Professor Raymond McNally

Professor Raymond McNally, an expert on the many portrayals of vampires in folklore and film, died Oct. 2 at the age of 71. McNally traced the origins of the Dracula story in Transylvania. He wrote the book In Search of Dracula and taught at Boston College, specializing in Russian intellectual life.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on October 23, 2002

Transcript

DATE October 23, 2002 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

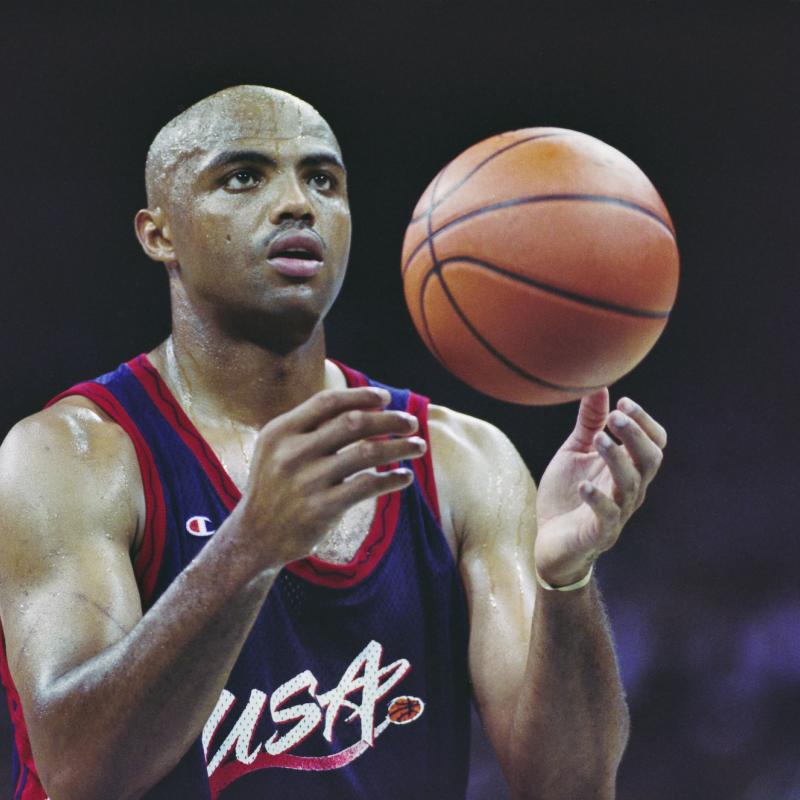

Interview: Charles Barkley discusses his new book, his basketball

career and how the NBA has changed since his retirement

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

During his years with the NBA, my guest, Charles Barkley, was a great power

forward with a knack for saying whatever was on his mind. He played for the

Philadelphia 76ers, the Phoenix Suns and the Houston Rockets before retiring

in December of 1999 after rupturing a tendon in his left knee. He was the

NBA's most valuable player for the 1992-'93 season, his first season with the

Phoenix Suns. He was selected to 11 all-star teams. Now Barkley is a studio

analyst for TNT's "Inside the NBA." Barkley has a new book called "I May Be

Wrong but I Doubt It." His co-author, Michael Wilbon, says about Barkley,

`He's not for the easily offended, those stuck in neutral or those without a

generous sense of humor.'

You've never backed away from saying what's on your mind, and you've never

really worried about toning it down or couching it in diplomatic language.

And your book is filled with interesting opinions. One of the interesting

opinions you give is that you don't like that expression `keeping it real,'

particularly when it's used by someone like Allen Iverson. What's the problem

you have with that?

Mr. CHARLES BARKLEY (Author, "I May Be Wrong but I Doubt It"): Well,

because I'm not sure what it means. Because I consider it a negative

stereotype, because what it's really saying to a black person, when it's used

is, no matter how educated, how successful you are, you can act a certain way,

you're keeping it real, and you really aren't keeping it real, because you

should grow; you should mature. You hopefully to go college, get an

education, get married, have kids, stuff you do when you're young.

Like we all grew up poor. I like Allen Iverson, but Allen Iverson is not poor

anymore. He doesn't live in the ghetto, so for his fans to say if he does

something wrong he's keeping it real, he should take that as an insult,

because he's a husband and a father and a terrific basketball player more than

anything. But to tell black athletes--they only say it about black athletes.

If they get in trouble, they say, `Well, they're defiant. They're keeping it

real.' I take that as a great insult.

GROSS: Let me quote something you say in your book, "I May Be Wrong but I

Doubt It." You write, "It's weird being rich and black because you're caught

between two worlds. Being rich puts you in a predominantly white world, but

you don't just stop liking things about the life you've lived, your old

friends, your old boys. You've outgrown most of them, but you want to

maintain relationships." Can you talk about what that was like for you when

you first became famous and wealthy and you didn't want to cut yourself off

from your past, but at the same time, you wanted to grow and you wanted to

change your life. I mean, heck, your life was changing whether you wanted it

to change or not.

