Other segments from the episode on August 11, 2008

Transcript

DATE August 11, 2008 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

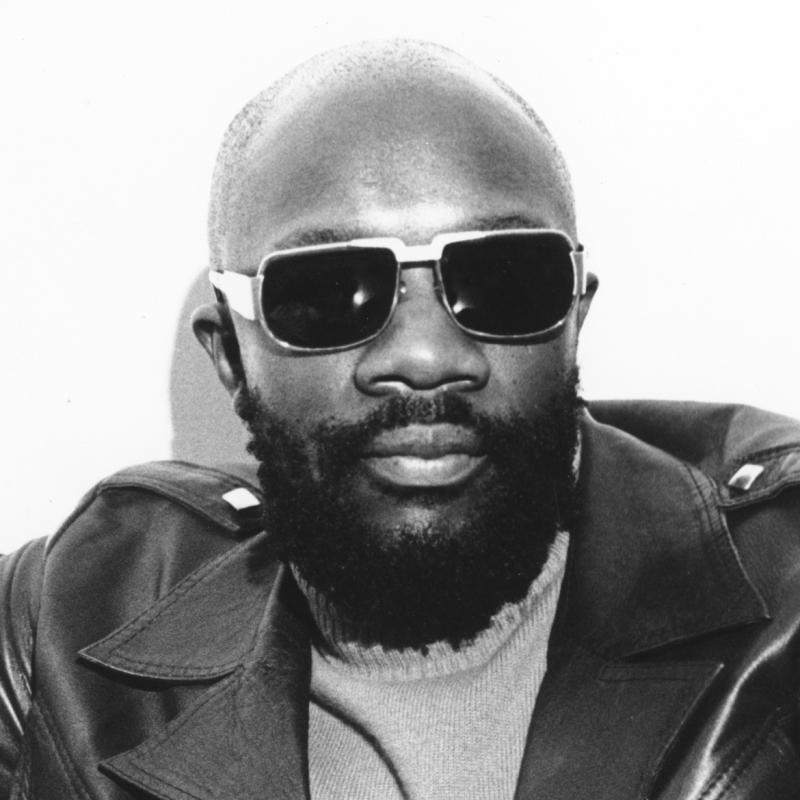

Interview: Isaac Hayes discusses his music and acting career

DAVE DAVIES, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies, senior writer for the Philadelphia Daily

News, sitting in for Terry Gross.

Isaac Hayes, the singer, songwriter, composer and producer whose soul sound

changed the world of music, died yesterday at his home in East Memphis,

Tennessee. He was 65.

Hayes is perhaps best known for his bass baritone voice and the theme to

"Shaft," which won an Academy Award in 1972. Born in rural Tennessee in 1942,

Hayes began playing with local bands and became a songwriter, producer and

arranger for Stax Records, the legendary Memphis R&B label. He recorded

several hits there, including the album "Hot Buttered Soul" and the

Grammy-winning "Black Moses," which influenced later generations of disco and

hip-hop artists. Hayes also developed a trademark look with his shaved head,

gold chains and bare chest. In the '80s and '90s, Hayes found an acting

career, with roles in the "Rockford Files" and the films "Escape from New

York," "The Duke," and the loving parody of blacksploitation films "I'm Gonna

Git You Sucka." And he gave his voice to the character Chef on the animated

series "South Park" until 2006. He continued performing in recent years

despite health problems. Terry spoke to Isaac Hayes in 1994.

TERRY GROSS, host:

Now I know before you started making your own records, before you started

singing in your records, you produced for other people, and also you played

piano and keyboards. And you used to play with Booker T. & the MGs. Now how

did you learn to play piano, growing up as poor as you did? I know there were

times in your life when you didn't have shoes, let alone a piano.

Mr. ISAAC HAYES: That's true. How did I do that? Well, let's see. A

friend of mine I grew up with, Sidney Kirk, used to be my accompanist. We

went places and he'd play for me. He joined the Air Force; he wasn't there.

There was a call in to him about a gig New Year's Eve. His sister knew that I

was destitute and I needed money, so she asked me if I wanted to play? Well,

I could play maybe "Chopsticks" and stuff like that. And I said, `Yeah, I'll

take it.' I took the gig out of desperation. And when I got to the club, I

was petrified. I said, `Oh, my God, they're going to shoot me. I can't

play.' And musicians started coming in, you know, setting up, tuning up, and

I'm sitting there, you know, trying to be cool. I said, `God, they're going

to find me out.' And the featured artist came in and said, `Hey, man, do you

all know such-and-such?' This is the first time this band had been put

together. We didn't rehearse anything.

And everybody said, `Yeah, we know it, and blah, blah, blah.' So he kicked off

the tune, and it sounded horrible. Everybody did. I said, `Wow, these guys

can't play either.' So I'm comfortable. And, you know, being New Year's Eve,

the clientele was drunk, and they thought we were cooking, you know? And

somewhere along the line, the club owner--he was sauced--he came up and said,

`You know, you boys sound real good. You all want a regular job?' `Yeah,

we'll take it.' And that was in Memphis and it was a regular gig, and each

night I would learn something more and more on the keyboards. And that's how

I got started.

