Other segments from the episode on October 23, 2009

Transcript

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20091023

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Looking Back On 'Wild Things' With Maurice Sendak

TERRY GROSS, host:

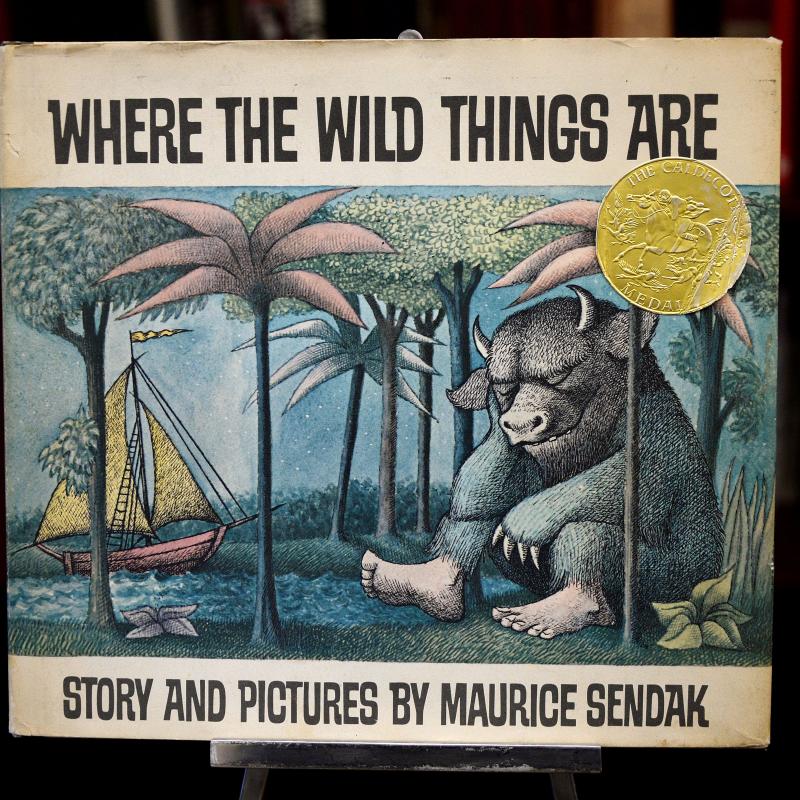

This is FRESH AIR. Iâm Terry Gross. Now that Maurice Sendakâs 1963

childrenâs book, âWhere the Wild Things Are,â has been adapted into a

film, weâre going to listen back to excerpts of interviews I recorded

with Sendak. Weâll start with our first conversation, back in 1986.

âWhere the Wild Things Areâ is part of a trilogy, with âIn the Night

Kitchenâ and âOutside Over There.â Sendakâs heroes and heroines are

frequently disobedient and have to contend with the demons that haunt

childhood. That made some of Sendakâs books controversial when they were

published. For instance, some authorities on childrenâs literature

advised parents against exposing their children to âWhere the Wild

Things Areâ because his illustrations of big, horned, fanged, clawed

creatures could terrify children.

Sendak told me that when he was young, adults looked like big and

grotesque creatures to him. He couldnât imagine ever becoming one.

Mr. MAURICE SENDAK (Author, âWhere the Wild Things Areâ): It was

inconceivable to me as a child that I would be an adult. I mean, one

assumed that would happen, but obviously it didnât happen, or if it did,

it happened when your back was turned, and then suddenly you were there.

So I couldnât have thought about it much.

GROSS: Because adults seemed really big and different, you couldnât

imagine becoming one?

Mr. SENDAK: They were awful. Yeah, I mean, they were mostly dreadful,

and if the option were to become an adult was to become another dreadful

creature, then best not, although I think there had to be a kind of

normal anticipation of that moment happening because being a child was

even worse.

I mean, being a child was being a child, was being a creature without

power, without pocket money, without escape routes of any kind. So I

didnât want to be a child.

I remember how much - when I was a small boy I was taken to see a

version of âPeter Pan.â I detested it. I mean, the sentimental idea that

anybody would want to remain a boy. I donât â I couldnât have thought it

out then, but I did later, certainly, that this was a conceit that could

only occur in the mind of a very sentimental writer, that any child

would want to remain in childhood. Itâs not possible. The wish is to get

out.

GROSS: Are there any memories that typify your childhood to you now,

looking back?

Mr. SENDAK: Well, itâs typically â30s in many ways in that I had a

series of long illnesses, but then there were no drugs, and there was no

penicillin, so kids all ended up having diphtheria, scarlet fever,

pneumonia, blah, blah, and I spent a lot of time being sick, as I

recollect, and there is the happy memory, actually, of being indoors and

watching â the window became my movie camera, my television set.

One of the happiest memories I have is when my grandmother would come to

stay with us on those occasions and she would put me on her lap, and

then she used the window shade like a magic lantern. Sheâd pull it down,

then Iâd hold my breath and sheâd pull it up and the same thing would be

there: a car, or my brother and sister making a snowman or whatever.

So happy memories of being indoors looking out of windows, and I think

itâs no accident that windows, or children looking out of windows or

going through windows or whatever, becomes an obsession in most of the

books Iâve written.

GROSS: A lot of your books deal with the children trying to overcome

certain fears, trying to get control of them. What were the things that

frightened you when you were a child yourself?

