As Marriage Standards Change, A Therapist Recommends 'Rethinking Infidelity'

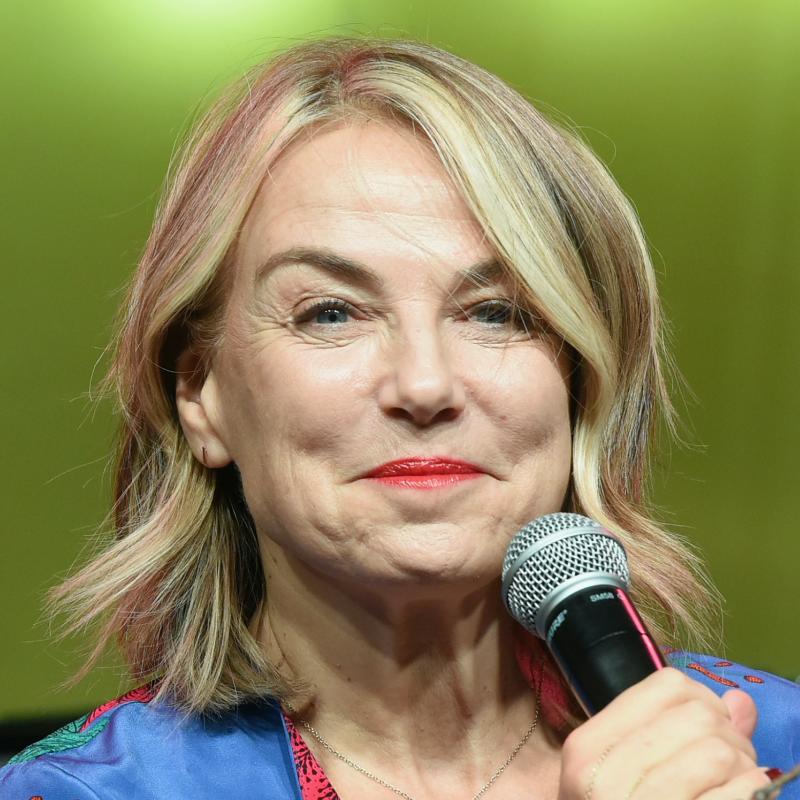

Why do people cheat? And what is the definition of infidelity? Psychotherapist Esther Perel is the author of the new book The State of Affairs. She works with couples who are dealing with infidelity and says infidelity is "extremely common" but is "poorly understood."

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on December 13, 2017

Transcript

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. My guest, Esther Perel, writes in her new book "The State Of Affairs" (reading) there is one simple act of transgression that can rob a couple of their relationship, their happiness, their very identity - an affair. Yet this extremely common act is poorly understood. She adds, (reading) these are confounding times for couples. Eroticism is not always politically correct.

Perel has spent the past six years of her long career as a psychotherapist focusing on couples who are dealing with infidelity. She's heard a lot of stories. And those stories have connected with a huge audience. A TED Talk she gave in 2015 called "Rethinking Infidelity" has over 8 million views. An earlier talk from 2013 called "The Secret To Desire In A Long-Term Relationship" has over 11 million. She also hosts a podcast called Where Should We Begin? that features real couples who volunteer to be recorded in intense therapy sessions. Perel is the daughter of Holocaust survivors. Earlier in her career, she worked with families in cultural transition - refugees, immigrants and intercultural, interracial and interreligious couples.

Esther Perel, welcome to FRESH AIR. So do you think we have unrealistic expectations of marriage?

ESTHER PEREL: We definitely have higher expectations of marriage today than we have ever had. Relationship expectations are at an all-time high. We want everything that we expected in traditional marriage in terms of companionship and economic support and family life and social status. And then we also want what a romantic marriage brought us, which was a sense of belonging and connection and intimacy and a best friend and a trusted confidant and a passionate lover. And then we now also want self-fulfillment and - in our relationships. And we want to find a soulmate, a word that for most of history was reserved to God.

GROSS: And somebody who stays sexy for us forever.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: So...

PEREL: And forever keeps on getting longer.