GROSS: That's great. And then you started sitting in with Booker T. & the

MGs.

Mr. HAYES: Well, I wound up at Stax Records. I changed bands and I joined

Floyd Newman's band, who was a staff musician at Stax. He played baritone

saxophone. All those ba-dups, stuff like that, that was Floyd. So he was up

for a recording. He said, `Man, you know, we're going in the studio.' And

prior I had been to Stax about three different times with a blues band, with a

vocal group, you know, trying to get a break, and was always turned down.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HAYES: This time I went in with Floyd and Howard Grimes, a drummer, he

and I wrote some songs, some instrumentals and things like that. And Jim

Stewart, who, you know, was co-owner of Stax, he said, `You know, you sound

pretty good on keyboards. Booker T. is off at Indiana U. in school. Would

you like to become a staff musician here?' `Yeah!' You know? So that's how I

got in Stax.

And my first session, I think it was an Otis Redding album session, I was

scared to death, but he made it easy. And I learned a lot and I fit right in.

And I became a staff musician. So when Booker came back, he and I both played

on sessions. We'd switch around. Sometimes I'd play organ and he'd play

piano, and sometimes I'd play piano, he'd play organ. And with "Duck," Steve

and Al, we were the nucleus of Stax, the rhythm section, and then, of course,

the horns and so forth.

GROSS: Now you were not only a house musician at Stax, you became a house

songwriter. And you wrote a lot of songs with your partner then, David

Porter. And some of the most famous songs that you wrote were for Sam and

Dave, like "Soul Man" and "Hold On, I'm Coming." What do you remember about

writing "Soul Man"?

Mr. HAYES: Well, I remember getting the idea from watching TV and the riots

in Detroit, and it was said that if you put soul on your door, your business

establishment--they would bypass it and wouldn't burn it. And then the word

"soul"--you know, the clenched fist, you know, "soul brothers," soul this--it

was a galvanizing kind of thing as far as, you know, African-Americans were

concerned. And it had a kind of effective unity, and they said it with a lot

of pride. So I said, `Well, hm, why not write a tune called "Soul Man"?' And

all you had to do was write about your own personal experiences because, you

know we, everybody, all African-Americans in this country, during those times

especially, had similar experiences. So we did that. But realized that, in

addition to being an African-American experience, it was a human experience;

so therefore it crossed the board. And then the groove and everything else

that went with it just made it, you know, very, very commercial.

GROSS: So did you arrange this too?

Mr. HAYES: Yes. Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And are you featured instrumentally?

Mr. HAYES: I wasn't featured. I just played piano on it. Well, you know, I

did some little hot licks in there and stuff like that.

GROSS: OK. Well let's hear "Soul Man," co-written by my guest Isaac Hayes.

(Soundbite of "Soul Man")

SAM and DAVE: (Singing) Coming to you on a dusty road.

Good lovin', I got a truckload.

And when you get it--Ha!--you got some.

So don't worry 'cause I'm coming.

I'm a soul man. Yeow! I'm a soul man.

I'm a soul man. Whoa! Hey! I'm a soul man,

and that ain't all.

Got what I got the hard way,

and I'll make it better, each and every day.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: So how come it took several years for you to actually record your own

vocals?

Mr. HAYES: Well, I started singing in high school. I sang before ninth

grade, preteen, I used to sing. But I sounded like somebody in the Vienna

Boys' Choir.

(Singing) My voice was way up there like that.

And they would call me, `Oh, man, you're a sissy.' So when I reached puberty,

my voice started cracking and squeaking, and then when it cleared up, it was

down in the basement. So I started singing again, and I was singing jazz

during my teenage years. I was singing jazz in a little nightclub, I was

singing with blues band, I was singing with a rock 'n' roll group called the

Teen Tones, I was singing with a gospel group called the Morning Stars. We

had a little combo, and during my senior year we played. So I had all this

experience, and I would to go Jim Stewart and say, `Hey, Jim, I want to

record. I want to try some.' `Well, Ike, you know, we have an R&B label and

your voice is too good. It's too good for what we're doing here.'

So I never did get the shot until one day it was someone's birthday party at

Stax, and we always serve champagne and cake. And we had gobbled down some

cake, and Duck Dunn and I grabbed a couple of bottles of champagne and ran

into the ladies restroom and closed the door. And we just guzzled this

champagne down. I mean, I got a buzz. Came out, Al Bell, who at that time

was the head of national promotion--he wound up being executive vice

president--but he said, `Ike, I want to cut something on you.' `OK, yeah. I

don't care.' I was feeling no pain. So we were going into the studio, Al,

Jack's on drums, Duck on bass and myself on piano. And I said, `Man, you all

follow me.' It was all impromptu. And we stayed in the studio a few hours.

And we finished. Al said, `OK, I got what I want.' And that wound up being

"Presenting Isaac Hayes," my very first album.

GROSS: You developed a style of singing in which you did long raps. It kind

of gave a back story to the song. And the rap would lead you into the song.

And the songs are often, you know, like pop tunes other people had written,

like "By the Time I Get to Phoenix."