Mr. SENDAK: Well, odd things. I donât know if my books are about that,

by the way. I mean, they are probably partly that, but I donât set out

to write a book thatâs going to conquer fear or do anything but amuse or

entertain or distract a child. But my own fears were very peculiar. I

was terrified of the vacuum cleaner, you know, untraditionally.

I mean, people sit around saying, well, donât let kids do that, and

donât let kids do that, itâll be too frightening, but who would have

ever imagined anybody saying donât let a kid in the room with a vacuum

cleaner.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SENDAK: But when my mother plugged the vacuum cleaner in, and it was

those old-fashioned Hoovers, you know, the thing blew up visibly, and

the sight of that bag swelling used to just drive me right up the wall,

literally. I had to get out of the house, and I was sent to the

neighbors until she was all done.

âThe Invisible Manâ was one of the most terrifying of my nightmares and

I think definitely led me to being an insomniac for the rest of my life.

GROSS: The movie âThe Invisible Manâ?

Mr. SENDAK: The movie with Claude Rains. We were taken to see it, and I

remember coming home and being in shock, and it was from that moment on

that my sister had to stay with me until I fell asleep, because he could

be anywhere in the room.

I mean, there was no way you could say, well, you see, heâs not there,

you see hereâs not there. My answer was: Well, you canât see him, so

whatâs the big deal?

GROSS: You have three books which you consider your trilogy: âWhere the

Wild Things Are,â âThe Night Kitchenâ and âOutside Over There.â Are

there any themes that you think of holding these three books together as

a trilogy?

Mr. SENDAK: I think so. One of them â there are any number of them, but

one of them, which is most obvious, is that they all have to do with a

brief, inadvertent moment in a childâs life. What happens? Kids are safe

indoors, and mama turns her back for a minute, or papa turns his back

for a minute. Nothing big, no great shriek, no accident. Itâs more a

mental state. Itâs more an emotional moment which goes by unheard.

These are loving parents. These are not weird parents, but theyâre

parents who have to turn their backs for a second. Life does take them

up too occasionally, and in that second the kid has to make a decision,

all by him or herself without the experience which we have as adults or

the logic that tells them what to do. So they have to figure it out very

quick, and often they come up with very ludicrous and illogical

conclusions to a situation.

And all three of the children in these three books do, in fact, face

such a moment by themselves and have to decide what to do.

GROSS: In âWhere the Wild Things Areâ a young boy is sent up to his room

without supper, and heâs really angry at his mother. So he decides to

leave home and go to where the wild things are, and he becomes king of

the wild things, and the wild things are these wonderful monsters or

beasts that youâve created. What inspired the shape and the faces, the

bodies of the monsters?

Mr. SENDAK: Well, there was a lot of work on that, and I didnât want

them to be traditional monsters, like griffins and gorillas. Just like,

I wanted them to be very, very personal, and they had to come out of my

own particular life. And I remember it took a very long time until that

gestation occurred and when they began to appear on drawing paper and

they began to be what I liked, and it was only when I had them all that

I realized they were all my Jewish relatives.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SENDAK: They were all the adults who treated us in such silly

fashions when we were kids, and they were the real monsters of my

childhood. You know, people come on Sunday and wait to get fed, uncles

and aunts, and you used to get all dressed up, and youâd have to sit and

listen to their tedious conversation when you want to be with your

brother and sister and listening to the radio or whatever, and they all

say the same dumb thing while youâre beating time until food gets put on

the table: how big you are and you fat you got, and you look so good we

can eat you up. In fact, we knew they would because my mother was the

slowest cooker in Brooklyn, so if she didnât hurry up, they would eat us

up.

So the only entertainment was watching how â watching their bloodshot

eyes and how bad their teeth were. You know, children are monstrously

cruel about physical defects.

So my entertainment was to examine them closely, you know, the huge

nose, and the hair curling out of the nose and the weird mole on the

side of the head, and so you would glue in on that and then youâd talk

about it with your brother or sister later, and they became the wild

things.

GROSS: One of the things I love about the monsters in the book is that

theyâre really goofy. I mean, to me theyâre not really frightening.

Okay, granted, Iâm an adult, but still, thereâs something really kind of

goofy and playful and big and sloppy about them.

Mr. SENDAK: Thatâs true, but at the same time they are threatening. I

mean, if Max were not in control of them, they could indeed be in

control of him, and when they say oh, please donât go, weâll eat you up,

we love you so, they mean just that, and he knows that, and I think

children know that too, that the fun of that book is a perilous

tightrope between him being a little boy and very vulnerable to these

huge creatures and the absurdity of his having control over them by

staring into their yellow eyes. Itâs what every child would like, to

have control over such things.

Kids are not afraid of them because Max is not afraid of them, and see,

the kids glue in onto Max right away, and they follow him, and if heâs

okay, theyâre okay.

GROSS: âIn the Night Kitchen,â which is the second book of your trilogy,

when the book came out, Mickey, who is the main character in it, is nude

during part of it, and I understand that there were librarians who

actually blocked up the little infant penis so that children wouldnât be

exposed to it.

Mr. SENDAK: Yeah, he had to wear little diteys or diapers or shorts

before theyâd let the book into the library. We live in a very strange

society. I mean, I was outraged when that book came out, and there was a

such a hullabaloo over his genitals.

