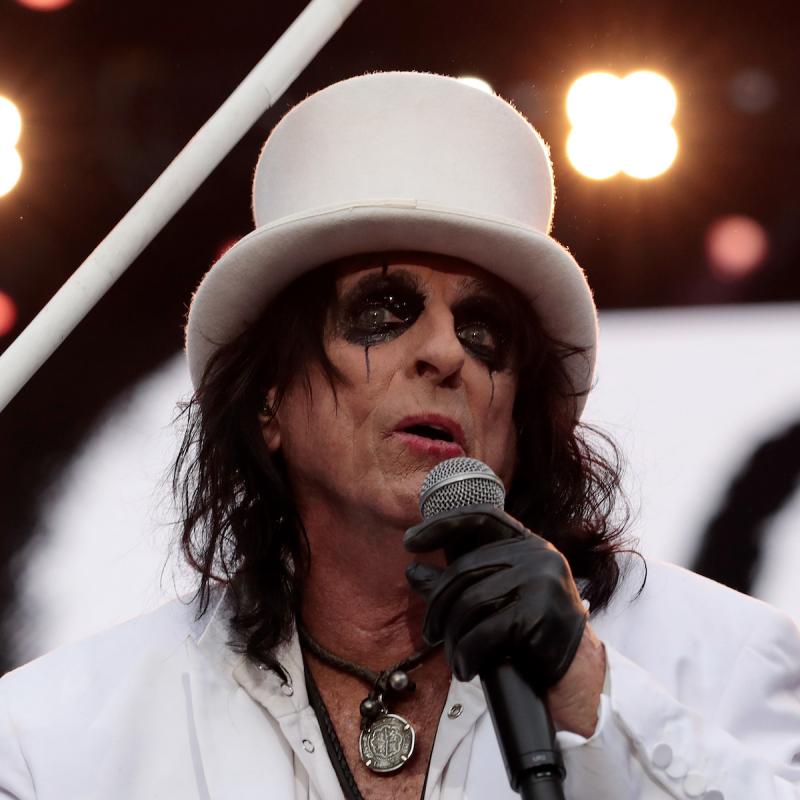

Rocker Alice Cooper, 'Golf Monster'

During his heyday in the early 1970s, shock-rock icon Alice Cooper dressed like a ghoul with a gaunt face and mascara-streaked eyes. His hits included "I'm Eighteen," "School's Out" and "Welcome to My Nightmare." In a memoir — Alice Cooper: Golf Monster, he recounts how he used his obsession with golf to overcome his addiction to alcohol.

This interview was originally broadcast on May 17, 2007.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Transcript

DATE September 3, 2007 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Alice Cooper, author of the memoir "Alice Cooper: Golf

Monster," on the creation of the Alice Cooper persona, his early

stage shows, his Christianity, and his vaudevillian humor

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

We're concluding our series on hard rock and heavy metal with a performer

whose name thrilled teenagers and scared parents in the '70s, Alice Cooper.

His brand of shock rock concerts was about breaking taboos and being decadent.

He wore makeup, black lingerie and a boa constrictor. He took a hatchet to

female mannequins and spit into the audience. He often ended his performances

in a guillotine.

As intentionally crude as the show was, some of the songs were really catchy.

A few of them became big hits like "I'm Eighteen," "School's Out" and "No More

Mr. Nice Guy." Lots of bands have since copied Cooper's look and theatrics.

I spoke with him last spring after the publication of his memoir in which he

confessed he was addicted to golf. The book is called "Golf Monster."

We're going to talk about how he transformed himself from Vincent Furnier into

Alice Cooper. Let's start with this 1972 Alice Cooper anthem.

(Soundbite of "School's Out")

Mr. ALICE COOPER: (Singing) Well, we got no choice,

All the girls and boys

Making all that noise

'Cause they found new toys

Well, we can't salute you,

Can't find a flag

If that don't suit you,

That's a drag

School's out

For summer

School's out

Forever

School's been blown to pieces

No more pencils,

No more books,

No more teachers' dirty looks

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Alice Cooper, welcome to FRESH AIR. Alice Cooper--I mean, the act,

the Alice Cooper act is, it's theater. I mean, it's not just a concert, it's

theater. It's a whole persona and, you know, there's like special effects,

there's a snake. I mean, there's, you know, over the years you've done, you

know, crude things with mannequins, Alice gets executed at the end. Why did

you want to do rock as theater as opposed to just like doing straight concerts

like most people were doing at that time?

Mr. COOPER: That's exactly it, right? Just what you said. The idea of just

doing a straight concert with no fun in it. You know, I mean, rock 'n' roll,

the most theatrical music in the world, and nobody was doing anything. I

would look at bands that I really admired like The Who and The Yardbirds, the

Rolling Stones, and their theatrics were built in to the character. You know,

they had--like Pete Townshend was very theatrical. Mick Jagger was very

theatrical. But I looked at the whole stage--and you have to remember, the

original band were all art students--and we looked at that, and I said, `Why

aren't they painting that canvas?' You've got this entire stage up there, and

nobody's doing anything with it.

I also looked around and I said, `Rock 'n' roll is full of Peter Pans.

