Roger Manley and "Outsider Art."

Artist, writer, folklorist, photographer Roger Manley was the guest curator of two exhibits at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore: "The Tree of Life" (w/a companion catalogue) and "The End is Near!" The museum opened in 1995. Using the Native American tradition of a personal vision quest as it's model for the kind of work it wants to present, the museum is dedicated to showing and promoting the work of self-taught, intuitive artists. (The phone number for AVAM is 410-244-1900). Manley will discuss visionary art. He is now acting curator of the Gallery of Art & Design at North Carolina State University, Raleigh.

Other segments from the episode on February 18, 1998

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: FEBRUARY 18, 1998

Time: 12:00

Tran: 021801np.217

Type: FEATURE

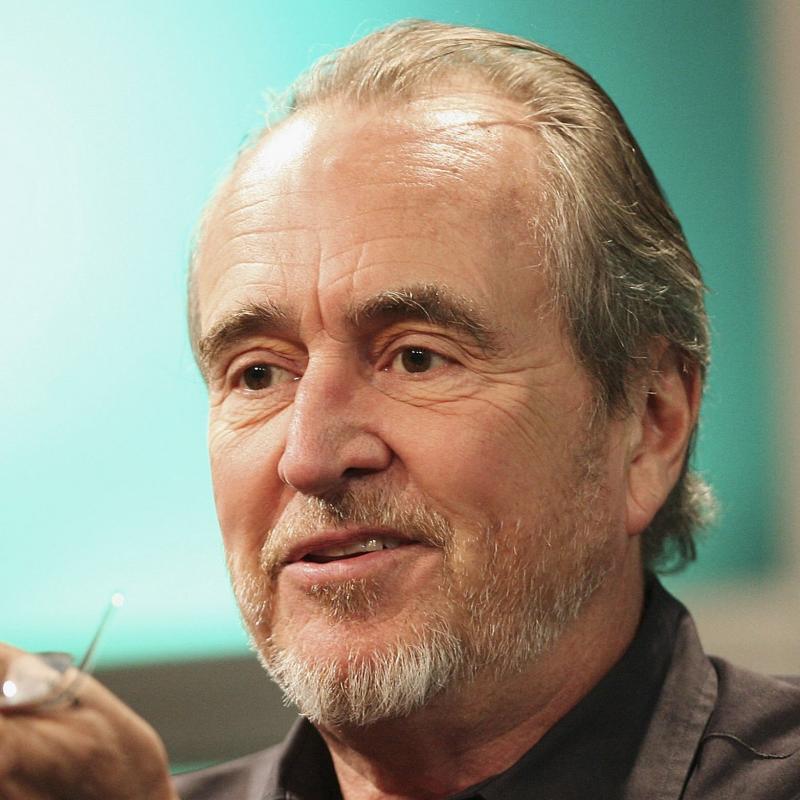

Head: Wes Craven

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:06

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "SCREAM")

SOUNDBITE OF TELEPHONE RINGING

ACTRESS: Tatum, just get in the car.

ACTOR: Hello, Sidney.

ACTRESS: Hi. Who is this?

ACTOR: You tell me.

ACTRESS: Well, I -- I have no idea.

ACTOR: Scary night, isn't it? With the murders and all, it's like right out of a horror movie or something.

ACTRESS: Randy, you gave yourself away. Are you calling from work, 'cause Tatum's on her way over.

ACTOR: Do you like scary movies, Sidney?

ACTRESS: I like that thing you're doing with your voice, Randy. It's sexy.

ACTOR: What's your favorite scary movie?

ACTRESS: Oh, come on. You know I don't watch such (EXPLETIVE DELETED).

ACTOR: Why not? Too scared?

ACTRESS: No, no, it's just what's the point? They're all the same -- some stupid killer stalking some big-breasted girl who can't act, who's always running up the stairs when she should be going out the front door. It's insulting.

ACTOR: Are you alone in the house?

ACTRESS: Randy, that's so unoriginal. I'm disappointed in you.

ACTOR: Maybe that's because I'm not Randy.

ACTRESS: So, who are you?

ACTOR: The question isn't "who am I?" The question is: "where am I?"

ACTRESS: So where are you?

ACTOR: Your front porch.

GROSS: Well, that's how the "Scream" phenomenon started. Scream and its popular sequel "Scream 2," which opened in December, are horror films that also satirize the cliches of the genre. It seems to be a winning combination. Scream grossed $100 million in the U.S. and Scream 2 has already grossed $96-.

The director of both films, Wes Craven, has spent his career creating, subverting, and lampooning the rules of the horror genre. He made his name directing horror films, such as "Nightmare on Elm Street," "Vampire in Brooklyn," "The Hills Have Eyes," and "Last House on the Left." We called Wes Craven and asked him why he thinks Scream's hybrid of horror and satire worked so well.

WES CRAVEN, DIRECTOR, "SCREAM 2": I think the fact was that horror had reached one of its sort of classical, cyclical stages of ennui on the part of the audience. You know, it just had gone so far along the same lines that people were bored with it and kind of knew what to expect.

And it kind of was in that place where it needed to be satirized, at least before you went on and did something new. You had to sort of acknowledge "this is where we've been and I know you're all bored and I know you're thinking you know what's going to happen."

