Other segments from the episode on May 7, 2013

Transcript

May 7, 2013

Guests: Patricia Volk - Martin Scorsese NEH Lecture Excerpt

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Some girls grow up feeling almost embarrassed by how their mothers dress and look. Nowadays that might mean mom jeans and hair from two decades ago. But it was the opposite for my guest Patricia Volk when she was growing up in the '50s. Her mother was beautiful and stylish, and everyone made a point of telling her: the dentist, the doorman, her teachers, cabdrivers.

Beauty and the preservation of that beauty was very important to Volk's mother. Patricia Volk knew she could never measure up to her mother in that category, but she found an alternate way of thinking about fashion and beauty from a memoir in her mother's book collection, "Shocking Life" by the fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli.

It was Schiaparelli's surrealist-influenced fashion and her personality that got the attention, not her face. Volk has written a memoir contrasting what she learned from her mother's conventional sense of beauty and being a woman with Schiaparelli's. Our book critic Maureen Corrigan said the book breaks new ground in terms of the memoir form and also the archetypal story of the mother-daughter bond.

Volk's previous book, "Stuffed," was about growing up in a Manhattan restaurant family. Her grandfather introduced pastrami to America. Patricia Volk, welcome to FRESH AIR. I'd like you to start with a reading from your memoir "Shocked." And I think a lot of daughters will relate to this.

PATRICIA VOLK: What do you do when you're little, and you know you can't be like your mother? I adore and am proud of my mother, but what she wants from me is blind adherence to the mystifying virtue of seemly behavior. Why must I sit with my ankles crossed? Why does she pinch my cheeks with rouge on her fingertips as I leave the apartment? Why are her parting words don't be loud?

In a race with a boy I have to let him win? Why does she care so much about how I look? When I get home from a party, her first question is: Were you the prettiest girl there? Is there a way to answer that that doesn't make you cringe? You don't agree with what your mother thinks is important. You don't want to care what she thinks. At the very least, you'd rather care less.

Your older sister tries to be like her. You watch. Over and over your sister fails. You want to be you, whatever that is, not your mother's idea of you. You don't know what it takes, how much of it is luck. You suspect you're going to be all right in the world. You hope you are. You yearn for a signal. You're ripe for it.

Sometimes it comes from a teacher or a relative. It could be a situation that shows you something about yourself you didn't know. Sometimes it's a book. There is a coincidence. I have no idea what it means. My mother wears Shocking perfume by Elsa Schiaparelli, and the book that diffuses her, the book that transforms me, is "Shocking Life" by Elsa Schiaparelli.

GROSS: That's Patricia Volk, reading from her new memoir "Shocked: My Mother, Schiaparelli and Me." Do you know, I was almost angry reading that your mother asked you if you were the prettiest girl at the party?

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Like you said, there's no answer you can give without cringing. What did you say when she would ask you that?

VOLK: I would just kind of shrug. Most of the time I said no, Mom, I wasn't. Bobby Finkelstein(ph) was there, and she's much prettier than I am. You know, but I would never say I was the prettiest girl there. It seemed vain and wrong. But I believe that when my mother went to parties, she looked around the room and felt she was the prettiest girl there. I hated the question.

GROSS: So you hated it when your mother asked you that?

VOLK: I hated it. It was like, you know, she didn't ask me if I had a good time, she didn't ask me if I - a boy asked me to dance. It was as if the only thing that was important was that I was the prettiest girl there. I didn't care about that.

GROSS: And the other thing is you weren't beautiful by your report. It's not like I saw what you looked like, but - but still you're born looking how you look, and sure you can put on makeup and have nice clothes and stuff, but in terms of like that idealized sense of beauty, either you have it or you don't. And to be constantly expected to measure up to an ideal of beauty that you're just never going to have just seems so almost cruel.

VOLK: Well, I was never going to have it. I looked like my father, although I think I was rather attractive but in a very different way than my mother, who was glamorous and a movie star. She had a movie-star kind of look. She was always compared to - people actually took sides. There was the Lana Turner camp and the Grace Kelly camp.

She had an icy blonde beauty, an imperious kind of beauty. And I was - that wasn't something that even appealed to me for myself, although I did bask in her glow. When people stopped me on the street and said little girl, your mother's so beautiful, or the shoe salesman would say do you know you have a very gorgeous mother, if I were a dog, I would have been wagging my tail.

I was just so happy for her. It was important to her. And it kind of rubbed off on me. But I didn't ever think I want to be beautiful like my mother. I just didn't. I thought it was a bit of a curse, actually.

GROSS: Why was it a curse?

