Other segments from the episode on April 13, 2016

Transcript

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. We're going to talk about a subject that you probably never think about, the huge distances that the components of your smartphone, the beans in your coffee, the can that your soda is in - even the socks in your drawer - the distance they've traveled before you purchased them. And we're going to talk about the consequences of all that transportation. Think of it as your transportation footprint.

My guest, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Edward Humes, is the author of the new book "Door To Door," which he describes as a transportation detective story about the hidden characters, locations, myths and machinery driving our buy-it-now, same-day delivery, traffic-packed world. Humes is interested in the hidden price we pay for the things we take for granted. His previous book, "Garbology," was about the afterlife of our trash. Edward Humes, welcome back to FRESH AIR. Let's start with your morning cup of coffee. Simple thing, coffee - how does transportation figure into your morning cup?

EDWARD HUMES: Let's just look at the beans - to blend the beans - and I buy it by the bag. There's going to be about 30,000 miles accumulated over the course of the transportation of that coffee from various countries, brokered nations. It's going to be shipped by mega-container ships, by trucks, by rail perhaps. The particular French roast I looked at was - it came out around roughly 30,000 miles. And that's just for the beans to get from the point of origin to my house. And that's not counting the water used to make the coffee, which is also transported, the electricity that powers my coffeemaker, the coffeemaker itself, the filter, the packaging. If you start adding in all that, your cup of coffee's traveled a couple of times around the world before, you know, you take your first sip.

GROSS: Why do I care?

HUMES: Well, I think it's relevant to know where your stuff comes from. I mean, that was what I started writing this book in order to do because I was surprisingly ignorant about how things come to us and what it takes to keep your home supplied with things like coffee or socks or smartphones, whatever product you want to look at. There's a huge transportation footprint. And there's a huge cost attached to that. We live in a very unusual world unlike previous eras, where the more distance you packed into the thing that you were obtaining, the greater the the cost and the greater the risk.

Now, we've kind of flipped that in a very remarkable way. We achieve lower costs and efficiencies through embedding vast amounts of transportation in our everyday products rather than just the rare imports that we used to get over long distances. But there is a hidden cost to that in terms of the impact on the environment, on resources, on sort of hidden costs that aren't accounted for in the price of our goods. And we should very much care because it's a growing impact on our lives, on the flow of traffic when you try to drive to work, as we transition into this digital economy where we're purchasing more and more products online and adding even more miles and trips into the process of getting stuff.

GROSS: Let's look at something else and look at the transportation behind it. Let's look at the iPhone, which is one of the things you write about in the book. Just the components themselves have traveled from around the world. Do you want to just go through some of the distances just the components of the iPhone have traveled?

HUMES: Well, sure, I mean, there's multiple countries, islands, continents involved in the sourcing of the parts of an iPhone. I actually followed one assembly inside the phone - the home button, which also has a touch ID sensor. And you would think, oh, well, the parts all must be assembled in one place and then put together. But it doesn't work that way. The actual glass cover, the sapphire - synthetic sapphire that is the button - comes from one place. And that's sent to the next factory, which turns it into an assembly and adds a little circuit.

And then it goes to another country, and - or it may even go back to the same place again for another part to be added because the expertise has been spread around the world. And by the time you finish this trip tick that this little assembly takes, there's something like 12,000 of miles embedded in the homely little button that goes on your phone. And the logistics behind the fully assembled phone is something like 160,000 miles. And that's just for the parts. It doesn't even consider the raw materials, the precious metals and the rare earth elements and all the other things that have to go in.

And by the the time you factor in that, now you've, you know, accumulated enough mileage to travel to the moon for your phone - for your device. And everything is so diffuse now in how our products are assembled that we've created a huge dependence on transportation technology to carry through the day. And we couldn't really have many of the products we use every day without that sort of immense system moving things around in the background below our level of awareness.

GROSS: You said the big revolution in the way we move stuff around is the shipping container. How did the shipping container change our ability to have this kind of, like, global consumer economy?