GROSS: Well, in your book about affairs you ask a question that I think people assume has an obvious answer, but maybe it doesn't. And the question is, what is an affair? Because it's kind of a blurry line. Like, as you say - like, is phone sex an affair? If one of the people sees a prostitute, is that an affair? Talk about that blurry line.

PEREL: The definition of infidelity keeps on expanding. And there is no universally agreed-upon definition of infidelity. It is often deeply culturally connected. And the lines keep on expanding. So if in the past you could say that the result of an infidelity was a child, and the child would come out nine months later and the color of the hair of that child would not resemble yours, and therefore you had a clear marker, things today are a lot more diffuse.

And so when you ask, you know, is it a love affair, is it watching porn or is it only watching porn if the other person is live on the other side, is it staying secretly active on your dating apps - when we say is it, today the definition is often subjective and in the hands or in the mind of the two people that are part of one relationship. There is no hierarchical structure from above that tells you this is considered a transgression. And therefore, these conversations need to take place quite early on in ways that they never had before. Monogamy can no longer just be assumed. It needs to be negotiated and defined.

GROSS: Oh, and you ask, like, is it still cheating when your spouse no longer knows your name because they have Alzheimer's? And you had a patient who was in that situation.

PEREL: Yes. This theme of my partner is ill, my partner is bedridden, my partner has MS, I am taking care of my partner. And my - this is a person who does recognize my name. But I take care of my partner. I am loyal. I am not faithful. I will be there till the last day to take care of my partner, who I love deeply. And in the last few years, I have had a companion, a lover.

There - this is a much - it's a different state of affairs that is not titillating, that is not about narcissism, that is not about cheating, that is about longing and yearning and a desire for connection and for intimacy, all the while staying deeply involved in the relationship. So what it says is that the world of affairs is deeply complex, multilayered, and can't so simply be reduced to black and white.

GROSS: How often do you end up seeing couples because one of the members of the couple found the other person's phone or iPad and they've seen texts or emails or photos that gives away the fact that they're having an affair?

PEREL: It's never been easier to cheat, and it's never been more difficult to keep a secret. The majority of affairs would normally have died a natural death. Today they are discovered primarily through the phone or through social media or through the computer. So I would say that when people come to me or to a therapist in the immediate aftermath of the revelation of an affair, it is often because it's been discovered through the phone or somebody basically sent you a message on Facebook or things like that.

And then you don't just discover one message. That's the big shift here, is that you get to enter the digital archive and you scavenge it for hours. And you see every hundreds and thousands of texts and pictures. And that is a death by a thousand cuts. That is a form of gutting that we didn't have before. You could imagine it. Now you're reading it. You're seeing it. And your entire reality gets shattered. And you can't leave it. So many people will come to see a therapist right after an affair is revealed or discovered or exposed.

GROSS: So you say sometimes when we seek the gaze of another it isn't our partner we're turning away from, but the person we've become. We're looking for another version of ourselves. Can you expand on that for us?

PEREL: When you pick a partner, you pick a story. And that story becomes the life you live and the parts of you that become expressed. And sometimes you realize after years of living those parts of you that there are other parts of you that have virtually disappeared. The woman disappeared behind a mother. The man disappeared behind a caregiver. The sensual person disappeared behind a responsible person. And there is an expression of longing and yearning - longing for connection, for intensity, for a sense of aliveness (ph), which is really the word that many people all over the world would tell me when they are having an affair.

They don't talk about sex and excitement and titillation actually. They - I'm talking affairs now. I'm not talking about just extramarital sex and the myriad of ways to do that. And what they say is they feel alive as in vibrant, vital, as in a reclaiming of something that had gotten lost, a lost part of themselves or a lost sense of youth or a lost sense of possibility. And that often when there is affairs, people - those kinds of affairs - what people talk about is a reclaiming of the lost parts of themselves. And so they're not necessarily wanting to reject their partner. They don't want to reject their life. They love that partner and that life. What they want is to reconnect with a different part inside of them.