VOLK: It was a curse because beauty is evanescent. And I knew my mother would get old. I had a grandmother who was considered so beautiful that she once received a letter, postman, postman, do your duty, deliver this letter to the Princeton beauty. And it got to her door. But she was a grandmother by the time I knew her, and she was no longer beautiful, and that was going to happen to my mother.

I knew early on that I wanted to be responsible for what made my life good. I didn't want it to be something God-given or something that could be taken away from me by time.

GROSS: What did your mother do to achieve her beauty in addition to just having a naturally beautiful face?

VOLK: Well, she did have a naturally beautiful face, and it was very symmetrical, which helped. But she had an elaborate makiage. And when I was a little girl, I loved watching her put on her makeup. I loved it, and it also disturbed me because it masked her face. By the time she was finished with all these layers of paint, she had actually put a mask of her face on top of her face.

She would put on so much Max Factor pancake makeup, which she sometimes called her base, that really her face was all even like the skating rink at Rockefeller Center. It was just this flat plain, and then she'd sculpt cheekbones in with what she called rouge, I guess they now call it blush, and then she'd put eyes back on with blue eye shadow and mascara.

And the whole thing took a long time, and she always wore this green velvet robe that I loved. And her vanity was entirely made of mirror. Even the wastebasket that came with it was made of mirror and the stool that she sat on. And when she finished, her final act, after all this makeup went on, was to dab behind her ears using Elsa Schiaparelli's Shocking perfume. And it came in a very elaborate bottle.

GROSS: And so your mother had Elsa Schiaparelli's perfume, Shocking, and your mother had her memoir, which you read and you found transformative. How would you compare Elsa Schiaparelli, the famous fashion designer, how would you compare her sense of beauty with your mother's sense of beauty?

VOLK: Well, Elsa Schiaparelli was quite different from my mother in terms of beauty. She was born with moles, raised black moles all over her face. She never had them removed. She had an older sister who was quite beautiful. She was said to look like the statue of Athena in the Vatican. But Elsa Schiaparelli's mother always told her she was ugly.

And she didn't feel good about herself until her uncle, who was the foremost astronomer in the world at the time, Giovanni Schiaparelli, and he was the head of the La Brera Observatory in Milan. And he took his little niece to the observatory, and he asked her to look in the telescope, and what she saw was the Big Dipper. And he said: That's what's on your face.

And from then on she felt quite attractive. She had a brooch made by Cartier that echoed the moles on her face, and she wore it under the moles. It became a source of pride for her that this constellation was on her cheek. But she believed in a kind of hard chic, very dramatic, that my mother would not have ascribed to.

Elsa Schiaparelli wore notice-me clothes, fabulous notice-me clothes, and my mother was much more demure. She revealed her body, but it was covered up. Elsa Schiaparelli invented see-through clothes, and she didn't mind wearing them. Although she said she was very shy, she would wear anything.

GROSS: Well, you know, in describing the difference between your mother's sense of beauty and designer Elsa Schiaparelli's sense of beauty, you say that Schiaparelli wore clothes as theater, and it wasn't about making you more beautiful. You say whether you were beautiful or not, when you enter a room wearing something designed by Elsa Schiaparelli, your clothes are the star. An unattractive woman and a beautiful woman become for a moment equals.

VOLK: Yes.

GROSS: So did you aspire to be that kind of clothing-as-theater person, or was she, was the Schiaparelli approach just a good counterpoint to your mother, making it seem like there were alternatives, that you didn't have to follow your mother's sense of beauty or clothing?

VOLK: Schiaparelli gave me an alternative way to be. I don't really wear notice-me clothes, but I do dress in a way that is something that pleases me. I don't know how other people react to it. I went through a vintage period that my mother was horrified by. She thought I was going to get bedbugs and lice and things. But I loved those old, drippy clothes. And I think I still do. I dress a little bit like a female Oscar Wilde.

(LAUGHTER)

VOLK: I just love those high collars and those lavish ties at the neck. There's just something wonderful about it. I think I'll just always do that. And I do like surrealism in my clothes. For instance I make my buttons out of the kind of faux sushi you see in the windows of Japanese takeout places. Sometimes I use dice.

I like to amuse myself with my clothes, and I don't really care if anybody else likes them. I made myself a pair of earrings out of typewriter keys. That's one of my favorite things. I love getting dressed, and I just do it for myself.

GROSS: What happened to your mother when the '60s came along, and fashion went crazy, and by the late '60s and early '70s, young people weren't wearing makeup, they were not wearing tailored clothes or sweater sets, no coiffed hair? Your mother's look was always crisp. It was not about being crisp.