So that became kind of the charm of it. In that sense, it's kind of a release, you know. It's like a joke about anything, and there's kind of a rush of relief that it's being talked about very frankly, you know. So in the sense that you say "we know horror films have been either boring or stupid or predictable" -- that there's kind of a rush of relief because they know at least they're in the presence of somebody who is smart enough to figure that much out. Now, let's see if they can do something new.

GROSS: Tell me what -- what you found most predictable. Your characters have some opinions on that. What -- what's your opinions?

CRAVEN: Well, you know, you could quote some of the characters, you know, the big-breasted girl who runs upstairs instead of out the front door when there's a threat. And you know, who always goes to investigate and you know sort of does the stupid thing, rather than the smart thing; the classic situation of the girl running away from the monastery and always falling down. You know, there's all those cliches in horror films that, you know, we wanted to avoid and also acknowledge -- or stand on their head.

So I think it was -- it was a large part of that; just the sort of stupidity; a sort of a built-in sexism quite often; a sense of gore for gore's sake. And also, a very heavy emphasis on the sort of killer at the expense of any characterization of, you know, of the more normal people, if you will.

And also a complete lack of recognition of the fact that these were events that were happening within the context of a society that had movies about these subjects. You know, people in the movies of this sort had never commented on the fact that they were in a situation very similar to movies that we all know and could easily talk about.

GROSS: Right. And that they could use that knowledge to help them.

LAUGHTER

CRAVEN: Exactly.

GROSS: In the press kit for Scream 2, one of the producers is quoted as saying that she is awed by your ability to evoke terror from the actors you work with. She says: "he can make an actor so terrified that you actually believe these things were happening to that person." What is she referring to?

LAUGHTER

CRAVEN: Well, I -- you know, I don't know exactly. You'd have to ask her. I mean, you know, part of the job is to -- to get that sense of the reality of situations when actors and actresses are surrounded by crew and cameras and not much is really happening, you know, in the actual, physical space they're in.

You know, try to remind them of things that they might have filmed three weeks before in a, you know, totally different environment that will cut immediately either to or from the moment they're in now. So you -- you kind of -- you know, you're kind of their ally in putting them into context of that sort of ephemeral thing which is the movie that's going to be, but is not right at the moment.

You know, it -- that -- that's to me one of the biggest tricks of directing is this trying to -- trying to make them see the movie that isn't done yet or isn't, you know, is hardly begun.

GROSS: 'Cause they're just seeing the moment that they're shooting right now and you want them to see what happened just before and what's about to happen.

CRAVEN: Right. And what's happened to the character and -- and, you know, what it means personally and -- and, you know, what might have frightened her 10 minutes before in the movie that the actress might have completely forgotten about. I mean -- and it's sometimes just -- you know, in conversations with the actor or actress, for instance.

What's the specific example? I'd be working with Drew Barrymore. When she first came on the location, she and I stayed up late one night and just talked about our lives. And from that I learned a lot of personal things.

Her extreme connection to animal threats that I was able to use. So quite often, it was -- when she was reacting to things that are in the script where -- let's say, somebody breaking a window and trying to get at her, it was -- she and I were talking about what was happening to a puppy in a news article about somebody who had tortured a dog.

You know, so's there's all sorts of tricks. You're just trying to find these sort of, you know, the commensurate place in their -- in their subconscious, in their real life, and connect it to the imaginary events in a way that's meaningful to them. And it's different for every single actor and actress.

GROSS: Hmm. Wes Craven is my guest.

I know when I was growing up in the '50s and '60s, "horror film" meant usually a supernatural film -- you know, Frankenstein, Dracula, Wolfman. You're one of the people who made the horror film more about teen anxieties and, you know, slashers who prey on teenagers. Sometimes those slashers are fellow teenagers. Sometimes they're more supernatural-kind of figures, like Freddy Kruger.

So tell me a little bit about how you think the meaning of horror films became transformed?

CRAVEN: Well it -- it's -- I think they're quite profound films. I -- you know, they -- they are dealing with fear, which is certainly one of the primal, primal emotions and one of the most immediate signals of danger and the necessity for taking action or else not surviving. You know, so you can't get much more basic than that.

And I -- and they always sort of perceive, you know, where there's sort of that sub-cutanaceous (ph) subconscious fear that's in the culture at the time. You know, there were lots of films in the '50s about, you know, the effects of atomic energy.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

CRAVEN: There were early on films I think even at the dawning of science about, you know, the effects of science on -- on human conduct, for instance, like Frankenstein, you know, where you have -- it's all based on what can be done medically, you know, to this person. And how -- how that is either in control or not in control.

And there was a long period of sort of psychosis as, you know, sort of the key element of fear because it seemed like there were so many things that had happened in society. I think even post-World War II, where you had culture coming out of the sort of -- you know, coming out of shock of what they had just seen -- of an entire world at war and these sort of horrendous events being perpetrated by, you know, by the Nazis and in a sense by everybody that, you know, went to war against each other.

GROSS: "Psycho" would be a good example of that.

CRAVEN: Psycho was a great example of that, and I wanted to mention that, you know, because that is a pure case of a not a monster in the sense of a, you know, Godzilla or something. But it's -- it's a human monster.