Where's Captain Hook? And I will gladly be Captain Hook.' I always thought

the villain always got the best lines. The villain was always the one that

everybody kind of really wanted to see. And so I created this Alice Cooper

character to be all of those villains wrapped up into one, you know, with this

certain amount of tongue in cheek. I definitely--you can't do horror without

having a punchline. I think you need to make the audience laugh. If you

scare them, you need to make them laugh at the same time.

GROSS: Was there as much tongue in cheek at the start as there is now?

Mr. COOPER: Not as much, even though actually, probably, on the "Spinal Tap"

level there was, you know? When things went wrong and you were trying to be

so serious up there, but we--no, I think there was always a sense of humor

involved. I mean, for one thing is that all of the bands--even the bands, all

of the rock press, all had this opinion that if you did theatrics you weren't

a very good band. Because nobody'd ever done it. And if we had a 10-hour

rehearsal schedule, nine hours of that was rehearsing music, because we

realized we had to make the cake before we could put the icing on it. And

then we would spend the other hour on, `How are we going to make this thing

look good?' Well, if it's "Ballad of Dwight Fry," he should be in a

straightjacket. There should be a cold, white light over him. He should be,

you know, the audience should feel the claustrophobia. When he breaks out,

well, there's the nurse that put him in it, and she's a Nurse Ratchet; he

should like strangle her, and of course, then they put--take him to the

gallows and they hang him, and then he comes back out in white top hat and

tails, "School's Out" and balloons, Busby Berkeley.

You know, to me, nobody had done anything, so it was wide open, and nobody was

there to say, `Well, you can't do that.'

GROSS: There's been so many stories over the years about how you created the

Alice Cooper persona. I'd love to hear you tell the story.

Mr. COOPER: Well, I honestly think that it was a combination of two or three

things. There was a moment there where I thought, `Somebody needs to upset

the apple cart a little bit.' We were a good rock band, we lived with the Pink

Floyd and, you know, we were, you know, playing gigs with The Doors and The

Mothers of Invention and all that. Nobody would record us. Finally, Frank

Zappa did record us and, you know, put us on Warner Brothers. But there was

that moment of saying, `We're frustrated. We better do something that's going

to get a lot of attention.' That's when Alice was created.

That's when I said, `Let's create this character that every parent in the

world is going to hate.' You know? Alice Cooper. It's a guy. It's a band of

guys. We're wearing makeup. We're wearing our girlfriends' lingerie, only

we've got black leather pants on and codpieces, and we have cane. We're more

"Clockwork Orange" than "Clockwork Orange." We were as dangerous--and we

didn't mind a little bit of violence up there. We borrowed a little bit of

"West Side Story." This was 1970, when people were easily shocked. I always

said that we were the band that drove the stake through the heart of the love

generation, you know? We were the next thing.

GROSS: Well--yeah.

Mr. COOPER: And so it was so easy to shock the audience, whereas now it's

impossible, you know?

GROSS: It's interesting that you thought your ticket was coming up with an

act that parents would hate.

Mr. COOPER: Well, yeah, that's what rock 'n' roll...

GROSS: Why were you thinking about parents instead of thinking about the

actual audience?

Mr. COOPER: Because the audience were going to go with whatever their

parents hated. If we presented this character, and every parent looked at

Alice and said, `Oh, no, you're not going to be that.' Now, the funny thing

was was this: there was no bad language, I never allowed any bad language;

there was no nudity; there was nothing un-Christian. There was nothing--we

stayed in the boundaries. But that made it even more irritating, I think, to

the general public, that they couldn't really ban us because there was nothing

to ban. You know, I would bring up the point, `How can you ban us and then

let your kids read "Macbeth"?' There's much more blood and Satanic stuff going

on in Shakespeare than ever in Alice Cooper, and yet that's required reading.

So they did have to like look at that and say, `Well, you're right.' I said,

`So it's obviously, you know, against rock 'n' roll. You don't like the idea

of rock 'n' roll.'

But the thing about it was, I looked at "Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?" You

know, Bette Davis. And I looked at that old lady with that caked makeup on

and sort of those black, smeared-on eyeliner?

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: And I said, `That's truly frightening. That, to me, is scary.'

And then we saw "Barbarella." And we saw--Anita Pallenberg played the black

queen. And I said, `That's what Alice should look like right there.' And, you

know, and all the guys were all straight, you know, nobody was gay. But we

had no problem, you know, wearing a piece of women's clothing.

GROSS: Dressing in things like, what, like leather corsets and wearing makeup

and...

Mr. COOPER: Well, yeah, sure. I wouldn't have any problem with that, as

long as, you know--I mean, I was very secure with my manhood.

GROSS: Do you...

Mr. COOPER: First of all, girls loved it.

GROSS: They did?

Mr. COOPER: The girls--oh, yeah, are you kidding? Because everybody was,

you know, Neil Young and Stephen Stills, and everybody was this, you know,

hippie-hippie kind of look, and all of a sudden, here was this band of guys

that were kind of like androgynous--and this was pre-Bowie.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: This was pre-T-Rex. This was pre-, you know, everybody. All of

a sudden there was this band of guys that played really aggressive rock 'n'

roll and liked to fight. And it was just weird. It was just like this

American Frankenstein in your face, you know?

Lot of fun, though. Because, I mean, the controversy was amazing. The urban

legends at the time was half of the charm of Alice Cooper.

GROSS: Now...

Mr. COOPER: Every city I'd go to I'd hear some new story about me, you know?