HUMES: Well, it really - that's a hot political topic - all these trade agreements right now. But the humble and low-tech idea of a shipping container really was what enabled the offshoring and the outsourcing. You know, back in the - before the era of container ships, the leading technology company in the U.S. was RCA. And they built every aspect of a television, every circuit, every tube. They even had a furniture division that made the wooden cabinet that the TV - everything was vertically integrated. And that made the most economic sense then.

And one of the reasons for that was because shipping was so unreliable and expensive. Ships were loaded like you pack your trunk to go on vacation with the family. And you're jamming suitcases in every which way. And every one's shaped a little different. Nothing packs well. You forget stuff. That's how ships were loaded. You had gangs of longshoremen carrying stuff on ship and packing it into big holes. And that's the way it was for thousands of years of maritime trade. And now somebody gets the idea, well, what if we have a more standardized container, a big metal box? And you pack it at the source with stuff, and you lock it up so it's secure. And you don't have theft because it's sealed. And you don't have loss because you have a big container rather than small parcels. And most importantly, you can build a ship that is designed to just slide these things in on rails and drop them in.

And now suddenly, a vast ship that would take days and days to load up can be loaded in a fraction of the time with a fraction of the risk. And time - you know, shipping time is everything. The quicker you can get something moving and to its destination, the less the cost. And so that's why we've seen the rise from small cargo vessels that could carry hundreds of containers to vessels that can carry 20,000 containers and, you know, move enough to stock five or six Wal-Mart superstores at a pop. The economics of that are really clear.

GROSS: So these container ships are huge. Have you been on one?

HUMES: I have been close to them. And I tried. I went out with the port pilots at the Port of Long Beach and Los Angeles. And those are the biggest port complex in North America. And they see a lot of these container ships, and - but the crews that come to ports don't know the idiosyncracies of every port. And here you have these vast ships. And the last few miles of the global crossing, they have to hand over control to these pilots. And they go racing out in these boats. And it's such a mix of high-tech and low-tech because they have all this GPS and these guidance systems. And then they pull alongside these vessels that, as you get closer, are so vast. They're, you know, eight, 10, sometimes 15 stories tall with the containers loaded on their deck. And it's like a floating building. And this little boat's bobbing along.

And suddenly, a hatch opens. A rope ladder comes down (laughter). And, like, he's stepping off - as casually as if he was stepping off the curb into the street, this pilot just grabs this rope ladder and starts clambering up the side of this vertical steel wall that could crush him like an ant with one wrong step. And he goes on, and he brings it to the port through this very convoluted and difficult passage. These are ships that can be as big as two football fields, both in width and length. And in some places, he'll have the clearance that would be the equivalent of driving for miles with one foot clearance on either side of your car.

GROSS: So these huge container ships are an essential part of the global economy. They're an essential part of us getting all the goods that we buy and having, as you put it, the door-to-door economy. But there's a price we pay for it too. And part of that price is the fuel. What kind of fuel do these container ships use? And why is this considered, like, one of the dirtiest fuels?

HUMES: They call it bunker fuel. And it's basically the stuff that's left over after you've refined everything of value out of petroleum. And these ships - these big container ships don't burn it by the gallon. They burn it by the ton. You know, and they can go through 200 tons of this stuff in a day sailing. And the emissions from it are horrific. It's the consistency of asphalt. You could actually walk on this fuel when it's in the tank. But they heat it up so that it becomes a fluid. And then they can burn it. And there's 6,000 total in the worldwide fleet.

If you take 160 of them, the emissions from just those vessels, of the type of emissions that cause smog and particulate pollution, those 160 mega ships will be the equivalent of the emissions of all the cars in the world. And that's just a tiny fraction of the worldwide fleet. Together, the cargo fleet generates about 2 to 3 percent of world carbon emissions, which would - if that fleet were a country, it would put them in the top 10 emitters of carbon dioxide in the world. In fact, it would put it ahead of Germany - the fourth-largest economy in the world.

So they are prodigious polluters. And the oddest thing about this is that it's all off the books when we look at countries and businesses' carbon footprints because for it to count in the global assessment of carbon pollution, it has to belong to a country. But when these ships are at sea and beyond national boundaries, their emissions aren't part of that accounting. So this tremendous impact doesn't even figure in our calculations about, for instance, the carbon footprint of a product or a country or a business.

GROSS: Wow, that's kind of crazy.

