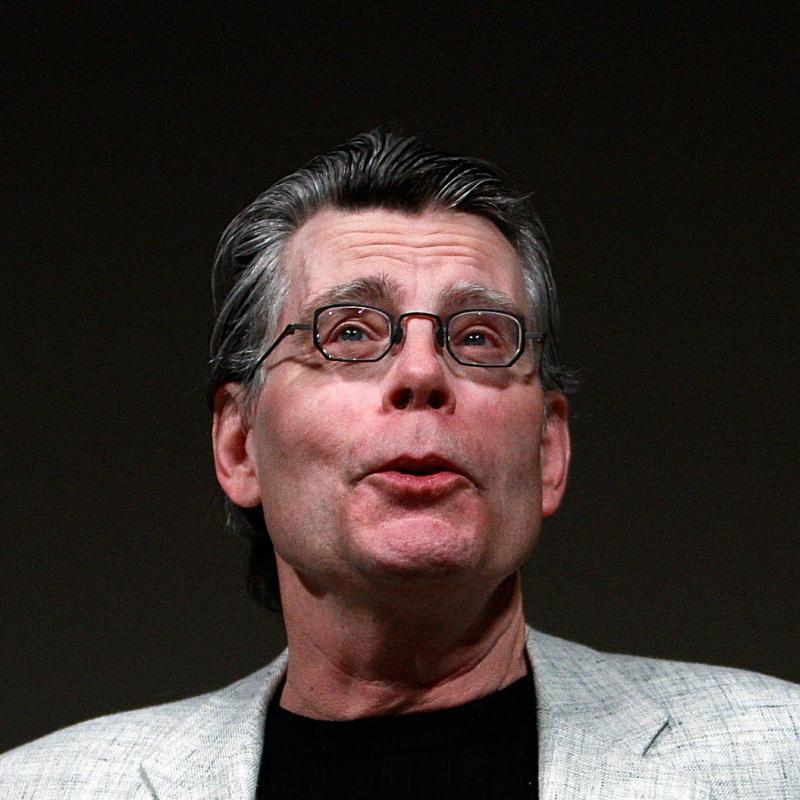

Stephen King Is Sorry You Feel Like You're Stuck In A Stephen King Novel

In his 1978 novel The Stand, author Stephen King wrote about a viral pandemic that decimated the world's population. And he gets it when fans say experiencing the COVID-19 outbreak feels like stepping into one of his horror stories.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Transcript

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Life during the pandemic has been feeling like living in a Stephen King novel, so let's see what Stephen King has to say about it. He's my guest. About 40 years ago, in his novel "The Stand," he wrote about a virus far worse than COVID-19. It was 99% lethal and wiped out most of the population. That virus was accidentally released by a lab developing biological weapons.

Stephen King has a new collection of novellas called "If It Bleeds" that will be published April 21. The main character of the title story is private eye Holly Gibney, who was also a character in several other King books, including "The Outsider," which was adapted into an HBO series starring Cynthia Erivo as Holly. The series just ended a few weeks ago and is available for streaming and on demand if you have HBO. Like in "The Outsider," in "If It Bleeds," Holly is confronted by a force of evil.

Stephen King, welcome back to FRESH AIR. I am so glad that you are well. Is this pandemic the closest thing you've come to living in one of your own horror stories?

STEPHEN KING: (Laughter) Well, it is and it isn't. I had a lot of people get in touch with me after Donald Trump got elected and said...

GROSS: (Laughter).

KING: ...This is just like "The Dead Zone." There's a character in "The Dead Zone" named Greg Stillson, who is kind of an avatar of the common man. And he becomes a state representative, and then he rises to the presidency. So this is the second time. And now that Trump is actually president of the United States and there is a pandemic worldwide - I guess that's what pandemic means - that it seems almost like those two books have cross-pollinated somehow. It's not very comfortable to me. I keep having people say, gee, it's like we're living in a Stephen King story. And my only response to that is, I'm sorry.

GROSS: (Laughter) It's not your fault. Is there anything that's surprising you about how you're dealing with the fear and anxiety of the pandemic, since you created a far more lethal one?