Mr. HAYES: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: But you'd kind of make up the whole story leading up to it. How did

you start doing that, combining these raps with pop tunes?

Mr. HAYES: Remember the famous quote in "Cool Hand Luke"? I forget the

actor's name. "What we have here is a failure to communicate."

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. HAYES: Remember that?

GROSS: Sure.

Mr. HAYES: Well, I did that. The rap came out of the necessity to

communicate. And the way it happened was, there's a local club in Memphis

predominantly black that was called the Tiki Club. And, you know, we'd hang

out there, the Bar-Kays were playing there sometimes, and we'd hang out there

and sit in. You know how musicians do. And this one day, I heard this song

by Glen Campbell, "By the Time I Get to Phoenix." I said, `Wow, oh, that

song's great. I mean, this man must really have loved this woman.'

And so I ran down to the studio later on that day and said, `Man, you all hear

this song "Phoenix"? Man, it's great.' Everybody, `Yeah, yeah.' You know, no

enthusiasm. I was saying, `These guys don't feel what I feel. What, are they

getting it?' So the Bar-Kays were scheduled to play the Tiki Club a couple of

days later, and I said, `Hey, man, I'm coming down to sit in with you guys.

Learn "By the Time I Get to Phoenix."' They said, `OK.' I told them the key,

in E flat.

And so I went down and the club was packed. Go up on stage, `Ladies and

gentlemen, you know, you all know him, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. Isaac

Hayes.' And, I mean, it's all kind of conversations going, you know, `Blah,

blah, blah, blah, blah.' I said, `Oh, man, how am I going to get these

people's attention?' So I said, `Hey, man, the first chord in the song, you

all hang up on it. It's a B flat 11. Just hang up on the chord. Just keep

cycling it.' And I started talking. And I just started telling this story.

It was a scenario about what could have happened to cause this man to leave,

you know. And I started talking and, halfway through the rap, the

conversations started to subside. And when I reached the first line in the

song, when I said, "By the time I get to Phoenix," everybody went `Oh, wow.'

And, you know, when I finished the song, there wasn't a dry eye in the house.

GROSS: Well, I want to play an excerpt of your recording of "By the Time I

Get to Phoenix." This is Isaac Hayes.

(Soundbite of "By the Time I Get to Phoenix")

Mr. HAYES: (Speaking) But one day, one day, old boy got sick and he had to

come home. I don't have to tell you what he found. Only it hurt him so bad.

He said, `Baby, mama, why?' That's all he could say. But she said, `Oh, go

on, fool. You're doing it.' But the man wasn't doing it. But that's the only

excuse she could give him. He said, `Mama, I can't take it. I got to leave

you. I'm going to leave you.' Well, she tried to straighten up. She said she

was going to straighten up. She got a little job to help him out with the

bills, too. But that was just a sham. Because he found it again. And again.

And seven times he left this woman, and seven times he came back. And he'd

taken all that he could stand. And the eighth time that this went down, he

said, `Mama, I got to go.' He said, `I'm leaving my heart right here.'

(Singing) Ooh, I don't want to go,

but I got to leave you, mama.

He said, `By the time I get to Phoenix, she'll be rising.

Oh, and she'll find a note I left hanging on the door.

She'll laugh when she reads the part that says I'm leaving.

Yes, she will.

Why? 'Cause I've left that girl so many times before.

Oh. By the time I make Albuquerque, she'll be working.'

(End of soundbite)

DAVIES: Isaac Hayes. We'll hear more of his 1994 interview with Terry in a

moment. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

DAVIES: Today we're remembering Isaac Hayes, who died yesterday, by listening

to his 1994 interview on FRESH AIR.

GROSS: Now you recorded the theme for the movie "Shaft" in, I guess, it was

1971. How were you asked to do this?

Mr. HAYES: Well, it was a whole concept. Hollywood recognized that they had

to look further than they had been looking to get business. I think it was

fledgling at the time. It was a bit stagnant. And Melvin Van Peebles had put

out a movie called "Sweetback's Baadasssss Song." And they said, `Hm. There

might be a market there. If we come up with a concept to have a black leading

man, black director, maybe a black composer, we might hit that market.' MGM

was the one that pioneered the idea. So we had a meeting out there at MGM

with Stax execs, and they asked me to come. And they talked about the

concept. And would I do the music? Would I be interested in doing the music?

Yeah. I said, `I want to act, too. Have you all cast for the lead role?'

`Well, no. We'll look into that.' But anyway, I think that was a stick and

carrot, you know? So.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. HAYES: So I agreed to do the music. They had already cast Richard

Roundtree, which was rightfully so, he's perfect for the part. And I agreed

to do the music. And that's how that whole idea came about.

GROSS: Here's where you really get into orchestrating, right?

Mr. HAYES: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: So tell me how you started using that wah-wah guitar funk style.