Mr. BARKLEY: You know, it's really unbelievable--I can't even think of the

word I want to use--when you're going through it, you're like--you know, I was

going to college, then you go to the NBA and you see this big, beautiful

world, and then you go back home, you go back to the projects, and your

friends want to--you know, I started playing basketball because I had started

doing some bad stuff. So you can't steal anymore. You can't do drugs

anymore. You can't stay out all night. You gotta train and, you know, you

just have to grow and mature, and you're caught between a rock and a hard

place. And I think the problem a lot of athletes have, and one of the reasons

that I wanted to talk about it in the book, you're caught in between, and you

try to buy your friends. And before you know it--I knew it--you know, I had

lent my friends like a million dollars trying to like be their friends.

GROSS: These are old friends you're talking about?

Mr. BARKLEY: These are old friends. Like I couldn't be with them, so I

tried to buy their friendship to a certain degree by, like, `Well, I can't be

with them because I live in Philly now. I don't live in Alabama anymore, but

I want to keep my friends, so I'll just keep giving them money when I see

them, or sending them money, and they'll still be my friends.' Because what

happens when you finally say, `You know what? I'm not sending you anymore

money,' they stop being your friends. And except for a couple of those guys,

they've all gone and so is my money. So it's really--I don't know if that

happens in the white community--I wrote this book from a black

perspective--but there's a lot of BS that goes on in the black community. And

one of the things I wanted really to talk about in the book was we as black

people, we are never going to be successful until we address our own problems

which are, number one, black on black crime, teen-age pregnancies and

single-parent homes. It's too easy to say, `Well, white people treat us bad'

or `The system is flawed.' We have to start treating each other better, and

that's the biggest problem. We don't treat each other well.

GROSS: One of the issues, I think, for a lot of athletes and actors and music

stars is that if they get famous when they're young, they get a lot of money

at a time when they're not emotionally mature yet. They still have the tastes

of a teen-ager, but they have the money of somebody who's, you know, succeeded

over a long period of time, even though they got that money really fast. And

so sometimes I think people aren't sure how best to use that money, because it

came so quick.

Mr. BARKLEY: Well, it's funny, because I wrote a thing in there about how

Dr. J and Moses Malone influenced my life as far as--and like I said, I wrote

this book from a black perspective. A lot of black people, when the become

rich and famous, they buy a lot of gaudy things, and I did that. I bought

like six cars. And Moses Malone and Dr. J, who really helped me, sat me down

and said, `Think about this. If you put that money in the bank, in 10, 15

years, you'll be able to buy 20 of those cars.' He says, `You don't need all

six of those cars.' This is Dr. J, who really influenced me. He says, `Young

fella, everybody knows who you are. You don't have to buy $100,000 car, 200,

$300,000 cars, like a lot of these young kids do today. You need to put that

money in the bank and let it grow.'

But a lot of guys, a lot of these young kids, when they get their money now,

they buy 10 cars, and they buy as much jewelry and all the crap they can buy.

And that doesn't make them. The person you become is what you are.

GROSS: A lot of players travel with an entourage, just in the same way a lot

of music stars and actors travel with an entourage.

Mr. BARKLEY: First of all, that's stupid when any of them do it.

GROSS: That's what I'm wondering, if like did you have an entourage, or...

Mr. BARKLEY: The entourage is something that--I don't know where it came

from, to be honest with you--never traveled--and as great as Dr. J was, he

never traveled with an entourage, or Moses. You know, it's--Magic Johnson,

Larry Bird. I'm not sure where the entourage thing came from, and it's not

good and never has been good, never will be good.

GROSS: Well, why not? What's not good about it?

Mr. BARKLEY: No other person--you don't bring your girlfriends to work, do

you? And basketball--that's their job. I mean, no other person who goes to

work takes five or six of their friends.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. BARKLEY: I mean, that's just common sense. Like I could see if you are

an actress, you got a hair person, you got a personal assistant, maybe one

person, but a person who travels with five or six people, five or six guys,

that's just stupid.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Charles Barkley. He has a new

book. It's called "I May Be Wrong but I Doubt It."

You've always said that you didn't want to be a role model, per se, and, in

fact, you even made a Nike commercial about that. Describe the commercial.

Mr. BARKLEY: Well, I made a commercial, and what the commercial said, `I am

not a role model. Just because I can play basketball, doesn't mean I should

raise your kids. Parents are role models.' Probably the thing I'm most proud

of out of all the things I've ever done.

GROSS: So whether you want to be a role model or not, you're kind of, at the

very least, an inadvertent role model. So what kind of role model do you

think you've been?

Mr. BARKLEY: I've been just a man. And I've said that. I've done some good

things. I've made some mistakes. But I always keep going. I don't think

anything can stop me as far as what I want to do and what I want to

accomplish.