I think, you know, horror films like "Godzilla" and "King Kong" are kind of a relief in a way, because they are so removed from our reality that they're a little bit more of a popular entertainment, although I think in some ways that they speak also to a sort of a subconscious dread that we have botched nature so much or offended it so much that it's going to come back and get us and destroy our cities, you know, because we are, you know, such sort of a carbuncle on the skin of nature, you know.

But certainly with Psycho, you had that -- that idea of the crazy person being the wild card that we -- we would have to deal with even though we didn't want to; that it didn't fit into civilization at all, but simply was -- was there in a significant way.

And that continued on through I think the '70s, you know, where it was psychotic people like "Texas Chainsaw Massacre," where you know, the rural family that had sort of gone back to some primeval state. The Hills Have Eyes was something like that, too.

Then there was -- there was a shift towards almost a mythological-type father figures, with the Michael Meyers (ph) -- "The People Behind The Mask" and Freddie Kruger and then since Jason, too, where they were not really human, but some sort of almost quasi-human killing force, you know, that was completely outside morality.

Also, it's kind of a spin-off, I think, of the psychotic figure. And I think part of the innovation of the Scream series and it's -- you know, it's a sort of a triptic conceived by Kevin Williams and the writer, is that when it really -- when the mask was off, it was not, you know, sort of a mythological creature like a Freddie Kruger, who was almost -- was not really truly human. But it was the kid next door -- your boyfriend.

GROSS: Right. Wes Craven is my guest and he's the director of -- his most recent films are Scream and Scream 2.

In the opening of Scream 2, Jada Pinkett (ph) and Omar Aves (ph) play -- play two people who are going to the movies. They're on a date and they're going to see a horror film called "Stab." And Stab is the film version of the murders that had taken place in their town. And actually, these were the murders depicted in Scream 1.

CRAVEN: Uh-huh.

GROSS: And Jada Pinkett is at this horror film very reluctantly. I mean, she doesn't like horror films. She thinks they're kind of racist, too, because if there's an African-American in it, they're going to get killed off right away. But you know, she -- she doesn't -- she doesn't like these horror films.

And everything that's happening in the theater is really her worst nightmare. There's -- the teenagers are dressed in the masks that the killer wears in the movie. They've obviously seen the movie like dozens of times and they're back again. And they're -- they're kind of chanting in race -- and, you know, there's a lot of bloodlust in the theater.

CRAVEN: Uh-huh.

GROSS: And I'm wondering if you've ever seen strange reactions to your films -- reactions that you might have not been very comfortable with; where -- where the audience is getting more into the bloodlust than in identifying with -- more into identifying with the killer than the victim.

CRAVEN: Right. I'd be a liar if I said I had not been in that situation, because I have. And when I have, it's been very disturbing. And certainly that scene was designed to reflect that, you know.

To the extent that I -- it sort of says to the audience: to the extent that you're enjoying somebody suffering and dying on Scream, you are out of touch with reality. And obviously, that whole scene is, you know, designed to juxtapose a screen death with a natural death within the theater, and the shock of the audience when they finally realize that what they thought was a big publicity joke was an actual murder.

So, there is a condemnation of that reaction to that kind of film at that moment, and I think it's quite shocking. And it was a -- you know, it was a wake-up call in a way. The entire film has that theme running throughout it -- the theme of: do these films encourage, cause, or, you know, such behavior? Or do they, if nothing else, sort of trivialize suffering?

GROSS: My guest is film director Wes Craven. His latest films are Scream and Scream 2. More after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

Director Wes Craven is my guest. And his films include Last House on the Left, The Hills Have Eyes, "Swamp Thing," Nightmare on Elm Street, and his latest films Scream and Scream 2.

Your first film, which was made in 1972, was called Last House on the Left. And in this movie, this is just a really mortifying movie. It's about two girls who are pursued by, you know, a group of, you know, kind of psycho -- I think they're escaped convicts, actually, if I remember correctly. It's sort of a long time ago.

CRAVEN: Yeah, yeah -- and they also have the son along, too.

GROSS: Yeah, and so the girls are raped and then eviscerated by these guys, and it's shown pretty graphically on screen. And then the parents seek to...

CRAVEN: Well, one is.

GROSS: ... yeah, one is -- yeah. And then the parents of the raped and eviscerated girl seek revenge against the killers -- and successfully seek revenge against them in very graphic ways.

CRAVEN: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And I think I might have mentioned to you in an earlier interview that this is perhaps the only movie I ever walked out on because it was so -- the rape and evisceration scenes were so graphic and so upsetting, I didn't want to see it. I didn't want to be in the theater for it. I didn't want these memories to be playing back in my mind.

CRAVEN: Right.

GROSS: I came back after the scene was over. But you know, rarely does a movie upset me like that. What were your reasons then for making it so graphic? And I -- I should say here that the movie was also so cheaply shot, because it was like your first film -- you had no money -- that it plays back like a home movie, which makes it even more disturbing 'cause you can't -- it's harder to say "oh, it's just a Hollywood film"...

CRAVEN: Right.

GROSS: ...'cause it wasn't a Hollywood film.