Mr. HAYES: Ha, ha. Well, OK. Trade secrets. What happened was, I had been

doing the arranging all the time. I did a lot of arranging with the horns and

stuff at Stax, and the first string arrangements I tried was a thing that

David and I did on Sam and Dave; and that album was like a big flop, but we

tried it anyway. But I had a taste for it. And once I had a taste for the

strings, I couldn't let it go. Now sometimes, in the studio, you're working

on various grooves and stuff and you can't find a name for it or you can't tag

it with anything. You just, if it feels good, you say, `OK, I'm going to file

that.' And you put it up. You put it back and you store it.

Now when it was time for me to do the "Shaft" theme, I said, `What can I do?'

You know, they explained the character to me, you know, `A relentless

character, always on the move, always on the prowl. And you got to get

something to denote that for the main theme.' I said, `What can I do?' I

thought about--if you remember Otis Redding's "Try a Little Tenderness," I had

a hand in that arrangement, too. In the end, Al Jackson was doing some stuff

on high-hat similar, you know. "You got to na, na, na, chicka, chicka,

chicka, chicka, boom." You know? So I thought about that. I said, `Maybe if

I just sustain that particular thing on the high-hat, that will give you a

dramatic effect and it's something that's relentless. Now what else can I

do?' I thought the guitar lick. And I went and pulled it out, played it; and

Charles Pitts, we called him "Skip," he played the thing on the wah-wah. I

said, `Hey, play this line.' And he started it. And I told Willie the

drummer, I said, `Willie Hall,' I said, `Give me that high-hat man, some 16

notes.' You know, chicha, chicha, chicha, chicha, you know. And he did that.

And it worked. I said, `That's the kind of dramatic effect I want.'

(Soundbite of instrumental introduction of "Shaft")

Mr. HAYES: Then I started putting the other things in, you know, the base,

the accents and all that stuff, but that's how that whole wah-wah thing came

about.

GROSS: Well, why don't I play some of your theme from "Shaft," a classic.

This is Isaac Hayes.

(Soundbite of "Shaft")

Mr. HAYES: Who's the black private dick that's a sex machine to all the

chicks?

Unidentified Backup Singers: (Singing) Shaft!

Mr. HAYES: You damn right!

(Singing) Who is the man that would risk his neck

for his brother man?

Backup Singers: (Singing) Shaft!

Mr. HAYES: Can you dig it?

(Singing) Who's the cat that won't cop out

When there's danger all about?

Backup Singers: Shaft!

Mr. HAYES: Right on.

(Singing) They say this cat Shaft is a bad mother

Backup Singers: Shut your mouth!

Mr. HAYES: I'm talking about Shaft.

Backup Singers: Then we can dig it!

Mr. HAYES: (Singing) He's a complicated man,

but no one understands him but his woman.

Backup Singers: John Shaft!

(End of soundbite)

DAVIES: Isaac Hayes spoke with Terry Gross in 1994. We'll hear more of their

conversation in the second half of the show. Hayes died yesterday at the age

of 65. I'm Dave Davies, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies, filling in for Terry Gross.

Today we're remembering singer, songwriter and composer Isaac Hayes, who died

in East Memphis yesterday at the age of 65. Terry spoke to Isaac Hayes in

1994.

GROSS: At the time that "Shaft" and "Super Fly" were really popular, I mean,

everybody now, all the black filmmakers now just credit those films with

paving the way to all the new work that's happening now. But at the time the

NAACP was appalled at the black action films. And I wonder what your reaction

was then to their reaction?

Mr. HAYES: Well, you know, I had mixed emotions about that. That position

was that, you know, it was painting a bad image...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HAYES: ...you know, for the kids and so forth, and there were no

alternatives. Had there been some alternatives at that time, then I don't

think the NAACP would have come down so hard. But what happened was when they

did that it was like it turned off the tap. It totally dried up for us

because I was a, `Whoops, hands off.' And they dropped everything. And our

whole little thing just died. I think, you know, in hindsight, had there been

a little more patience at the time maybe it could have taken off in some other

directions because that was--it was in its embryonic stage at that time, you

know, the black cinema.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HAYES: And anything in its infancy you going to get some--you'll get a

lot of crap. You're going to get some inferior things and all of that and

quality and so forth, and even questionable subject matters. But as that

particular genre grows then, you know, you start getting better films and so

forth. And I think they might have made a move a little bit too soon; because

when we were doing these things, we weren't taking ourselves seriously, not as

the characters. We were just glad to get the work, glad to get the

experience, glad that our people could see us on screen.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HAYES: You know, I mean, and...

GROSS: And as leading men.

Mr. HAYES: Yeah. You know, and not with a broom and a mop and bowing and

saying, `Yes, sir, boss.'

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HAYES: So, you know, so that's why, you know, it took off and was so

widely received. And I think had it had a little time to go, a little longer,

you know, you spin off in some other areas and Hollywood would have recognized

that there is more that could sell than, you know, the pimps and the hookers

and, you know, the private eyes and so forth.

GROSS: I want to spend a couple of minutes talking with you about how you

developed your image. When did you start shaving your head?

Mr. HAYES: I started shaving my head not long after I got out of high

school.

GROSS: It wasn't fashionable then, at least not to my knowledge.

Mr. HAYES: No, it wasn't.

GROSS: What inspired you to do it?