GROSS: Probably in the mistake category come a couple of the more celebrated

things from--more infamous maybe is the word--from earlier in your career,

like a brawl you got into outside of a bar where you...

Mr. BARKLEY: Yeah, I got arrested about five times for brawling, but I never

worried about those, because I was always acquitted. But if somebody

threatened me--I don't care if you're famous or not, you have the right to

protect yourself. The rest of the things really didn't bother me, to be

honest with you. Somebody threatened me, and I'm going to defend myself. I

didn't worry about going to jail. I didn't worry about public perception. I

would hope somebody who's a fan of mine, or somebody who works for my team,

would not want me to, just because I'm in the limelight, get beat up.

GROSS: So what kind of threats did you face?

Mr. BARKLEY: Just guys saying they're going to kick your behind.

GROSS: To show how tough they are?

Mr. BARKLEY: Yeah. Oh, these always were guys that were drunk. And like I

said, I was always acquitted. It's always--when you get arrested it's in big

letters; when you get acquitted it's in small letters.

GROSS: So give me a sense of how somebody would come up to you and challenge

you.

Mr. BARKLEY: Well, you know what's interesting about that? Every single

night you go out--every single night you go out, there's one jerk. There's

somebody who stands beside you and tells you how much they don't like you, or

they're talking to another person, telling somebody how much they like you.

You move to the other side of the bar, they'll follow you. I mean, every

single night you go out, there's somebody who's trying to start some trouble

with you. But the times I got arrested, guys came up and were saying they

were going to fight me. I hit them, and we hit each other and never lasted

long. I never hurt anybody. They never hurt me. And it's just negative

press.

GROSS: So did you feel like you had to hit them before things got out of

control?

Mr. BARKLEY: I think you have to hit them before they hit you. I mean,

that's just normal. You can't let anybody hit you, no matter how small they

are or how big they are. If you feel threatened, you've got to hit them.

GROSS: Let's talk a little bit about pain. You were kind of famous for being

able to tolerate a pretty high threshold of pain. And you write in your book

that, you know, ever since your early years, you played with a lot of pain.

Did you have like a mental way of refocusing you attention away from the pain?

Mr. BARKLEY: No. You know what it is? To be honest with you, you just want

to play, you know.

GROSS: Uh-huh.

Mr. BARKLEY: Because you know you have a great responsibility there. I

always felt like, `Man, these people paid a lot of money to see me play.

Shoot me up and throw me back out there.' I mean, I took a lot of injections.

GROSS: Cortisone?

Mr. BARKLEY: Yeah. I mean, I've taken a ton; a lot of anti-inflammatories.

I've taken a ton. But I always felt like, `Man, these kids are here, and all

these people paid money to see me play.' I mean, because realistically they

come to see stars play. They might come to see their team play, but they want

the stars to do well. So you always feel, like, that pressure, number one.

But also, you know, there's nothing to me like playing basketball. It's the

greatest job, the most fun in the world.

GROSS: Now when you're performing, adrenaline masks a lot of the pain, and

the focus that you need to play masks a lot of the pain. How about when the

game's over?

Mr. BARKLEY: Well, you pay for it. You pay for it when the game is over and

when your career is over. Like I'm 39, but when I get up in the morning, and

I noticed this my last four or five years, you feel like you're 65 when you

get out of bed in the morning. I mean, it is so--you are in pain. I know I

got arthritis. You know, I got two bad knees; got arthritis in my fingers;

back hurt all the time. I mean, you pay for it when it's over.

GROSS: Do you feel like you made the right choices and that your doctors and

coaches made the right choices in deciding after an injury when it was time to

go back into the game?

Mr. BARKLEY: Well, you have to trust yourself first and your doctor second.

Because what happens is their job is to get you back out there. And I played

on three teams, and we've had some good doctors and some bad doctors. I mean,

I've been on teams where they fired doctors because they wouldn't let the

players play too soon. I mean, you know, I played with a trainer who got

fired because he wouldn't rush players back.

GROSS: Did you ever get into a fight with a doctor or a coach because you

felt you weren't ready yet?

Mr. BARKLEY: Oh, yeah, I had a couple of confrontations. Oh, yeah. You

know, because teams want you to play. I mean, you're their money line. I

mean, they want you to play.

GROSS: My guest is Charles Barkley. His new book is called "I May Be Wrong

but I Doubt It." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcement)

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is former NBA star Charles Barkley. He has a new book called

"I May Be Wrong but I Doubt It."

Now when you joined the Philadelphia 76ers, it was toward the very end of

Julius Erving's career.

Mr. BARKLEY: Yes.

GROSS: And I want to read something that was written in Sports Illustrated in

1988. It said, `After a decade under the leadership of noted NBA diplomat

Julius Erving, the Philadelphia 76ers now march to the unpredictable drum

beat of Charles Barkley, who doesn't have a tactful bone in his wide body.'