GROSS: Did you see yourself at the time as having like a sexually androgynous

or ambiguous image? I mean, because you guys were so straight, and it was

such a kind of like macho way of dressing in maybe women's undergarments or

whatever you were wearing onstage for each concert. Do you know what I mean?

But you didn't look like you were gay...

Mr. COOPER: No.

GROSS: ...or like you were trying to be sexually or gender-ambiguous at all.

It looked like a real--yeah.

Mr. COOPER: But, you have to remember, at that time, if your name is Alice

Cooper and you're wearing a great big boa, you know?

GROSS: Right.

Mr. COOPER: And you're wearing tight, black leather jeans and boots and a

switchblade and your girlfriend's slip top that's all cut up with blood all

over it and black leather gloves, and--this is 1968, '69.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: People are going, `Oh no. My son's not going to--that's not

going to be my'--and so when they walked into their room and that poster was

in their son's room? Why do you think that poster was in there? Because Mom

and Dad hated it so much.

GROSS: What did your mother and father think of the act?

Mr. COOPER: Now, my dad was a pastor. And my dad--I grew up in a Christian

church, you know, Christian background. But I was an artist, now, you have to

remember, I was a big Salvador Dali fan. And my dad and mom both knew my

sense of humor. They knew I didn't drink. They knew I didn't take drugs.

They knew I was straight as an arrow. In fact, you know, quite enjoyed the

ladies. And I was an athlete. And I was pretty well versed in the Bible. So

when they saw this character--and I explained to them, I said, `Mom, I said

this is fun.' I said, `Trust me. The fact that everybody is so outraged over

this, it makes it even more fun to do.'

You know, and my dad got the sense of humor in it. Now, my dad was a pastor.

He says, `I love the music.' He said, `I can't buy into the lifestyle. I

can't buy into the drugs and the free love thing, because, you know, I don't

believe in that.' He says, `But the music I love, and the show,' he says, `I

think is very funny.' So my dad was a very cool guy. He got it.

GROSS: I should say...

Mr. COOPER: But he got a lot of flak--yeah, my dad caught a lot of flak.

GROSS: You know, I should mention that you said your father knew that you

didn't drink or do drugs, but that changed because eventually you did plenty

of that.

Mr. COOPER: Oh, yeah, once I moved out, when I got older. Yeah, when I got

older and I got even more far away and more involved in the career, you know,

I--nobody--when you start being in a band, you always go, `OK, oh, man, I want

to have a big, big mansion and I want to have all kinds of, you know,

Ferraris, and I want to have a, you know, this trophy girlfriend, and I want

to be an alcoholic, and I want to be'--no, you don't want to be an alcoholic.

You don't want to be a drug addict. You never see that part coming.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: That part sideswipes you. Because you start out having a beer

with the guys, and then you have another beer because you got to get on the

airplane. And then, you know, it's a two-hour flight, so you're going to have

a couple beers on the plane. You get in town, you got three interviews.

`Well, I'll have a couple beers and do the interviews.' And then there's the

show, got to have a couple beers there. Pretty soon you're doing a case of

beer a day. And that beer now is not beer anymore, it's medicine. And that's

when you're an alcoholic, is when alcohol becomes medicine.

GROSS: My guest is Alice Cooper. More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is Alice Cooper. Here's his 1973 track "Hello, Hooray."

(Soundbite of "Hello Hooray")

Mr. COOPER: (Singing) Hello! Hooray!

Let the show begin

I've been ready

Hello! Hooray!

Let the lights grow dim

I've been ready

Ready as this audience

That's come into the dream

Loving every second,

Every movement, every scream

I've been waiting so long to sing my song!

And I've been waiting so long for this thing to come!

Hey, I've been thinking so long I was the only one!

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: There are so many stories about how you named yourself Alice Cooper.

Which is the real story?

Mr. COOPER: You know, it was--I wish it more theatrical than it is, but we

were sitting around, and we're talking about, `What could we name ourselves?'

Now, the obvious thing is, you know, some horrific name, you know? "Venom" or

something like that. You know, "Husky Baby Sandwich" or something, you know?

And we're sitting there, and I went, "Alice Cooper." And it was the first name

that came out. I said, `What if it was like a little old lady's name? A

little old librarian?' You know? But this little old librarian is like a

serial killer, you know? Nobody ever suspects her. It sounds like a little

girl, Alice Cooper, a little sweet little girl, and they get us. And we all

kind of liked that idea, the fact that nobody would see us coming. They

would, you know--in fact, my wife, when she auditioned to be in the show as a

ballerina, they said, `OK, this is for Alice Cooper,' and she said, `Who's

she?' You know.

You know, I mean, we sounded like a blond folk singer. Some little blond folk

singer from, you know, Pasadena. And what we were were, I mean, we were

actually pre-"Clockwork Orange," and "Clockwork Orange" borrowed an awful lot

of Alice Cooper: the codpieces, the canes, the snakes, the makeup, the guy's

name was Alex, not Alice.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: There was a ton of Alice Cooper in "Clockwork Orange."

GROSS: Now, you mention in your memoir that as a kid, you know, you were an

athlete, you wrote for the high school paper, you were pretty popular, you

were cool, but you couldn't fight. So when you were onstage and you were

being, like, the scary villain character, the horror character, did that kind

of make up for not being able to fight when you were a kid?