VOLK: She maintained her look. She didn't change her look at all. She didn't become less formal, she didn't wear less makeup, she didn't have her hair done any less. That was her look, and she kind of sailed into a room. She looked as if she thought she was terrific, and it's funny when women do that, when they present themselves a certain way, they're perceived that way.

GROSS: Did the women's movement change your idea of yourself as a woman or your mother's idea of herself as a woman?

VOLK: I don't think it changed my mother's, and I certainly was somebody who was active in the woman's movement. I marched for choice. I fought all the time at work for the pay the men were getting. I was kind of enraged, and I was always asking for raises. But I think I would have done that without the woman's movement. It was just out of a tremendous sense of injustice.

GROSS: In talking about Schiaparelli, you know, and the clothes that she designed, one of the things that's so interesting about her as a designer, and you write about this in your book, is how she reinvented women's underwear during World War II. And I'd like you to describe how she did, like, what she did that was so transformative.

VOLK: Well, women's underwear before World War II was kind of elaborate. It was usually made of silk, and it had pleats, and it had to be ironed. This was in France. There was no such thing as drip-dry. And when the war started, most of the men went to the front, and the women had to take jobs, and there was gas rationing.

And so everybody had bicycles, and you had to be licensed to ride a bike in Paris. And in one year, I think it was 1939 or 1940, bike licenses tripled. It went up to 11 million. Well, the way women dressed, with these long skirts and this very elaborate underwear, didn't lend itself to riding a bike. So Schiap changed panties completely.

First of all, there was famine, so she got rid of the buttons and put elastic in the waist so that as you were losing weight, your panties would stay on. Then she made them out of drip-dry material so you didn't need a maid to iron them. So they weren't labor-intensive.

And then she took off a lot of the ruffles and geegaws that were on the underpants, and she added a double-slung crotch. And suddenly women could ride their bikes with a lot more freedom and have a lot more time to work and be at home instead of ironing their underwear.

And she also changed the way she made clothes. She put big pockets in her jackets so that women could load them with - and have their hands free while they were riding the bike. And she made pantaloons that matched the skirts so that when they showed, they looked adorable. And she adjusted with the times. She knew that war changed everything, and in this case it started with the bottom up.

GROSS: I find it so interesting that a designer who was so dedicated to a surrealistic streak in her fashions did something so practical during the war in her designs for women.

VOLK: That is interesting. I mean, she was subversive, but she was also practical. One of her great surreal handbags, which was a collaboration with Salvador Dali, it's just so brilliant and so practical. It's a leather handbag with a tiny battery in it, and on the front there's a recessed lamppost. And when a woman went home, it could light her way home, and it could also show her where to slip her key in the door.

It was just - she liked combining that. She wasn't impractical. But she could be surreal and practical at the same time.

GROSS: If you've just joining us, my guest is Patricia Volk, and she's written a new memoir called "Shocked: My Mother, Schiaparelli and Me." Let's take a short break here, and then we'll talk some more. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: If you've just joining us, my guest is Patricia Volk. She's written a new memoir called "Shocked: My Mother, Schiaparelli and Me." And it's a memoir about her mother, who was very beautiful, and the emphasis that her mother put on beauty and compares that to the designer Elsa Schiaparelli's idea of beauty and of fashion, which was very mixed with this surrealist artistic sense.

So we were talking earlier about your mother's emphasis on beauty and how she was a beauty. She had a facelift when she was, what, around 40?

VOLK: Yes, in her 40s.

GROSS: Which is pretty young, I think, for a facelift.

VOLK: I think it is, too, but, you know, when beauty is the coin of your realm, you do what you need to do to keep looking good.

GROSS: How did it turn out?

VOLK: Well, I think she was initially pleased. She didn't look like my mother to me anymore. She looked to me like a police sketch of my mother. To see my mother's face, the face I loved, I would look in old photo albums. And the facelift got a little bit botched. A nerve was severed. The doctor was supposed to operate on her at 8:30 in the morning, and it kept getting delayed and delayed and delayed.

And they didn't take her down until 6 o'clock in the evening, and I think he must have been working all day. And he severed the nerve that raised the left side of her mouth. But my mother was such an expert at masking it that I didn't know until 40 years later that that had happened. And I don't think my father knew, either.

But when she got very, very sick, and she really had no energy left, I saw the droop, and she told me what had happened.

GROSS: Where you shocked?

VOLK: I was shocked, yes I was. I was shocked, and I felt terrible for her, just terrible.

GROSS: What a secret to carry around, and I think about how much effort it must have taken her to compensate for that.