So I'm wondering, how would you compare yourself as like a team star with

Julius Erving?

Mr. BARKLEY: Well, it really bothers me when somebody calls me controversial

or opinionated or tactless, because, first of all, I don't think I'm ever

going to say anything else that nobody thought or said before. But if you got

a strong personality, and other people are insecure, they're going to make it

sound like you're a bad person, and I think that's a little bit unfair.

Because I just try to be honest. I would prefer people to say, `Well, Charles

is honest.' If they say brutally honest, that's fine with me. But just to

call somebody--saying they don't have a tact or they're controversial and

opinionated because they don't say what you want them to say, I think that's

biased.

GROSS: So how do you think your style compared as a team leader with Julius

Erving's because he was considered to be--yeah.

Mr. BARKLEY: Oh, I think he was--first of all, he was a great influence on

me, but I'm not like him. I'm more emotional. And I needed emotion to play a

certain way. And...

GROSS: What do you mean by that?

Mr. BARKLEY: My emotion drove me to do well. You know, Dr. J was more

talented than pretty much everybody. No, I needed my emotion and passion to

help me take my game to another level. And I needed it, that's all I can say.

GROSS: Do you think that there were generational differences between you and

Julius Erving?

Mr. BARKLEY: Well, I think there's generational gaps, yeah, between him and

me and between these young guys today. I mean, I think there's always

generational gaps. But you know what? When push comes to shove, it still

always gets back to who plays the best basketball, and I think that it's all

right to be different. I don't like some of the stuff these young guys do,

but I don't think it's bad, all of it. Some of it I think is bad, but not all

of it.

GROSS: What are some of the like basketball differences, generational

differences, that you like or don't?

Mr. BARKLEY: I don't think they play good basketball. You know, a lot of the

young guys think we don't like the way they play because they make a lot of

money. We want them to be successful. We want them to make the game great.

We have a problem with the way they play. I don't know if you watched the

world championship this year when we lost for the first time ever using NBA

players, and we lost because they did not play good basketball. That's the

problem we have with them, they do not play good basketball.

GROSS: What do you think is the problem?

Mr. BARKLEY: Well, they're lacking fundamentals. I think, number one,

they're younger and they haven't had a chance for their game to grow and

mature. But also, I don't think coaches have the discipline to get on them.

I mean, coaches are afraid of players nowadays--high schools, colleges and in

the NBA.

GROSS: In what way do you think coaches are afraid of players, and why do you

think they're afraid?

Mr. BARKLEY: Well, because I think the players make so much money now that

it's a lot easier to fire coaches than it is players. I mean, the money is

astronomical, and God bless them. But it obviously makes it really harder

for--it if comes down between players and coaches, which it always does at

some point, the coach is gone.

GROSS: Do you think there's a respect thing coming into play now in a way

that it didn't before? For instance, when Allen Iverson's coach criticizes

him, Iverson can say, `He disrespected me.'

Mr. BARKLEY: well, I think it's--you know, see, that's the thing. None of

these guys--I shouldn't say none, but I'm being a little bit facetious. None

of these guys could have played in the old days. You know, every time--and

that was one of the things--anytime you see a coach criticize a player now,

the player feels like he's disrespected. In the old days, coaches yelled and

cursed at you all the time, and it was like done to make you play better. And

all these new guys, they take it as disrespect. They couldn't have played in

the '60s, '70s and '80s, because it was like yelling and screaming was part of

the whole thing.

GROSS: Charles Barkley. His new book is called "I May Be Wrong but I Doubt

It." He'll be back in the second half of the show.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Coming up, we listen back to an interview with Raymond McNally, who

wrote several books about Dracula and vampire lore. He died earlier this

month at the age of 71. Also, we continue our interview with former NBA star

Charles Barkley.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Back with former NBA star Charles Barkley. He was the NBA's Most Valuable

Player in 1993. He played for the Philadelphia 76ers, the Phoenix Suns and

the Houston Rockets before retiring in 1999. Throughout his career, he was

famous for his outspokenness and controversial opinions. He'll offer some of

his opinions in his new book, "I May Be Wrong but I Doubt It."

You grew up in Leeds, Alabama. Where is that, what kind of place was it to

grow up?

Mr. BARKLEY: Leeds is just a typical Southern small town with one stoplight

and everybody knows everybody, no McDonald's. You know, I always say if...

GROSS: Still? There's still no McDonald's.

Mr. BARKLEY: We got our McDonald's now. We do now. But it's weird, I always

say if--you can always tell how small your hometown is if you got a Dairy

Queen and stuff, a McDonald's, or your steakhouse is a Sizzler. You can

always--if you live in a small town, you're going to have those two things, a

Dairy Queen--you're not good enough for a Ruth's Chris or a Morton's or a

McDonald's so you're going to have a Dairy Queen and that's it, and a Sizzler.