Mr. COOPER: Yeah. Oh, no, I created a character that had no problem with

fighting, you know?

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: I created a character that almost went beyond fighting. This

guy was like--he was Bela Lugosi and, you know, every horrific character you

could imagine. I wanted Alice, when the lights came up and Alice was there,

for the audience to go, a collective--(gasps)--that's what I wanted out of

Alice.

GROSS: Was there any kind of compensatory aspect to it because you couldn't

fight as a kid, but here you were being this like scary guy?

Mr. COOPER: Well, you know, the funny thing was, though, it wasn't that I

couldn't fight, it was the fact that--in fact, I was from Detroit, where you

better--I got in a lot of fights when I was a little kid in Detroit. And then

when we moved back to Detroit--again, back to the toughest neighborhoods in

the world--it wasn't that I couldn't fight, it's just that I was the great

diplomat. I was the dark side to Ferris Bueller. I could talk my way out of

a sunburn, you know? And I was always good at talking my way out of it, you

know? I always said, `Why would you want to beat up me? I weigh 100 pounds.'

You know, the guy who was going to beat me up, and I'd go, `I'll tell you

what. Name me a girl in this school, and I'll get you a date with her.' And

the guy was like...

GROSS: Could you do that? Could you deliver?

Mr. COOPER: Oh, absolutely. The girls loved us, you know?

GROSS: How would you do it? How would you get the date?

Mr. COOPER: I was just a charmer...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: I was an absolute charmer. I'd go to the girl and I'd go, `Hey,

look,' you know, `you're the best looking girl in school. I mean, everybody

knows that, and this guy over here's going to kill me if you don't do this,

you know. Could you just do me a favor and go out and with this guy, and,

honestly, I'll owe you a big favor after this.'

Now, you have to remember now, in high school, we were the biggest band in

Phoenix. We played at the best club in Phoenix, and we had a record on the

charts when we were in high school. We owned that school. We owned

everything about it. And, on top of it, we were athletes. We were four-year

letter men. We had the jocks covered, we had the, you know, we had

the--everybody out there. Honestly, nobody could beat me up because I was in

the letter man's club. They'd get killed by the football team. You couldn't

beat up a letter man, you know? So, I mean, honestly, we had that school so

wired, it was unbelievable.

GROSS: I find it so kind of amusing that you're so like easy to talk to, and

you are such a charmer, and how different that it is from the Alice Cooper

stage image.

Mr. COOPER: Well, the Alice character has never, ever talked to the

audience. I mean, when I created this character, I said, `Well, what would he

do? What wouldn't he do?' You know, you have to remember, now, Alice is my

favorite rock star. I create Alice to be--what would I want to see this

character do? And I talk about Alice in the third person because when I play

Alice, I play him in the third person. And so, would Alice say `thank you?'

No. Alice wouldn't get up there and go, `Gee, I hope you like us tonight.

And here's a song we wrote in 1968' and all this. Alice gets up there and

grabs them by the throat and says, `Come here. You're mine.' He's almost the

dominatrix.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. COOPER: You know, and the audience is his trick, as far as he's

concerned, you know? Now, at the end of the show, during the encore, when I

come back out, I take the makeup off. And that's when it's, `Hey, everybody,

this is the band, duh-duh-duh,' and I talk very freely to the audience. Why?

Because the makeup's not there, and it's not Alice anymore.

GROSS: Huh. What were some of your favorite horror films that helped inspire

Alice?

Mr. COOPER: Well, now, I was a kid, now, you have to remember, in the '50s.

So I--on Saturdays, Mom dropped us off at the theaters, and there were three

or four great horror movies: "It Came from Outer Space," "The Thing."

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: All those great '50s movies. And 30 cents and you were there

all day. And now, of course, they're camp, you know, and "Creature from the

Black Lagoon" and all that stuff. But I learned to really enjoy those kind of

movies. And I think, maybe collectively, that's where I started creating

Alice.

GROSS: Alice Cooper will be back in the second half of the show. I'm Terry

Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of "No More Mr. Nice Guy")

Mr. COOPER: (Singing) I used to be such a sweet, sweet thing

Till they got ahold of me

I opened doors for little old ladies,

I helped the blind to see

I got no friends 'cause they read the papers

They can't be seen with me

And I'm gettin' real shot down

And I'm feeling mean

No more Mr. Nice Guy

No more Mr. Clean

No more Mr. Nice Guy

They say he's sick, he's obsce-he-he-hene

(End of soundbite)

(Announcements)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross, back with Alice Cooper. He

became famous in the '70s for his intentionally decadent, taboo-breaking

theatrical rock concerts. Here's his 1975 recording "Welcome to My

Nightmare."

(Soundbite of "Welcome to My Nightmare")

Mr. COOPER: (Singing) Welcome to my breakdown,

I hope I didn't scare you

That's just the way we are

When we come down

We sweat and laugh and scream here

'Cause life is just a dream here

You know inside you feel

Right at home here

You're welcome to my nightmare, yeah

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Alice Cooper's shows usually end with him being executed onstage. I

asked what's his favorite way of being executed.

Mr. COOPER: Well, nothing's more effective than the guillotine, because the

guillotine, there's a certain amount of real anticipation behind it. You see

that blade.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: It's a 40-pound blade, it's razor sharp, and it really only

misses me by about six inches.