HUMES: (Laughter) Yeah, isn't it?

GROSS: Yeah, well, I'm thinking, you know, you live in Southern California. So you have the benefit of the freeway traffic and two big container ship ports. So that's - that's a lot of emissions.

HUMES: It is. And actually, the port has - the ports, the twin ports, have been trying to rein some of that in. And there's been a lot of improvement actually, in part because they were prodded by lawsuits, in part because the state and the nation now has imposed a rule where these ships must burn cleaner fuel when they get within 200 miles of land. And of course, they get around that by - if they're going to - there's always a waiting queue to get into the port. So they'll linger at 201 miles (laughter) and keep burning the dirty fuel until they absolutely have to cross the line and then come in. But it still has made for a considerable improvement in air quality, at least in terms of the emissions from the port.

GROSS: My guest is journalist Edward Humes. His new book is called "Door To Door: The Magnificent, Maddening, Mysterious World Of Transportation." This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is journalist Edward Humes. His new book, "Door To Door," is about the transportation that is required, the whole transportation infrastructure, for a global economy that enables us to buy coffee beans and smart phones and socks from places around the world. So it's about everything from the huge container ships to the overnight mail trucks that deliver things to your door. So we've talked about container ships. Let's talk about the overnight mail routes that, you know, the drivers have to take 'cause you looked at that, too. And you talked to, like, the UPS people who design the most fuel-efficient, swift routes for their drivers to take. And there are some crazy algorithms involved with this.

HUMES: Oh yeah, definitely.

GROSS: Yeah. Give us an overview of what they're - what they're looking for, like what kind of routes the algorithms are trying to create.

HUMES: Well, it's all about the minutes. You know, the less time it takes to deliver something, the easier it is to achieve the holy grail of online retailing, which is to deliver the same day that something is ordered. And that's increasingly happening. And UPS is one of the many players that are involved in that. I just happened to have access to them and exploited the connection because they're engaged in delivering something like 15 million packages a day in the United States. And every extra minute it takes for them to deliver a package, you know, on the average big brown truck route, adds 12 and a half million dollars to their cost every minute. So they are really trying to make their routing work. The tactics they take, everything - you know, they're somewhat famous for this - eliminating left turns from routes because...

GROSS: Why?

HUMES: Because when you're waiting for oncoming traffic to let you turn left, the minutes are lapsing. So if you can - even if it adds a little distance to always make your turns right and go around to get to where you need to go, it ends up as a net saver for time. And this is the great irony of the convenience of the digital economy because it's making the job of these delivery companies immensely more expensive and harder. And it's adding to traffic immensely because - hey, as a consumer I'd love - I have a diabetic cat. It's not a very nice cat, and we have to get this special food for her that you can't get anywhere. It's made in St. Louis. There's nowhere around to get it. So of course you go on to Amazon and buy it there. And this was revelatory for me. It's one of the things that helped shape this book.

I clicked on it, and eight hours later, it was on my doorstep. You know, a generation ago, that would've seem like witchcraft. How does that happen? Same day delivery of something that you never went to the store to get. But as companies like UPS have to execute that and make it happen, instead of taking a truckload of goods to a store and delivering them all at once, they have to take that same truckload and go to 120 different locations, 120 different trips.

The amount of transportation involved in that is orders of magnitude greater than the old pre-Amazon model of buying things. And that, in turn, has created much more traffic congestion, which in turn adds minutes to the time it takes companies like UPS or Domino's pizza or whatever relies on the roads to close that last mile in the delivery process. It's made it increasingly difficult for them to do it and still be a sustainable, profitable enterprise. So that's only going to continue to get worse over time, until finally the whole thing isn't sustainable anymore.

GROSS: We're talking more emissions, too.

HUMES: More emissions, too, because, you know, obviously cars stuck on the road in traffic are emitting pollutants with no gain. They're just sitting there. So something like a $160 billion hit to the economy last year just in wasted fuel and wasted time from traffic congestion.

GROSS: So in studying the hidden transportation infrastructure for the global consumer economy, what surprised you most? Like, what item that you own or that you use regularly surprised you?