Mr. HAYES: Well, you know, during those times, as musicians, we--it was a

fad. We had a relax in our hair, called it a "do," a cork process. And

during that time mine was cut very low and just slicked down on my head all

the way around like a coconut, you know. And it was hip. It was the style.

But in the summertime, it was hard to keep up; and you sweat, and it come

undone and you had to sleep with a stocking cap on on the couch. I go, `I'm

sick of fooling with this stuff. I'm going to cut it off.' So I went to the

barber shop around the corner from Stax. I said, `Mr. King, cut it all off.'

`What?' `Cut it all off. I'm going to grow a new crop.' And when he cut it

off, you know, I went outside, you know, and I said, `Wow, it's a breeze out

here. It feels great. I can feel the wind on my head. Hey, I think I'll

keep it like this.' I already had the beard. And people would look at me and

say, `Oh, wow. Oh, look at this guy. Man, he's got a bald head and a beard.'

But I didn't care because it was different and I like being different, you

know, I like swimming up stream.

And a funny thing. One time Booker T., by some error, somebody booked two

dates on the same day for Booker T. and MGs. And one date was in--I think

Booker had to go to Oklahoma somewhere, and I went to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

with Al, Duck and Steve, and David Porter was a vocalist, and I was to pretend

to be Booker T. And I'm at the organ, we kicked off the tune, kicked off

"Green Onions," you know, and grooving. Somebody said, `Hey, man, that ain't

no Booker T. He ain't got no hair.' And I mean they were ready to riot. I

jumped up from the organ and got out there with David and started dancing and

singing and doing any other things trying to appease the people, you know.

But finally they said, `Well, OK, what the hell. We'll accept him.' And, I

mean, I played the entire gig. And, of course, years later I went back as

Isaac Hayes and I played Harrisburg and I told that incident and some people

remembered it and they cracked up.

GROSS: That's funny.

Mr. HAYES: But I mean I was an unknown, but I just looked different. I

liked the different look.

GROSS: Are you still doing it?

Mr. HAYES: Oh, yeah. You see the thing about it is it's ageless. So when I

go naturally no one will know.

GROSS: Now, how did you start wearing gold and velvet and furs?

Mr. HAYES: Well, you mean just day to day or...

GROSS: Well, I don't know what you wore day to day, but I know you certainly

wore that on stage.

Mr. HAYES: Oh. On stage I wore, OK, French rabbit boots. I wore tights of

different color. And I wore chains. Now--and I come out with a cape and a

floppy hat. Why did I do that? OK, a sense for the dramatics. OK? You see,

at first I would wear, during the days of the hippies, I would wear a lot of

rawhide with fringes and beads and stuff and moccasins and bell bottoms. And

it was hot. It was hot. And later on I thought, I said, `When I see

entertainers perform, they come out with three piece suits on, with ties, and

the first thing they do is loosen the tie and throw the jacket off, and then

they might take the vest off.' I said, `Well, I'm going to go out there

already comfortable. So what can I do?' So I started wearing the vest and the

tights. Tights are comfortable. Ballet dancers wear tights, so why can't I?

And a guy gave me a chain necklace and a belt, and I tried that on stage. And

when I came out like that, women were screaming. You know, I was always

taking mental notes of effects and so forth. And I said, `Hmm, maybe I'll do

this.' And I started doing it and somebody suggested, `Why don't you put a

robe on because you want to go out there and give it to them all at one time.

Put a cape on and then throw it off when you get out there.' I tried that

effect. Wow. Then I put a floppy hat on and showed my head later, because I

remember one time I went out on stage and I had a hat on and I started

sweating. I took it off to wipe my head and women screamed. `Hmm. OK, I'll

use that too.' And then this guy named Charles Rubin said, `Isaac, I have an

idea. I'm going to make you some chain vests.' I said, `OK, try it out and

we'll see.' And he made them and it worked, and that's how that came. But I

just like--I was a renegade. I had a renegade mentality. I always liked to

be different.

GROSS: Did you dress like that in private?

Mr. HAYES: No. No. I mean, I dressed, I mean, I dressed real fly. If you

remember in Guralnick's book, he described I had a purple suit on with some

purple shoes and--whatever it was--standing outside of Stax. Remember? So I

always dressed flamboyantly. I mean, you know, always flashy. I would dare

to wear things nobody else would try to wear. I, you know, I had a girl that

made me some Nehru suits and stuff like that back when nobody would wear them.

I saw the "Pink Panther" and I liked the way that--remember the first one

where Capucine, her chaperone, this guy was always around--tall, slim guy--had

these Nehru collars and stuff on, and I liked that look. So I had a girl to

make a lot of those things for me.

GROSS: So this must have been real different from when you were growing up

and you virtually had no clothes, you had no shoes.

Mr. HAYES: Hey, you could put me out in the corn field and I'd scare the

crows away, you know. You know, when you're like that, when you grow up in

poverty and you think about that meal you're going to have, you'll never be

hungry again, Scarlett O'Hara. You think about the clothes you're going to

wear. You think about the house you want to live in. You think about the

cars, you know. So when you start acquiring affluence, money, you buy these

things and you enjoy it. And I worked all of my child--I didn't have a normal

childhood, you know, like growing up, because I had to become the man of the

family at an early age; so I didn't have a lot of chance to do the play things

that kids do. So when you grow up and have the money, these things become

toys and it becomes fun to you.