GROSS: Anything you liked about growing up in a small town?

Mr. BARKLEY: I did like it because I didn't have to deal with all the

distractions a lot of these kids in big cities have to deal with. I think

there is a big difference growing up in a small town than a big city. And I

really enjoyed growing up there.

GROSS: Your father left your family when you were a baby, I think. So you

were raised by your mother and your grandmother. You say your grandmother was

the disciplinarian in the family. What was her approach to disciplining you?

Mr. BARKLEY: If you didn't do right, she'd beat you down. I mean, it was

very simple. She ran a tight ship. Because my mother was a maid and my

grandmother worked at a meat packing factory and that was a--like my

grandmother was like the father figure. She was really strong. She was

really disciplined. And I really enjoyed--I really enjoyed--I love my

grandmother to death. She's probably the most influential person in my life,

and it's just been a great deal for me how she took care of me.

GROSS: You say she beat you--With what?

Mr. BARKLEY: Switches. Those are tree limbs, would be the best way to

explain it. But they were good. It taught me a lot. I think kids should get

disciplined.

GROSS: Well, most people now think that that's like child abuse.

Mr. BARKLEY: And that's why kids are crazy now. See, I think kids were

better back in that day. You know, we can't discipline kids anymore because

every time you do anything to them, it's considered child abuse, but if you

look at it realistically, kids were much better behaved back then than they

are now.

GROSS: Did you beat your kids with switches?

Mr. BARKLEY: I have a daughter who i--she gets spanked. But she's a good

girl. She's a great girl. But if I had to, I would.

GROSS: But you didn't?

Mr. BARKLEY: I have not.

GROSS: OK. You say your family sold bootlegged alcohol to supplement the

income. Did you ever taste it?

Mr. BARKLEY: Oh, yeah, many times.

GROSS: How was it?

Mr. BARKLEY: Nasty. It was nasty. You know, that's one of the things why I

have to give great admiration and respect to my mother and grandmother.

Because, you know, they were just trying to make ends meet. And every weekend

we had a card game going on but that's actually like--that's your

responsibility when you're a parent. Your job is to find a way to take care

of your kids. And it made me appreciate them more because they were willing

to--they were scrubbing floors and my grandmother in the meat factory and that

wasn't enough. They were like doing anything to make ends meet. And that

make me appreciate and respect them even more.

GROSS: How did you start playing basketball?

Mr. BARKLEY: I started playing basketball when I was nine. I started playing

because I started getting into trouble. You know, I started stealing, staying

out late and things like that.

GROSS: What were you stealing?

Mr. BARKLEY: You know ...(unintelligible) kind of weird, CD--not CDs--like

music. And you know the thing that was stupid, we would steal stuff that we

didn't even need like pens, pencils.

GROSS: Because they were easy to steal?

Mr. BARKLEY: Because we were just bored. I mean, just because we were bored.

And that was not what I wanted to do. And one night the police was chasing

us, and I made up my mind that night, I said, `I'm going to go play

basketball. I got to do something to stay out of trouble.' Got to. Because

that's not the life I want to lead.

GROSS: So did you realize right away that you were good?

Mr. BARKLEY: No, I wasn't any good in the beginning. I wasn't actually--at

the time, I'm nine; I wasn't any good until I became a senior in high school.

That's the thing that's unique and ironic. I wasn't any good in high school.

GROSS: Did you have a particularly good coach when you were a senior?

Mr. BARKLEY: We had a really good team and a good coach, but I grew from

5'10" to 6'5" in one year.

GROSS: Wow. That's a lot in one year.

Mr. BARKLEY: Yeah. And that made a big difference, obviously, in my talent.

GROSS: Did you see yourself going from being really tall to being

comparatively short in the NBA?

Mr. BARKLEY: I did. Well, you notice at first in college. Because in

college, you know, there's a lot of big guys in college, a lot of guys who are

tall. And you go from like being the big man on campus, heightwise, to like

the shortest guy on the team. So, yeah, it is somewhat mind-boggling. You

just have to work harder.

GROSS: OK, in college, you had the reputation--you were considered heavy

compared to the other players. Right? And you had nicknames.

Mr. BARKLEY: Is heavy and fat the same thing?

GROSS: I don't know.

Mr. BARKLEY: Yeah, I was a big boy in college.

GROSS: I thought fat would maybe sound too heavy, but...

Mr. BARKLEY: That's--got to have tact.

GROSS: Yeah, I was just trying to figure out which sounded more tactful,

heavy or fat?

Mr. BARKLEY: Yeah. Yeah. You know, I was fat in college.

GROSS: Well, what did fat mean? I mean, how--what did...

Mr. BARKLEY: I weighed about 300 pounds.

GROSS: But you were 6'4" so...

Mr. BARKLEY: Yeah. But I was 300 pounds. I was like a little roly-poly.