HUMES: Actually, it's the most mundane things that surprised me, like coffee. The interesting thing about coffee is that after it's harvested, it has a very short shelf-life until you minimally process it. You have to to clean it, wash it and remove the fruit. And coffee beans actually are big seeds. They're like nuts. They're not really beans at all. But they look like beans. Once you get it in that state, you can put them into those big burlap sacks, and they'll stay good for year. So you can put them on the literal slow boat from wherever to get them to you. And it's not until you roast the coffee that it then becomes a time-sensitive product again.

So the vast majority of coffee is shipped in that green bean state. And as coffee became more of a mass-produced commodity, the quality of the coffee became less of a concern. And its transportability became the primary concern. And this is - this is the sort of 20th-century coffee model where you would ship the bean to a big factory and grind it up and put them in a metal container that was vacuum-packed, designed for easy transport. And the problem with that is that fresh coffee gives off gas. So the transportation needs of the coffee industry led them to let all this coffee they were selling go stale before they put them in these vacuum-packed cans. Otherwise, the cans would explode.

And so for most of the 20th century, nobody really tasted fresh coffee in America because the way we transported it wouldn't allow it. And now, the coffee companies are just trying to figure out how they can alter that problem and transport fresher coffee to people. And so far there isn't really a great solution. If you don't drink your coffee a day after it's roasted, if it's being transported all these weeks in its finished state, it's going to be kind of sucky compared to the real thing.

GROSS: So really the reason why we have so much coffee in bags as opposed to in cans is 'cause of transportation.

HUMES: Indeed. The bags that they use now have the advantage of allowing the gases that the beans emit to come out through that little valve - that little plastic - if you ever wondered what that little plastic notch is for...

GROSS: I have (laughter). I have wondered that.

HUMES: ...In your bag of coffee beans, it's to let the off-gassing to occur without the bag exploding or bursting.

GROSS: Edward Humes, thank you so much for coming back to FRESH AIR.

HUMES: It's been my pleasure, Terry.

GROSS: Edward Humes is the author of the new book "Door To Door."

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

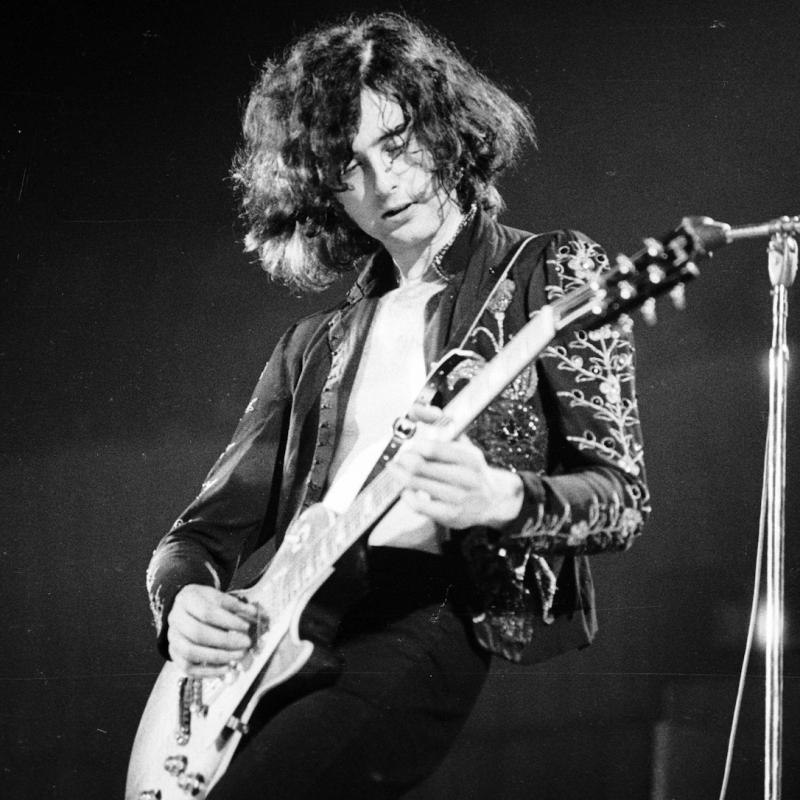

This is FRESH AIR. Our next guest, jazz guitarist Julian Lage, has had a successful two-decade career in the music business, which is kind of remarkable considering that he's only 28 years old. Lage was a child prodigy. He began playing guitar at the age of 5, appeared on stage at The Grammys at 13 and was a member of vibraphonist Gary Burton's band at 16. He was also the subject of a short documentary when he was 8, appropriately titled "Jules At Eight." At the time, Lage was playing jazz and blues with older musicians. Here's a clip of Lage speaking in that documentary.