KING: Well, the strangest thing to me about the way things have played out is the fact that people seem to have fixated on bathroom tissue, toilet tissue, toilet paper as the focal point for their anxiety. The shelves are totally empty of that stuff, and every time the stuff comes in, it disappears again. And I asked somebody at the supermarket, what is the deal with this? And they said, we have no idea what it is because there's no shortage. It's just that people are stockpiling that one particular thing.

But otherwise, you know, I see a lot of things that remind me of "The Stand." Obviously, there's not been a worldwide panic, but in "The Stand," people kept saying to the American public and the world public, don't worry about this. It's just the flu. Everything's OK. And so when things end, people die trying to escape from the cities, and the roads are crammed with dead vehicles. None of that is happening. But when you see pictures, like, of Times Square in New York or the freeways in Los Angeles, you say, yeah, this is really something that we've never seen in our lifetime.

GROSS: And I should mention, if you want to hear Chapter 8, it's on YouTube (laughter). The audiobook version of Chapter 8, which describes how the virus is spread in "The Stand" is on YouTube. But in "The Stand," the president says, and we'll have a vaccine in a week (laughter).

KING: Right.

GROSS: Are you reminded of things that you're hearing, the kind of underplaying of fear and the optimism about how, yeah, we've got a solution right around the corner?

KING: Here's the thing about COVID-19 - something like this was going to happen. It was inevitable that this would happen. When I wrote "The Stand," I think it was in 1978 and '79 - right around that time - I went to Russ Dorr. The new book, "If It Bleeds," is dedicated to Russ because after he retired from his job as a physician's assistant, he worked for me as a research assistant for many years. And "The Stand" was the first project we worked on together.

And I said, I'm looking for a virus that would be deadly. And he said, well, the common flu keeps changing. It's a shifting antigen virus so that the shot never works two or three years in a row because the flu changes and you get sick and you have to get a new shot. Well, there's no shot for COVID-19 yet because this is something that just sort of burst out upon us. But it was bound to happen. There was never any question that, in our society, where travel is a staple of daily life, that sooner or later there was going to be a virus that was going to communicate to the public at large.

So what you end up with is - first of all, we had a president and we had an administration that was in total denial about this for the first vital period of time - let's say January, February, March, where the president is saying things like, well, don't worry about it. It's really no more than the common cold. And his cheerleaders on the right side of the political spectrum are jumping in. And the most insidious thing about it is that you don't have just one Typhoid Mary who can spread this because the disease is communicable but not active in that one particular person; you have huge numbers of people who are carrying this, and they feel terrific. They're out there.

So that, for instance, when President Trump says, well, I'm not going to wear a mask. You might want to wear a mask. You might not. I'm not going to say that you should. But probably you should - that sort of thing. The thing that that is not addressing is the fact that you don't wear a mask because you're afraid somebody else will make you sick; you wear a mask because you might be a carrier and you might make them sick. So this is a very difficult disease.

GROSS: I want to get back to how you're dealing with the pandemic after having created one over 40 years ago for a novel. You created, like, a worst-case scenario pandemic that kills most of the population, and then society has to basically rebuild itself. So, like, you built in fear. I mean, you write horror stories. You write things intended to scare people. So how are you dealing with living with fear and anxiety?

KING: Well, the short answer to that is I'm not. What I'm living with and what I suspect a lot of people are living with right now is cabin fever. Everybody sees the news reports. They see the hospitals that are crammed. But they also understand that, for most people, if they catch this thing, they're going to kick it. The body is going to kick it out. There's going to be some mild symptoms, and then it's going to go away. You just hope that you're on the good side of that equation. And the odds are stacked in the favor of people who are going to get coronavirus and survive it.

On the other hand, we realize that there are people out there, like Adam Schlesinger, who is one of my favorite composers, one of the founders and one of the creative forces behind Fountains of Wayne, and he died at the age of 52, so that - it can happen. We all hope it won't happen to us, and we take reasonable precautions.