But, you know, I loved to play.

GROSS: It must have been hard to jump if you were heavy.

Mr. BARKLEY: No, it was easy to jump. I always had the talent. Well, I

don't know if I always had it, but I had it at that time. But I just loved to

play and jumping was easy.

GROSS: So did it get to you when people ribbed you and called you nicknames?

Mr. BARKLEY: No, it motivated me.

GROSS: What were some of the names?

Mr. BARKLEY: Breadtruck, fatboy, blimpy, it's pretty--I use all that stuff

as motivating. You know, because you want to show people you can do it and

there's nothing better than succeeding. That's the thing I try to stress to

kids, there's nothing better than succeeding.

GROSS: Now apparently some fans would send you pizzas delivered to the bench

when you were in college.

Mr. BARKLEY: Oh, yeah, they had a lot of problem with that when I would play

on the road. There'd always be--not always, but probably five or six times

when I was in college, they'd order pizza for me and just kept calling my

name. It was fun. I had a good time with it. I was never bitter or

resentful about my nickname. Because it got me a lot of publicity, number

one, but also I'm able to laugh at myself anyway.

GROSS: Did you ever eat the pizzas?

Mr. BARKLEY: No.

GROSS: In case they were spiked?

Mr. BARKLEY: Too close to game time.

GROSS: No, I was thinking you could save them for after the game but then, of

course, they'd be cold.

Mr. BARKLEY: No. Yeah.

GROSS: You play a lot of golf. Did you always like golf? Did you ever look

down on golf?

Mr. BARKLEY: You know, golf is one of probably the most amazing sports in

the world, because once you start playing, you're addicted to it. But I

thought it was the most stupid sport in the world when I saw it on television

when I was little. But then I was like--one of my teammates, Andrew Toney,

told me to try it one day. And then it becomes like a battle of trying to do

better at it. I mean, that was the thing. You know, you're trying to do

better at it. And I love it. I try to play every single day and I love it.

GROSS: Now one of the things people make fun of with golf is the kind of

suburban golf fashions of the pastel pants and the white belt and the pastel

shirt and the white golf shoes. So I'm sure you don't wear that when you're

golfing.

Mr. BARKLEY: You know, I thank God for Tiger Woods, number one, because he's

a great golfer, but he's definitely made improvements in the fashion. I mean,

he's definitely made improvements in the fashion. He's single-handedly

changed the entire golfing dress for eternity. But that's the thing, I think

Tiger should be recognized for more than just playing golf.

GROSS: What else do you do to keep in shape?

Mr. BARKLEY: I work out a lot. I mean, I do. I mean--because you know why?

Because I look at my weight problem is like the Taliban. You can't kill it.

You can't kill it. You know, it's like a constant struggle as you get older

to stay skinny and it's like the Taliban, it just won't die.

GROSS: Now does working out help with the arthritis and with the other aches

and pains that you have from your career in basketball? Or does working out

aggravate that?

Mr. BARKLEY: Well, it probably aggravates it. But it won't aggravate it as

much as me being fat. You know, I mean...

GROSS: Right.

Mr. BARKLEY: ...you got to try to reach a happy compromise. I mean, you got

to reach a happy compromise. I mean, because, like, I can't be fat. I mean,

I joke around with my friends. `I'm too good-looking to be fat.' I mean, I

don't want to be fat.

GROSS: How much do you play basketball now? I know now you have an injury so

at the moment you're not playing at all.

Mr. BARKLEY: I don't play--you know, I might have played once or twice a

year, just screwing around. But I miss it.

GROSS: Charles Barkley, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. BARKLEY: Oh, you're welcome. And it was a terrific--I enjoyed the

interview. Because I enjoy speaking for myself. I'm intelligent enough to

speak for myself. I get tired of doing interviews where a guy will talk to me

for five minutes and then put three seconds on television. And you're, like,

you can make anybody sound like an idiot in that scenario. And that's why I'm

excited to get--because on my new show--and the book gives me a chance to

speak for myself, but also with the new show I have coming, I'm going to give

other newsmakers an opportunity to speak for themselves and that's what--you

know, because these people are a lot smarter than people realize. And thank

you.

GROSS: Thank you. Charles Barkley's new book is called "I May Be Wrong but I

Doubt It."

Coming up, we remember an expert on the Dracula story and vampire lore,

Raymond McNally.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Profile: Remembering Professor Raymond McNally, an expert on

the many portrayals of vampires in folklore and film

TERRY GROSS, host:

The Dracula story has spooked generations of readers and filmgoers, tapping

our fears of contagion and death. Raymond McNally devoted much of his life to

studying the story of Dracula and other vampire legends. His books include

"In Search of Dracula" and "The Essential Dracula." He had been the president

of the International Dracula Society, and he discovered the original Castle

Dracula while traveling through Transylvania in 1967 on a Fulbright research

grant.