(SOUNDBITE OF DOCUMENTARY, "JULES AT EIGHT")

JULIAN LAGE: Most people that are not musicians feel whenever somebody plays the blues they really have the blues. I mean, lots of them sound like they have been - had things in their life if they're good musicians because lots of people have good feeling for their instrument.

(MUSIC)

LAGE: A long time ago, Robert Johnson has the blues. Now, Buddy Guy plays for thousands of people. I mean, he does not have the blues. He just has very much soul into his instrument.

GROSS: That's Julian Lage when he was 8 years. He's since recorded with Gary Burton, David Grisman and Fred Hirsch and released albums under his own name. He's also recorded duets, exploring the avant-garde with guitarist Nels Cline and bluegrass and traditional music with guitarist Chris Eldridge. Lage has a new trio album called "Arclight" with bassist Scott Colley and drummer Kenny Wollesen, featuring Lage on electric guitar. He spoke with FRESH AIR producer Sam Briger. They started with a track from "Arclight" called "Fortune Teller."

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "FORTUNE TELLER")

SAM BRIGER, BYLINE: That's the tune "Fortune Teller" from the new album "Arclight" by my guest Julian Lage. Julian, welcome to FRESH AIR.

LAGE: Thank you so much, Sam, great to be here.

BRIGER: So it sounds like you're really having a lot of fun on this album and you decided to use an electric guitar for this. You actually use one of the oldest in production kinds of guitars, the Fender Telecaster and you sort of forgo the more traditional jazz guitar sound. Why did you want that very electric sound for this?

LAGE: Well, I grew up playing, you know, Stratocaster, a Paul Reed Smith, and my very first guitar when I was - before I played was a piece of plywood that was cut in the shape of a Telecaster by my father. It was a trace from a poster of Bruce Springsteen's Esquire, which is basically like a Telecaster-style guitar. The electric guitar was always so fascinating to me, and my guitar heroes played it, you know, people like Stevie Ray Vaughan or, you know, Clapton or whatnot - Muddy Waters.

BRIGER: So most of the songs on this album are originals, but you've chosen to cover a few songs from the first half of the 20th century. You've said you wanted to pick some, quote, "pre-bebop songs." Why was that era interesting to you?

LAGE: I think there's something that that era, specifically the teens and the '20s and the kind of early '30s, you know, before things got kind of codified and slick and refined. There was this thing where you kind of couldn't tell if it was country, if it was ragtime, if it was - you know, if these were the seeds of bebop, if they were showtunes. It's very hard to pin down, much like how I feel with a lot of popular music today.

BRIGER: You've said that a lot of these songs from that period have these, like, weird harmonies and, like, that they're using these cowboy chords. And you also say that these kinds of harmonies might be frowned upon today by jazz purists. But so could you demonstrate what you mean by cowboy chords and also maybe, like, how that compares to, like, say, a more accepted jazz harmony?

LAGE: Absolutely. OK, so let's see. There's a song called "Harlem Blues" that we do on the record and it's written by W.C. Handy. And the original version is more or less kind of traditional, harmonically speaking. But the arrangement we do is basically taken from Willard Robison. And Willard Robison was one of these great American composers. He wrote "Old Folks," "Lazy Bones," which was kind of a super, super hit in the sheet music world back in the day. And he did these things that I consider kind of cowboy chord moves and cowboy chords being these kind of chords (playing guitar) big, open, kind of expansive triads. But what's different and what makes them kind of weird - he would play the cowboy chord that goes in the song but he would play it, like, of off, maybe off by a half step or something, just enough of a shift that you - it kind of tugs on your ear a little bit.