GROSS: I thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. HAYES: Well, Terry, it's been my pleasure.

DAVIES: Isaac Hayes speaking with Terry Gross in 1994. Hayes died yesterday

in East Memphis, Tennessee. He was 65.

Coming up, we remember comedian Bernie Mac who died Saturday.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Bernie Mac discusses his career as a comedian

DAVE DAVIES, host:

Comedian Bernie Mac died Saturday at the age of 50 due to complications from

pneumonia. With his five year run on the Fox series "The Bernie Mac Show," he

was one of the few African-Americans to play a leading role in a network

program. In 2002, "The Bernie Mac Show" won an Emmy for Outstanding Writing

and a Peabody Award. The real Bernie Mac became well known through the

Russell Simmons Def Comedy Jam on HBO, and Spike Lee's performance film "The

Original Kings of Comedy." Bernie Mac also starred in "Oceans 11", 12," and

"13," as well as "Bad Santa" and "Get on the Bus."

Terry spoke with Bernie Mac in 2001 when "The Bernie Mac Show" was just

premiering. The sitcom was loosely based on Mac's experiences raising his

daughter, his niece and his niece's child. On the show, Bernie Mac and his

wife take in his sister's three young children because his sister has a drug

problem and is in rehab. In the first episode of the show, Bernie Mac talks

directly to the audience about his new situation.

(Soundbite of "The Bernie Mac Show")

Mr. BERNIE MAC: America, let's talk. Yeah, my sister's on drugs. That's

OK. Some of your family members messed up, too. What am I supposed to do?

Allow these three kids to go to the state or some foster home or some white

couple. Hold on, this ain't about race. It's not about race. I just don't

want to hear them talking all proper like that, you know what I'm saying?

That's all I'm trying to say. Or they got to sit there and share food with 40

other kids. No, that ain't right. I'm trying to do the right thing.

(End of soundbite)

DAVIES: Mac loves the kids he's now responsible for, but they also drive him

crazy.

(Soundbite of "The Bernie Mac Show")

Mr. MAC: I'm going to kill one of them kids. Oh, don't get me wrong, I love

'em. They my blood. I'd give them the shirt off my back. You ever see a

chicken with his neck wrung, laying to the side all lazy and weak? That's

what I'm going to do to them kids. Talk back to me one more time, snap. I'm

gonna snap they neck off. They too sassy. They too grown today. They talk

back too much. Yeah, I know what you're saying, America. I don't care what

you're talking about. `Bernie Mac cruel. Bernie Mac beat his kids.' I don't

care. That's your opinion. Because you don't know the story. You don't know

what went down. And they're not my kids.

(End of soundbite)

TERRY GROSS, host:

Now in the TV show, the Bernie Mac character is not used to being a father.

Mr. MAC: Right.

GROSS: You know, he just inherited these three kids, and he's making a lot of

mistakes. Now the most quoted line from the show so far is something he says

to one of the kids. You know what the line is?

Mr. MAC: Yeah.

GROSS: Why don't you say it.

Mr. MAC: I'll bust your head 'til the white meat show.

GROSS: That's it.

Mr. MAC: Was that it?

GROSS: Yeah, because his impulse is always like if the kids are misbehaving,

hit 'em.

Mr. MAC: Well...

GROSS: And he doesn't really do it, but that's the impulse.

Mr. MAC: Well, he's from the old school. I mean, he believe that ruling

with an iron hand. And, I mean, you have to understand something. He comes

from a generation, or that time period in the '70s and '60s where spankings

were permitted, and discipline was of the high regard. Bernie Mac has no idea

about parenting. And his way of parenting, he's still a disciplinarian. And

he believes in his heart strongly that a kid should be a kid. And that's

where the problem lies. He's not PC. He's not worried about image. He's

living his life, and he's trying to save lives. And that's what makes the

show so interesting, and that's what makes the humor. The humor's not

punch-line jokes. That's something I didn't want.

GROSS: You grew up on the South Side of Chicago.

Mr. MAC: Yes, ma'am.

GROSS: Describe where you grew up.

Mr. MAC: I grew up--I was born on 66th and Blackstone, and that building was

torn down because it was rat infested. We couldn't play outside because the

rats used to be in the walls, on the bannisters. We stayed on the third

floor, and my mom used to literally pick me up--I was three to four years

old--and she would walk me three flights of stairs and kicking rats from her

feet. The city tore the rat--I mean the building down and moved us to 69th

and Morgan. Well, that was a little bit better supposedly, the Englewood area

of Chicago. And at four years old, that's when I--four to five--decided I

wanted to be a comedian. Because I walked in from playing, and I saw my

mother sitting in her favorite chair crying. And as a little kid I saw her

crying, I began to cry, like most kids often do. And I asked her why was she

crying, and she told me, `Nothing.'