Earlier this month, the month that ends with Halloween, McNally died of cancer

at the age of 71. We're going to remember him by listening back to an

interview we recorded in 1985. I asked him according to the folklore, who

becomes a vampire?

(Soundbite of 1985 interview)

Professor RAYMOND McNALLY (Author, "In Search of Dracula"): Well, according

to the folklore, it's a little complicated. Someone who's a werewolf, a

werewolf is someone, of course, who believes that he or she has become a wolf.

A werewolf can become a vampire upon death, anyone who's led a violent life.

In the Christian civilization, children who die unbaptized. Then the seventh

son of a seventh son is doomed. So that's--or, of course, the usual way is if

a vampire infects you during life. And that occurs in a very specific way.

It's not the way it is in the movies, you know, the bite on the neck and that

sort of thing. The vampire must mix his or her blood with yours. You must

drink the blood of the vampire so that your blood content changes, and so when

you die, you will become united with that vampire.

GROSS: Is there any pattern in the folklore to who the vampire's likely to

use as his prey?

Prof. McNALLY: Definite pattern. It's a very important question, too,

because vampires never generally attack strangers. They always attack members

of the immediate family or those with whom they have been intimate in life.

Only after they have taken care of the immediate family and friends and lovers

and so on do they branch out. Now what goes on there is something

psychologically very, very profound I think. If someone you love dies, you

don't want them dead, do you? If you really love them. You're sorry they're

gone. You wish they were back with you. It's a very, very old tendency, you

know. So there is this immediate wanting to have them back, you see, so that

when, in their minds anyway, this person comes back from the dead, the initial

reaction is, `Wow! How great to see you. Wonderful, you know. I'm so happy

you're not dead. You're back.' Then, though, comes the fear. What is that

creature going to be like who has gone through the experience of death? Will

it be as human as we are or will it be something different? And will it, of

course, try to lure us into communion with it? And we know what that means.

The only way you can join together with someone who has died is to become dead

yourself.

GROSS: There's a lot of religious imagery in vampire folklore.

Prof. McNALLY: Yes. It's a kind of Antichrist figure, this vampire. Why?

Well, first of all, it promises what all of us who love life want, eternal

life. But, of course, eternal life, we don't want that and if we're going to

get old, do we--who wants that? Right? You want eternal life where you can

remain physically young and that is the promise, the great promise: physical

immortality and to remain young and healthy. So there's that element. And

the ceremony itself. You know, what are the two great taboos in modern

civilization? One is we do not eat human blood anymore. And we do not eat

human flesh. Those are taboo. However, in several major religions, this is

done symbolically. You become one with the divinity by doing what is

technically taboo. You drink the blood of the savior and you eat his flesh.

You commit vampirism and werewolfism. And you join. It is Communion. Well,

this is a kind of unholy communion. You drink the blood of the vampire, you

become one with the vampire, you acquire physical immortality, at a great

price. But, of course, immortality, usually there's a price tag attached to

it. So what I think the appeal of the story is, say, `Oh, wow. To live

forever and to be young, wonderful,' but then sour grapes.

GROSS: Have you ever come across a story where you suspected there might be a

real vampire in the classical undead sense?

Prof. McNALLY: Yes. One. When I was in Transylvania, I was at the foot of

Castle Dracula and I met a woman there. Her name was Tinka(ph). She's one of

the local villagers, and she told me that her father had died. This was 30

years before. She was telling me about something that happened 30 years

before when her father died. And he was laid out to rest, and in that part of

the world, as in other parts of the world, they keep the corpse in the house

for two, three days before they put it in the ground. They noticed after

three days that the skin was still pliable. Rigor mortis had not set in. And

the cheeks bore a ruddy complexion, so the blood hadn't calcified. Signs of

the vampire, the undead. So she told me, she knew what had to be done but she

couldn't do it, because, after all, it was her father's body and she couldn't

bring herself to do it. But the villagers went ahead and did it and they did

what is done in all the horror movies. They drove a wooden stake through the

corpse and then as an added insurance they burned the body.

GROSS: Are there still places like Transylvania where the legends are

circulating and people still live in fear of it?

Prof. McNALLY: Oh, yes, definitely. I visited place--with members of the

Institute of Folklore, I went up into the mountains with a tape recorder

and we sat down with the peasants and, if you do it correctly--you have to

talk about the crops, you know. You can't just walk up to peasants and say,

`Hi. How about vampires,' or something. A peasant will lie to you. And

peasants are not stupid. It's a wrong assumption on the part of many city

people, you know, who say, `Well, these stupid peasants.' They're not stupid.

They're very clever oftentimes. You have to get their confidence. You talk

about the peaches and the cows and all and then you start asking a little bit

about, `Well, what do you know about the history of this place and so on?

Have you ever heard anything like a walking dead, an undead?' And then they

will open up once they know you're not making fun of them. And the belief is

very much alive there.