But to be in the house day after day (laughter), all I can say is I've made wonderful progress on a novel because there's really not too much to do, and it's a good way to get away from the fear. It's not panic. It's not terror that I feel, that I think most people feel; it's a kind of gnawing anxiety where you say to yourself, I shouldn't go out. If I do go out, I might catch this thing, or I might give it to somebody else.

GROSS: I want to get back to the idea of a virus. You know, you write horror stories, and a virus is kind of perfect. Like you said, you know, viruses are shape-shifters. They keep - like, the flu virus keeps changing every year or two. That's why we always need new vaccines. And viruses aren't exactly alive because they can't - they need some kind of living cell to inhabit in order to survive. So I think scientists say that viruses aren't really alive, or they're somewhere between alive and dead. That sounds kind of like a horror story.

And the fact that they live in us and, like, we are their hosts and then they make us sick and, in some cases, can kill us, that really - like, that's the kind of thing you could have invented from scratch. But viruses are real. Do you think of viruses as being just, like, the essence of a horror story in how they work in us?

KING: Yes, I do. You know, for years, I was...

GROSS: Oh, can I add one more thing?

KING: Yes.

GROSS: You can't see them. Like, you write sometimes about the kind of evil that - like, it can manifest itself in a presence. It can manifest itself in a person. But it exists as an entity. It exists just as pure evil, too. And with a virus, like, the entity, you can't see it unless it's in a body. I mean, you could put it under a microscope, but without a microscope, you can't see it. You don't know it's there, but it is. That's like a horror story, too.

KING: It is. And when you were talking about viruses not being alive or dead, this really is like one of those zombie movies. It's the - you know, the night - we're living in the "Night Of The Living Dead" in a sense because the virus is just what it is, which is something that's almost incomprehensible to us. And it's incomprehensible to science, too, which is one of the reasons why I think people have to watch out for quack cures.

The thing is, because it's invisible, because we can't see it, we hear these things on the news where they're saying, look - if you have to go out, make sure that you don't touch your face. When you come back in, make sure you wash your hands. Be careful about taking off your shoes, and when you take your shoes off, put them in a certain place, and then wash your hands because you can get the virus on your shoes. So that after a while, I think that a lot of people in America, maybe even a majority of people in America, are living almost like Howard Hughes, who had this...

GROSS: Yes. Yes.

KING: ...Pathological cleanliness thing. We're all washing our hands. And it's easy to imagine - Terry, think of this. They could be on your hands right now - germs, viruses, like wagon wheels just they're in your hands, waiting to get inside the warmth of your body, where they can multiply and spread. And once you start thinking about that, it's very hard to unthink it again. So it's easy to start to be paranoid about it. But on the other hand, what's the alternative?

GROSS: I'm glad you mentioned Howard Hughes because I keep thinking about the scene in Martin Scorsese's film "The Aviator," where Leonardo DiCaprio as Howard Hughes...

KING: He's in the bathroom, isn't he?

GROSS: He's in the bathroom, exactly. And he's trying to get out of the bathroom, but because he's so compulsive about washing his hands and cleaning his hands, every time he washes his hands he has - he can't reach the door with a paper towel.

KING: He can't - yes.

GROSS: And so he can't get out because every time he touches something, he has to go back and wash his hands again, and the scene keeps going on. And that's the world I feel like I'm living in right now. I'm not sure I have any skin left on my hands (laughter) from washing so much.

KING: Yeah. Oh, that's the...

GROSS: Do you like that scene? I know you...

KING: Yeah.

GROSS: Yeah.

KING: I was thinking about that scene, just as you were and as I'm - I'm sure a lot of people who've seen that movie can relate to that immediately, you know, to the idea of these things are all over our hands. We're making complexes in our children that are going to last a generation. You know, for me, as a guy who is in his 70s now, I can remember my mother talking about the Great Depression. It made a scar. It left trauma behind.

And I think that for our children, when they grow up - or let's put it this way - my grandchildren, when they grow up, my granddaughter who can't see her friends, can only Skype them once in a while. She's stuck in the house. She can go out in the yard. When her children say, oh, my God, I'm so bored, I can't go out, that little girl who becomes a woman is going to say, well, you should have been around in 2020 because we were stuck in the house for months at a time. We couldn't go out. We were scared of germs. You see what I'm saying?