I mean, I assumed everybody knew little boys had that and that this

wasnât a breakthrough. The fact that people considered that outrageous -

incredible. I mean, you go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, you go to

the Frick, you go to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and thereâs a

Christ child with his penis. Itâs accepted in fine art, but somehow in

books for children, thereâs a taboo.

Well, the hell with that. I mean, I didnât set out to cause a scandal. I

set out to do a very particular work where he had to be naked in order

to confront a particular dream he was in. You donât go into a dream

wearing Fruit of the Loom underwear or PJs. You go tuto. You go

yourself, your being, and thatâs why he was naked, and it was idiocy. It

was incredible idiocy what went on over that book for many, many years

about Mickey being naked.

GROSS: The third book in your trilogy, âOutside Over There,â is about an

infant whoâs kidnapped by goblins and is rescued by his big sister.

Mr. SENDAK: Her big sister. Thatâs okay.

GROSS: Her big sister, yeah. When I was a kid, we were always warned

that certain people would kidnap you, and I think that that fear has

escalated a lot more since I was young. Did you grow in the Lindbergh

kidnapping period?

Mr. SENDAK: Yes, I did, and that book is a kind of, as you can say it,

homage to the Lindberg kidnapping and the anxiety that that provoked in

me as a child, but more than that, itâs a primal anxiety that children

have. Whether they lived through the Lindberg kidnapping or any real

kidnapping in the real world, the true anxiety is, will I be taken away?

Will my parents be taken away? When papa goes to work, does he really

come back at night? If mama leaves, how do I know sheâs going to come

back into the room?

These are of intense concern to children, and thatâs what itâs about.

Itâs not about the Lindbergh kidnapping. Itâs about the terrible feeling

of being abandoned.

Now, that book has had the most controversy of all the three, and it is

the book thatâs having the most troubled course in its life. I suspect

that that anxiety is so much of human nature, is so part of our lives,

that some people just simply donât want to consider it at all, and

again, they think best to protect their children from such visions when,

if my theories hold up, and I think they do after 30 years, children

have these visions whether you protect them from it or not.

And in âOutside Over There,â at least unlike real life, I give it a

happy ending. I mean, I revive Charlie Lindbergh, Jr. and bring him back

in the form of a little girl baby at the end of that book.

But it was a very important book to â not simply because of the

abandonment idea but the complex feeling of an older child in relation

to taking care of a younger child.

I lived with one. My nine-year-old sister had to take care of me, and

she loved me, but there were moments when she didnât love me at all and

wished me dead, and I think that is another normal and has to be

accepted as a normal attitude of children. Itâs not something to be

frightened of. Itâs just something they must get used to and live with.

GROSS: Can I ask you what books made the most impression on you when you

were growing up?

Mr. SENDAK: âMickey Mouse in Pygmylandâ was the first book. I adored it.

I didnât know it was a rip-off of âGulliverâs Travels.â Itâs Mickey

being in a place where they tie him up and walk all over him. It was a

great book.

I remember I drove my father crazy until he bought me a copy of âRobin

Hood,â which I saw in the stationery shop in Brooklyn, in Bensonhurst,

and the reason I wanted it, it had a beautiful, shiny white cover with

Errol Flynn on the cover in his Robin Hood uniform, because the movie

had just come out, and I saw that, and I had seen the movie, and I just

had to have that book. And it was 50 cents. I remember it.

And I literally drove him mad. I didnât care how mad he got, I just

besieged and I battered him down until I got â I still have that copy.

It meant so much to me to have that book and that jacket, and then when

I read it, or it was read to me, I was allowed to sniff the paper,

because the paper, the smell of cheap paper just â that was my fix. And

Iâve always thought when I smell books that have that smell, I think

thatâs Sherwood Forest.

GROSS: That interview with Maurice Sendak was recorded in 1986. The film

adaptation of his classic childrenâs book, âWhere the Wild Things Are,â

opened last week. Weâll hear a more recent interview with Sendak after a

break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Weâre listening back to conversations Iâve had over the years

with illustrator and author Maurice Sendak. His work for children, like

âWhere the Wild Things Are,â has a dark edge, but nothing quite as dark

as his book âBrundibar,â a collaboration with writer Tony Kushner, whoâs

best known for his play âAngels in America.â

âBrundibarâ is an adaptation of a childrenâs opera that was originally

performed by children in the Nazi concentration camp Theresienstadt. The

opera is a parable about evil that was written in 1938 by a composer who

was killed in the gas chambers.

A Sendak-Kushner adaptation of the opera was staged in 2003 by the

Chicago Opera Theater. Sendak was the director and designer. Hereâs the

opening scene from an earlier recording of âBrundibar,â recorded in

Prague.

(Soundbite of opera, âBrundibarâ)

GROSS: When I spoke with Maurice Sendak in 2003, he told me about the

origins of âBrundibarâ and why children in the Nazi concentration camp

performed it.

Mr. SENDAK: This opera was written by Hans Krasa, a very young Czech

composer, and it was written for children, Jewish children, in an orphan

asylum in Prague to amuse them. It was a contest, who could write the

prettiest opera for the children. And at that very same point, the Nazis

entered the country and the orphanage was emptied and the children but

into Theresienstadt, the camp, and he was too, as was the librettist,

and it became a show camp. It became known as Hitlerâs favorite camp. He

set up in such a way and made a film of how well the Jews were being

treated, and the gypsies and the homosexuals.