VOLK: It must have taken an enormous effort and a daily effort, whenever she was with people. But I think that being perceived as a beauty was worth the effort to her. Even when she was very old, even when she was in her 80s, she was a beautiful 80s, and people would always continue to say your mother is beautiful. They no longer called her the most beautiful woman in the world, which was - you know, I heard that for 20 years.

But by the time she hit her 50s, she was no longer the most beautiful woman in the world.

GROSS: I wonder, like, if you have to do that much work to, say, cover up the nerve that was severed and to, you know, like put on so much makeup, that if you feel inauthentic underneath it all, that, you know, that the self that you're presenting to the world is somehow inauthentic and that your authentic self is something you dare not show anybody.

VOLK: I would feel that way, but I don't think my mother felt that way. I think she felt she was emphasizing her beauty and presenting something marvelous to the world. I don't think my mother had recognized any bad feelings that she had about herself. She thought everything she had was the best, from her towels to her dentist to sometimes her daughters, definitely her husband.

GROSS: I like the way you say sometimes her daughters.

(LAUGHTER)

VOLK: We were capable of disappointing her, but to the public all she did was rave about us. On the other hand if she took me shopping, and she didn't like the way I looked, and she ran into a friend, she would kind of turn her back as if I was just another shopper and not introduce me, if I wasn't having what she considered a good day. And, you know, that made me feel sorry for her. I can't imagine doing that with my children.

GROSS: Patricia Volk will be back in the second half of the show. Her new memoir is called "Shocked." You can read an excerpt on our website, freshair.npr.org. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross back with Patricia Volk, author of "Shocked," a mother-daughter memoir that reflects on two opposing views of womanhood. The one Volk's beautiful, stylish, but conventional mother presented, and the one Volk read about in the autobiography of the iconic classic fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli.

You have an earlier memoir called "Stuffed" and it's about growing up in a restaurant family. And your family owned a restaurant on West 38th Street in Manhattan in the garment center in the area where the fashion industry and the schmatta business...

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: ...was. So I want you to describe your family restaurant.

VOLK: Well, I think it sat around 300 people. The walls were wood paneled. It was the center of the garment center. It's where all the buyers and the manufacturers came with gorgeous models on their arms and big cigars. And at lunch my mother manned the velvet rope and she was always dressed to the nines. And the food was terrific. The menu was what was then called continental - which means it had dishes from all over the world. A chef wasn't known for a single specialty then. He was known for his ability to have a broad menu - like Islander shrimp blue and duck a l'orange. He'd have to cook Getulte Rinderbrust with that. And the people loved of food and they loved the ambience.

My father set a hard party rhythm, and he was on his feet and he knew all his customers and he had a joke for them and he was kind of the Toots Shor of the garment center. And there was my beautiful mother working the line and she was an expert at getting people up from the tables so she could have another seating. And, in fact, at lunch they had three seatings. It was so packed. The line would go out the door. And in the evening they would get the business from the old Madison Square Garden and Broadway. And there was a hat - two beautiful hat-check girls and they would sell Choward's Violets - this very strange candy that if you drank too much you could suck it and no one would know, and it tasted like flowers. They were purple and they came in this wonderful aluminum wrap. And my father was at the center of it all.

GROSS: What was your mother's trick to getting people up out of the tables so that she could get another seating?

VOLK: She'd come over to the table with an armload of menus and say, did you enjoy your lunch? And then she'd whisk their coffee cup away.

(LAUGHTER)

VOLK: Or she'd say, thank you so much for coming. How did you enjoy your dessert? You know, and then the coffee cup would disappear and she'd say, Gus, bring the check over to nine. And, you know, suddenly people found themselves standing up.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: So I think it was your great uncle who brought pastrami to America?

VOLK: Actually, that was my great-grandfather, Sussman Volk. My father was called Cecil but his real name was Sussman. And Sussman Volk came to the Lower East Side in 1887, and he had been a miller in Vilna, but New York didn't need millers at that time, so he became a tinker, and he walked around with pots and pans on his back and sharpened knives and he felt that the life lacked dignity. He was a very religious man. So being a religious man, being an Orthodox Jew, he knew how to butcher meat and he opened a tiny, tiny butcher store at 88 and a half Delancey Street. And one day a man came in from Romania and asked if he could store a trunk in the basement. He was actually going back to Romania. He must've been the only refugee who went back. But he was going back and Rab Sussell, as he was called, because he was a religious man said yes, you can store your trunk in my basement, but what will you give me?

And the man said I'll give you the recipe for pastrami. So my great-grandfather started curing pastrami and then people wanted it on a slice of bread, and then he put chairs and tables in and suddenly it was a delicatessen. And after school, all his five children came into the store and made toodles(ph), which were little cones of waxed paper with a dollop of mustard in them that people could squeeze onto their sandwiches. He was the first pastrami vendor in New York. The following year, Katz's opened. But Sussman Volk was the first delicatessen.

