In 'Operation Filmmaker,' an Unscripted Outcome

Actor Liev Schreiber had what he thought was a good idea: He'd reach out to a Baghdad film student, offering him an internship on a shoot. But as Nina Davenport's documentary proves, good intentions don't always end in good outcomes. Critic-at-large John Powers has a review.

Contributor

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on June 17, 2008

Transcript

DATE June 17, 2008 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

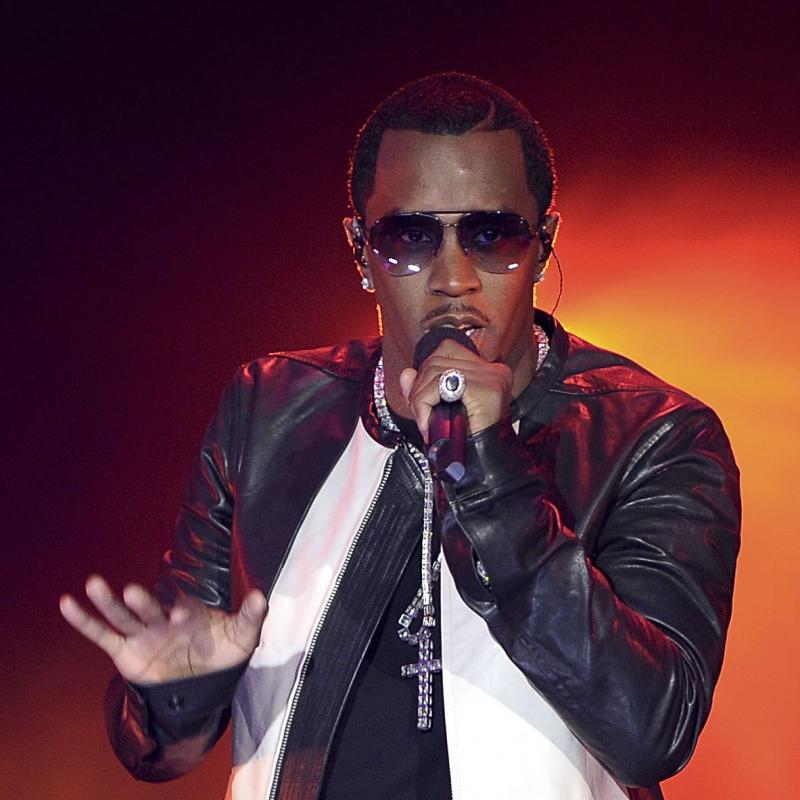

Interview: Sean Combs discusses his life, childhood and career

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest is Sean Combs, aka Puffy Daddy and P. Diddy. He's one of the most

successful and wealthiest people to have come out of the hip-hop world. He

started as a record producer working with performers like Mary J. Blige and

Biggie Smalls. In 1991, he started his own label, Bad Boy Records. Several

years after producing hits by others, he started recording his own music. He

still works in the music world and has an MTV reality show called "Making the

Band." He also has his own design company, Sean John, and has won the fashion

world's equivalent of the Oscar. But he seems especially interested in his

acting career. He made his screen debut in the 2001 film "Made," which was

quickly followed by his role as a prisoner on death row in "Monster's Ball."

In 2004, he starred in the Broadway revival of Lorraine Hansberry's play, "A

Raisin in the Sun." The original 1959 production was the first play on

Broadway written by an African-American woman. Combs' role, Walter, was

originated by Sidney Poitier. This year a movie adaptation of the revival

with the same cast debuted on ABC TV. It's now out on DVD.

Let's start with a scene from it. The story is set in an inner city

neighborhood in the 1950s, in a cramped home that houses Walter, his wife,

their son, Walter's sister, Beneatha, who's in college, and Walter's mother.

The mother is retiring from her job as a domestic because her late husband's

life insurance money is on the way, $10,000. She wants to buy a house with

it. Her daughter wants to use it for medical school. Walter, who hates his

job as a chauffeur, wants to use the money to become a partner in a liquor

store with a couple of guys he knows. His mother is dead set against that

idea and overrules him. In this scene, he's angry and frustrated and trying

to change her mind. His mother is played by Phylicia Rashad.

(Soundbite of "A Raisin in the Sun")

Mr. SEAN COMBS: (As Walter) Mama, I want so many things. Mama, I want so

many things it's kind of driving me crazy.

Ms. PHYLICIA RASHAD: (As Lena) What is it that you want, baby? You got a

nice wife, a fine boy. You got a job.

Mr. COMBS: (As Walter) A job? A job, mama? Mama, I open and close car

doors all day. I drive a man around that looks right through me. I say,

`Yes, sir,' `No, sir,' `Shall I take the drive, sir?' `Am I the best trained

monkey you ever seen, sir?' Mama, that ain't no kind of job. That ain't

nothing. Man, why do I even think you going to understand me?

Ms. RASHAD: (As Lena) Understand what, baby?