CRAVEN: No, completely not a Hollywood film. And it was the time of -- Vietnam War was still going full strength, and the notion was to do something that was completely anti-establishment and completely non-Hollywood, and to treat violence as we both felt it really was, and were seeing it played out in -- in, you know, footage, video footage out of the war, which was, you know, it was incredibly personal. It had sexual overtones. It did not cut away. The victims did not often die quickly; that they quite often would beg for mercy.

You know, all of those horribly unpleasant moments in actual violence. And so, that was the -- kind of the, you know, the premise of the movie. It was that it would be completely uncompromising and it would never, you know, the lens would never move away.

We also were -- had both sort of learned the basic skills of filmmaking in a building that was almost exclusively documentary filmmakers who would often talk around, you know, the coffee pot of how they would never look away and they would never interfere if anything they saw, they would just record it.

So that was the -- that was the premise and that's kind of how that was directed. It was, you know -- the scenes were played out almost uncut. But the -- but with the evisceration, which happened to one character, not -- the other one was shot to death, but just for matters of accuracy, it wasn't all about that, but that was the final death.

And that was the moment when the bad guys, if you will, became human because it was -- they became human a moment after they became completely inhuman. And at the moment that they realized they had stabbed this girl so many times that they had -- that they had eviscerated her, in the sense that, you know, there was evidence of the inside of her body on the outside -- that was the point when they realized they had gone completely insane and were in a frenzy.

And they fell away and they tried to wash themselves up at a local lake, and they were completely sickened by what they had done. And to me, that was the important moment because at that moment, the film starts to turn. And the -- these escaped convicts, who were kind of done almost as a burlesque at the beginning and got more and more real, became completely real.

And then the parents, when they became aware of who these people were and what they had done to their daughter and to their daughter's friend, became just as methodical in their revenge killing as the killers had been.

And so it was -- it was kind of an examination of how ordinary people can swing around and become just as, you know, bloody as people who begin as murderers.

GROSS: But you know, in the long-run it finally was being shown as an entertainment. You know, it wasn't being billed as an anti-violence movie that captures the anti-war spirit during this Vietnam era...

CRAVEN: No, but no -- no film will be...

GROSS: ... you know, it's a movie that's gonna play, like, drive-ins and horror theaters and...

CRAVEN: Yeah -- but no film will ever be sold that way.

GROSS: Right.

CRAVEN: And nobody who makes a film has any control over that. All you can do is just control what you put into the film.

GROSS: Yeah.

CRAVEN: Umm.

GROSS: What -- what's the range of reactions that you've gotten to that film over the years? I shared mine. I was out in the hallway for part of it.

CRAVEN: Yeah -- oh no, that was by far the most, you know, extreme reactions I've ever had to a film. They were very, very violently -- many violently angry reactions.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

CRAVEN: I had people get up and leave the dinner table when they learned that I'd made the film. I had people that no longer left their children alone with me. I mean, there was a lot of -- there was a lot of anger, especially on -- from middle class, you know, kind of straight people, if you will.

And there was also an enormous fan reaction of, you know, very positive. So it was very strange. And I also had probably more than ever reactions from guys who said: "oh, that was great." You know, where I sort of felt, oh my God, I don't want to make a movie for you.

GROSS: Right, right, right.

CRAVEN: And I don't think I've ever gone to that place again.

GROSS: Yeah, I was wondering: do you think you could have made a movie like Last House on the Left today, as a filmmaker in your 50s?

CRAVEN: No. I don't think so. There's a -- there's many, many mitigating things that would keep you from doing that. For one thing, just, you know, you're smarter in the sense of where you are in a business and that you have to deal with people and try to do more films. I think that is the sort of film you can only do when you're first starting.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

CRAVEN: It -- I think it hurt me in many ways because it convinced a lot of people that I -- you know, I can only do that and that I must be some sort of a Charles Manson character.

GROSS: Right.

CRAVEN: And also, it was done by two guys who were completely off the radar grid of any sort of censorship. I mean, it was submitted to the MPAA, but at the point that we couldn't get an "R," we simply released it unrated, which is something that you couldn't do once you're a more high-profile director.

So you know, it was -- it's just one of those -- it's one of those films that is...

GROSS: How about just ethically -- ethically, could you have made it today?

CRAVEN: No, ethically -- I -- I don't have any problems with it ethically because I think, you know, it was brutally, brutally honest. I don't know whether I could be quite that brutal again or feel like it was justified doing it more than once. That -- that's what would stop me -- this feeling like I've shown that. Move on to other treatments of violence, but you don't have to be that graphic ever again.

GROSS: Wes Craven. His latest films are Scream and Scream 2. He'll be back in the second half of the show.

I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Back with Wes Craven, director of such horror films as The Last House on the Left, The Hills Have Eyes, A Nightmare on Elm Street, and A Vampire in Brooklyn. His latest films are the box office hits Scream and Scream 2 -- horror films that also satirize the genre.

Now, I know you didn't see many movies as a kid. I think your parents were very religious?

CRAVEN: Right.

GROSS: And what were their fears about movies?

CRAVEN: Well, I think that -- as much as I can put it together, because it was never expressed so much as it just was a fait accompli, when you know, we just didn't go to movies -- was that they were just too worldly, using that term that is used in that fundamentalist world. And that basically, I think, that they were too sexual and too -- I think probably the sexuality of it more than anything else was what disturbed them.