And so he set this up to prove to the Red Cross and diplomats who were

traveling the world to come by, see a show, and see how happy everybody

was, and itâs in the film. You see the children singing in the last

portion of the opera.

So they all sat there. It was performed 55 times, a huge success, this

little opera, which is about 45 minutes in length. Thatâs the story.

Hans Frasa was murdered too, as was the librettist, as was, well, mostly

everybody in the camp.

It was an elitist camp. You had Bauhaus workers there. You had artists,

people teaching the children there, intellects. It was a special camp,

but it ended the same way for all of them.

GROSS: So the performances were for visiting diplomats to show off the

camp?

Mr. SENDAK: Yeah, yeah.

GROSS: Do you know if they fell for it?

Mr. SENDAK: Oh yeah. Oh, absolutely they fell for it. The streets were

cleaned. Trees were planted. All the children were given clean clothes.

Everything was swept up, and they went, and you had a pass to get in to

see âBrundibar.â

GROSS: Tell us the story thatâs told in the opera that you tell in the

book.

Mr. SENDAK: This was directly written for children and the limitations

of children. (Unintelligible) singing voices. Mostly, itâs sort of like

a singspiel(ph), which is like a Mozart opera, the singspiel, where you

talk over the music rather than actually sing, and those who could sing

sang, and the music is astonishing.

He was in his 30s. So you hear Janacek, and you hear Weill, and you hear

Gershwin, and you hear Ravel, and just like all of young artists steal

like crazy until we make ourselves up as artists, you hear all these

wonderful sounds.

And the story is ultra-simple so the children could follow it and

produce the tale, which has to do with a little brother and sister whose

mother is ill, and the doctor says unless they get milk for her, she

wonât last.

So they go out into the world, which is in my case Prague, into the city

proper. Please, somebody give us money to buy milk for mommy. And nobody

will, and in the streets of Prague, on a specific corner is Brundibar,

who is an organ grinder, mean, mean, and they stay all night in the

street by themselves. A cat and a bird and a dog come to their

assistance and say, look, letâs pull this together. The two of you canât

do this by yourselves. Letâs get all the kids in town, and the animals

convince them to come and help these kids.

So they all come to the town square, 300 of them, and they say to

Brundibar, we want to sing, and we donât care about money. We just want

to sing. And Brundibar says, no, no, get the hell out of here, and the

townspeople say, let the kids do it. And they sing a lullaby, which is,

like, extraordinary to hear it.

And people are captivated, and they fill the milk can with coins.

Theyâve made it. They have enough money now, but Brundibar sneaks in and

grabs the can, rushes off and steals their money, and the whole town

chases Brundibar, and they catch him, and they beat him up, and the kids

get their money back and buy the milk, come home triumphant and save

their mama, and thatâs the story.

GROSS: But thereâs an epilogue to the story. Thereâs a little poem at

the end. Could you read that for us?

Mr. SENDAK: Sure, sure.

GROSS: And just, you know, reminder, this is written while Hitler is

coming to power.

Mr. SENDAK: Exactly, and the fact that it is impossible for me to doubt

that the children knew what their fate was. Imagine standing up on the

stage and singing about brotherhood, and if we all hang together weâre

going to succeed and the bully will not â and knowing that as soon as

this audience left, kaput, their lives are finished. I canât even grasp

that now. Iâve been studying and working on this for over three years.

Okay, so we just turn the page on the big happy ending where everything

is wonderful and safe, and mommy is alive, and then thereâs a little

coda at the end, which was written by Tony, basically. Itâs not in the

opera. And it says â this is Brundibar talking: They believe theyâve won

the fight. They believe Iâm gone, not quite. Nothing ever works out

neatly. Bullies donât give up completely. One departs, the next appears,

and we shall meet again, my dears. Though I go, I wonât go far. Iâll be

back, love Brundibar.

GROSS: Yeah, thatâs kind of chilling.

Mr. SENDAK: Yeah.

GROSS: Maurice Sendak, talking about his book and opera âBrundibarâ in

2003. The movie adaptation of his 1963 book âWhere the Wild Things Areâ

is in theaters now. Weâll hear more from Sendak in the second half of

FRESH AIR. This is NPR, National Public Radio.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

The movie adaptation of Maurice Sendak's children's book "Where the Wild

Things Are" opened last week. Sendak's writing and illustrations depict

childhood as a place where there is often sadness and fear, and

sometimes even monsters. "Where the Wild Things Are" is part of a

trilogy with "In the Night Kitchen" and "Outside Over There."

When I spoke with Sendak in 1993, he just completed his first book that

wasnât about middle class kids. That book, "We Are All in the Dumps with

Jack and Guy" is set in an urban landscape and deals with homelessness,

sickness and hunger. It's based on two English nursery rhymes. I asked

him to recite them.

Mr. SENDAK: We are all in the dumps. For diamonds are trumps. The

kittens have gone to St. Paul's. The babies are bit. The moon's in a

fit. And the houses are built without walls. First one.