GROSS: It's a real guillotine?

Mr. COOPER: Oh, yeah. And it's a good trick. But if I didn't do the trick

right, it would cut my head off. I mean, it's--don't try this at home, by the

way. I'm a professional.

GROSS: Can you describe the trick, or would that be giving too much away?

Mr. COOPER: In case any of you people have guillotines at home.

GROSS: Well, it's a trick--it's an old vaudeville trick. In fact, you know,

when guys like Groucho Marx would come to the show--Groucho saw us as the

last--he always called me, he says, `You're the last hope for vaudeville.' And

he would bring Jack Benny and George Burns and Mae West. And people like that

would come to the show, because it was vaudeville to them. They said, `Ah,

remember 1923? The Great Floyd used to do that! You know, remember? Of

course, he would have doves come out of his sleeves when he'--and this was

nothing new to these guys. They would, you know, Groucho would come to the

show and he'd see it, and he'd go, `Ah, rawr rawr rawr.' You know, he'd insult

everybody there. `Excuse me, I got to go insult the maitre d'.' You know,

that kind of thing. We were best of friends, Grouch and I were. But they saw

it as vaudeville, and actually that's what it is. It's rock 'n' roll

vaudeville.

But this generation--the last five generations have no idea what vaudeville

is. So to them, it's something new. It's some kind of strange, dark cabaret.

GROSS: So can you describe the guillotine trick, like how it's done?

Mr. COOPER: Well, the guillotine, you actually--you are in the guillotine in

a stock, right? And you are holding yourself up with the hands. The audience

sees your head in the stock, and there's a basket in front of you. What they

don't see is that when the guillotine comes down, it's one point, you let

yourself go and your whole body drops, OK? They don't see that. They only

see your head lop off. Because they only see your head fall down, and then

there's a fake back that comes up and gives it the illusion that your head

literally came off. And if you see it on video, it is so effective that you

can stop it and start it, and that head comes off.

Now, we learned the trick--it was an old vaudeville trick. But it had been

perfected and perfected. The Great Randy was one of the guys that helped us

with it. And it looks perfect. In other words, I wouldn't do it unless it

really did look good. And then, of course, there's another head in the

basket. There's a perfect Alice head.

GROSS: Right. That they can parade around. Yeah.

Mr. COOPER: And they pull it out...

GROSS: Uh-huh.

Mr. COOPER: ...it's my head. And by that time, I'm already off the stage.

I'm already gone. I'm already changing into white top hat and tails.

GROSS: So, you know, at the end of a show, there's always a sense of relief

and release, you know, that the show is done.

Mr. COOPER: Yeah.

GROSS: Must be particularly so when you're getting executed at the end.

Mr. COOPER: Well, there's not much more you can do. I mean, your head just

came off. And I always say that, you know, if you're in the first 10 rows,

don't wear your best clothes. Because when that head comes off, we make sure

that everybody gets, you know, an artery goes. And, you know, it sprays blood

over everybody. You know, people are covered in stage blood. But they want

to be as close as they can get so they can walk out with the blood splattered

all over them and say, you know, `Alice got me with the blood tonight. It was

great.' You know?

And then, of course, the guy, the executioner, pulls the head out, and the

head is rigged so that he looks at the head, he talks to it, and he turns

around, and the head spews blood out of its mouth into the audience, like it

throws up what's left of it. It's not dead yet, you know? Now, it's so over

the top that if you're not laughing by now, there's something wrong with you.

Because it's...

GROSS: But the thing is, though, that some of your fans took it really

seriously, which leads to the chicken story.

Mr. COOPER: Well, in the beginning.

GROSS: It leads to the chicken story.

Mr. COOPER: Yeah, yeah.

GROSS: Tell the chicken story.

Mr. COOPER: Which, of course--well, no, the chicken story was one of those

things that--nobody saw that one coming. We're playing in Toronto, and my

manager, Shep Gordon, who I've been with 38 years, who's also total

vaudeville, totally gets it, you know? He's the one guy that always goes,

`Let's go for the Hollywood publicity stunt.' You know? We were going to go

on between John Lennon and The Doors. Now, you have to remember, nobody's

ever heard of us. But he promoted the concert, and 60,000 people there. And

we didn't get paid. Our payment was that we went on at the end, between the

two biggest acts.

So at the end of our show, we always used to do a thing where we would open up

a feather pillow and CO2 cartridges, and the whole stage was a flurry of

feathers. One or two pillows could fill Madison Square Garden, you know, with

a CO2 cartridge. In the middle of all this, all of a sudden, I look down and

there's a chicken. Somebody threw a chicken onstage. Now, it never occurred

to me, here's a guy, `Let me see, I got my keys, I got my tickets, I got my

drugs, I got my chicken, I got'--who would bring a chicken to a rock concert?

It wasn't us. We didn't bring it. I mean, I'd never have thought of using a

chicken onstage. So there's this white chicken, and, being from Detroit,

never being on a farm in my life--it had feathers, it had wings, it was a

bird, it should be able to fly. Is that not logical?

GROSS: I understand. I understand.

Mr. COOPER: Well, yeah. And I pick it up, and I kind of like softly, you

know, throw it into the audience, where it didn't fly as much as it plummeted

into the audience, and the audience tore it to pieces.

