I said, is just, you know, him being much more intent on making his own way.

GROSS: Right. OK. Ta-Nehisi Coates, it's been great to have you back on the show. Thank you so much.

COATES: Thanks for having me, Terry.

GROSS: Ta-Nehisi Coates' new novel is titled "The Water Dancer." Tomorrow on FRESH AIR...

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "BACK IN THE SADDLE AGAIN")

GENE AUTRY: (Singing) I'm back in the saddle again.

GROSS: ...We'll talk about a wonderful but largely forgotten chapter of music history, cowboy songs. My guests will be Doug Green. He's the author of a book about singing cowboys. He sings lead in a cowboy music band, hosts a cowboy music show on the satellite radio channel Willie's Roadhouse and he's featured in Ken Burns' "Country Music" series on PBS. I hope you'll join us.

FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our interviews and reviews are produced and edited by Amy Salit, Phyllis Myers, Roberta Shorrock, Sam Briger, Lauren Krenzel, Ann Marie Baldonado, Mooj Zadie, Thea Chaloner and Seth Kelley. Therese Madden directed today's show. I'm Terry Gross.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "BACK IN THE SADDLE AGAIN")

AUTRY: (Singing) Back in the saddle again. Whoopi-ty-aye-yay (ph), I go my way. Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.