Mr. COMBS: (As Walter) Mama, sometimes when I'm driving that man around, and

we passing them cool, fancy restaurants, and these white boys, these white

boys, they just be in there talking about things, important things. They

closing million-dollar deals; I know they are. And, mama, these white boys,

they don't look much older than me.

Ms. RASHAD: (As Lena) So once again it's money.

Mr. COMBS: (As Walter) Yes, it's about money. Because money is life.

Ms. RASHAD: (As Lena) "Money is life"? I remember a time when freedom used

to be life. But now it's money? Have times changed that much?

Mr. COMBS: (As Walter) No, they haven't changed. It's always been about

money. We're just never allowed to get close enough to see it.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's my guest, Sean Combs, and Phylicia Rashad in a scene from the

ABC movie adaptation of "A Raisin in the Sun." They also starred in the

Broadway production.

Sean Combs, welcome to FRESH AIR.

Mr. COMBS: Thank you for having me.

GROSS: And congratulations on the success of "A Raisin in the Sun" on

Broadway and on TV.

Now, you've said that you understand the character that you portray in "A

Raisin in the Sun" because you grew up with three women in the house, your

mother, your grandmother and your sister. Walter, your character, feels that

his mother is still leading the family and that she's depriving him of his

chance, his chance to be the head of the family and also his chance to do what

he really wants to do, to take the chance that he wants to take. Did you ever

feel that your mother was holding you back from things that you wanted to do

or trying too hard to kind of keep you down the straight and narrow?

Mr. COMBS: Unlike Walter, the role that I played, you know, my mother, she

didn't do that. So I had to kind of reach back and kind of related myself

mentally for another relationship of just other people in my life that, you

know, you know, just didn't really have faith in me and didn't believe I could

do it and, you know, the times where I was, you know, pleading with them to

give me a chance to understand. It was something I was able to really, you

know, relate to other relationships in my life. But, no, my mother, on the

contrary, my mother was extremely supportive and being that I lost my father

when I was three, I had to step up, you know, to be the man of the house, and

she welcomed that.

GROSS: You are so associated with wealth. I mean, you are, as everybody

knows, a very wealthy man, one of the wealthiest to come out of hip-hop. What

did you relate to about this scene? And I'm wondering if you aspired to have

a lot of money when you were young, if that was important to you?

Mr. COMBS: I mean, what I related to the scene was that, you know, wasn't

that long ago, even though, you know, I've been blessed to have some success,

it wasn't that long ago where, you know, I didn't have any money in my family.

We didn't really have any money, and we were just working and making ends

meet. So like that understanding of being at that place, you don't all of a

sudden, you know, lose that feeling because, you know, you've been successful

for a couple of years. You know, when I was growing up, no, money wasn't, you

know, everything to me, and I think that's one of the reasons why I attribute

my success to the fact that my motivation was to be the best that I could be

in whatever I was doing, and I felt that if I did that, then I would be

rewarded, and money would be just one of the parts of the rewards of it. And,

you know, as far as understanding, you know, where the character was coming

from, the movie is about that money is not everything in life, that your

family is the most priceless gift that you could have, their support and their

love. But it definitely touches on the fact that money is a part of life.

That's something that, you know, we can't get away from.

GROSS: You know, you replicated the stage set of "Raisin" when you were doing

it on Broadway at home during the rehearsal period so that you could rehearse

at home on the set.

Mr. COMBS: Yeah

GROSS: How did that help you, being at home alone on the set?

Mr. COMBS: You know, for me it really was that, you know, I was such an

inexperienced actor, I was so young in my career, and yet I took on this role

following in the footsteps of Sidney Poitier, so it was, you know, huge shoes

to try to fill. And so I wanted to, you know, be as prepared as I can be

without having any experience onstage ever as an actor, and no experience in

live theater. So I always, you know, practice or rehearse as hard as I can,

but the thing about working on Broadway, they have unions And so the unions

would kick me off the stage because I would want to rehearse too long. So

then I came up with the idea, `OK, if they're going to kick me off the stage,

I still have to figure out a way to rehearse and prepare for the role.' So I

just moved all the furniture out of my living room, which was like the similar

size to the stage on Broadway, because the stages are not really that big, and

I replicated the stage in my house. So after I would go home from rehearsal,

I would still be able to rehearse, and I would, you know, get a couple of my

friends from acting school, you know, and I would have them run the lines with

me.

GROSS: So you hired somebody to replicate the set?

Mr. COMBS: You know, I had, you know, I befriended somebody at the stage,

and you have to understand, it was a modest home. It was like a beat up couch

and...

GROSS: Right, right.

Mr. COMBS: ...you know, a sofa and a coffee table. It wasn't really hard.

We just went to the thrift store and replicated it. And, you know, when I'm

doing something I really go all out. I'll do whatever it takes to be

prepared.

GROSS: Now, your character of Walter is a chauffeur in the movie. Was your

father a chauffeur or a limo driver?

Mr. COMBS: Oh, yeah, no, my father did at one point, he did drive a limo and

then he owned the service. So he had started out as a driver, and he was an

entrepreneur himself and started out as an entrepreneur and then he wound up,

you know, owning the limousine service.