GROSS: Yeah, and...

Mr. COOPER: Next day in the paper, `Alice Cooper rips chicken apart and

drinks the blood,' and I was the new geek of all time. Of course, nobody had

a picture of it because it didn't happen. Now, I got a call the next day from

Frank Zappa, who was producing me at the time, and he goes, `Alice, did you

kill a chicken onstage last night?' And I went, `No.' He says, `Well, don't

tell anybody. They love it!' He says, `Everybody's talking about it!' He

says, `You're the new, you know.' So...

GROSS: I guess there's a part of me that wonders if, in a way, Alice wasn't

the villain here in the sense that maybe the fans were kind of behaving the

way they thought you wanted them to behave, or the way they were expected to

behave at an Alice Cooper concert, you know? `A chicken? Yeah! We're

villains, too! Let's get the chicken!'

Mr. COOPER: Yeah, that could be it. And it also could be the fact that they

were the ones that were high. We weren't. We were in the band.

GROSS: Mmm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: We didn't get high. We drank a little beer. That was about it,

you know?

GROSS: But did you ever think, like, `What am I bringing out in my fans?'

Mr. COOPER: Well, you know...

GROSS: `Am I making these people a little weird and crazy and violent?'

Mr. COOPER: When I thought of--yeah, not violent. Because here's the

strange thing, we never had violence in our audience. That was always the odd

thing. We had--my show was designed, to this day, that if you look away from

the stage, you're going to miss something. And that, I've always, shotgun

theater. You know, this song happens, boom, this is happening, Alice has got

a crutch up there, OK, the crutch is gone, now he's got a sword, the sword's

got money on it, now there's money flying in the air, did it--we don't give

them a chance to look away from the stage. So we never have fights in the

audience. We never have people getting in trouble. You take a boring act and

put them up there, and the audience will fight, but not during an Alice Cooper

concert.

GROSS: Well, here's one other thing I'm wondering about like the act, you

know, the theater. Like, there was one song in which you would have these,

like, dismembered parts of female mannequins...

Mr. COOPER: Yeah.

GROSS: ...and do really...

Mr. COOPER: Or just parts of any mannequins, yeah.

GROSS: You know, but really crude things with them, and I'm thinking of,

specifically here, the female mannequins.

Mr. COOPER: Yes.

GROSS: And, you know, of course, that makes me wonder like what message is

that sending, or what impact is that having on like the youngest male members

of your audience who think like, `Yeah, that's what sexual is.' Did...

Mr. COOPER: Yeah, yeah, and the weird thing about it was, at that

time--not--and I think I only did that once, and I think that was in the

"Billion Dollar Babies" show.

GROSS: Yeah. Uh-huh.

Mr. COOPER: And it never returned after that.

GROSS: Oh, OK.

Mr. COOPER: But it was--at the time, it was very dada. It was very Salvador

Dali-esque. There was no phallus. There was nothing--it was obviously

mannequin parts.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: And, you know, when people said, `Alice Cooper, oh, killed

babies onstage.' No. I killed dolls onstage, baby dolls. And Alice had this

thing where he'd throw billion-dollar babies--on "Billion Dollar Babies," I

would throw baby dolls in the audience. You know, little rubber baby dolls.

And I would have one on the end of my sword, and I would throw it out there.

The song "Dead Babies" was about parental abuse. It had nothing to do with

killing babies. I said, `Yeah, killing babies because parents aren't taking

care of their babies.' I had nothing against babies. But I did like throwing

dolls around. I thought there was something about that. Maybe that was

having a big sister or something like that. I was always afraid to bring a

psychiatrist to my show. I was afraid they'd read too much into it.

But it was always--the funny thing about it was, if Salvador Dali would've

done that, people would've gone, `Ooh, that's very artistic.' You know? But

Alice Cooper does it, and they go, `Oh, I don't know about that.'

GROSS: My guest is Alice Cooper. His new memoir is called "Alice Cooper:

Golf Monster." More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is Alice Cooper. He has a new memoir about music and golf.

It's called "Alice Cooper: Golf Monster."

You know what I find almost amusing? Like, the stage show is so much like

darker and more malevolent than a lot of the records themselves are. I mean,

like, and some of the records--and this is '70s we're talking about.

Mr. COOPER: Yeah.

GROSS: But, like, take "Desperado," which is, you know, has a lyric like, `I

wear lace and I wear black leather.'

Mr. COOPER: Yeah.

GROSS: And this is about, you know, `My hands are on my gun and'...

Mr. COOPER: You know what that song is written about?

GROSS: `My shots are clean, my shots are final.'

Mr. COOPER: Yeah.

GROSS: But the music is, like there's an instrumental break in the music

where there's symphonic violins playing, and it's so...

Mr. COOPER: Yeah.

GROSS: It's so, like, this symphonic music break in the middle of that song

is so...

Mr. COOPER: It's beautiful, right.

GROSS: ...different from anything that the Alice Cooper theater image would

present. It's...

Mr. COOPER: Now, that song in particular was...

GROSS: Yeah. Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: My favorite movie was "The Magnificent Seven."

GROSS: Oh, I love that film.

Mr. COOPER: OK, now, remember Robert Vaughn's character? He was the guy

with the black--he had the black vest on, he had the two chrome guns, he was

the fastest gun. He was the gambler. He had the white lace shirts, and that

song was written about him.