And those are a certain kind of affairs. They're not - certainly not representative of the vast array of them. But they are very significant because they are often done by people who have been faithful for decades. These are not repeat offenders, philanderers, chronic strayers. Those are people that are very committed. They're not cheaters. They're a little more than that.

GROSS: You know, something else you write is that we assume that the faithful partner is the mature, committed, realistic partner and the one who strays is selfish, immature and lacks control. What's wrong with that assumption?

PEREL: You have a way of asking the question (laughter). I think that if we decide that the - how would we say this? Relationships are complex. And there are many ways that people let each other down, that people do not show up for each other, that people break their vows. In other words, betrayal comes in many forms. And sometimes just because one has not cheated or slept with somebody else doesn't inherently give that person moral superiority. Sometimes a partner has been deeply absent, neglectful, indifferent, contemptuous, rejecting sexually for nine years in a row.

And we sometimes put the betrayal of an affair as the ultimate betrayal, as the hegemony of all betrayals when, in fact, in the relationship, there may be other ways that people have fallen short for each other. And maturity is not just measured by sexual exclusivity. Maturity is measured by a lot of ways that people act, respond, show up, breed trust, are reliable, are predictable, are loving, caring, care and tender in a relationship.

GROSS: As a couple's therapist, when you're dealing, say, with a couple where one partner wants fairly frequent sex and the other partner doesn't really enjoy sex and doesn't want it frequently and, therefore, they've become sexually incompatible - what's your position for the partner who desires something that that partner can no longer get within the marriage?

PEREL: I think that if you just ask a question about what to do with the discrepancy around desire for sex in a relationship and you look at it just as if it's that what people miss is the act of sex, you sometimes fail to understand what it is that people are really asking for. You know, what - sexuality is often a pathway for connection, for intimacy, for tenderness, for sensuality, for playfulness, for power, for curiosity, for relaxation. And when people are deprived of sex, it's this whole sense - set of feelings and experiences that they are deprived of, not just the act.

They can have sex in various places. What they want is everything that the connection gives them. When they are deprived of that, what they often experience is a depletion of energy, of vibrancy, of aliveness, of vitality. That's what they're yearning for. When people complain about the listlessness or the lack of their sex life, they sometimes may want more, but what they want is better. And the better is the quality of renewal, of connection, of playfulness that sex affords them.

So the first thing in the session is to make clear that this is - the conversation is not about sex, the conversation is about loss. And it is loss on both sides. The person who is no longer interested sometimes is not so happy about that either. You know, so I wouldn't assume that it's just a comfortable, easygoing stance on that side. There are two people who are experiencing a sense of loss in their relationship, which they are both experiencing.

It isn't one person is holding power over another only. Because unless there is rape in a relationship, it is the person who wants less who has the control, who has the power that you can't force. Otherwise, you enter into a different dynamic. So you are...

GROSS: Wait, wait. I'm going to stop you. That's an unusual way of looking at it - that it's the person who wants less who has the power.

PEREL: Unless there is coercion, yes. Yes, if I don't want to coerce, I am at the mercy, I am dependent on your willingness. Maybe not even your interest, but your willingness. Yes, that is - I can go hike by myself, if you are not there to go on a hike with me. I can do a lot of things by myself that you may not be interested in. But this one is a shared experience. And if you do not want to share it with me, unless I impose it on you, you make the decision.

GROSS: So in a situation like that, do you say...

PEREL: Man or woman, by the way. This is not a male prerogative. So we should not fall into the stereotype of thinking that this is - a man is interested and a woman is not. And this can happen in same-sex couples, too.

GROSS: Let's take a short break. And then we'll talk some more. If you're just joining us, my guest is Esther Perel. And her first name is spelt like Esther, but pronounced Estaire. She is the author of the new book "The State Of Affairs: Rethinking Infidelity." She's a psychotherapist who has practiced for about 30 years and - with couples - couples therapy, but for the past few years has focused on infidelity. We'll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is Esther Perel. She's a psychotherapist who has worked with couples for about 30 years. And for the past few years, she's focused on infidelity. Her new book is called the "State Of Affairs: Rethinking Infidelity."