Second one. Jack and Guy went out in the rye and they found a little boy

with one black eye. Come says Jack. Let's knock him on the head. No says

Guy. Let's buy him some bread. You buy one loaf and Iâll buy two and

we'll bring him up as other folk do.

GROSS: The first rhyme that you recited...

Mr. SENDAK: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: I wouldn't have known what to make of that. I'd have to say...

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: ...it wouldnât have made any sense to me.

Mr. SENDAK: Well...

GROSS: Do you want to recite it one more time?

Mr. SENDAK: Sure.

(Soundbite of clears throat)

Mr. SENDAK: Well, see there are clues in it for an illustrator. We are

all in the dumps.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. SENDAK: For diamonds are trumps. The kittens are gone to St. Paul's.

The babies are bit. The moon's in a fit. And the houses are built

without walls.

Now, I think it's extraordinarily beautiful poetry. But if I haiku what

does it mean, well I'm faced with a bridge games - diamonds are trumps.

That means somewhere in this book somebody's playing bridge.

Not being a card player, that doesnât turn me on. So I had to learn how

to play bridge. The moon's in a fit. You have to figure out why the moon

is in a fit. What does it mean the kittens are gone to St. Paul's? I

mean what is St. Paul's mean to American children, primarily? And the

astonishing extraordinary line, the houses are built without walls. I

mean that's what moved me all these years to make this work for me.

GROSS: So what did that come to mean to you, the houses are built

without walls?

Mr. SENDAK: Well, it meant, finally, kids who have no place to live.

This really started back in Los Angeles or at least one detail and a

significant one began in Los Angeles years ago. I was working on an

opera - the LA opera, and we came home late from a rehearsal and I was

driven back to my hotel and we passed down some very, very posh streets

in Beverly Hills. Maybe it was Rodeo Drive but I couldnât swear to it.

And there past midnight, on the street, in this posh section of town was

a just a dilapidated ruined cardboard box with two dirty naked kids feet

sticking out.

The juxtaposition was astonishing. It's as though when everybody stopped

shopping and gone home, then these kids came out - or people came out.

But it astonished me to see that juxtaposition. I got interested and I

got a book on Rio - Rio de Janeiro - and discovered that there is a

ringed round(ph) well known shanty town, kid's town, around the city,

and kids are abandoned.

They have little girls sold into prostitution. Little boys run away from

abuse - from being abused at home and they make their own cities. And

they're as cruel to each other as any adults can be and their lives are

very, very brief. And they live in tin cans and cardboard houses and rag

huts, and I suddenly began to see what dumps is - we are all in the

dumps.

Back in the 60s that, of course, meant you know, if youâre in therapy

dumps means youâre in depression, which is probably why I couldnât make

anything sound out of it back then. Now dumps literally means the world.

GROSS: Your new book deals with some real world fears like,

homelessness...

Mr. SENDAK: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And just being scared by what could happen to you as a kid now.

What were the real big events in your life that you found really

frightening when you were young?

Mr. SENDAK: When I was young, the big events were being sick and being

expected to die, and knowing that at a very early age, I might. And this

was spoken. My parents were very indiscrete. My parents came from a

foreign country. They were immigrants. They didnât know about Freud.

They didnât know about what to say or not to say in front of children.

So - and they loved us - me, my brother and my sister, but that I

suffered a good deal from very severe illnesses, not untypical of '30s

children when there were no sulfa drugs and there wasnât penicillin and

you went through all the dire illnesses and sometimes you just croaked.

So it was the awareness at a very early age of mortality which pervaded

my soul apparently and I think provided me with the basic ingredients of

being an artist. That was critical and knowing that I was vulnerable and

that other children were vulnerable.

GROSS: What did you have? What it was that...

Mr. SENDAK: Oh, you know, scarlet fever and pneumonia twice and whooping

cough and chicken pox. It was the pneumonia and the scarlet fever that

really nearly did me in.

GROSS: Were you carefully watched over by your parents when you were

sick?

Mr. SENDAK: I was so carefully watched I practically - they practically

killed me with watching over me, so I was delicate. I was very delicate.

And was not allowed to participate in street games and so then a lot of

my early child was immediately spent in inventing and imagining.

GROSS: In those days when you were sick and everybody was worried about

you dying, did you have any sense of what death was?

Mr. SENDAK: I donât remember that. But I do remember I was a very close

companion to death. And I remember a game my father played with me -

which you would not exactly call a death game but did move in that

direction. Which was that if I lay in bed, which I spent a lot of time

doing, and remember in one particular place we lived in Brooklyn. We

moved quite frequently because of financial problems. And just opposite

the foot of my bed was a window looking out in the backyard facing a

just very boring brick wall.

And he said if you - to me - if you looked and didnât blink, if you saw

an angel, you'd be a very, very lucky child. And so I did that

frequently. Of course, I would always blink because it hurt not to

blink. And then you didnât see it and he'd say well, you blinked didnât

you? And I'd say yes. And I remember once I didnât blink and saw it - or

I imagined I saw it. But it's the memory of it is so vivid I could even

describe it to you.

GROSS: Would you?

Mr. SENDAK: Well, I was lying in the bed obviously, starring out the

window. My eyelids aching. My eyes aching, staring, staring, staring.