But you know, the fact of the themes and the subjects were too -- too risque, too sexual, too whatever for -- to be of any good to the mind and body, which was considered the tabernacle of the Holy Spirit. So you know, there was -- it was kind of a panoply of things that were not done or allowed, you know -- smoking, drinking, playing cards, dancing. All of those things were -- were forbidden; that simply were not part of my life.

And it wasn't a huge problem for me. I mean, I -- you know, if you're not aware of something, it's simply not there in a way. And I was...

GROSS: Well, where -- where did you grow up? I mean, and how -- how...

CRAVEN: Cleveland, Ohio. It's -- you know, it wasn't like I was living out in the middle of, you know, Holy Roller territory. It was just a fundamentalist Baptist Church and there were a lot of other churches that also believed the same thing. So it was -- you know, at that time -- and I wouldn't be surprised if there are still churches that -- that have those general guidelines. It just was not, you know, something that was done.

And the -- my mother was very, very involved in the church, and the church was virtually the core of our social lives. You know, we went all day Sundays and then Wednesdays for prayer meetings, and church camps and church daily vacation bible schools and everything else. It was -- it was my world until I broke out of it.

So you know, it was just -- I was guided towards books and became a bookworm and, you know, got my -- got my joy of storytelling out of, you know, reading -- reading novels, basically.

GROSS: Do you feel that any of your horror films have addressed your innermost fears?

CRAVEN: Oh, I think they all have. You know, I think there's a great deal in there that -- that has to do with that. And you know, I know that Freddie Kruger -- and this is not to be -- you know, this is the sort of thing that, you know, one's mother in Cleveland can hear by third-hand and be horrified by -- but I think there was -- there's a certain -- a fear that I had for my father, for instance, that comes out in, you know, in a grotesque form in, like, a Freddie Kruger, who is like the ultimate patriarchal nefarious character, you know -- who is dangerous and takes delight in sort of scaring the younger.

That -- not that my father chased me around with a glove full of knives, but it was just like to me he was a scary person. I -- he was not around a great deal and he had a sharp anger, you know, a bad temper. And I remember being quite -- quite afraid of him. I'm sure I translated some of that -- those feelings as a small child into those kinds of characters.

And a lot of my films have to do with sons facing -- for instance, in "Shocker," you know, facing a father who was a killer, and who says basically you're gonna be the same thing.

So you know, I don't think they would be anywhere nearly as -- as strong as they have been if they were not in some way reflecting issues that were, you know, from deep inside myself.

GROSS: Speaking of Freddie Kruger, do you remember how you came up with that image of a glove full of knives?

CRAVEN: It was -- it was a pretty methodical sort of intellectual process. I mean, I was trying to work off of primal and ancient sort of atavistic images and themes, you know, since I figured I was dealing basically with dreams which were some sort of primal theater; you know, some sort of brain theater, if you will -- brain cinema.

I was trying to go back to the very beginnings of everything. So it -- you know, it was the father figure and it was -- the weapon was, you know, what I thought was the epitome of human ability was the hand, you know, the human hand, which is so -- so remarkable and so far advanced from any other animal.

And going back beyond that, the primal threat that I, you know, surmised -- must have faced primitive man was, first of all, edged and pointed weapons of tooth and fang and claw and talon -- and just put that onto the -- attached that to the -- to that extraordinary instrument of good and evil of the human hand.

GROSS: Now, I know Scream and Scream 2 were I think part of a three-picture deal with Miramax, and the agreement was for one of those pictures, you didn't have to do a horror film.

CRAVEN: Uh-huh.

GROSS: Which is, I think, something you've been waiting for for a while -- a chance to do something else.

CRAVEN: Yeah.

GROSS: So tell us about what this other film -- the film that's not a horror film -- is going to be about.

CRAVEN: Well, we -- we have several things in development. The thing with the most heat on it right now is something based on a documentary that was called originally "Fiddlefest" (ph) and then I think was released under the title "Small Wonders." And Small Wonders/Fiddlefest is the story of a woman who teaches -- an actual living woman, Roberta Tavares (ph) -- who teaches classical violin in East Harlem.

And even when she went in, she was told that, you know, these kids would not be capable of learning really classical music. And the results, after 14 years, are that her kids have played at Carnegie Hall and they just -- she and a whole group of her students just returned from Europe, having toured in many of the royal courts and the theaters. And she's a tremendous triumph.

So, it's one of those wonderful stories of -- of a woman who turned her own life around by turning the lives of students around and vice versa.

GROSS: This kind of inspirational movie seems very out of character for you. What appeals to you about the story?

CRAVEN: Well you know, it's just that there's -- it's just huge parts of myself that have not been, you know, put into my movies except in sort of codified ways. So it represents a lot of what I'm interested in, and I love classical music.

I was -- I was a teacher. I taught college humanities for five years. I taught high school for a year. So I love -- I love the -- you know, the realm of teaching and the idea of showing what a really good teacher can do is really exciting. It just has a lot of things about it that I really like.