GROSS: Mm-hmm Now, I also read that he worked for--that he was associated

with Frank Lucas, the Harlem drug pin who was...

Mr. COMBS: Yeah.

GROSS: Who the movie "American Gangster" was based on.

Mr. COMBS: Yes. Yeah.

GROSS: That's the character that Denzel Washington played in it.

Mr. COMBS: Yeah. Yeah, there was a time where I guess they had some

dealings together because my father, you know, he was in the streets, and he

was a hustler, or you can call him a gangster. And he chose that life. And,

you know, my family, we've had to pay for that decision because he got killed

when I was three. So, you know, it's just the way the story goes when you

choose that type of lifestyle. But, you know, I understand, you know, why in

his head he was doing what he was doing. He was trying to, during that time,

provide a better life for us. And, you know, it was just the wrong decision.

GROSS: This was in 1972 when he was killed. He was 33. You were, I think,

three years old.

Mr. COMBS: Yeah.

GROSS: Do you have any--that's really early to have memories--do you have any

memory of your father or any memory of his getting shot and killed?

Mr. COMBS: No, I don't really have--I only have like, you know, brief, like,

glimpses of, you know, him like throwing me in the air, but, besides that I

don't, no, really have any recollection of my father. But, you know, I do

feel like, you know, because, you know, the way he lived his life, it kind of

ensured that I would live my life this way, the right way.

GROSS: What did your mother tell you about your father and his death?

Mr. COMBS: When I was growing up, my mother told me that my father had died

in a car accident, and it wasn't like she was telling a total lie. She was

trying to protect me because we were still living in Harlem, but he kind of

did because he got killed in a car, and I guess that's the way she kind of

relayed it to like soften it up for me. So that's, you know, God bless her

for trying to like, you know, trying to like spare me the truth.

But as I got older, I kind of figured it out because just growing up still in

the streets, if anything would happen to me, like my bike was just stolen,

then it would miraculously show up. Anytime anything, you know, would happen,

everything would always be taken care of or whoever was the, you know, the

neighborhood guy that ran the area, he would always tell me that he used to

work with my father. So I was like, `Why does it seem like every, you know,

gangster worked with my father?' So I kind of just put two and two together,

and when I got to Howard University, I went to the library and started doing

research on my name, and then I saw like all of the press clippings from the

funerals and the murder and everything like that.

GROSS: What a way to find out.

Mr. COMBS: Yeah. I kind of always knew, though, you know. I kind of like

had a feeling, so it wasn't like I was sitting, you know, in the library and I

was devastated. If anything, it was a relief that I finally found out, you

know. I was kind of upset with my mother for like a second, but then, you

know, a couple seconds later, I really realized why she was trying to do, is

she was trying to make sure that I didn't, you know, follow in those footsteps

because, you know, where I grew up at, it would have been a natural thing for

me to follow in his footsteps, and also it would have been a natural thing for

me to get started because everything felt like they owed him something.

GROSS: My guest is record producer, rapper, fashion designer and actor Sean

Combs, aka Puff Daddy and P. Diddy. He stars in the recent ABC movie

adaptation of "A Raisin in the Sun." It's just come out on DVD. We'll talk

more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Sean Combs, and as I'm sure you

know, he's a hip-hop star, a producer, fashion designer, entrepreneur and

actor. And he was in a Broadway revival of "A Raisin in the Sun," and that

same cast made an ABC movie of "Raisin in the Sun," and that movie just came

out on DVD.

Now, correct me if I get any facts wrong here, but you grew up in a Harlem

housing project until you were about 12, and then you and your mother moved to

Mount Vernon, which is just north of New York City. Compare the two

neighborhoods for us.

Mr. COMBS: Well, see, I lived at Harlem, so it was, you know, it's a whole

different type of inner city feeling. It's like it helped make me what I was

today. It's so soulful. It's just a place that's like, you know, rich in

culture and soul and, you know, fashion and music, you know. Everybody is

trying to be the best dressed person in the neighborhood. People dance in the

streets. Like growing up in some places, you know, like in the suburbs, kids

grow up playing little league and, you know, and sports. In Harlem, you grow

up dancing and singing and in the world of fashion, just trying to, you know,

put your outfits together. And so it kind of shaped and molded me for my

future.

And the difference of the suburbs, it gave me like that balance, gave me that

other side of things. I was able to grow with different races and, you know,

also get exposed to like trees and grass and things that a lot of us take for

granted, you know, you know, and being able to really actually play, you know,

sports in some grass and not just on the street, you know. You know, it was

the best of both worlds.

GROSS: Your mother sent you to a private Catholic boys high school.

Mr. COMBS: Yeah.

GROSS: Did you want to go to that school?