And something very large like - almost like a dirigible but it wasnât a

dirigible because it was right past my window. It was a slow-moving

angel. She - he - whatever, moved very gracefully and slowly coming from

left, going across to right, not turning to observe me at all. I donât

have memory of the face but I remember a memory of the hair, the body

and the wings. I was - it took my breath away. It just moved so slowly

that I could examine it quite minutely. And then I shrieked and hollered

and my father came in and I said I saw it. And he said I was a very

lucky kid.

You will have noticed angels in "We Are All In The Dumps." I love

angels. About to say obsessed, that's a hyperbole. I'm not obsessed with

angels but I do adore angels. I've never drawn them in a book and they

do appear in the new book - primarily because so many people have died

recently that I have populated my book with their spirits floating

around and they're all reading The New York Times because I can...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SENDAK: Even up there you got to figure out what's going on every

day.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: So when you saw the angel, did you think that that was a sign

that you were going to live or that something wonderful was going to

happen?

Mr. SENDAK: Well, I think it put me in alliance with death things, with

important things. I can't really describe it. I really can't tell you

what it meant. Very internal feeling. But it came out of such a complex

awareness as a child of the fragility of life.

There is a story which I can't prove, but I was told, that at a very

early age my parents dressed me. It's a religious custom or superstition

from the old country. They dressed me all in white, from top to toe, so

that if God is watching he would've thought me already an angel and he

would not pluck me - and I wouldnât die, in other words. I would be a

fraudulent angel.

This is a superstition and it does occur in old villages in the old

country. I donât know that it happened to me. But it's significant that

it was a family story, so that it told me how forcefully they were

concerned about me.

GROSS: We're listening to a 1993 interview with Maurice Sendak. The

movie adaptation of Sendak's book "Where The Wild Things Are" opened

last week. We'll hear more of the Sendak interview after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Let's get back to our 1993 interview with Maurice Sendak.

Earlier, we were talking about how he was often sick as a child; some of

his illnesses were life threatening.

Did you see your parents as being really capable parents who could help

fend off death or fend off what other problems they had?

Mr. SENDAK: No. No, because they were so vulnerable to problems. They

caved in on problems all the time. So I did not see them. And this is

not a criticism of them. Their lives were extremely hard. But no. No. I

did not see them that way.

GROSS: Now, they were from Poland?

Mr. SENDAK: They were from Poland. Yeah.

GROSS: And they fled before World War I?

Mr. SENDAK: Yes they did. Just before World War I. They didnât flee. My

father left on a lark.

GROSS: Oh. Well, what was that?

Mr. SENDAK: He had no cause to come here. My grandfather was a rabbi,

and he was the youngest son and he was obviously the spoiled younger son

of my grandmother. And he actually fell in love with a young woman and

it became a little bit scandalous and she was put on a boat and shipped

off to America. And he sulked and pouted and got money out of his

siblings and got on another boat to follow her here. And his family was

appalled at his behavior.

Because of that trivial behavior, he was the only survivor of his entire

family. I mean all of my uncles and aunts and all of the children were

destroyed in concentration camps. My father's grief - his entire life -

was that his survival was based on such a trivial impulse. It really did

cause him a lot of grief, especially when he became older.

GROSS: You grew up before the holocaust. Was he still really regretful

about...

Mr. SENDAK: Oh, he was terribly regretful and guilty and he had survivor

guilt and did my mother, who had much less cause because she was shipped

off when she was about 17 to come to America. She was uneducated,

untrained in anything. She was a girl. My grandfather on her side, also

a rabbi, had died a very early age of a coronary and there was no money

to take care of everybody - so she was sent here to do it, to work hard,

earn money and then bring them over. It's typical.

She met my father, they married and all the first income was spent on

bringing one aunt, then an uncle, then another uncle, then another aunt,

then my grandmother, until finally all but one brother on her side were

all here. And then they were going to turn to my father side, and then

it was too late. That was in the '30s. There was no getting Jews out of

Europe at that point. And so growing up during the war, that was tough -

having to live through that and all its complexity. It colors your life

forever.

GROSS: Did your parents talk to you much about the old country?

Mr. SENDAK: Oh yeah. Thank goodness. And when my father was - the last

year of his life - paradoxically we had a wonderful time. I took his

biography down, which was wonderful. A lot of it was fantasy and a lot

of it was reality, but I was...

GROSS: His biography?

Mr. SENDAK: Yeah. His...

GROSS: He wrote a biography?

Mr. SENDAK: He wrote a biography, which is not published. He did write a

fairytale, which I translated with the help of somebody else and

illustrated and that was published just before his death.

GROSS: Right. I - right.

Mr. SENDAK: It's called "In Grandpa's House." But his biography is not

published and I donât intend to have it published. Itâs a private family

chronicle. We didnât get much of my motherâs life. My mother was silent

about that period of her life.