GROSS: I think you're absolutely right. I completely - I feel exactly the same way.

I think we'd better take a short break here. If you're just joining us, my guest is Stephen King. His new collection of novellas is called "If It Bleeds." We'll talk more after we take a short break. This is FRESH AIR

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to my interview with Stephen King. He has a new collection of novellas called "If It Bleeds."

I want to read something that you recently wrote. And I think it was in a tweet, if I remember correctly. People writing novels, including me, set in the present are going to have to rethink a great deal of their works in progress. To quote Bob Dylan, "things have changed." So are you in the middle of something? And are you rethinking it because you know the world is changing around you, and there are changes that are going to be long-term or permanent?

KING: I am in the middle of something. I've been working on a book since last April, I think, since - yeah, since about the spring of 2019. There've been a lot of things that have sort of interfered with the progress of this book. But it's marching now. And it's largely marching because I'm stuck in the house and I have no (laughter) excuse to procrastinate. I have to do this.

But my idea originally was - the book, "If It Bleeds," is out this year in 2020. So I set this book in the year 2020 because I thought, OK, when I publish it, if it's in 2021, it will be, like, in the past, safely in the past. And then this thing came along. And I immediately looked back through the copy that I'd written. And I saw that one of the things that was going on was that two of my characters had gone on a cruise on a cruise ship.

GROSS: Oh.

KING: And I thought, well, no. I don't think anybody's going on cruise ships this year. And so I looked at everything. And I immediately set the book in 2019, where people could congregate and be together. And the story would work because of that. There are a lot of interesting ramifications - that word again - to think of with this.

I can remember when the Cold War more or less ended. And people said, well, I don't know what spy novelists are going to have to write about now. Well, of course, they found things to write about. And writers will find things to write about with this. I don't know whether it will be love in the time of coronavirus or exactly what it will be. But there will be novels.

But for people who are writing books occurrent, right now, I would just say, take a look at the TV ads that run on the news. The news is running all coronavirus all the time. Everything else has been pushed to the sidelines of this. But when you see the ads, they still show people congregating together. They are in car dealerships. They're shaking hands. The grandfather is still with his kids. And he's saying the big, bad wolf huffed and puffed. And the kid says, sort of like you, grandpa, right?

GROSS: (Laughter).

KING: Well, those people are not together anymore. The ads are, basically, obsolete, totally obsolete.

GROSS: You know, I have to say - I don't know how closely you worked on the HBO series. It was so good. And I want to recommend it to anybody who has access to HBO who's looking for something to stream. And although it has its evil and its scary moments, it's not related to the kind of thing we're going through right now, exactly. So what do you think, Stephen?

KING: Well, I loved the series. I loved what they did to it. The guy who developed it, Richard Price, is a fantastic novelist. And I'm a longtime fan of his work. He does a...

GROSS: Me too.

KING: He does a lot of police procedural stuff - very tough, very gritty, nuts and bolts. He knows a lot about that sort of thing. And I was stunned to learn during my relationship with him and the emails that we had back-and-forth that he's also a huge horror fan. And he's read a lot of my stuff. He knows all the classic writers like Arthur Machen and H.P. Lovecraft.

And so he was eager to try and combine the two, which was one of the interesting things - one of the things that I really loved about writing "The Outsider" was I was able to take police work and a very rational who-done-it or how-done-it story about a man who could be in two places at the same time - there were witnesses that said, yeah, he was there. And he must have killed this child. But there are other credible witnesses who say he was 90 miles away at a conference. So I had a chance to use the - all the bells and whistles of police procedurals, which I also love, and combine them with the horror story.

GROSS: Well, let's take another short break here. And then we'll talk some more. If you're just joining us, my guest is Stephen King. His new collection of novellas is called "If It Bleeds." We'll talk more after we take a short break.

I'm Terry Gross. And this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MICHAEL KAMEN'S "OPENING TITLES")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Let's get back to my interview with Stephen King. He has a new book of novellas called "If It Bleeds" that comes out April 21. The main character of the title story is Holly Gibney, who's been in several other King books, including "The Outsider," which was recently adapted into an HBO series starring Cynthia Erivo as Holly. The series just ended a few weeks ago.