When someone no longer feels sexually aroused by their partner, is that something that you feel they can get back again - that feel - feeling of arousal?

PEREL: So arousal is one thing. Desire is something else, and willingness is a third.

GROSS: OK.

PEREL: We do not start sexually only because we are aroused and turned on. We sometimes start to be involved sexually because we have willingness. You're not always hungry, but then there is food in front of you. And it smells really good. And it looks beautiful. And you taste, and then you realize, after all, I wouldn't like - wouldn't mind a little bit more and then you eat. And then, even after you ate, you may say that was delicious; I wasn't really hungry. And you still enjoyed it.

So we have multiple doors for entering into an intimate engagement with our partner. And excitement is just one of them. Sometimes you are desirous, but you don't have an arousal. You're not turned on physiologically yet, but you have the idea. You have the wish for it. You're in the mood. And sometimes you are excited and turned on, but you're not necessarily in a state of desire.

I think we need to separate these concepts and these entry points, first of all. Second of all, I think the more important question sometimes when it comes to desire isn't - put it this way, a question I ask a lot is, I turned myself off how? I shut myself down - I shut down my desires how? And that's not the same as, you turn me off when and what turns me off is. That puts the responsibility only on the other person as if, you know, the other person did some amazing things, it would move me.

The fact is that if I am shut down, if I have closed the door, you can do a lot of things. There will be nobody at the reception desk. There needs to be a receptivity, an openness, a willingness. And that is the fundamental sovereignty of desire. That is something that I own. I decide if I want to open that or not. So when you ask people - you know, I shut myself off or I turn myself down, you know, what they're talking about is the ways in which they have closed themselves off to the possibility of touch, of connection, of sensuality, of pleasure, of surrender, you know, for a host of reasons that range from sexual trauma to self-criticism to lack of self-worth to negative body image to issues of self-esteem. It is those things that make us close ourselves down.

GROSS: Is that something...

PEREL: And...

GROSS: ...You can help fix, though, to help create communication of intimacy and sexual fulfillment when it isn't there?

PEREL: Yes, many times. That's the work. Yes (laughter). The work is about helping people often to reconnect with parts of themselves that they have neglected or that they have - they are in conflict with, or that they despise, or that they feel loathsome about, or that they don't feel deserving of because they gained too much weight, because they don't feel like they've done enough - they have performed well enough at work, because their mother left them for another man.

And so they decided that they would remain - they would be all mother, and they killed the woman inside of them the day they had a child. Or because their father was violent and aggressive and they don't know how to bring together love and lust. Those are the deeper conflicts around desire and around intimacy and sexuality that I work with in my practice. This is a major part of the work - not everybody and not everybody with the partner that they are with, of course. But these are not irreversible, immutable stains. These are deeply conflicted experiences of life. And we work with that.

GROSS: You sometimes tell couples where one of them is having an affair, like, your marriage is over. Do you want to start a new one? What do you mean when you ask, do you want to start a new marriage together?

PEREL: It came from an idea that I had at some point that most of the people in the West at this moment or many people in the West at this moment are going to have two or three marriages in their lifetime. And some of us are going to do it with the same person. Sometimes the crisis of an affair is the end of a marriage, the one that people knew for 10, 15, 25 years. And then the question is, do you want another one together? Do you want to create a different relationship with each other? Do you have enough between the two of you in terms of life, capital, history, shared values, love, care, attention, family that says, I don't want to leave this?

I still, you know, regardless of - you know, you hurt me badly and I still love you. Or I hurt you badly and I still love you. And from that place, we're not going backwards. We're not going back to the marriage that you had. That's a given. And that means that the crisis of an affair often will light up the score card in a relationship. The compromises people made for the greater good, the arrangements, the roles they took on, the power structures that they accepted, the financial arrangements that - now that's it. You can all renegotiate the entire thing.

And it gives hope. It gives possibility. It says to people, this is a big crisis, but people can repair and re-pair. And people will develop resiliency out of this. And there will be post-traumatic stress. And there may be post-traumatic growth. Not for everybody. Many affairs will break a relationship. Sometimes it was already dying on the vine. And many affairs will remake a relationship.