GROSS: Oh.

Mr. COOPER: "I wear lace, and I wear black leather. My hands are lightning

on my six guns. My shots are clean, my shots are final." You know, it was

about him. And, of course, I always loved the idea that the audience was

allowed to make up their own interpretations. I always said, the best thing

we can do here is don't write a story, bombard the audience with images and

then take 10 people and ask them what happened in that show, and they'll tell

you 10 different things.

GROSS: My guest is Alice Cooper. Let's hear the track we've been talking

about, "Desperado."

(Soundbite of "Desperado")

Mr. COOPER: (Singing) I wear lace, and I wear black leather

My hands are lightning on my guns

My shots are clean, and my shots are final

My shots are deadly, and when it's done,

You're as stiff as my smoking barrel,

You're as dead as the desert night

You're a notch and I'm a legend,

You're at peace and I must hide

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's "Desperado" by my guest, Alice Cooper.

So how did you end up having, you know, like, you know, string instruments,

like orchestral instrumental breaks on Alice Cooper records?

Mr. COOPER: Bob Ezrin. Bob Ezrin was our George Martin. Now, when--we were

a pretty raw rock 'n' roll band.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: A very inventive rock 'n' roll band, you know, we learned from

The Yardbirds and The Who, and we really were a very good rock band with a lot

of good little hook-y ideas. Now, Bob Ezrin came along. He was our producer

from Toronto, worked with Jack Richardson. And he saw it and said, `I'm going

to take and shape this into something that is purely Alice Cooper. It has

Alice Cooper signature all over it.' We quit touring for six, seven, eight

months, maybe, and did nothing but relearned how to play our instruments,

relearned how to sing, relearned how to write. And that's when "Love It to

Death" came out with "Ballad of Dwight Fry" and "Desperado" and those songs

and everything like that. And it was a new Alice. But it was an Alice that

was really melodic.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: And Bob Ezrin would say--he would do this. We would, of course,

hear a song and we would add guitars and add this and add this. Bob would

subtract things. He would say, `Let's take all of this out and just have that

one piano going there. This one lonely little piano, and then this whole wave

of strings will come in.' He says, `And they're not expecting that.' And when

those strings are just like singing above everything with your voice here in

the middle, then the guitar comes in. But one guitar, not six guitars.

And pretty soon--we would argue with him and say, `You're taking all the best

parts out, duh-duh-duh-duh.' Then we'd listen to it and go, `Oh, man, that's

great.' You know, Bob really--we gave him full reign. We would write the

songs, record it, and then we would let him add the oboe here that like

doubled the bass. And he would add a piano that doubled that guitar. And

this and this and this. And it was magnificent, what he was doing.

GROSS: Yeah, well, even "Welcome to My Nightmare" has horns in it.

Mr. COOPER: Oh, it's got all kinds...

GROSS: Symphonic sounding horns.

Mr. COOPER: "Elected" sounds like Leonard Bernstein piece, you know? But

that's all Bob Ezrin.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Alice Cooper, and he has a new

book that's part memoir about his life and his band, and it's also part about

golf. And it's called "Golf Monster." And he describes himself as a golf

addict.

Mr. COOPER: Yes.

GROSS: Now, we talked a little bit about how when you were growing up, you

know, your father was a pastor. Your grandfather had been the head of the

Church of Jesus Christ.

Mr. COOPER: Yes. Not LDS, it was a Protestant church.

GROSS: Mm-hmm. Not a Mormon church.

Mr. COOPER: It just happened to be called--no, not at all. No.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: It was called the Church of Jesus Christ, but there was LDS

after it.

GROSS: Right. So with people--with father and grandfather who were so active

in their churches and who were, you know, missionaries, too..

Mr. COOPER: Yes.

GROSS: ...when you started doing Alice Cooper, was there ever a little voice

in your head saying, `I am behaving sinfully'?

Mr. COOPER: I was the prodigal son. I couldn't get further away from the

church. I became the poster boy for sin. I was, you know, pretty much, you

couldn't get much worse than Alice Cooper. Of course, I was getting richer

and bigger, and we were voted number one band in the world at one point.

Combined with hit records, you couldn't--that was what kept me going, was the

fact that there were hit records, and people couldn't deny that. Sold out

shows everywhere.

Now, when I got out there and I became an alcoholic and--there was that voice

that said, `What are you doing out here?' Because I did believe in Jesus

Christ; I did believe in God. In fact, a lot of my songs in the early

days--there's a song called "Second Coming"--a lot of my songs had lots of

biblical reflections and things going on. Now, about 1980, I checked into a

hospital because I was throwing up blood in the morning.

GROSS: Mm.

Mr. COOPER: And I came out of the hospital, and I was the classic alcoholic.

I couldn't walk from A to B without a drink in my hand. I came out of the

hospital, and never once had a craving for alcohol. Not one craving. I

didn't go to AA, didn't have a therapist, didn't have a psychiatrist, I had no

backup. I just went, `It's gone. It's absolutely gone.' So people said,

`Well, you had a very good cure.' I said, `No, I was healed.' Because there...

GROSS: Is that when you became a Christian again?