Mr. COMBS: Oh, no. I wanted to go where the girls were at. But she knew

that that would just--when I was a child, I always had loved women, just

growing up with women. But, you know, she knew that that was probably going

to be a big distraction for me. My whole life, I went to private school and

Catholic schools. I was an altar boy, you know, before, you know, I went to

high school and stuff like that. So I was kind of used to the nuns and the

priests and everything, and just going to school with that type of, you know,

strictness. So I wasn't worried about that, but I at least thought that when

I got to high school, I was going to get to be around some girls. But that

didn't happen. So by the time I got to Howard, you know, Howard University

and I was finally around some young ladies, I was extremely happy.

GROSS: You dropped out of Howard University to be an intern at Uptown

Records, and you became a vice president in your early 20s. How did you know

you wanted to be in the music industry?

Mr. COMBS: Oh, I was looking at like the--there was two people that would be

in the neighborhoods that really were the guys we would look up to, and that

was either the guy, the street hustler, or, you know, the up and coming like

rap star. And so I felt like--I wanted to be a football player, or--to back

you up a little bit, I wanted to be a football player, but I broke my leg. So

then by default, then I wanted to become like a businessman or, you know, I

had a dream to be, you know, in the music business as an artist or just in the

business. And, you know, I would be casted for music videos because I was a

good dancer, and they could come into the clubs and they would just come get

you out of the clubs and offer you a chance to be in a music video. I used to

get chosen a lot, and I used to always see the recording artists, but then I

would see this other guy that looked like he had, you know, more power and

more respect and more money than the recording artist, and that was like the

owner of the label or the music mogul executive. And so I was like, I wanted

to do that.

And so that's what I chose. A lot of people chose at first to become a

recording artist. I chose at first, I was like if I could become that guy

that's there that the music artist is asking the questions of, then, you know,

my chances to finally one day be on the stage, I think my chances would be

better going that route first.

GROSS: How does being on stage on Broadway compare to being on stage in front

of a very enthusiastic hip-hop audience?

Mr. COMBS: Yeah, it's just totally different. It's just, you know, acting,

and, you know, being a musical artist, there are some similarities, but to be

honest here, like, they're totally different, you know, and the two stages are

totally different. You know, at one place, even though there are times as

musical artists we try to bring, you know, a live theater feel to our

concerts, it's nothing like, you know, performing on stage, on Broadway for,

you know, two and a half, three hours, and you can almost hear a pin drop, and

the audience, you can hear every breath that they take.

And you know, you know, performing in front of like, you know, in Wembley

Stadium, because I just don't perform just in front of hip-hop audiences. I

also perform like in front of, whether it's a rock audience or when I did the

Princess Diana concert at Wembley Stadium, that's like, you know, 60,000

people. It's another level of just impromptu type of freedom and, you know,

connection with the crowd, of really trying to get them engaged. The whole

time, you're like trying to like pull them in closer and closer and closer to

you so you have this eruption. And so in a sense, it is the same thing, but

it's just different. So I don't think I answered that question the best way,

but it's the best way to answer the question. You understand?

GROSS: Sean Combs will be back in the second half of the show. He starred in

the recent ABC movie adaptation of "A Raisin in the Sun," which is now out on

DVD. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: When you're on stage on Broadway you're in character, you're playing

somebody else. When you're on stage in concert, do you feel like you're

playing somebody else there, too, or do you feel like you're yourself on

stage?

Mr. COMBS: You know, I mean, me I'm more of myself. I'm not playing like a

total different person, yeah. I mean, a lot of me is on the stage, you know.

But there's like maybe 20 percent that is like just a character that you turn

off, you know, when you get off the stage. But a lot of what makes you

special if you're a great performer on the musical stage is if you are able to

bring yourself to that, and it's something about yourself that is different

than all other performers.

GROSS: You know, you have all these different names that you've used for

different things. You know, you're Sean Combs, you're Puff Daddy, you've been

P. Diddy. And so I'm wondering if like Puff Daddy or P. Diddy has like a

different personality than Sean Combs?

Mr. COMBS: Mm-hmm Yeah.

GROSS: If you see it as like a character in a way?

Mr. COMBS: Yeah, it does. They are. I think we as human beings, we have

different sides to ourselves. And I just named all those different sides. It

wasn't, you know, that I was--and it was something that--with the name thing,

it was just like, it's just having fun. A lot of people ask the question.

It's not a serious thing, like so I answer to any of my five names so as not

to confuse you. But, yeah, it's definitely different sides of my personality.

GROSS: Now, your first hit under your own name was about your friend Biggie

Smalls who was gunned down a few feet away from you in 1997. It was a kind of

goodbye to him. You were so close. I don't want to get too personal here,

but what impact did his murder have on your life, the reality of violence in

your world like that, somebody you were so close to being shot in front of

you?

Mr. COMBS: Yeah. You know, I lost my father that way, and then, you know,

losing him, you know, one of my best friends. And then after that I lost two

more of my best friends, all to the same way. They were all shot and killed.