The character in the title story of your new collection, Holly Gibney, is also in "The Outsider" and several other of your novels. So Holly Gibney, she runs a detective agency. Do you consider her to have a obsessive compulsive disorder or to be on the autism spectrum or to have just, like, a little bit of psychic ability? How would you describe what her...

KING: (Laughter).

GROSS: ...Makeup is that gives her a kind of special power, a special insight?

KING: Well, first of all, can I say that I just love Holly. And I wish she were a real person and that she were my friend because I'm so crazy about her. She just walked on in the first book that she was in, "Mr. Mercedes," and she more or less stole the book (laughter). And she stole my heart.

(LAUGHTER)

KING: But the short answer to your question is, I see the Holly of the books as an obsessive compulsive with a huge inferiority complex. The character, the Holly that Richard created, was more of a, I would say, on the autism spectrum, kind of a - what do you call a person who is just very capable in one area, you know, somebody who can do numbers in their head, boom? Holly - that Holly, Richard Price's Holly of the HBO series is that kind of person where she can remember who did every rock song for 35 years, but she's never listened to a record.

GROSS: Do you believe that some people have special powers of perception?

KING: Oh, yeah. I've seen it. I know that - I used to be good friends with Stephen Jay Gould. We shared seats at Fenway Park. And he would bring his son along. And his son was on the spectrum. But he would say to you, tell me what your birthday was and how old you are. And if you did that, he would immediately tell you the day you were born on. He just had that particular talent in his head. There are kids who can suddenly sit down and play the piano. They just hear the music in their heads and - or there are kids who are 7 or 8 years old who are chess prodigies. That's the word I was looking for, prodigies.

And so, yeah, there are people who have those special powers. And one of the things that fascinates me about this whole spectrum that I write in, which is a pretty wide - people can call me a horror writer if they want to. And that's fine. As long as the checks don't bounce, I'm happy with that. But I think that I do a lot more. And I'm interested in the mystery of what we are and what we're capable of doing.

GROSS: You know, in the opening to the Holly Gibney story in "If It Bleeds," your new book, you mentioned that the detective who worked with Holly in the book "The Outsider," that his perception of reality was totally changed by that incident because he's dealing with something beyond our perception. He's dealing something that doesn't seem rational or scientific, which is just this entity of evil.

Do you feel like you live in a different reality than other people? (Laughter) You know what I mean? Because you're always writing about things that are outside of our perception and that are outside of what we consider to be, you know, the real visible, perceivable world.

KING: Yeah. I hear your question. And I think the answer is that, 20 hours a day, I live in the same reality that everybody else lives in.

GROSS: (Laughter).

KING: But for four hours a day, things change. And if you ever ask me how that happens or why it happens, I'd have to tell you, it's as much a mystery to me as it is to anybody else. All I know is that when I sit down in front of the - well, it's a word processor now. It used to be a typewriter. Well, it's actually a computer now. Things change.

And in all the years that I've been doing this since I discovered the talent when I was 7 or 8 years old, I still feel much the same as I did in the early days, which is, I'm going to leave the ordinary world for my own world. And it's a wonderful, exhilarating experience. I'm very grateful to be able to have it.

GROSS: Why did you leave your - you know, the actual, you know, world for your world, but make your world such a frightening world?

KING: Well, I am interested in frightening people, actually. I'm like the little boy in the Charles Dickens story - I just want to make your flesh creep. And that's OK. But what I'm really interested in as a writer that I come back to time and time again is the intrusion of the unexpected and the strange into our everyday life. And I think that that's a kind of - an honorable theme, because we all face unexpected things. We're going through one now as a society. I'd love to think that it would bring us together. I'm not sure that that will happen.

But certainly, we're all faced with dealing and integrating into our world view the empty streets, the empty stores, going in the supermarket once a week instead of, you know, just, like, oh, my God. Wait a minute. I ought to go pick up a frozen pizza. You go in there and you see people wearing face masks. Four weeks ago, that would've been crazy. You would've thought that they were robbers or something. So I like to explore that world where something strange happens to ordinary people.