At that particular time, Ed Sullivan was introducing Bill Cosby. Bill Cosby

came out and he did a routine about rats and snakes in the bathroom. My

mother began to laugh and cry at the same time. When I saw that, I started

laughing with her. And I told my mom, I said, `That's what I'm going to be,

Mom. I'm going to be a comedian so I never have to see you cry again.'

Because at that particular time, I thought comedians relieved my mother of her

pain. And that's something that I always wanted to do.

GROSS: So what were some of the jokes that went over real big when you were a

boy?

Mr. MAC: I think none. I think that I was a struggling comic, but in my

mind I was successful. People said I was stupid, I was silly. They said I

was buffoonish. I used to dress up, put on my mother wig, put on my

grandmother slip coat. I'd dress up as a woman and portray as Bernice. That

was one of the characters that I created as a young boy, was Bernice. And it

wasn't about being a homosexual or anything like that. I was portraying a

woman. And I used to talk like a woman, put on my grandmother glasses, and I

used to mimic

(Talking in female voice) `Y'all better quit playing up in here. Everybody

better go to bed. I'm sick and tired of all this mess. Lord, Lord.'

And that's how my grandmother used to talk.

GROSS: Right. Who were the comics you loved to listen to when you were

growing up?

Mr. MAC: Sweetheart, I was a student of the game, I had so many. I mean,

from Richard Pryor, Redd Foxx, Moms Mabley, Pigmeat Markum, Jack Benny, Red

Skelton, Johnny Carson, Steve Allen. Oh, I don't want to leave anybody out.

Jackie Gleason was one of my favorites. Norm Crosby, Don Rickles.

GROSS: What did you do to try to figure out what it is that they did that was

so funny? You said earlier that you tried to do impressions of comics that

you loved when you were young.

Mr. MAC: I watched what made them different. I watched what made them all

successful in their own way. And what made them all successful was style.

They had a unique style about themselves, not like today. You see one comic,

and he gets hot, that's what they want everyone to be like. They want

everyone to be like that individual. Don Rickles--I was so impressed with Don

Rickles, the way he can just come in and just destroy an entire room. I was

so impressed. And I was not offended as a young boy watching this guy and

some of the things--Jews, blacks, Chinese. I mean, he tore you up, but you

knew it was a joke. I got it right away. I was not offended. I was not

saying, `Did you hear what he said?' He was funny.

Jackie Gleason was so impressive to me, whereas he never rehearsed. He

ad-libbed so well, and he took--the energy that he had was something that I

wanted. That's a page of his notebook that I've tested.

GROSS: How did you figure out who you were going to be on stage as a comic?

Mr. MAC: I didn't figure it out until 1987. It's just something that came

to me. I combined them all. Richard Pryor showed me how to laugh at

yourself. That was something that was unheard of, to laugh at your pain.

Redd Foxx was nothing but Richard Pryor, but he was denied. Richard Pryor

modified and moderated Redd Foxx. Redd Foxx made 43-plus albums. That's a

hell of a lot of jokes. But America wasn't ready for Redd Foxx. They said he

was too blue. But Redd Foxx taught me how to be myself. Performing in

Hacienda Hotel in Las Vegas, he told me, he said, `You're a funny guy, but you

don't want to be funny. You want to be liked.' I didn't understand what he

meant at that particular time.

Well, in 1987, I did a show in Chicago, and I was performing and I wasn't at

my best at that particular time, and a heckler kept heckling me. He was

heckling everybody the whole entire night. And it was my turn. Everybody was

really scared to go up, because this guy was a big guy, big red neck. I mean,

he had a table full of cats, and they was just intimidating everybody. Well,

I went up and I was not intimidated, and he said a few words. I kept trying

to do my normal act. I got off my normal act, and I got on him, and the place

went crazy.

DAVIES: Comedian Bernie Mac speaking with Terry Gross in 2001. We'll hear

more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

DAVIES: Today we're remembering comedian Bernie Mac who died on Saturday.

Terry spoke to him in 2001.

GROSS: Now when you were getting started, did you play different kinds of

audiences, some black audiences, some white audiences, some integrated

audiences?

Mr. MAC: I performed wherever there was people. I started on the El's of

Chicago. In the '70s I used to ride the El's and perform from 95th Street all

the way downtown. I used to do the subways.

GROSS: Wait, wait, wait. So how would you do it? You'd just walk into a car

and start doing your act?

Mr. MAC: No, I never walked into a car. No, I never did that. What I used

to do was, during the rush hour, people go to work. I would get on the end of

the El and I would go--and I would watch the news and I would read the paper,

see what was going on in the city. And I would get on, and people would first

look at me like I was a bum, until they got acquainted with me and they got

familiar with me, and they said, `Oh, this guy, this guy, this is the El

comedian.' And I actually made people laugh. And I had a box, and people used

to put money in the box. Then when I got to Lake Street, I used to go way

down in the subway, and as people be going back and forth, I would stand

there, and I had this little microphone, little B box thing, and it was like

my speaker; and I would tell jokes and I would talk about current events,

things that had happened in the neighborhood. And plus I would do little

characters and stuff that I had back then. And people would throw money in

the box. I made 3 to $400 a day.