It's a tragedy that, to be honest, it's just something that, you know, growing

up in the inner city it's almost like you're prepared for it. It's almost

strange when you have a friend who's a black male die of like cancer or

something. It's almost normal when you hear, when you get the call or you

witness somebody, a friend of yours gets shot and killed. And it was just as

devastating, no matter what it is, to lose somebody that you love. But, you

know, the tragedy is that it's almost like a lot of us depends on where we

grow up, it's like we're prepared for things like that. And that's something

that I feel has to change in this world.

GROSS: You know, some people say rap glorifies violence, or glorified

violence back in the '80s and '90s, you know, particularly, and that rap made

violence seem like the authentic way of being African-American. And other

people say, no, rap just reflected the violence that was out there. What do

you think?

Mr. COMBS: Yeah, I mean, I feel it was a reflection and also I feel like at

points it definitely was glorified, but it was a true reflection. But, you

know, then it was like, because you couldn't get away from it, OK, well if I'm

in the situation at least I'm going to be the baddest that was ever in this

situation. And then there have been times in the music it has been glorified.

GROSS: Well, I'd like to play the first hit that you had under your name, and

it was an homage to Biggie Smalls and about how much you missed him. It's

called "I'll Be Missing You." And I'm not sure if it's a sample or just like

musicians playing the riff from it.

Mr. COMBS: Yeah, it's a sample.

GROSS: It's a sample? OK.

Mr. COMBS: It's a sample of Sting.

GROSS: From the Police "Every Breathe You Take."

Mr. COMBS: Yes.

GROSS: So let's hear it. This is my guest Sean Combs, and you recorded this

under Puff Daddy, right?

Mr. COMBS: Yeah.

GROSS: OK, here it is.

(Soundbite of "I'll Be Missing You")

Mr. COMBS: This right here--tell me why--goes out to everyone that has lost

someone that they truly love. Come on. Check it out.

(Rapping) Seems like yesterday we used to rock the show

I laced the track, you locked the flow

So far from hangin' on the block for dough

Notorious, they got to know that

Life ain't always what it seemed to be

Words can't express what you mean to me

Even though you're gone, we still a team

Through your family I'll fulfill your dreams

In the future, can't wait to see

If you open up the gates for me

Reminisce some time, the night they took my friend

Try to black it out, but it plays again

When it's real, feelings hard to conceal

Can't imagine all the pain I feel

Give anything to hear half your breath

I know you still living your life, after death

Unidentified Woman: (Singing) Every step I take, every move I make

Every single day, every time I pray

I'll be missing you

Thinkin' of the days...

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: My guest is Sean Combs, Puff Daddy. And that was his first hit, a

shout out to his late friend Biggie Smalls.

So, you know, in addition to music and acting, you also have your fashion

company, Sean John, and your label. And, now, I read that your grandmother

was a seamstress. Is that right?

Mr. COMBS: Yes. Yeah, yeah. My grandmother, she was the neighborhood

seamstress. And so when I was growing up I didn't realize that that's one of

the ways I was going to get kind of my preparation to become a designer. But,

you know, I used to, you know, assist her in the house, you know, cut the

patterns and, you know, help, you know, press things and get things to be

ready to be delivered. And, you know, it gave me a sense of understanding

detail and fit on a garment. And I didn't realize that at that time that, you

know, it would come to some use as I got older.

GROSS: You know, it's interesting, I think, you know, like, you know, some

boys and young teenagers would think of that as being too feminine, you know,

anything associated with sewing.

Mr. COMBS: Yeah. Mm-hmm.

GROSS: But obviously that didn't bother you?

Mr. COMBS: Yeah, no, it didn't bother me. I've always be comfortable in who

I was, you know. And, no, it was cool with me. My mother, she was making me

take guitar lessons and she tried to get me in some ballet classes and tap

dance. So I had to get over the whole worrying about if something was

feminine early. You know, with my mother, she wanted to make sure I was well

rounded. So I got I passed that early.

GROSS: Did you take tap or ballet?

Mr. COMBS: Yeah, I took tap and ballet for like two days.

GROSS: But you ended up being a dancer.

Mr. COMBS: Yes. Yeah, I ended up doing tap dancing. But the ballet was

just a little too hard for me. I'm not really that flexible neither.

GROSS: So with your grandmother, did you actually learn things that you can

use as a designer now, or is, you know...

Mr. COMBS: Yes, yes, definitely. She taught me about fit and she taught me

about attention to detail. Just being there with her, you know, the way she

was a perfectionist about making sure every garment was perfect.

GROSS: Did she make clothes for you?

Mr. COMBS: Yes, she makes all my--all my clothes on Easter Sunday was made

by my grandmother.

GROSS: Now, the great thing about having a relative make clothes for you is

that you're going to have something that's unique. The not so great thing is

if you want to look like everybody else, you won't.

Mr. COMBS: Yeah.

GROSS: You know, if you want to buy like whatever the popular brand is, isn't

your grandmother's brand.

Mr. COMBS: Yeah, but, I mean, I think that separates the leaders from the

followers. And I always wanted to be a trendsetter, so I always wanted to

wear something that nobody could get. I always wanted a one of a kind piece

from when I was like six years old, so.