GROSS: In "The Outsider" - and this is also mentioned in "If It Bleeds" - you refer to the story of El Coco, which is a kind of mythical story that has its origins in various, you know, Spanish, Hispanic cultures. Why don't you describe El Coco and why you're interested in that story.

KING: I found El Coco after I had started to work on "If It Bleeds." I knew that there was an outsider because that's what the book was about. I'm interested in exploring the idea of outside evil. I find it comforting to think that there can be evil that doesn't necessarily come from the hearts and minds of men. And once I had set up this situation where there was a creature that could take the face and the form of someone else - who could become that person's doppelganger, I looked around for myths that would play into that. And the one that I found in a children's book, actually, was El Cuco.

GROSS: So describe El Coco.

KING: Well, El Coco is a creature that lives on the fear and the pain of other people. In the myths, he takes bad children. He's a very thin man in a black coat with a white face. And what you tell the children - because we save our scariest stories for the children - is that if you're a bad kid, you will probably see El Cuco crawling on your ceiling. I just love that image because it's spider-like - the tall thin man in the black coat. And he carries a bag with him. And if you're a bad child, he will pop you into his bag and take you away to his lair, which is supposedly a cave. And at that point, he will kill you and rub that child's fat on his body and regenerate and be a young person again.

GROSS: Wow. That's a lot (laughter) - there's a lot in that story. But the idea of this El Cuco feeding on fear and on grief - I mean, that's when you're at your most vulnerable.

KING: Yeah, it is. And one of the things that I found extremely powerful that I wanted to use was that El Cuco only starts by getting someone - it's Terry Maitland in "The Outsider" - to take the rap, if you will, for his crime. But then that creature hangs around and feeds on the grief and the pain and the hurt of all the people that are left behind. The whole family the whole Frankie Peterson family ends up destroyed because of El Cuco, and El Cuco tries to do the same thing to Terry Maitland's family, starting with the kids, who are the most vulnerable.

So - but I liked that idea. I used the cave idea at the - for the conclusion of the book and the miniseries, too, where I was able to put El Cuco actually in a cave. So I stuck to the legend as much as I could.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Stephen King. And his new collection of novellas is called "If It Bleeds." We'll talk more after we take a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF W.G. SNUFFY WALDEN'S "HEADIN' WEST")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to my interview with Stephen King. He has a new collection of novellas called "If It Bleeds."

You grew up in the Methodist church. You went to church as a child. Given your bent as a writer, were you especially interested in stories about Satan?

KING: No, I wouldn't say I was especially interested in stories about Satan. I was more interested in the idea that Satan causes us to do terrible, terrible things. And the story I would say that fired my imagination the most was the story of Job. And I loved the language in that, the Old Testament - the King James language, where the story starts by saying that God says to the devil, what have you been up to, Satan? And Satan says, oh, I've been going up and down upon the earth to see what misery I could cause.

And so then they make a bet about Job, who basically is this sort of schmoo who's not doing anything wrong. And God says, do everything to him you want to do - just don't harm a hair of his head - and we'll see what happens. So the guy's crops die. The guy's livestock dies, then all his kids die. And after all that - this is where it kind of lost me - it actually has a happy ending (laughter). Job remarries and has more kids.

KING: So tell me more about why you find that story so interesting.

KING: Well, I think mostly because the idea that the devil can meddle in human lives, which goes back to the whole idea of whether or not - this is a question that's fascinated me all my life. Is there such a thing as outside evil? Are there demons, devils, ghosts, possessions, horrible things that come to us from outside, or is it all built into our DNA? The Bible likes to have it both ways. There's this story of Job where the devil kind of - the devil and God, in concert, cause all these things to happen. And then there's the story of the tree of good and evil, where you sort of get it all blamed on Eve, who just - man, she couldn't stop looking at that apple and saying, that must really be good - or the stories of Moses and all the people who built the golden calf because that's human failings - that it's human weakness. So I like to - I think it's actually comforting to think that there's an outside evil that's not our fault.