GROSS: Wow, that's great.

Mr. MAC: But I was not happy.

GROSS: That's probably more than some of the comedy clubs paid.

Mr. MAC: Yeah, but I wasn't happy.

GROSS: Uh-huh.

Mr. MAC: I wasn't happy at all because I felt like I was begging. I felt

like a bum.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MAC: I wanted to be legitimized. In 1977, I went to the clubs.

GROSS: Did you find that white audiences and black audiences reacted

differently to your material, or reacted differently in general?

Mr. MAC: Well, they act different in general, because white audience come to

be entertained; black audience want to entertain you. And white audiences are

more cordial, more respectful of the artist. And even if you're bad, I mean,

you know, the audience has changed. I'm talking about the audience back then.

The audience has changed all the way around the table now. But white audience

was more cordial to you. Black audience are--they just tell you like it is.

If you suck, you suck, and they don't want to hear--you ain't getting nothing

but two or three minutes. You come out the gate with that old sorry stuff,

you in a world of trouble.

GROSS: Now you opened for acts like Gladys Knight, The Temptations, The

O'Jays. What's it like to open for big-name music acts? What were the pros

and cons of that?

Mr. MAC: Well, the pros were that you made it, that you were on your way and

you were pretty good to be there. The cons were, if you believe that stuff,

you was in a world of trouble. You know, that's one reason why I don't hear

the voices. You know, you can be up today and down tomorrow. Comedy is

something that, you know, you have to really, really have in your heart;

something that you just don't wake up and say you want to do or be. Comedy is

something that has to be in your bones, because it's you against the world.

In boxing, you have single activity, but a judge can determine your fate, or a

referee can stop the fight early. Tennis, hey, a bad call here and there can

determine your fate. But comedy, you have no excuses. It's you and the mike,

and a bunch of people who don't give a doggone about you. And then once you

get out there, you're on your own. And that's one thing that I love about

comedy. I love that kind of pressure.

GROSS: You're in the remake of "Ocean's 11," the new versions of it. Who do

you play in it?

Mr. MAC: I play a character of the name of Frank Catton, who's a con man.

I'm the cat that enabled everyone to get into the casinos, because I know the

casinos like the back of my hand. I play as a card dealer. I'm a con man.

But I get the maps and I lay everything out and I get us in and out of all

these casinos. And that's my job.

GROSS: Were you a fan of the Rat Pack, and specifically of Sammy Davis Jr.,

when you were young?

Mr. MAC: Oh, no question.

GROSS: Yeah?

Mr. MAC: No question. Troy Bishop, Peter Lawford. I mean, Sammy, I thought

those cats were--Dean Martin. Dean Martin had a certain suave about him that

was undescribable. And honestly speaking, he sang better than Frank Sinatra.

Frank Sinatra, I could think of a million other cats...

GROSS: No. No way.

Mr. MAC: Oh, please.

GROSS: No.

Mr. MAC: Frank Sinatra's over, overrated to me.

GROSS: No.

Mr. MAC: But I like his persona. I like what he stood for, and I like the

respect that he had. Offstage, his presence was more powerful than all.

Frank Sinatra was mediocre to me. Andy Williams, Mel Torme, Dean Martin tear

his tail up any day. Those are my favorites. And Dean Martin was funny.

Dean Martin had a certain pizazz about himself that was just unbelievable.

Frank Sinatra just had that persona. He had that halo on him that people was

afraid to touch. And there's nothing wrong with that. I think he's very

talented. I love the Rat Pack, but that's just my personal opinion of my

favorite. I can name some more: Perry Como, much better singer.

GROSS: Now you're my guest, so I'm not going to argue with you about Andy

Williams being a better singer than Frank Sinatra.

Mr. MAC: OK.

GROSS: But if we meet on the street sometime...

Mr. MAC: You know what?

GROSS: ...we'll talk more about it.

Mr. MAC: That's a beautiful day.

(Singing) "I got my candy."

Oh, he was all right. He was all right. And I'll tell you what, whenever you

meet me, we've got to debate.

GROSS: You bet. I have strong feelings about Sinatra.

Mr. MAC: I got facts. I'm bringing facts with me.

GROSS: OK. I've got strong feelings about Andy Williams, too. I never

really liked him.

Mr. MAC: OK. That's all right. But he beat Frank.

GROSS: All right.

Mr. MAC: All right, baby.

DAVIES: Comedian Bernie Mac speaking with Terry Gross in 2001. He died on

Saturday at the age of 50. He'll appear in the film "Soul Man" which is

scheduled to be released later this year. In it he plays a soul singer

returning to the stage after 20 years. The film also features Isaac Hayes as

himself.

(Credits)

DAVIES: For Terry Gross, I'm Dave Davies.

(Soundbite of "Soul Man")

Unidentified Singers: (Singing) I'm a soul man, yeah

I'm a soul man

Grab the ropes and I'll pull you in

Give you hope and be your only boyfriend

Yeah, yeah

I'm talking about a soul man

I'm a soul man

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.