GROSS: Can you describe one of the greatest things she made you?

Mr. COMBS: Yeah, she had made me--it was like a navy blue suit with gold

buttons. It was a three piece suit. And, you know, back in those days, like

the gold buttons used to have the accents. And so, yeah, I remember that.

That was for Easter. That was on Easter Sunday.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is Sean Combs, also known as Puff Daddy, P. Diddy, a hip-hop

performer, producer, fashion designer, actor, and you've got your own

fragrance also. And he starred in the Broadway production of "Raisin in the

Sun," the revival from a couple of years ago. And that was adapted with the

same cast into an ABC movie that's just been released on DVD.

The first movie that you made was called "Made." And it was directed by Jon

Favreau, starred Favreau and Vince Vaughn. And they're two guys who get sent

from the West Coast to New York to do a kind of a crime deal that they don't

really quite understand, and you're their contact in New York. And I want to

play a scene from this film.

Mr. COMBS: OK.

GROSS: You're in a restaurant on the phone making business deals when they

walk in.

(Soundbite from "Made")

Mr. COMBS: (As Ruiz) No, man no. It's too risky. I want out. Listen, man,

we made a lot of money on this one together, but it's over. (Word censored by

network)...going down. I'm selling my--this Internet...(word censored by

network)...is entirely too volatile. I'm going to take my block of Microsoft.

Yeah. OK, what problems they're having and then they get Bill Gates is a

bad...(word censored by network). Yeah, and I'm going to take my profits on

Yahoo! and all the portal stocks. Yeah, the bubble's going to pop. All

right then. Peace.

(Soundbite of phone being turned off, put down)

Mr. COMBS: (As Ruiz) That's it. This is Max's calvary?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COMBS: (As Ruiz) And who the...(word censored by network)...swelled you

all up like that?

Mr. JON FAVREAU: (As Bobby Ricigliano) No one swelled. We had a thing with

each other.

Mr. VINCE VAUGHN: (As Ricky Slade) Oh, yeah. Tell him. He asked me a

question, I said shut...(word censored by network)...up.

Thank you, man. It's good to meet you.

Mr. COMBS: (As Ruiz) If this...(word censored by network)...don't all. Max,

he done send me two broke...(word censored by network)...swelled up guineas

from LA. I could have hired some local guineas for some beer money. Ain't

that right, Leo?

Mr. LEONARDO CIMINO: (As Leo) Sure. You boys want anything?

Mr. FAVREAU: (As Bobby Ricigliano) Yeah, bring us four...(unintelligible).

Mr. CIMINO: (As Leo) Four...(unintelligible).

Mr. VAUGHN: (As Ricky Slade) Oh, no thank you. Actually I'll have a Strega,

please.

Mr. COMBS: (As Ruiz) What...(word censored by network)? You're drinking the

witch after dinner? No class.

Mr. VAUGHN: (As Ricky Slade) Look, there's absolutely no reason to start

name calling.

Mr. COMBS: (In character) It's midnight and this...(word censored by

network)...is ordering an apertif.

Mr. VAUGH: (As Ricky Slade) Actually, with all respect, Ruiz, it--a Strega

is a digestif.

Mr. CIMINO: (As Leo) A Strega is an apertif.

Mr. COMBS: (As Ruiz) Sorry, Leo. I'm going to get up out of here, man.

What do I owe you?

Mr. CIMINO: (As Leo) It's on the house.

Mr. COMBS: (As Ruiz) Thanks a lot. Love you, man. If you need anything,

you give me a call.

Mr. CIMINO: (As Leo) Thanks.

Mr. COMBS: (As Ruiz) All right.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That was Sean Combs with Jon Favreau and Vince Vaughn from Sean Combs'

first movie "Made."

What did you learn that you had no idea about from your first movie

experience?

Mr. COMBS: My whole concept with my film career has been to surround myself

with great, talented people, to work with great, talented people. To learn

from them and to be able to work with these guys is one of the, you know,

exciting ways to start your film career because on the set with, you know, Jon

Favreau and Vince Vaughn, it's very improvisational. It's a lot of fun. It's

very free, freeing yourself up and very rebellious. And just being able to

work with them and just learn that side of things, and also comedic timing. I

was able to learn a lot by working with them.

GROSS: In the scene that we just heard, you're very well dressed. You have

on these great sunglasses, a diamond earring, a fine suit. Did you choose all

that yourself?

Mr. COMBS: Yes. You know, I just wanted--I didn't want to do the do the

stereotypical just the way you saw, you know, the stereotypical, you know,

street guy. And so I wanted to, you know, to give him a little bit more

sophistication and versatility. And they let me do that.

GROSS: It kind of gave him more power, too, I think.

Mr. COMBS: Yeah. Yeah, you know, I mean, he--inside he really is a

businessman and wants to be a businessman. And so sometimes he puts on his

Wall Street suit on so he could really play the role all the way out. And

that's the way I saw the character.