So it's -- you know, it's -- it's -- it's just one of those things that when you do horror films, people always assume that you have a very limited perspective, but myself and most of the horror film directors that I know are very broadly educated people and have a lot of other things in their life. And it just happens to be that that is what they have become famous for.

GROSS: Your last couple of horror films, Scream and Scream 2, have been so successful. Do you want to use that success to keep making more horror films? Or, would you like to get away from the genre and -- and do only other things now, or mix it up?

CRAVEN: Very much like to mix it up. I mean, I feel like, you know, I've had really an interesting career in that genre, partially from choice, partially from the fact that it was very difficult to get work outside. With the two Screams, I've had a tremendous amount of feedback now from studios and from producers saying, you know, we can see you can do just about anything, because there is comedy in there and there is -- there is real relationships and really great performances.

So we're developing other projects that are, you know, out of the genre. I would like to do "Scream 3" because first of all it was a great challenge doing a sequel that has done as well as the first one -- that rarely, rarely is done.

GROSS: Yes, even your characters know how hard it is to make a good sequel.

CRAVEN: Yeah, it really is. And then, you know, it's now virtually at the same mark that the first one was at. And I can't think of anybody that's done three in a row really, really well. So that's a great challenge.

After that, I wouldn't mind saying good-bye forever to horror. If I could, I think that would be my choice, and just to go on into other -- other sorts of films.

GROSS: Thank you so much for talking with us. I should let you get back to work.

CRAVEN: OK, Terry.

GROSS: Director Wes Craven. His latest films are Scream and Scream 2.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "SCREAM")

ACTOR: Don't you know the rules?

ACTOR: What rules?

ACTOR: You don't...

SOUNDBITE OF BANGING

ACTOR: Jesus Christ, you don't know the rules?

ACTOR: Have an aneurysm, why don't you?

ACTOR: There are certain rules that one must abide by in order to successfully survive a horror movie. For instance, number one: you can never have sex.

SOUNDBITE OF CROWD BOOING/CATCALLS

SOUNDBITE OF BEER BEING POURED

ACTOR: Big no-no. Big no-no.

ACTOR: The date man.

ACTOR: (Unintelligible) impossible. Sex equals death. OK. Number two: you can never drink or do drugs.

SOUNDBITE OF CROWD BOOING/CATCALLS

SOUNDBITE OF BEER BOTTLES CLINKING

ACTOR: No, the sin factor. It's a sin. It's an extension of number one. And number three: never, ever, ever under any circumstances say: "I'll be right back," 'cause you wont' be back.

ACTOR: I'm getting another beer. Do you want one?

ACTOR: Yeah, sure.

ACTOR: I'll be right back.

SOUNDBITE OF CROWD BOOING/CATCALLS

ACTOR: You see, you push the laws, and you end up dead. OK, I'll see you in the kitchen with a knife.

GROSS: We will be right back.

This is FRESH AIR.

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Wes Craven

High: Wes Craven, one of the foremost directors of horror films. His credits include "Last House on the Left," "The Hills Have Eyes," and "Nightmare on Elm Street." His latest film is "Scream 2" the sequel to his 1996 film "Scream." Both are horror films that poke fun at the genre.

Spec: Movie Industry; Horror Films; Wes Craven; Culture; Post-Modernism

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1998 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1998 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Wes Craven

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: FEBRUARY 18, 1998

Time: 12:00

Tran: 021802np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: The End Is Near!

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:40

TERRY GROSS, HOST: My guest Roger Manley writes about and curates shows of visionary art, or as it's also called "outsider art." This is the work of artists outside the art world. Their art isn't intended for museums, but it usually transforms their personal surroundings, filling their homes, taking over their backyards or covering their cars.

Manley is the author of several books about outsider art, and he curated the current show at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore. The show is called "The End is Near!: Visions of Apocalypse, Millennium, and Utopia."

The first outsider artist Manley met was Annie Hooper (ph). He had just started college and he was hitchhiking through North Carolina. The guy who picked him up asked if Manley wanted to come over and see his grandmother's woodcarvings. Manley said yes, expecting to find duck decoys or ash trays. Instead, he found the most amazing thing he'd ever seen.

ROGER MANLEY, ARTIST, WRITER, FOLKLORIST, PHOTOGRAPHER, FORMER GUEST CURATOR, AMERICAN VISIONARY ART MUSEUM, ACTING CURATOR, GALLERY OF ART & DESIGN, NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIVERSITY: I was expecting very normal kinds of things. That was just before Christmas -- I thought I'd buy something for, you know, to give the family and that sort of stuff.

And when we went in, as my eyes got adjusted to the light in there, I suddenly realized that there were thousands and thousands of faces looking back at me. You know, all these figures made of concrete and driftwood and spraypainted gold and silver and purple, and Christmas tinsel dangling around the work. And there were artificial Christmas tree lights aimed at it. It was very strange.

So, I had to go back out there later on and take pictures. And something about those photographs that I took on the second visit out there started to -- when I would show them to people, it would trigger things in their -- in their memories. They would say: "oh, I know somebody like that" -- you know, "I've got a -- a neighbor who's building giant whirligigs out on his farm" or "yeah, that reminds me of my cousin who's -- who's collecting mule dung that looks like presidents of the United States."