GROSS: That's a theme in "The Outsider" - so continues to be of interest to you, obviously. You know, on your website, under the frequently asked questions - I forget what the question is, but the answer is...

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: The answer is that you no longer attend church but you do believe in God and you read the Bible. I remember the last time we talked, you said that you've kind of willed yourself to believe in God. But, you know, you're - you have a lot of doubts. But anyway, so obviously you read the Bible. I mean, you're talking about stories that have special interest for you. What do you look for when you read the Bible now? Are you reading the Bible for religious reasons or for reasons about ways of understanding human life and human emotion? And...

KING: Well, I think, really, what interests me the most about the Bible - first of all, Terry, I'm a writer. I love the language. I listened to the Bible last year on audio. I think it was, like, 40 hours or 45 hours or something like that. It's not quite as long as "The Stand" on audio, but it's pretty long.

GROSS: (Laughter) Yeah, "The Stand's" over a thousand pages.

KING: It's true. And the Bible is only, like, 850.

GROSS: (Laughter).

KING: But I love the language of it, particularly the King James. It's beautiful to listen to. It's liquid, and it's rhythmic. I love some of the things, some of the lines that pop up again and again, the kind of incremental repetition of it. There's this thing in the Old Testament where they talk about people who will be cut off as men who pisseth against the wall, and I just think to myself, what a way to put it. I mean, that is, like, totally original, and it's great.

But the real purpose to me, I think, is because you see the way that human ethics and human law has developed. It's particularly interesting to me to go from the Old Testament, where people are cut off, don't suffer a witch to live - that sort of thing - to the New Testament, where Christ says, I give you a new commandment; love your neighbor as yourself. There's nothing like that in the Old Testament. So you see this kind of evolution of human thought that's wonderful. But the language is great.

And the other thing that's great is, as you listen, you find phrase after phrase that's crept its way into our language, and I love that. But mostly, yeah, it's the language. It's the stories. I'm sorry because it reminds me - makes me think of W.H. Auden saying, thou shalt not read the Bible for its prose. But I have a tendency to do that.

GROSS: I remember when I interviewed you after the publication of your book "Joyland," and we were talking about religion. You said at some point, if this is God's plan, it's very peculiar, and you have to wonder about his personality (laughter). I'm wondering if you're feeling that way now with the pandemic.

KING: Well, the pandemic could be a lot worse. I mean, I don't mean to sound like an old Jewish grandmother, you know, oy vey, it could be worse.

GROSS: (Laughter).

KING: It could be worse. The house could be on fire, you know. But it's not as bad as it could be. I mean, it - there are questions that always come up in everybody's mind. I've been writing about this. There's a character in the new book that I'm working on who says - after something really terrible has happened to her, she says, well, everything happens for a reason. And the main character in the book gets very angry about that and says, my sister died a terrible death; please don't tell me that someone else or something else was more important to God than my sister, and she was just a steppingstone.

So that when terrible things happen - and, of course, I made a career of writing about terrible things - there's always the question of, why would those things happen, and is there a reason for them to happen? And the nice thing about fiction, plotted fiction, the sort that I write - not that my plots are very tightly wrapped - is that there is a reason; we do see that's a rational universe. I'm not so sure we live in a rational universe.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Stephen King. And his new collection of novellas is called "If It Bleeds." We'll talk more after we take a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSETTE EXPLOSION'S "DOUCE JOIE")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to my interview with Stephen King. He has a new collection of novellas called "If It Bleeds."

I want to read something that you recently tweeted - if you think that artists are useless, try to spend your quarantine without music, books, poems, movies and paintings. What led you to write that? Do you think people think of artists as useless?

KING: I didn't write it. I saw it on Twitter myself and reposted it. I didn't make a comment or anything. I just put it up. I never thought anybody would assume that I had written that. But it got an awful lot of retweets. And what struck me about it when I put it up was that we all need escape hatches, even in the most ordinary times, when we could go out and we can have social intercourse with people, we can meet on the street, we can gab, we can go to a movie. Oh, my God, Terry, how I miss going to the movies...

GROSS: Me, too.