GROSS: Now, another film that came out the same year as "Made" did, 2001, is

called "Monster's Ball." And you played someone who's on death row. And Halle

Berry is your wife. I want to play a scene in which your young son comes to

visit you in prison. It's going to be his last visit with you before you're

executed, and here's the scene.

(Soundbite from "Monster's Ball")

Mr. COMBS: (As Lawrence Musgrove) We ain't got a lot of time. I want to

give you all my drawings, and all my clothes. When you get older they may fit

you and you may want to wear them.

Mr. CORONJI CALHOUN: (As Tyrell Musgrove) I'm not going to see you again

after this?

Mr. COMBS: (As Lawrence Musgrove) No.

Mr. CALHOUN: (As Tyrell Musgrove) Why?

Mr. COMBS: (As Lawrence Musgrove) Because I'm a bad man.

Mr. CALHOUN: (As Tyrell Musgrove) Who says?

Mr. COMBS: (As Lawrence Musgrove) I do. But I want you to know something.

Mr. CALHOUN: (As Tyrell Musgrove) What?

Mr. COMBS: (As Lawrence Musgrove) You ain't me.

Mr. CALHOUN: (As Tyrell Musgrove) Yes, I am.

Mr. COMBS: (As Lawrence Musgrove) No, you're not. You're everything that's

good about me. You're the best of what I am. That's what you are.

(Soundbite of footsteps)

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's Sean Combs in a scene from "Monster's Ball" from 2001.

What did you do to prepare for this film, to get in a mind of somebody on

death row?

Mr. COMBS: Oh, I actually went and I did some research. I went into Angola

State Prison and I went to death row and I spoke to some inmates there on

death row. And, you know, any time, you know, I'm blessed to get a role I do

intensive research and preparations. And so I actually went down there and

really sat in a cell for a couple of hours, tried to understand the solitary

environment that they're in, you know. And actually being able to talk to the

inmates, it gave me a lot of insight on just the world and that the bottom,

how low of a point you're at in your life to be there and how--but how you're

trying to hold it all together but, you know, you're just a second away from

breaking. And, you know, it was definitely something that was sad, really,

you know, getting the information and doing the preparations.

And the scenes were very, you know, the only way I could--they were very sad

scenes, you know. Even when I look back at them, you know, to just be able to

have to sit there and talk to your son before you know you're going to die.

And you know that you've, you know, made a grave mistake.

GROSS: You're actually shown being electrocuted...

Mr. COMBS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...in the film and, you know, you're strapped to the electric chair

and your body, you know, convulses...

Mr. COMBS: Yes.

GROSS: ...as you're electrocuted. Tell me about shooting that scene.

Mr. COMBS: Shooting that scene was extremely eerie because everything was

real. So the chair that I was in and the things that were on my head and

everything that was where what they actually use in the way, you know, the

things they actually use to electrocute people and to kill them. And so none

of it was props. And so you could actually, in a sense, you know, it felt

kind of eerie. You could feel almost like the spirits there. And, you know,

I just used it. Instead of getting scared, I just used it to channel the

situation and make it realistic. And a lot of people say that that was my

best scene. So I said I could always--at least we know that I could get

electrocuted the right way. I had to tell people that wasn't a stuntman or a

double, that was actually me.

But, you know, yeah, it was that realistic, though, that people asked was

that, you know, was there some sort of trickery with that. No, that was

really just me really acting out the way I felt it would feel. You know, I

mean, and even just have the director yell `cut' and to take the mask off and

see everybody's faces and see them looking at me and see like they like, you

know, the feelings they were going through was really--it was really real, you

know.

GROSS: Well, just one last question. How much sleep do you get a night?

Mr. COMBS: I'm going to say like five hours, four hours.

GROSS: Can you run on that? I mean, do you have insomnia or are you just too

busy to sleep?

Mr. COMBS: Yeah, no, I have insomnia. And, you know...

GROSS: And so when you can't sleep you put that to use?

Mr. COMBS: No, I don't have insomnia.

GROSS: You don't have insomnia? OK.

Mr. COMBS: No, I do, but you got to watch what you say. So I don't have

insomnia. I don't want to put that out there. I'm going to change that up.

I don't have it anymore. I just got cured today.

GROSS: Hey, congratulations.

Mr. COMBS: Thank you, thank you. Thank you very much. I don't have

insomnia anymore. Tonight I'm going to sleep great.

GROSS: Good luck. Thanks so much for talking with us.

Mr. COMBS: Thank you. Thank you very much.

GROSS: Sean Combs starred in the recent ABC movie adaptation of "A Raisin in

the Sun," which is now out on DVD.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: John Powers on the documentary "Operation Filmmaker"

TERRY GROSS, host:

The war in Iraq has inspired a unprecedented number of movies of all kinds, in

particular documentaries about everything from torture in Abu Ghraib to heavy

metal fans in Baghdad. A new documentary by Nina Davenport called "Operation

Filmmaker" approaches the war from a vantage point largely outside Iraq. It's

the story of a young Iraqi who leaves his country in hopes of becoming a

filmmaker. Our critic at large John Powers has a review.