GROSS: Raymond McNally, recorded in 1985. He died earlier this month at the

age of 71. His books include "In Search of Dracula" and "The Essential

Dracula." This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: New book "The Little Friend" an interesting yet vexing

novel

TERRY GROSS, host:

With the publication of her first book, "The Secret History," Donna Tartt was

acclaimed a literary phenom. Ten years later, her second novel, "The Little

Friend," has just been published, and critic Maureen Corrigan says Tartt is no

one-hit wonder.

MAUREEN CORRIGAN reporting:

Apart from its many, many dazzling virtues, "The Little Friend," Donna Tartt's

long-awaited second book, has to be one of the most vexing novels ever

written. After finishing it, I kept mulling over the last pages and, indeed,

Tartt's very integrity as a storyteller. Like legendary escape artist Harry

Houdini, who's a guiding presence in this tale, Tartt, at the last possible

moment, slips out of the narrative knots she so elaborately tied throughout

this novel.

It's a breathtaking performance, but a heartless one. I say that because as

my late-night wrestling match with the story illustrates, while Tartt is

slipping her own knots, she's simultaneously tying the distracted reader up in

conundrums and frustrations, closing the covers of the novel and sinking it to

the bottom of a muddy lake.

One of the first bold moves that Tartt performs here is to whisk her readers

far away from the elite New England academic world she made familiar in her

amazing debut, "The Secret History." If that novel was Tartt's homage to 19th

century British Gothic writers, like Mary Shelley and the Brontes, in "The

Little Friend," Tartt does Southern Gothic.

"The Little Friend" is set in Alexandria, Mississippi, in the early 1970s,

where ghosts of plantations and the Civil War linger and memories of more

recent evils possess the present-day inhabitants. The book opens by

dramatizing one such horror. On a chilly spring Mother's Day afternoon, a

nine-year-old boy named Robin is playing outside with his two sisters,

four-year-old Allison and baby Harriet. His mother, who's occupied with a

houseful of relatives, feels a dreamlike flash of panic and rushes outside.

At first, all seems in order. Then the mother sees her son hanging dead from

the black Tupelo tree in their front yard, his pet cat crouching on a branch

above, playfully batting his hair.

Twelve years later, Robin's murder, for that's what it's deemed to be, remains

unsolved. His mother and two sisters still live in the same house, supported

by the attentions of a fairy tale matriarchy of four aged aunts. Tartt tells

us that Allison, now 16, was the pretty one, though all her grace was in her

vagueness. Tartt proceeds to introduce 12-year-old Harriet in two simple

sentences that, in combination, are thrilling. Harriet, the baby, was

neither pretty nor sweet. Harriet was smart. Those two sentences invoke a

powerful literary lineage of wise girls, like Scout from "To Kill a

Mockingbird" and the juvenile versions of Cathy and Jo from "Wuthering

Heights" and "Little Women" respectively.

A couple of grotesque events spur Harriet to actively consider the mystery of

Robin's murder. She decides that a lowdown schoolmate of his, named Danny

Ratliff, was responsible and, with her best friend Hely, a boy, as her

ally, she sets out to exact justice. What follows is a chilling expedition,

not unlike that undertaken by one of Harriet's heroes, the doomed polar

explorer Captain Scott. By the time her mission is over, Harriet, like Scott,

will become viscerally acquainted with the white-out terror of nothingness.

Such an ambitious literary adventure is bound to get stuck in a snowdrift or

two. I could have done with about 75 pages less devoted to the Ratliff clan,

who struck me as a flat reincarnation of Faulkner's Snopes and once was

enough with them. Tartt's equally distasteful obsession here with nature red

in tooth and claw, particularly with snakes, lots of slithering, slimy,

sickening snakes, claims way too much of her descriptive powers. But, oh,

those descriptive powers.

Tartt grants her characters the complexity of change and frailty and she

ferrets out the profundities lurking in the wispiest scraps of experience.

About Robin's postmortem influence on Harriet and Allison, she says, `His

younger sisters, who had never in any proper sense known him at all,

nonetheless grew up certain of their dead brother's favorite color, red; his

favorite book, "The Wind in the Willows"; and his favorite character in it,

Mr. Toad; and a thousand other things which they, being living children and

preferring chocolate ice cream one week and peach the next, were not even sure

they knew about themselves.' Consequently, their relationship with their dead

brother was of the most intimate sort. His strong, bright, immutable

character shining changelessly against the vagueness and vacillation of their

own characters. And they grew up believing this was due to some rare angelic

incandescence of nature on Robin's part and not at all to the fact that he was

dead.

With writing this great, no wonder readers like me will allow ourselves to get

suckered in, cinched tight and then left to struggle all on our own against

Tartt's inexorable finale.

GROSS: Maureen Corrigan teaches literature at Georgetown University. She

reviewed "The Little Friend" by Donna Tartt.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.