GROSS: So what is the recipe for pastrami? How do you make it?

VOLK: Well, it's a step beyond corned beef. Pretend you're making corned beef and then dry the meat. Press all these wonderful spices in it and dry smoke it, and you'll have pastrami. And pastrami, we make it with beef, but pastrami is a way to preserve meat. Pastrami is actually a verb; you pastrami something to preserve it. You could do it with fish. It was done with camel long before it was done with beef.

GROSS: So your answer assumed that I know how to make corned beef.

VOLK: Yeah. I think to make corned beef you boil the meat in salted water.

GROSS: I see. OK. Thank you.

VOLK: So that's the first step.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: So your parents were well-known for their restaurant. You had an uncle who was well-known as a demolition man. He knocked down - how many buildings in his career?

VOLK: Oh my god. Hundreds. Jacob Volk was my paternal grandfather. He invented the wrecking ball and he...

GROSS: He invented the wrecking ball?

VOLK: Yeah. And he invented the upside-down method of house wrecking - which was knocking the roof out and then taking the building down inside with these huge, huge, sort of, tubes and having trucks lined up that he would fill. They'd go directly into the truck. And he was a Jew and Jews were not welcomed in demolition and shoring at the time he went into it, which was in the early 1900s. But he broke into the business by saying, I will pay you for the right to tear down your building, and then he resold all the pieces. And he had Klondikers - men who would chip old cement off bricks for five cents a brick. He resold every break.

I think they were called Klondikers because they went to the Klondike and then they came back, they weren't successful. And there were legions of them. Eventually, he did get paid for taking down buildings because he was so good at it. And he had time clauses in his contracts and if he tore the buildings down before the date that they were supposed to come down, he'd get a huge bonus at that time. He was a very rich man. He won the land for his house that he built in Bensonhurst in a card game with Jimmy Walker. He was a high liver, big drinker and a fair man. He paid his men every week on time and what they were promised, but he kept a blackjack on his desk and a bottle of liquor and he gave them the money and a shot, and they looked at the blackjack and they were happy.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Patricia Volk, thank you so much for talking with us.

VOLK: Thank you, Terry.

GROSS: Patricia Volk's new memoir is called "Shocked." Her earlier memoir about her restaurant family is called "Stuffed."

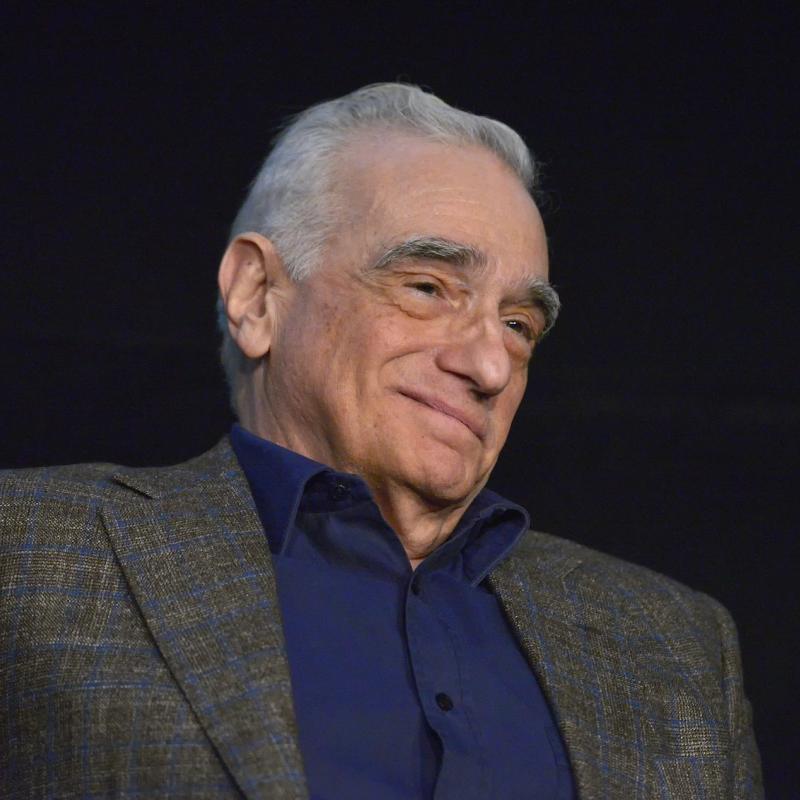

Coming up, Martin Scorsese talks about the very early days of cinema. We hear an excerpt of his National Endowment for the Humanities Jefferson lecture - which he gave last month.