Mr. JOHN POWERS: If there's one clear cultural lesson to be drawn from the

war in Iraq, it's that people don't go to movies about an ongoing war that

isn't going particularly well. So I feel slightly perverse in telling you

that there's a new film about Iraq that you might really enjoy. It's a

documentary called "Operation Filmmaker" by Nina Davenport. And the first

thing you should know about it is that it's not grim or hectoring. It is, in

fact, a comedy that would have been appreciated by Billy Wilder or Luis

Bunuel. It shows what happens when the very best of intentions bump into the

untidy reality of living human beings.

The story begins in 2004 when the actor Liev Schreiber sees an MTV item about

a Baghdad film student named Muthana Mohmed who's burning to make movies.

Schreiber's about to direct his own first film, "Everything Is Illuminated,"

and in a burst of generosity decides to invite the 25-year-old Shiite to the

Czech Republic to work on the production. In what proves a burst of canny

intuition, he also invites Davenport to make a film about the young Iraqi's

experience on the set.

At first everything is great. Schreiber goes to the Prague airport to pick up

Muthana, who's obviously delighted to be there. But almost instantly the rose

loses its bloom. Even as Muthana feels insulted by what he's asked to

do--he's instructed how to properly stir the trail mix for one of the film's

vegan producers--Schreiber and company feel let down by their protege. Rather

than behaving like an ambitious young American filmmaker who'd do anything to

ingratiate himself with the bosses, Muthana strikes them as, well, difficult,

by turns prickly and mocking, he blows off assignments, bubbles with

resentment and makes people feel guilty. To top it all off he doesn't even

agree with them politically. Here producer Peter Saraf talks to Muthana about

the strange politics of their situation.

(Soundbite from "Operation Filmmaker")

Mr. PETER SARAF: When Liev and I first started talking about the idea, we

saw you on MTV, and, you know, we talked about such sort of high concept

things like, well, this idea that we're making this movie about young people

connecting over a cultural divide. And like the experience of these two

American Jewish guys who are here to make a movie with an Iraqi man, there's a

cultural divide that we have to cross. And here I am this like, you know,

left wing American in terms of my politics and all this stuff. And, you know,

and so I had to confront this idea that like you weren't opposed to the war.

So anyway, so then--and this is coming out in Entertainment Weekly

tomorrow--so that I say--I'm quoted as saying, you know, we had this idea,

blah, blah, blah, but I never imagined that Muthana would ever say to me, `I

love George Bush, he changed my life.'

Mr. MUTHANA MOHMED: I love George Bush.

Mr. SARAF: Mm.

Mr. MOHMED: You're disappointed?

Mr. SARAF: No, no, not at all. I'm not disappointed, you know. You're, you

know.

(End of soundbite)

POWERS: In fact, everyone is disappointed. And as the story progresses, you

start to realize that "Operation Filmmaker" isn't just a movie about a young

Iraqi filmmaker. It's a sly parallel about Operation Iraqi Freedom and how

the occupation went wrong. What makes this portrait of star-spangled naivete

all the slyer is that it centers not on neoconservatives who championed the

war, but on show biz progressives who opposed it.

Good liberals, Schreiber and Saraf clearly have a fantasy of saving the young

Iraqi and putting him on the way to a life like their own. But just like Iraq

itself, Muthana has his own dreams, limitations and history. Even as he

expects too much too soon, he clearly wants to be handed overnight success and

prosperity. He knows that if he returns to Baghdad he may well be murdered.

And so while Muthana keeps hustling for dear life, his rescuers clearly can't

wait to get him off their hands.

The one with no exit strategy turns out to be Davenport, who was supposed to

merely be documenting Muthana's experience but winds up being sucked into it.

Eventually the two get caught in a cycle of mutual exploitation. Without

Muthana's cooperating, Davenport won't have enough footage to complete the

film. She'll have wasted many months and lots of money. Of course, he knows

that, and so he begins demanding her assistance, some of it financial, to keep

letting her film his life.

While their Apache dance is itself a metaphor for the occupation, it also

offers a valuable corrective to our ideas of nonfiction film making. Most

socially conscious documentaries encourage us to think two slightly

contradictory things: first, that we're watching unadorned life through the

eye of an impartial observer; and second, that this impartial observer is

implicitly a hero because he or she self-effacingly cares enough to show us

the life of the poor, the unhappy, the struggling and the lost. Davenport's

movie puts the lie to all that. As she dickers with Muthana to keep him

onboard the project, the project being a record of his own precarious life,

we're reminded that every documentary comes larded with agendas and

negotiations. In its amusing way, "Operation Filmmaker" demonstrates that the

idea of a clean, heroic, objective documentary is as much a fantasy as the

notion of saving a country with a quick, easy invasion. In the real world,

even the most benevolent-seeming relationship can easily become a quagmire.

GROSS: John Powers is film critic for Vogue. He reviewed "Operation

Filmmaker."

You can download podcasts of our show on our Web site, freshair.npr.org.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.