Mr. COOPER: Well, when I saw the evidence of the fact that God did something

extraordinary with me. He--not because I deserved it, but it was as though

one day they took a X-ray and I had cancer, let's say, and they took the X-ray

the next day and the cancer was totally gone, and they went, `Where did it

go?' It just disappeared. I was an alcoholic of the highest order one day.

When I came out, I was not. Twenty-six years, I've never had a drink. And I

don't--it would never occur to me to have a drink.

GROSS: My guest is Alice Cooper. His new memoir is called "Alice Cooper:

Golf Monster." More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is Alice Cooper. He has a new memoir about music and golf.

It's called "Alice Cooper: Golf Monster."

Can I just name a few names to you and get your really short take on them?

Mr. COOPER: Sure.

GROSS: Great. Kiss.

Mr. COOPER: Kiss. We told Kiss where to buy their makeup. Everybody wanted

there to be a huge feud between Kiss and us because they were the great

copycats. Alice came out with the makeup, Kiss came out with the makeup.

Their very first statement was, `If one Alice works, then four ought to work.'

Now, my joke with them--and they're friends of mine--was they use pyro. I

never used pyro. I said, `As long as you guys do something, don't do my show,

and do different records, there's room for us both out here. Just don't be

Alice Cooper.' So they turned into four comic book characters.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: They were like the X-Men...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: ...whereas Alice Cooper was "Phantom of the Opera," you know? I

always used to laugh and I'd say, `When you guys can't think of anything

clever to do, you just blow something up.'

GROSS: OK. "Rocky Horror Picture Show."

Mr. COOPER: Based on Alice Cooper.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. COOPER: Absolutely. I saw the director's notes. Every time they

mention Frankenfurter, they said, `a la Alice Cooper.'

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: Now, see, that show had a great sense of humor. You know, I

mean, we watched that--and I don't care if you were Christian or

non-Christian, you watched the show and you were laughing your head off

because it was so ridiculous. But it's so over-the-top vaudeville that, I

mean, you have to laugh at it. I object to some of the humor, I object to

some of the, you know, things, but so what? You know? Everybody's going to

object to something.

GROSS: Marilyn Manson.

Mr. COOPER: Marilyn Manson, you know, understood what Alice was, looked at

it and said, `I'm just going to up the ante. I'm going to be Marilyn Manson.'

OK, Alice Cooper, Marilyn Manson. OK. Let me see, a girl's name. Gee, I

wish I would've thought of that. Makeup? Oh, wait a minute. I did that.

But he said, `OK, my thing is, now, Alice did makeup, snakes and

violence--mock violence onstage. OK, what am I going to do? OK, I'm going to

be a devil worshipper, drug addict, duh-duh-duh. That'll get them.' What he

does is very stylistic.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: I think he's missing the sense of humor in it, and I certainly

object to a lot of the things when it comes to tearing pages out of the Bible,

and he became an anti-Alice as soon as he heard I was Christian.

GROSS: Really?

Mr. COOPER: He just publicly said, `Alice is--I hate Alice now.' `Why?'

`Because he's Christian.'

GROSS: Hm.

And I want to ask you about Frank Sinatra, and here's why: in a concert film

from 1973, you come out first in a white tuxedo singing "The Lady Is a Tramp,"

a song Sinatra made famous.

Mr. COOPER: (Singing) She gets too hungry for dinner at 8...

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. COOPER: Yeah. Well, he was the first punk.

GROSS: Wait, wait, wait. Then you say, in the middle of the song, you go,

`I've had enough of this,' and you act like really angry, and you strip out of

the...

Mr. COOPER: Right.

GROSS: ...out of the tuxedo and start getting into Alice Cooper drag, but I

figured you must love Sinatra.

Mr. COOPER: Loved Sinatra. He actually was a friend. And Frank Sinatra

totally got Alice Cooper. In fact, all of the Hollywood guys, the old pros,

got Alice Cooper. They got it. They understood what it was. They saw the

image. They said, `Oh, I get it. OK, cool, he's playing this thing to the

hilt. Way to go.' And the hit records keep coming. Frank Sinatra did one of

my songs. He did "You and Me" at the Hollywood Bowl one night. I actually

got along quite well with Frank Sinatra. He looked at me as an original, and

of course, everybody--you can't beat Sinatra. He's the best voice of all

time.

GROSS: Just one more thing. It sounds like your voice is in pretty good

shape, which is kind of amazing considering how many years you've been singing

real loud onstage.

Mr. COOPER: I never smoked.

GROSS: Is that it?

Mr. COOPER: Yeah. Never smoked. Yeah.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COOPER: I never--wasn't a smoker, and I quit drinking 26 years ago. And

a lot of the guys I know, I mean, the Steven Tylers and the Iggys and people

like that that were heavy smokers, yeah, do have some problem with lungs, I

mean, in as far as lung power. Now, you have to remember, on top of that I

was a distance runner.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. COOPER: I mean, so I can get up and do five shows a week, two hours a

night, at a much more breakneck pace than these guys do, and it's because

that, I think, that I never had a lung problem. I didn't have problems with

that.

GROSS: Well, Alice Cooper, it's really been fun talking with you.

Mr. COOPER: Thank you very much. We've done some fun stuff.

GROSS: Alice Cooper concluding our hard rock, heavy metal series. Our

interview was recorded last spring after the publication of his memoir, "Golf

Monster."

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.