KING: ...You know, just sitting there with a - oh, yeah. I miss being with people. I miss going out to a restaurant and sitting, you know, and talking with somebody and having fun. Can't do that. I'm in the house. And I think that if I didn't have a good book to escape into - I'm reading this wonderful book now called "Dare Me" by Megan Abbott. Wonderful story. I've got Netflix. Thank God for Netflix. I'm watching this wonderful series called "Babylon Berlin."

So I can leave coronavirus. I can leave the self-quarantine and go back to Berlin in 1929. It's an escape hatch. It's a way to use your imagination as a force for good, where you can actually - by making believe, you can increase your serenity. You can take a little vacation from everything that's going on. That's the purpose of art. And it doesn't have to be a TV show, and it doesn't have to be a movie. It can be a poem. It can be going outside and looking at the spring that's just starting to come.

I think - every day, I like to take a few minutes to say, this is my life; I'm present in my life at this moment, and this is what I see, and this is what I feel. I think that you can't spend your whole day doing that. You'd go right out of your ever-loving mind. But once in a while, it's a good thing, and the imagination is a good thing.

It's not always so good in the middle of the night, you know, when you wake up and you think, I think I heard something under my bed. That's maybe not such a good thing. But it's a double-edged sword. There's a good side. There's a bright side to the imagination, and there's a dark side to it. And I'm sure that we've all been there. And I hope that tonight, Terry, when you go to bed...

GROSS: (Laughter).

KING: ...That you'll keep your feet under the covers because it would be awful, and I wouldn't want you to think about this after the lights go out. It would be - please don't think about a hand creeping out from under your bed...

GROSS: (Laughter).

KING: ...A cold hand and then lightly gripping your ankle. I mean, you won't think about that, will you?

GROSS: No, I won't because that's not what's going to be scaring me in the middle of the night. And you know what is going to be scaring me in the middle of the night. But which makes me wonder - like, how do you feel about your stories in a time like this? And what I mean is, your stories are about human nature and human vulnerabilities and the things beyond our perception, and they're also intended in part to scare people. You like scaring people. Part of your stories have to do with the world of horror. And we're surrounded by such - we're living in a horror story now. So what do you see as the role of, you know, horror fiction or horror movies in a period when the world itself is so frightening?

KING: Well, they're like dreams, aren't they? You're able to go into a world that you know is not real. But if the artist is good - the filmmaker or the novelist, maybe even the painter - for a little while, you're able to believe that world because the picture of it and the depiction of it is so real that you can go in there. And yet there's always a part of your mind that understands that it's not real, that it's make believe.

GROSS: Stephen King, thank you so much for talking with us. Thank you for your books. And I wish you and your family good health. And be well. Thank you.

KING: Thank you. And right back at you - be healthy and be safe.

GROSS: Stephen King's new collection of novellas is called "If It Bleeds."

Tomorrow on FRESH AIR, my guest will be San Francisco's new DA, Chesa Boudin, who's been dealing with the impact of COVID-19 on the criminal justice system in his city and is concerned about the spread of the virus among incarcerated people and the people who work in jails and prisons. His father is serving a life sentence in a New York prison. Chesa Boudin is an advocate of reforms to address racial and economic inequities in the criminal justice system. I hope you'll join us.

To our listeners who begin celebrating Passover this evening, we wish you a good Pesach. One of the four questions asked at the Seder is, why is this night different from all other nights? And as the friend of one of our producers says, no need to ask why this Passover is different from other Passovers. If you're having an Internet Seder, I hope it enables you to feel connected to loved ones while you all stay safe.

(SOUNDBITE OF PAUL SHAPIRO'S "MA LECHA HAYAM")

GROSS: FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our interviews and reviews are produced and edited by Amy Salit, Phyllis Myers, Sam Briger, Lauren Krenzel, Heidi Saman, Therese Madden, Mooj Zadie, Thea Chaloner and Seth Kelley. Our associate producer of digital media is Molly Seavy-Nesper. Our technical director and engineer is Audrey Bentham. Roberta Shorrock directs the show. I'm Terry Gross.

(SOUNDBITE OF PAUL SHAPIRO'S "MA LECHA HAYAM")