This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

TERRY GROSS, HOST: Martin Scorsese is a great director, but after having heard him talk several times about movie history and his favorite films, I've come to also think of him as a great film teacher. We're going to hear him talk about the early days of cinema. One of the early film directors, Georges Melies, was the inspiration for Scorsese's movie "Hugo."

We're happy to be able to present an excerpt of Scorsese's talk when he gave the National Endowment for the Humanities' 42nd annual Jefferson Lecture last month at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. He started his talk with a clip from the film "The Magic Box," which was made in 1950. When Scorsese saw it, in 1952, it made a lasting impression on him. It's based on the story of William Friese-Greene, who invented the movie camera, and stars Robert Donat. In this scene, Friese-Greene has just projected moving images of London's Hyde Park for a man who's never seen a moving picture before and is astonished by what he's just witnessed.

(SOUNDBITE OF LECTURE)

(SOUNDBITE OF MOVIE, "THE MAGIC BOX")

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: Where's it come from and where is it going to?

ROBERT DONAT: (as William Friese-Greene) It's all here. Here. Look. That's where the Hyde Park you saw is. Like a magical lantern.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: But it moved.

DONAT: Yes, it moved, didn't it? Now look, look at this strip of celluloid film.

It took me years to get to that - years.

That's the secret. Dozens of snapshots of Hyde Park - only in one picture, the carriage is here, the next it's here, the next it's here, the next it's here - and so on. Now look at the negatives. You see, the film - that's what it's called - comes from this spool over these rollers - that's the tension; you've got to have tension - onto this second spool down here. Now look in the middle. It's a bit like a magic lantern, but instead of one picture at a time, you see eight or more pictures every second - and that's what you see in that sheet there - eight pictures every second, and they all merge together into one moving, living picture. See?

Of course, there's a bit more to it than that. I'm not saying it's perfect - far from it. But it works. God be praised, it works, doesn't it? You can see that.

(SOUNDBITE OF APPLAUSE)

MARTIN SCORSESE: Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. This scene is from a picture called The Magic Box," which was made in England in 1950. And the great English actor Robert Donat plays the inventor William Friese-Greene - he was one of the people who invented movies. I saw this picture for the first time with my father. I was eight years old. And I have never really gotten over the impact that it had. And I believe this is what ignited in me the wonder of cinema, and the obsession - watching movies, making them, inventing them.

Friese-Greene gives everything of himself to the movies, and he dies poor. He dies a pauper. That line - You must be a very happy man, Mr. Friese-Greene - of course, is ironic, knowing the full story of his life. But in some ways it's also true because he's followed his obsession all the way. So it's both disturbing and inspiring.

And then my parents had a good reason for taking me to the movies all the time, because I was always sick with asthma since I was three years old. And I couldn't - apparently couldn't do any sports, or that's what they told me. But really, my mother and father did love the movies. They weren't in the habit of reading, that didn't really exist where I came from, and so we connected through the movies.

And over the years, I know now that the warmth of that connection with my family and with the images up on the screen gave me something very precious. Because we were experiencing something fundamental together. We were living through the emotional truths on the screen together, often in coded form, these films from the '40s and '50s. Sometimes they were expressed in small things - gestures, glances, reactions between the characters, light, shadow. I mean, we experience these things that we normally couldn't discuss or wouldn't discuss, or even acknowledge in our lives.

And that's actually part of the wonder. So whenever I hear people dismiss movies as fantasy and make a hard distinction between film and life, I think to myself that it's just a way of avoiding the power of cinema. And, of course it's not life - it's the invocation of life, it's an ongoing dialogue with life.

Frank Capra said: Film is a disease.

(LAUGHTER)

SCORSESE: He went on, but that's enough for now.

(LAUGHTER)

SCORSESE: I caught the disease early on, you know. I used to feel it. And they used to take me to the movies all the time. I used to feel it whenever we walked up to the ticket booth with my mother, my father, my brother. You'd go through the doors, on the thick carpet, to - past the popcorn stand that had that wonderful smell - then to the ticket taker, and then sometimes they'd get - these doors would open in the back and there were little windows in it in some of the old theaters and I could see something magical happening up there on the screen, something special. And as we entered, for me I think now, it was like entering a sacred space, a kind of a sanctuary where the living world around me seemed to be recreated and played out.

What was it about cinema? What was so special about it? I mean I think I've discovered some of those - some of my own answers to that question a little bit at a time over the years.