GROSS: I think thereâs a lot of people from Eastern Europe who came to

America were. Did they seem like aliens to you because, I donât know,

they probably - did they speak more Yiddishâ¦

Mr. SENDAK: Yes, the spoke more Yiddish. I spoke Yiddish as a child. My

parents spoke English very, very late and very poorly. And we lived in a

part of Brooklyn, which was teeming with immigrants, either people from

Eastern Europe, Jews or Sicilians and I couldnât tell the difference. I

mean, we lived next to the Sicilians and I had a real â it sounds like

coy conceit, but itâs a fact. I had a real confusion because right

across the hall from us was my best friend at one place we lived,

Carmine(ph), and his sisters and brothers and his huge mother and huge

father just across the hall. And I used to run across the hall because

they had un-Kosher food.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SENDAK: It was much better, much better than Kosher food because it

was â it was pasta. It was great Italian cooking. And they laughed and

they drank wine, and they grabbed me, and I sat on their laps and they

had a hell of a good time. And then you come back to my house and you

have this sober cuisine and not so rambunctious family life. And I

really did have a confusion that Italians were happy Jews, that they

were a sect.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Oh, thatâs (unintelligible).

Mr. SENDAK: And that I would have a choice â that I would have a choiceâ¦

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SENDAK: â¦after my bar mitzvah to belong to either the sober sect or

the happy sect.

GROSS: And there must be different synagogue where they had pasta.

Mr. SENDAK: Yeah. I was a dumb kid, let me tell you.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SENDAK: I mean, all the parents were looked alike. They all wore the

same dull, black dresses and you couldnât tell the difference, not to

me.

GROSS: I remember I interviewed you â oh, I donât know - eight years ago

or something. Something that you said really stuck with me. You were

talking about the monsters in âWhere The Wild Things Are,â and you were

saying that when you were young, the monsters were just adults. They

were people with like moles on their faces and hairs growing out of

their noses andâ¦

Mr. SENDAK: Yeah, old relatives.

GROSS: Yeah, old relatives, exactly, exactly, and that, that really

struck a chord.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: And then I started thinking well, Iâm one of those people now. I

mean, I donât know if I actually have hair growing out of my nose but,

you know, I have some of those things that Iâm sure kind of like scare

kids.

Mr. SENDAK: Oh sure.

GROSS: And do you have a sense of yourself as that, tooâ¦

Mr. SENDAK: Of course.

GROSS: of like, you know, a monster to some kids?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SENDAK: Of course, I am. I see it in their eyes. When Iâm

autographing books, which I donât like to do much anymore and children

are shoved at me.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. SENDAK: They have no idea why theyâre on the line. Theyâd much

rather be in the bathroom.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SENDAK: And theyâre standing on line and theyâre being told

something which is so frightening and confusing, which is being told by

mom or dad. This is a man youâd like so much, honey. This is a man who

did your favorite book. And they clutch their book even closer, that

really means heâs going to take it away. Because if this is the manâs

favorite book then heâs going to take your bookâ¦

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SENDAK: And a look of alarm and the tears and they stare at me -

like pure hatred. Who is this elderly, short man sitting behind the desk

whoâs going to take their book away? Then on top of that the parents are

like, give them your book, honey. He wants to write something in it.

Although theyâve been told donât write in a book. Okay. Why then is it

all right for a perfect stranger to write in their book. Itâs horrible

for them. And I become horrible unwittingly. I make children cry.

GROSS: They cry whenâ¦

Mr. SENDAK: They cry when they meet me because they donât know what Iâm

doing. And only when their â itâs quicker with girls because girls are

smarter than boys. We all know that. They grow up faster. And girls, by

the time theyâre seven or eight, already know the business of

autographing and what it means. Boys donât till theyâre about 40 I

think. And so, theyâll pull it away. Thereâs only one child who ever had

the courage and his father was urging him forward, urging him forward. I

can see the hesitation. I just felt so bad for the kid and I put my hand

on the book to help draw it away from him. And he literally screamed and

said â donât crap up my book.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SENDAK: It was the bravest, the bravest cry I have ever heard. I

nearly wept.

GROSS: What did you do?

Mr. SENDAK: I took the father aside because I think, I think the father

was going to kill the kid because heâd embarrassed him and made

everybody laughed. And I had to sit down and say, how great I thought

his kid was and not to be angry with him because the child just didnât

understand what this whole nonsense, this social nonsense of

autographing was all about. And it would be criminal to punish him for

this.

GROSS: This is great every time you do a book signing itâs kind of like

dysfunctional family America.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SENDAK: Thatâs right - becomes into psychiatric sessions.

GROSS: You must feel awful though, you know, because youâre being

misunderstood by the kids who love your book.

Mr. SENDAK: Well, frankly thatâs why I do not visit children in

classrooms. Thatâs why I stopped autographing, for the most part, for

that very, very reason. Itâs such a paradox, that I, who adore them and

Iâm interested in their welfare, should become their enemy. Itâs only

because itâs set up that way. If Iâm to visit a school theyâre all

warned, threatened and brow-beaten for three days before I get there.

Now I want all of you to be niceâ¦

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SENDAK: â¦and you must raise your hand and I want everyone to go to

the bathroom before Mr. Sendak comes.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SENDAK: I mean, their lives are ruined. So, why should I be the

person who does that to them?

GROSS: Maurice Sendak recorded in 1993. The movie adaptation of his book

âWhere the Wild Things Are,â opened last week. This is FRESH AIR.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

114044628

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20091023

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Amelia: A Biopic With Very Little Life

TERRY GROSS, host:

A new movie opened today about the American pilot Amelia Earhart. She

went missing in 1937, while attempting to be the first woman to fly

around the world. Hillary Swank plays Earhart. The film is directed by

Mira Nair and also stars Richard Gere as her husband.