So in the bridge or the B section of this - "Harlem Blues" - let's see. It goes (playing guitar). That's kind of the airy, opened version. The Willard Robison thing is (playing guitar). So it's that - this one kind of weird chord out of place that caught my attention (playing guitar). And it's - it lasts only for a second. It only stings for a minute and then you're back into the kind of tonal side of things. But I think that slippery approach to basically fundamental harmony is what is so attractive to me. And there's some other examples throughout the thing where - let's see. What's another one (playing guitar)? It goes (playing guitar). There's a certain bluntness to this kind of parallel motion of the triads.

Now, conversely, what you get maybe just, I don't know, a decade or so later - 10, 15, 20 years later - is a refined elegance that's built around two-five-ones, three-six-two-five-ones. These are all, like, cadences that kind of smooth over any harsh details, those kind of funny, like - I don't know - jabbing parts came a little bit more in the way of a passing chord. So whereas Willard Robison just very bluntly goes (playing guitar) and then back to the normal harmony, I think a lot of that later stuff had more to do with kind of interstitial stuff like (playing guitar) - do you know - where it moves a little bit and there's always a - it's like these are connecting chords. They wouldn't so boldly just throw in a weird chord.

BRIGER: (Laughter) Right.

GROSS: We're listening to the interview FRESH AIR producer Sam Briger recorded with guitarist Julian Lage. He has a new album called "Arclight." We'll hear more of the interview after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to the interview FRESH AIR producer Sam Briger recorded with guitarist Julian Lage. Lage has a new album called "Arclight."

BRIGER: One of my favorite tracks on this album is your version of the song "Nocturne." And I wanted to play a little bit of both the original version of the song from 1933 and your version. But first what can you tell us about this song and why you chose to do it?

LAGE: Well, it's a beautiful song that stood out to me because at least on the original recording - the first chorus of the song treats the - the first chord is a minor chord - this (playing guitar). It starts on this minor chord, and songs from that era, it's very hard to find things that - songs that weren't major, that weren't happy, that weren't just total dance music, you know? And I thought, wow, that is so cool to have something that starts moody. Now, the irony is - that's only the first chorus. You know, I think there's three choruses on the original version. The next two choruses, it always starts with a major chord (playing guitar). So it becomes the song that I was kind of avoiding, you know? But they gave a glimpse of it with that opening chorus. I thought that is so cool.

BRIGER: Well, let's hear just a little bit of the original version by Spike Hughes, and then we'll fade that out and hear your version from your new album "Arclight." So this is "Nocturne."

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "NOCTURNE")

BRIGER: That sounds great. So that's the original version and Julian Lage's version of the song "Nocturne." And Julian Lage is my guest. He has a new album called "Arclight." I really like - it feels like you've - you really slowed down the song a little bit and sort of made it feel kind of lazy. I don't know. It just seems like a great interpretation.

LAGE: Well, thank you. It was such a no-brainer because when you play it on the guitar it lends itself to this kind of slow hand, just easy - very kind of - I don't know how to say it. You have all the time in the world kind of style of guitar playing, which allows for a lot more inflections, like vibrato or slide-ups or other things. So, you know, if expression is the name of the game with this record, this was kind of a perfect opportunity to show that.

BRIGER: So any article about you brings up the fact that you were a child prodigy. You seem to have such tenacity as a 5-year-old to pursue this passion of yours. And it just makes me wonder what - I mean, a lot of people fall in love with the guitar. But what was it about the guitar that spoke to you so deeply?

LAGE: I think it's because my dad played it. You know, really simply put - my father picked up the guitar only a year before I did. He had played a little bit as a young man, but really it was kind of like something to do with my father. And I have three sisters and a brother, all who are older. And they had the opportunity to play guitar and do stuff, but they had other interests that took them deeply into, you know, all different worlds. So in a way it was just excuse to kind of hangout and do something my dad was interested in.

LAGE: It seems like both of your parents really helped enable your passion for guitar. Your dad is doing a lot of the heavy work there. He's driving you to all these places. He's taking you to lessons. He also says that he home late at night, and he would practice the guitar - practice what you were learning - so he would learn it well enough so you guys could play together.

LAGE: Right.

BRIGER: And essentially there's a nice balance there. Like, your parents seem very conscientious about not exploiting your talents in any way but just allowing you to develop them.