LAUGHTER

And this kind of thing. And so I would, you know, start to go visit them and gradually realized that there was a phenomena here; this was some kind of thing going on where all these people were making this stuff out in these very unusual places.

I mean, in the backs of service stations or in their apartments. I mean, they weren't in studios and they weren't in art departments. They were just out there in these, you know, in their tobacco barns and that kind of thing.

GROSS: Tell me, in Annie Hooper's home with the thousands of sculptures, was there any room to -- to walk or to sit, to prepare breakfast -- you know, the kind of ordinary things one does at home?

MANLEY: She had -- she had clearings around -- around certain things that she needed to get to -- the place where her husband sat, the -- there was a clearing around the television set. But throughout much of the house, there were just little pathways about six inches wide and you had to place one foot in front of the other and kind of shuffle through to get from one area to another.

I mean, you really need to sort of see this to understand just how crowded it all was. It's a little hard to -- for a lot of people to imagine without seeing a photograph of it.

GROSS: Is she someone whose art you think connected in some way to a mental illness?

MANLEY: I think Annie's art came out of certain problems that she was having. Mental illness is a -- such a weighted word these days.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

MANLEY: I mean, and it -- and it was even more weighted back then. I mean, and I can think of people in my grandmother's or mother's time period that just the mention that a cousin or something had a problem was -- was something you just didn't talk about.

But -- but I think in Annie's case, she grew up in a very large family, and that's something that -- that I've noticed that some of these other artists doing -- they're typically -- are often born into very large families. But she was surrounded by people most of her childhood. When I saw "large," she had something like 13 or 14 siblings, and then there were about a dozen foster children in the house at any one time, so that there were just lots and lots of people around.

And she married into a huge family. Her husband was one of nine brothers and they all had big families. And then when the -- when the Second World War started, a lot of the males left; a lot of the -- they were living on the Outer Banks. It's a -- remember, this is a string of islands off the coast of North Carolina. A lot of the men left, and their wives went elsewhere to sort of last out the war.

And Annie was suddenly left alone, and didn't cope with it very well; had what I guess you would call a nervous breakdown. And she was -- went into an extreme depression. Her husband came and got her -- came back -- he had gone off to work in the Norfolk Naval Shipyards, and then came back to get her and brought her up to the shipyards and said -- you know, "we'll rent a little house up here, and if you want to take in a few boarders to keep you company during the day, that's fine." So she took in 35 boarders, and you know, completely filled the house with people again.

After the war, when they all left, I think she felt a sense of emptiness that just was overwhelming. And she began to deal with it by making these thousands of figures to take care of that sense of emptiness.

GROSS: Could you give us a general description of what is meant by "outsider" art or "visionary" art or whatever term you prefer?

MANLEY: Well, it's art that is made by people who start off with some sort of inner-compulsion to make something. They're not people who generally attend art school or -- you know, learn to do their art through classes or studying books or anything like that.

The kind of person who becomes this kind of artist tends to be someone who has had a career of one sort of another. It's usually a career or you know, like I say, a work that -- whatever they do for work -- I mean, calling it a "career" sounds a little extreme sometimes.

But it's a job that involves some kind of tangible evidence of their activity during the day. And what I mean by that is like a farmer could look back and see that he had plowed so many fields; and a logger could see that he had cut so many cords of wood; or a textile worker could see that she had made so many towels -- this kind of thing.

And they -- at the end of the day, they can see the actual results of their labors. And then typically, something happens -- the death of a spouse or an industrial accident or illness or early retirement -- they're laid off. Something takes away that -- that sense of self-value they had. I mean, they came to value themselves over a period of years by the amount of -- of stuff they could do.

And then when that's taken away, and they're left feeling idle and looking around and not feeling, you know, that they're -- I mean, they'd lose that sense of self-worth. And something in them -- in a small percentage of people that this happens to -- something in them triggers the need to make something else; to start making things again.

GROSS: My guest is Roger Manley. He curated the current show at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore. We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

If you're just joining us, my guest is Roger Manley. He's a folklorist and curator. He's curated several exhibitions for the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, including their current show The End is Near!, which features art about the end of the millennium and visions of the future, visions of the apocalypse. He's also acting curator of the Gallery of Art & Design at North Carolina State University in Raleigh.

The kind of art that you're dealing with, where people make these, you know, huge whirligigs in their backyard or cover their house in -- in tile or do thousands of sculptures inside. This isn't art that hangs tidily on the wall of a museum. What are some of the dilemmas you're faced with as a curator when you want to show some of this work?

MANLEY: Often, I find myself acting as a liaison between the museum and the artists. And I have to work with the artists to make them understand that the museum is not making a huge profit off of their art of anything like that; that -- and that they'll get it back after the exhibition is over.

Sometimes, that's very funny. A while back, I curated a show for the North Carolina Museum of Art, and they were going to exhibit the work of an artist that lived nearby, named Clyde Jones (ph). Clyde is a -- was a former pulpwood logger and after he had an injury -- he felled a tree on top of himself and was lamed for a while -- began making all these thousands of chainsawed animals and setting them up in his yard.

And we were -- we decided to borrow some of those for this exhibition. And I knew the day that they were planning to go down there and pick up his work, so I went down and stayed with Clyde and tried to keep him calm about the whole experience.