Film critic David Edelstein has the review.

DAVID EDELSTEIN: The life of Amelia Earhart is so endlessly resonant, so

rich in mystery and irony, that itâs hard to forgive the makers of the

biopic âAmelia,â for getting her spirit dead wrong. The facts are all

here but the movie is a blueprint, it never breathes. It starts with a

reporter firing a question at Hilary Swank as Earhart, aka Mrs. George

Putnam, as sheâs about to embark on an around-the-world flight. He says

â this is the first line of the film â after this around-the-world

flight, Mrs. Putnam, are you going to give up long-distance flying?

Welcome to biopic country, where every lineâs a billboard. After that,

the film leaps back and forth between that flight â which, of course,

was Earhartâs last â and the years leading up to it. When Earhart passes

over giraffes in Africa, she marvels, look how free they are. No

schedules to keep. Then, in a flashback, she has to deal with schedules,

with people who want things from her, like Richard Gere as the publisher

Putnam, who begs her to marry him. I want to be free, George, she writes

in one of many voice-overs from her letters, to be a vagabond of the

air. The plane soars, sheep part in its wake and Swank gazes in vagabond

wonderment, remembering herself as a little girl on a horse in a field

racing a prop plane. I had to fly, she narrates. Itâs the difference,

she says, between a life of three dimensions and quote âa life

imprisoned in safety."

The movie is imprisoned in safety. The script by Ron Bass and Anna

Hamilton Phelan makes gestures in the right direction. It touches on the

most modern aspect of Earhartâs story: that from the get-go the image of

this would-be free spirit was marketed like crazy. Putnam functioned as

Earhartâs Madison Avenue Svengali, although the filmmakers canât bring

themselves to condemn him.

Heâs a tender father/lover who just happens to want Amelia to make

money. This is America, he keeps reminding her and itâs dollars that

allow her to fly. But Amelia boasts some of the most horrific examples

of biopic dialogue Iâve ever heard. When Amelia canât decide what to do

about her adulterous love for Gene Vidal, played by Ewan McGregor, he

says, just ask yourself, and Amelia says, Iâm not sure who that is

anymore. This is a very dull triangle: Amelia, Putnam, and Vidal, whose

little son Gore is comforted by Earhart when heâs scared of some tiger

wallpaper. The conflict comes to a head when the three debate the safety

of the final leg of that around-the-world flight.

(Soundbite of movie, âAmeliaâ)

Mr. EWAN MCGREGOR (Actor): (As Gene Vidal) The closest land west of

Hawaii is beyond the range of the Electra.

Mr. RICHARD GERE (Actor): (As George Putnam) Sheâll refuel in the air.

Mr. MCGREGOR: (As Gene Vidal) She doesnât have the flying skills.

Mr. GERE: (As George Putnam) Sheâs taking bigger risks.

Mr. MCGREGOR: (As Gene Vidal) Yes. Iâm aware of that. Donât be so proud

of it.

Ms. HILARY SWANK (Actor): (As Amelia Earhart) I understand the danger

fellows. Iâve studied the root. What have you come up with?

Mr. MCGREGOR: (As Gene Vidal) This is Howland Island. Itâs halfway

between Honolulu and New Guinea. Thereâs no elevation, no trees, hardly

anyone knows or cares that it exists. It would be almost impossible to

spot from the air. Itâs really tiny like a grain of sand in a thousand

miles of nowhere. If you miss this island, youâre out of fuel with 2,000

miles to go.

Ms. SWANK: (As Amelia Earhart) But Iâll have Fred Noonan, the best

celestial navigator around.

Mr. GERE: (As George Putnam) In fact sheâs taking Fred along for the

whole trip.

Ms. SWANK: (As Amelia Earhart) Giving up my little arrogance about solo.

Safety first, yes?

EDELSTEIN: The navigator, Fred, is an alcoholic, played by Christopher

Eccleston, who has more chemistry in his brief scenes with Swank than

either Gere, whoâs trying to dampen his sex appeal, or McGregor, who

jiggles his head like a parody of a handsome man. But then, Swank rarely

has chemistry with other actors. In her best performances, she has a

gift for pulling you into her charactersâ heads, for making their dreams

almost tactile. Sheâs certainly transformed herself. Iâm not sure if her

teeth have been artificially enlarged or sheâs lost so much weight that

thereâs nothing left of her but cheekbones and choppers - all sharp

angles with a dash of androgyny. But the movie has no texture for her to

play off. A director, like âThe Hurt Lockerâs,â Kathryn Bigelow, might

have lightly fetishized the planes so that you felt in your bones why

Earhart had to put herself in the air. But Mira Nair has no connection

to this material. The only emotion is in Gabriel Yahredâs old-fashioned

romantic score, which ladles on the strings.

Apart from a great scene with a stout, throaty Cherry Jones as Eleanor

Roosevelt, the only time Amelia even has a present tense is in the last

10 minutes, when Earhart is over the ocean and running out of fuel. What

a horrible irony: The story of this great American female icon comes to

life only when sheâs on the brink of death.

GROSS: David Edelstein is film critic for New York Magazine. You can

download podcasts of our show on our Web site freshair.npr.org.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

114074152

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.