LAGE: Well, you hit the nail on the head totally. I mean, I think, my father - it's so sweet because he to me is one of the absolute greatest guitar players ever who doesn't really play guitar. And I say that because the way he thinks about it, the way he perceives it, you know, he was kind of - he's always been - and to this day really is - kind of my best coach. I'd be in a situation and my father would kind of be observing it, and then he would offer help that was so spot on but not coming from the point of view of actual guitar playing.

One of the first times I recorded, I think I was 6 or 7, and it was playing on a demo of a song that some older musicians in the Santa Rosa area, they were recording and they wanted a guitar solo. And I was friends with them and they wanted - they were just being very generous. They said come over and play. And so I go in and I overdub the solo, and I'm sitting in the room. It's the blues - whatever - something simple. And basically I'm playing way too much, you know, I just don't know when to really stop. I just keep moving my fingers and then the song stops and I keep going, and it's really awkward. And the producer is trying to be very diplomatic saying, it's good but maybe you could leave some space - could you try it again? Just try it again.

And I think my father saw me as this little boy kind of getting worn out quickly (laughter) because I was saying, OK, whatever you want, you know? He had this idea - he said, OK, can I sit next to Julian? Is that cool? And they say of course. They bring out a chair. They get him a set of headphones, and my dad sits down next to me and he says, OK, son, so when they play the song back, play whatever you want, but whenever I touch your leg, let's just take a break. Just take a break. I say, OK, whatever, you know, that sounds good. So I'm sitting there and I start playing, and then he, you know, I'd play a four-measure phrase, and then he would just rest his hand on my knee. And we would just sit there and listen to the song for little while. And then he'd take his hand off and I'd play some more, then he'd put his hand on.

We did this throughout the course of the song. And when it was done - it was perfect because he - his understanding of form and tension release was so good that he was able to kind to say this is when you're needed, this is when your not, proportionally, like, at the end, you should play more or whatever. But he didn't say any of those things to me. And it was done in such a gentle fatherly way that I was - those were the kind of lessons that kept coming up and they had a lot to do with form, tension release, narrative - that was, like, my whole upbringing 'cause I think he kind of interested me to figure out the notes. But those other things, you either kind of heard things in that way or you didn't. I'm so grateful for that.

BRIGER: It sounds like you had monthly lunches with one of your heroes, Jim Hall. Is that true?

LAGE: Yeah, that's very true.

BRIGER: What was that like?

LAGE: It was really sweet 'cause I think going into it I thought oh, my God, I'm going to go hang out with Jim. And we had been friends ever since the first time I met him when I was 11. We had been friendly and he'd call me every six months or so, and I'd get a call and I'd say, hello? It'd be unknown, blocked number, and he'd say, what's the first chord of "All The Things You Are?" And I'd say F-minor? And he'd be like, that's great. It's Jim Hall. How's it going? And I'd get these periodically and so I knew he had a sense of humor. I knew he loved to reach out. I knew he wasn't precious (ph) you know, he wasn't the almighty Oz. He was a person, you know, albeit an - the most extraordinary person.

GROSS: FRESH AIR producer Sam Briger speaking with guitarist Julian Lage. Lage has a new album called "Arclight." This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to the interview FRESH AIR producer Sam Briger recorded with guitarist Julian Lage. Lage has a new album called "Arclight."

BRIGER: Now, last year, you released this wonderful solo acoustic album called "World's Fair." And I was wondering if you would play us a song. Would you play us some of "Day And Age?"

LAGE: Oh, of course, yeah, I like playing that.

BRIGER: Thanks.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "DAY AND AGE")

BRIGER: That was great. Thank you so much for doing that.

LAGE: Thank you, Sam, of course.

BRIGER: That's Julian Lage playing his song "Day And Age" from his last year's acoustic solo album. You said that this album was a result of confronting certain fears and working around an injury. What were those issues?

LAGE: Oh, yeah, I blew my hand out. I blew out my left hand. About three or four years ago, I was playing a show in California and my left hand kind of spasmed shut, you know, basically I was gripping and - so hard evidently that my fingers just kind - they any degree of control.

BRIGER: That's scary.