GROSS: My guest is psychotherapist Esther Perel. Her new book is called "The State Of Affairs: Rethinking Infidelity." We'll talk more after a break. And we'll listen back to an interview with Pat DiNizio, who was the lead singer and guitarist of The Smithereens. He died yesterday at the age of 62. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF DICK JOHNSON QUARTET'S "THE END OF A LOVE AFFAIR")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross back with psychotherapist Esther Perel. Her new book, "The State Of Affairs: Rethinking Infidelity," draws on her work with couples who are dealing with infidelity. Earlier in her career, she worked with families in cultural transition - refugees, immigrants and intercultural, interracial and interreligious couples.

So you were born in Antwerp, Belgium. Your parents were Holocaust survivors. Were they in the same camp together?

PEREL: So I'm born in Leuven, actually, not in Antwerp.

GROSS: Oh, OK.

PEREL: No, my parents were - my father was in 14 different labor camps, my mother nine. They met on the day of liberation on the road...

GROSS: Wow.

PEREL: ...In Poland.

GROSS: And you've written that they were both the sole survivors in their families. Do you know, like - did meeting each other just after they were liberated from the camps and being the sole survivors in their families - was that a bond? I mean, what a unique bond that is. Was that a bond that strengthened their marriage even though it - you know, it's the most horrible imaginable thing to have happened? But - yeah.

PEREL: So I actually have written quite a bit about marriages of the Holocaust. And here is the thing. I'm alone. You're alone. I have nothing. You have nothing. I've lost everyone. You've lost everyone. Let's get married. That was indeed a bond that made many people marry. But for many of them - and they would - those are marriages that would not have happened if - prewar. These were not people that would have probably been put together. But for many of these couples, this bond was there for the initial phase of survival and revival. It wasn't necessarily enough for a good relationship. That still took something else.

So there were many couples after the war who, after they did the rebuilding, the reconnecting with life, the rehumanization process, did look at each other and say, what do you and I have in common? We have nothing in common. We come from completely different worlds. And so you could see the couples who did have more than that, and they would never have met, and it was a luck that they had met because they actually created something very beautiful together, which I think my parents were part of that. But I think there were many other relationships where the bond was not necessarily the only thing necessary for a thriving relationship.

GROSS: Did you grow up among a lot of adults who were Holocaust survivors, in addition to your parents?

PEREL: Only. I grew up in a community that was all Holocaust survivors in Antwerp. The majority were people who came after the war from the camps from Eastern Europe. And a few were Belgians who had been hidden during the war in the countryside and came back to the cities. Sixty thousand Belgian Jews were deported to the camps, so there were very few original Belgian Jews left. The entire community came directly from the camps to Belgium.

GROSS: What image of the world did it give you, growing up with Holocaust survivors?

PEREL: I think that when you've lived - you know, it is an experience that you get through osmosis. It just enters with mother's milk. And particularly, what you know is that everything you have today can, at any moment, be completely taken away and destroyed. There is no security. You live as if you will be there tomorrow, while you know at the same time that you could not be there tomorrow. So that sense of dread and the sense of celebration both at the same time were very much a part of my experience.

GROSS: So did it make you fearful, growing up, and afraid to take risks?

PEREL: In my personal case, it made me counterphobic, which means that I am very fearful, but I live as if I'm fearless. And I took a lot of risks.

GROSS: OK, that seems like a paradox, yeah.

PEREL: Yes, yes, yes because for many people, acknowledging the fear and living by fear - you know, I would put it to you this way. In the camps, the vulnerable died, so it's the strong people who survived. Five years in a concentration camp, you cannot be weak. You cannot be vulnerable. And I think that I absorbed a little bit of that. You know, you knew that you have it, but that's not what you let - you don't let yourself be directed by that. And so you act as if you are fearless, while inside, you can be a shaking leaf. That's a little glimpse unto me.