First of all, there's light. Light is at the beginning of cinema, of course. It's fundamental - because it's created with light, and it's still best seen projected in dark rooms where it's the only source of light. But light is also at the beginning of everything. Most creation myths start with darkness, and then the real beginning comes with light - which means the creation of forms. Which leads to distinguishing one thing from another, and ourselves from the rest of the world. Recognizing patterns, similarities, differences, naming things - interpreting the world. Metaphors - seeing one thing in light of something else. Becoming enlightened. So light is at the core of who we are and how we understand ourselves.

And then there's movement. I remember when I was about five or six, somehow I was able to see someone project a 16-millimeter cartoon in a small projector, and I was allowed to look inside the projector. And I saw these little still images passing mechanically through the gate at a very, very steady rate of speed.

And at the gate they were upside-down, but they were moving. And on the screen they came out right-side-up, moving. At least there was the sensation of movement.

But it was really more than that. Something clicked then: pieces of time. That's how James Stewart, the great actor, defined movies in a conversation with Peter Bogdanovich. That wonder I felt when I saw this, these little figures move. The desire to make images move, the need to capture movement, I mean, it seems to be with us. Well, 30,000 years ago in the cave paintings at Chauvet, as you can see here.

In this image the bison appears to have multiple sets of legs. Maybe that was the artist's way of creating the impression of movement. I think this need to recreate movement is a mystical urge. It's an attempt to capture the mystery of who and what we are and then to think about that, to contemplate that mystery. Which brings us to the boxing cats.

(LAUGHTER)

SCORSESE: Yes, yes, yes. Yes, these are the boxing cats. This appears to be two cats boxing. It was shot in 1894 in Thomas Edison's Black Maria studio that he had in New Jersey. It was actually a little shack. This is one of, really, hundreds of little scenes that he and his team recorded with his kinetograph. It's probably one of the lesser-known scenes.

(LAUGHTER)

SCORSESE: There are better known ones of a blacksmith, the heavyweight champion Jim Corbett boxing; you know, Annie Oakley, the great sharpshooter from Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. I mean, at some point somebody had the idea that, you know, two cats boxing apparently is what went on in New Jersey at the time.

(LAUGHTER)

SCORSESE: Didn't say anything about now. OK. Edison, of course, was one of the people who invented film and there's been a lot of debate about who really invented film. There was Edison, the Lumiere Brothers in France, Friese-Greene and R.W. Paul in England. And actually, you can go back to a man named Louis Le Prince who shot a little home movie in 1888.

But then you could go back even further to the motion studies of Eadweard Muybridge, which were made in the 1870s, 1880s. He would just set - just, but he would set a number of still cameras side by side and then he'd trigger them, take photos in succession of people and animals in movement. His employer, Leland Stanford, bet him that all four of a horse's hooves do not leave the ground when the horse is running.

But as you can see here, Muybridge won the bet. All four hooves do leave the ground at the same time while the horse is galloping. I mean, does cinema really begin with Muybridge or should we go all the way back to the cave paintings?

In his novel "Joseph and His Brethren" Thomas Mann writes: The deeper we sound, the further down into the lower world of the past we probe and press, the more do we find that the earliest foundations of humanity, its history and culture, reveal themselves unfathomable.

All beginnings are unfathomable. The beginning of human history, the beginning of cinema. Now this film, by the Lumiere Brothers in France is commonly recognized as the first publicly projected film. It was shot in 1895 and when you watch it, it really is 1895; the way they dress, the way they move. It's now, the present, and it's then at the same time. And that's the third aspect of cinema that makes it so uniquely powerful.

It's the element of time. Again, pieces of time. When we made the movie "Hugo" we went back and tried to recreate that first screening when people were so startled to see this image that they jumped back. They thought the train was going to hit them, you see. And when we studied the Lumiere film, because we had to use the original, we could see right away that it was very different from the Edison films.

They weren't - these films that the Lumieres did, they weren't just setting up the camera to record events or scenes. This film is composed. When you study it, you can see how carefully they placed the camera, the thought that went into what was in the frame, what was left out of the frame, the distance between the camera and the train, the height of the camera, the angle of the camera.

And what's interesting is that if the camera had been placed even a little bit differently, the audience probably wouldn't have reacted the way they did. So in essence, the Lumieres weren't just recording events the way they did in the Edison studio, they were really interpreting reality and telling a story with just one angle.

And of course, so was Georges Melies. Melies began as a magician and his pictures were made to be part of his live magic act. He created trick photography, incredible handmade special effects. And in so doing, he sort of remade reality. The screen in his pictures is like opening a magic cabinet of curiosities and wonders.