LAGE: It was really scary, yeah. And it was totally the first time I'd ever had it. It wasn't - it just, you know, hit me over the head and I thought, oh my God, what have I done? And I managed to get through the show playing with basically my third - my ring finger and my pinky on the left hand. And I got off the stage and my left arm was basically, like, limp. It felt like I had short-circuited my complete - you know, the nerves on that side. So I went to the doctor's, did an MRI, checked it out. There's no nerve damage to speak of and there wasn't a definitive answer.

And then people started talking to me about it and they said, you know, it sounds a lot like focal dystonia, which is a condition that is actually a neurological condition. In a nutshell, it deals with the fact that your brain, if asked to do a certain activity so many times repeatedly - like, you know, typing, playing the piano, playing the guitar - the brain can start to almost try to become more efficient. And rather than giving you, you know, one kind of signal for your index finger another signal for your pinky, your brain will say, hey, we're - it's all going to the same place. Let's kind of combine those.

So you end up feeling like you have one big finger or you have two fingers. You don't feel the five digits of your hands. People said, you know, you did practice all those years and you did a lot of tedious stuff. You're kind of the perfect candidate for having your brain freak out. So I thought, well, that's great, you know? I didn't mean to do that. So I set about to kind of re-learn how to play the guitar in a way that was - that addressed these tendencies that got me in trouble in the first place.

BRIGER: So how do you do that? I mean, if you're - is it a lighter touch? It doesn't sound like it's muscular, though, right, so it's neurological.

LAGE: Well, that's just it. It's not even - and you hit the nail on the head - my first thing was, well, I'm playing too hard. I'll play lighter. And that would cause more trouble. Then I'd think, well, how is that possible? You know, in all the years of practicing stuff what I hadn't - you know, I think the way I look at it is you have to always kind of re-inspect your beliefs about the guitar. And you have to say, does this still hold true given what I know now, you know? And I feel like those are updates that musicians do all the time. And the one - the biggest thing that I never really unpacked was my conception of strength.

You know, when I was 5 years old the guitar was bigger than me and I had this conception that in order to play the guitar I had to throw myself into it and squeeze in a way that made kind of an adult sound, which meant that I, you know, I was scrappy. I squeezed with my left hand, I squeezed with my right hand - anything so that I, one, made a sound that sounded official, and two, I didn't drop the guitar, you know? And once I started looking, then I'd say, OK, well, now I'm quite a bit taller and I am stronger. Am I letting any of those resources actually work in my favor or am I still gripping as if the guitars is three times my size, you know? And so it unlocked this whole thing where I practiced a lot of - a lot of my practice in recovery from that injury, at least the beginning, was - had nothing to do with playing and everything to do with balancing the guitar. You know, say, OK, I'm going to sit here. I'm going to put the guitar on my lap. I'm going to see how far I can tilt until it falls.

And as soon as it would start to move out of position I would tense up and my arm would feel weird. I hadn't played a note, you know? And so then I'd let it fall a little further and I'd always catch it. And then I'd, you know, do it near a couch. I'd let it fall on the couch and just letting go of the guitar so that I could ironically hold it again was kind of step one. Step two was re-evaluating some very basic technical things. There were two teachers who kind of saved my life - guitar teachers. One is a brilliant flamenco guitarist named Juanito Pascual and the other is Jerald Harscher, both classical and flamenco players who had experience with this and then devoted their lives to finding more efficient techniques. The biggest one was - I don't know if this will be of any interest but it's - as a kid I was told that your left hand - you have to touch the guitar like you're kind of holding an orange.

So you make, like, a C shape and then you apply pressure. And what both these teachers taught me to do was to - they basically taught me how the hand actually works and how to let it almost collapse into the guitar. So my technique now is a lot more like smushing my hand into the neck rather than being like a jet fighter pilot whose, like, accurately shooting something at a target, you know? I gave up on precision in a big way and ironically it gave me a lot more precision.

BRIGER: Well, Julian Lage, thanks so much for being with us.

LAGE: Thank you, Sam, it's been such a treat.

GROSS: Guitarist Julian Lage spoke with FRESH AIR producer Sam Briger. Lage has a new trio album called "Arclight."

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.