GROSS: In your acknowledgements in your new book, you write, to my parents, who taught me to speak up and whose harrowing experience of betrayal showed me that there was always hope for healing, even if it's only partial. What is their betrayal that you're referring to?

PEREL: One day, I just said, you know, my parents were not betrayed by their partners. They were betrayed by humanity. And how do you come back from that and still think that the world is a place worth living in, that it's worth it to have children in it, to love, to make love, to celebrate life, to experience joy? You - this is resilience. This is having faith that it's worth it, that - because there were two kinds of people in my community, you know?

I often thought that there were people who did not die, and there were people who came back to life. And people who did not die often lived very tethered to the ground, very untrusting of the world, unable to rejoice, unable to experience pleasure because when you experience pleasure, it means that you're not on guard, and it's - and you're not vigilant. And the people who came back to life were people who had somehow found a way to experience the erotic as an antidote to death and to reclaim the passion for life.

And I don't think one was better than the other. I just think that some had the ability to still experience that passion. And for me, watching the - my parents and those people like them who really knew how to maintain themselves alive in the face of adversity and stay connected to that aliveness and that vitality is what I refer to when I look at crisis, when I look at how people kind of rise from the ashes of their relationship or of life. And when I feel that people learn to trust again, to love again, to make love again, I often think about them. They are kind of the marker for me.

GROSS: Since each of your parents were the sole survivors of their families, do you think that that affected how they raised you as their child and what the importance was for them of having children?

PEREL: So I have a brother, a dear brother, who is much older than me. He's 12 years older than me. And I think that many survivors had a child right after the war. Having a child was a sign that they were still human. After years of not having menstruation, after years of being dehumanized, the act of creating a child reconnects you with your humanity. And the children of survivors, I think, were often not just - they were miracles. They were miracles that we didn't all die, that the Jews would survive, that there was still a future, that the name would continue to exist. So I think that often as children of Holocaust survivors, we experience a sense of specialness. And we experience also the burden of that specialness that we have to live lives that are bigger than life, that we have to make up for all of the people who didn't make it, that we are symbols of revival. And...

GROSS: That's a lot of pressure.

PEREL: ...It is a lot of pressure. It's a conversation that many children of survivors have with each other. It's - I'm not alone in that at all because, you know, that - voila. That's it. You are - you're a miracle. You were not meant to be, and so many others were not. And then this is different if those parents had children before the war. That's yet another layer for some of us. Not me, but others.

GROSS: Is this a conversation you ever had with your parents?

PEREL: Many times I - my parents - among the group of survivors, there are those often who are seen as those who speak and those who do not speak, you know? And then, of course, what do they speak about? My parents had a way of telling more of the heroic stories rather than the victimization stories. They were storytellers. And people came to the house and listened to them. They were these amazing people.

You know, they - after the war, my parents were illegal refugees in Belgium for five years. The story doesn't end just when they come out of the camps. So they're hiding and they're living under the radar and continued for five more years, you know? I wasn't there yet, but that's part of the stories, too, you know? And we talked a lot. We talked a lot about how they came to Belgium, what their life was like, how they rebuild, what they think about when they think about the past. I went to Poland with my parents in '91 right after martial law lifted. I wanted to see the places where they came from. I've interviewed my parents. I've wanted to pass it on to my children. It's very much at the core of who I am.

When I say my parents encouraged me to speak the unspoken, yes, I think I have something that takes me to subjects that are often complex that I want to dig in, that I want to find the humanity and the compassion in these subjects rather than just looking at it from a harshly judgmental black-and-white point of view because I think they were on the other side of that and of people who just saw them and made an instant judgment about them. And I think they always encouraged that in me. And it's a proud legacy, I would say.

GROSS: Esther Perel, thank you so much for talking with us.

PEREL: My pleasure.

GROSS: Esther Perel is the author of the new book "The State Of Affairs: Rethinking Infidelity." After a break, we'll listen back to a 1988 interview with Pat DiNizio, the lead singer and main songwriter of the band The Smithereens. He died yesterday. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF CARL VERHEYEN'S "GOOD MORNING JUDGE")

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.