So we were standing out there in the yard, and suddenly this climate-controlled truck from the museum drove up with the -- the trained art handlers in their linen gloves. And Clyde was, you know, just agog at the whole thing. They carefully loaded each piece, wrapped it in bubble wrap, and padded it with styrofoam and placed it in the truck with great care, just like you would handle something from the Parthenon or you know, the Mona Lisa or something like that.

And there was one piece that wouldn't quite fit, toward the end. And they said: "well we'll -- we'll come back tomorrow and pick up that piece." And Clyde said: "oh, no, I'll save you the trouble." And he got out a chainsaw and cut it in half. And he said: "just nail it back together when you get there."

And they -- so -- that was kind of an education for them. I mean, they had to -- the museum people had to learn how to think about this work. You know, it's a different attitude toward art than a lot of -- a lot of trained artists have.

GROSS: In addition to working with visionary art or outsider art, you also co-edited a book of photographs from "Ripley's Believe It Or Not." There are some great photographs in this book, including Joe Lorello (ph), the man who could turn his head 360 degrees; and Lydia McPherson (ph) who had the longest red hair in the world; and "Singly" the fire-proof Hindu; and the Great Ohmi (ph), the world's most heavily-tattooed person; Joe Horowitz, who was billed as the man with the iron nose because he could balance an 18-pound saber on his nose; Leo Congi (ph), the "painless wonder" -- I love this guy -- who could drive 60 penny nails into his nose and stick hatpins into his body without discomfort -- and he held his socks up with tacks driven into his legs.

LAUGHTER

Do you see any connection between the art that you're dealing with and the very obsessive people who ended up in Ripley's?

MANLEY: A lot of outsider or visionary art is a way of calling attention to oneself. And -- and feeling special and feeling like you can do something -- you know, feeling unique, like you can do something that no one else can do. And with -- with the outsider or visionary artist, that comes out as art.

For the people in the Ripley's collection, it comes out as a sort of performance or -- or the discovery of some particular kind of talent, whether you can roll your tongue completely sideways one way or the other; or you know, you can stand to stick your hand into a vat of molten lead or whatever.

You know, you realize that you can do something that not too many people are willing to do. And that's -- that's attention-getting and it makes you feel special and that kind of thing.

GROSS: I -- I think, too, that these -- that both of them are people who are absolutely obsessive about doing something that a lot of the outside world would think of as illogical or pointless. You know, whether it's holding your socks up with nails or building zillions of whirligigs in your backyard.

MANLEY: Yeah, but you know, I think these people -- it -- they're really important because how dull a world it would be if we were all just doing the same thing.

GROSS: Like you and me.

LAUGHTER

MANLEY: Yeah, you know, getting up, going to work. Really, you know, I mean, I -- when I -- when I think about peak moments in my childhood, I'm -- I don't think about all of the hours and hours I sat in classrooms of the -- or the, you know, all the times that I went to church or whatever. I think about passing the self-kicking machine on the way to the beach or, you know, seeing the Watts Towers as I went to see my grandmother and that kind of thing. She lived in Los Angeles.

And you know, those are the -- the kind of peak moments that stand out. And I think they do for a lot of people. I mean, I think people will far recall -- are far more likely to recall every visit they ever had to a circus than they are to recall every classroom they ever sat in or, you know, every news program they saw.

GROSS: You mentioned the "self-kicking" machine you used to pass as a boy.

MANLEY: Yeah.

GROSS: What was that?

MANLEY: This was a machine that you stood at a crank, and it was just -- it was just beside the road. There was no one around. There was no -- you didn't have to pay admission or anything. It was just a machine. It just sat there next to the highway.

And you would -- you would step up to it and turn a crank and there was a series of four boots that were on a revolving wheel. And the wheel would kind of come up behind you and it would kick you. And you know, it was up to you to decide how many times you wanted to be kicked.

It was a very strange thing, and it was the -- part of the -- part of the fun of it was the -- the total irrationality of it. I mean, why would you want to stand and kick yourself? But it -- you know, the fact that it was so unusual and seemed to serve no purpose other than just to exist and to give you something to think about, was -- was, you know, was all its charm. And I thought that was fabulous.

GROSS: Well Roger Manley, I want to thank you a lot for talking with us.

MANLEY: Thank you.

GROSS: Roger Manley is the acting curator of the Gallery of Art & Design at North Carolina State University. He curated The End is Near! show which will be at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore through April 12. His books include "Self-Made Worlds: Visionary Folk Art Environments."

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Roger Manley

High: Artist, writer, folklorist, photographer Roger Manley was the guest curator of two exhibits at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore: "The Tree of Life" and "The End is Near!" The museum opened in 1995. Using the Native American tradition of a personal vision quest as its model for the kind of work it wants to present, the museum is dedicated to showing and promoting the work of self-taught, intuitive artists. Manley will discuss visionary art. He is now acting curator of the Gallery of Art & Design at North Carolina State University, Raleigh.

Spec: Culture; Cities; Baltimore; American Visionary Art Museum; Rebecca Hoffberger; Health and Medicine; Mental Illness

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1998 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1998 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Visionary Curator

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.