Now, over the years the Lumiere Brothers and Melies had been consistently portrayed as opposites: one filmed reality, the other filmed special effects. Of course this happens all the time; it's a way of simplifying history. But in essence, they were both heading in the same direction. They were just taking different roads. They were taking reality and interpreting it, reshaping it, and trying to find meaning in it.

GROSS: We're listening to an excerpt of Martin Scorsese's 2013 National Endowment for the Humanities Jefferson Lecture. We'll hear more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: Let's get back to Martin Scorsese talking about the early days of cinema. We're listening to an excerpt of his National Endowment for the Humanities 2013 Jefferson Lecture. In this part he talks about the addition of editing to the early language of film.

(SOUNDBITE OF LECTURE)

SCORSESE: Everything went further, was taken further with the cut. Who made the first cut from one image to another, meaning a shift from one vantage point to another with the viewer understanding that we're still within one continuous action? As far as we know, one of the earliest and most famous examples of a cut is from Edwin S. Porter's 1903 milestone film "The Great Train Robbery."

Now, even though we cut - he cuts from the interior of the car to the exterior, we know we're in one unbroken action. And this film is one of the dozens of one-reel films that D. W. Griffith made in 1912. It's a remarkable film called "The Musketeers of Pig Alley," commonly referred to as the first gangster film, and actually it's a great Lower East Side New York street film.

Now, if you watch, the gangsters are crossing quite a bit of space before they get to Pig Alley. Which is actually a recreation of a famous Jacob Riis photos of "Bandits' Roost" from the Five Points. But you know you're not seeing them cross that space on the screen, yet you are seeing it. You're seeing it all in your mind's eye. You're inferring it.

And this is the fourth aspect of cinema that's so special, that inference, that image in the mind's eye. For me, it's where the obsession began. It's what keeps me going, actually. It never fails to excite me. Because you take one shot, you put it together with another shot, and you experience a third image in your mind's eye that doesn't really exist in those two other images.

The Soviet filmmaker Eisenstein, Sergei Eisenstein, wrote about this and it was at the heart of all the films he did. And this is what fascinates me, though. It's frustrating sometimes, it's always exciting. Because if you change the timing of the cut even slightly by just a few frames or even one frame, then the third image in your mind's eyes changes too. And that has been called - appropriately, I believe - film language.

Now, in 1916, D.W. Griffith made a picture, an epic called "Intolerance" in part as an act of atonement for the racism in "Birth of a Nation." "Intolerance" ran about three hours but he goes further; he goes further with the idea of the cut. He shifts between four different stories.

The first story is the massacre of the Huguenots, and the second story is the Passion of Christ. The third is a spectacle, really: the fall of Babylon. And a fourth story, which was a modern American story set in 1916, the train. Now, at the end of the picture, what Griffith did is that he cut between the different climaxes of these different stories.

He cross-cut through time, something that had never really been done before. He tied together images, not for story purposes or narrative purposes, but to illustrate an idea, a thesis. In this case the thesis was that intolerance has existed throughout the ages and it's always destructive.

Now, Eisenstein later wrote about this kind of editing and gave it a name. He called it intellectual montage. Now, for the writers and commentators who were very, very suspicious of movies because, after all, it did start as a nickelodeon storefront attraction, this was the element that signified film as an art form.

But of course, it already was an art form. That started with Lumiere and Melies and Porter. This was just another logical step in the development of the language of cinema. But the cinema we're talking about here - Edison, the Lumiere Brothers, Melies, Porter all the way through Griffith and all the way through Kubrick - that's really almost gone.

It's been overwhelmed by moving images coming at us all the time and absolutely everywhere. I mean, classical cinema, as it's come to be called, kind of feels now like grand opera of Verdi or Puccini, that period. And we're no longer talking about celluloid. That really is a thing of the past.

Now, for many film lovers this is a great sadness and a sense of loss. I certainly feel it myself. I grew up with celluloid and its particular beauty and its idiosyncrasies. But, you know, cinema has always been tied to technological development and if we spend too much time lamenting what's gone, then we're going to miss the excitement of what's happening now.

I mean, everything's wide open. To some this is a cause for concern, but I think it's an exciting time precisely because we don't know what tomorrow will bring, let alone next week. And we have no choice but to treat all these moving images coming at us as a language. We need to be able to understand what we're seeing and find the tools to sort it all out.

GROSS: We heard an excerpt of Martin Scorsese's National Endowment for the Humanities 2013 Jefferson Lecture, which he gave last month at the Kennedy Center. Our thanks to the NEH and Paula Wasley. We have more on our website. You'll find a link to a video of Scorsese's complete lecture, links to several of the very early films he referred to, and a slideshow of stills from movies that he mentioned. That's at freshair.npr.org.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.