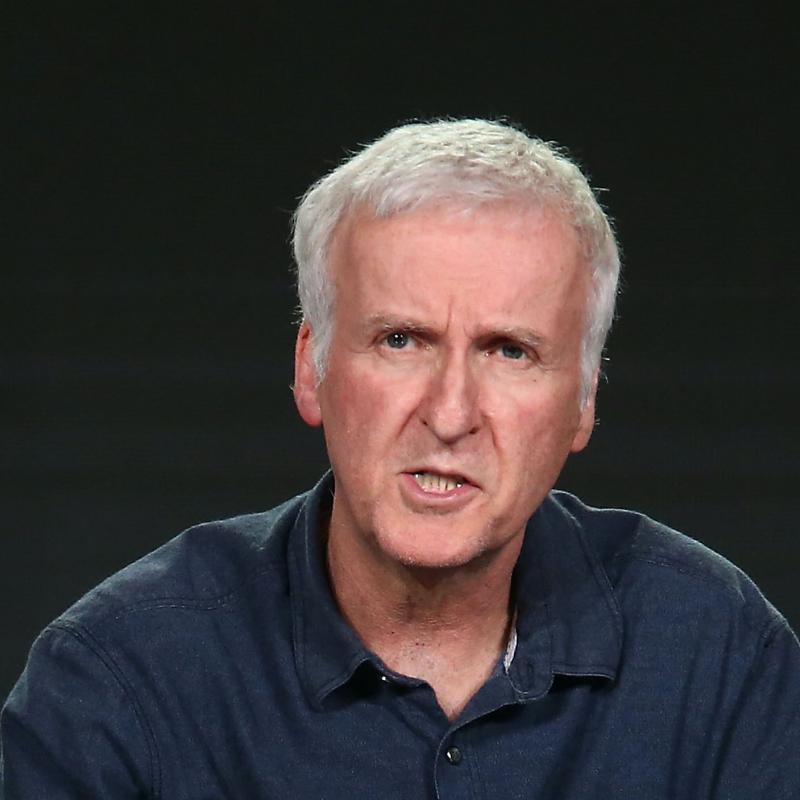

James Cameron's Craft: Blockbuster Special Effects.

You might define the films of James Cameron by listing two characteristics: state-of-the-art special effects and huge box-office receipts. Cameron discusses the special effects in his films Titanic, The Terminator and Avatar — and explains how he came up with his innovative filming techniques.

This interview originally aired Feb. 18, 2010

Other segments from the episode on April 23, 2010

Transcript

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20100423

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

James Cameron's Craft: Blockbuster Special Effects

DAVE DAVIES, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies, sitting in for Terry Gross. Film director

James Cameron has created the two highest-grossing movies of all time, the 1997

film "Titanic," and of course his latest, "Avatar," which is now out on DVD.

"Avatar," which has made over $2.7 billion, also received Oscar nominations,

including Best Picture and Best Director.

Cameron first came up with the idea for "Avatar" 15 years ago, but he shelved

the project, feeling that the technology didn't exist to make the film. In the

intervening years, Cameron helped develop a new digital 3-D camera system,

which he used to film many underwater documentaries, as well as "Avatar."

Now, most of the major animation studios and a handful of A-list directors are

investing heavily in 3-D. They hail it as the next revolution in film. Terry

spoke with James Cameron in February.

"Avatar" follows Jake Sully, a former Marine confined to a wheelchair, who

along with other military contractors is hired by a corporation to become part

of a mission on the planet Pandora. The company's goal is to extract a precious

ore on Pandora, but the Na'vi tribe, who live on Pandora, are getting in the

way. Jake becomes part of a scientific team that's tasked to interact with the

natives.

He becomes an avatar in the form of a Na'vi. He's adopted by the group and

begins to fall in love with his guide, Neytiri. As he becomes more and more

involved in life on Pandora, he begins to question his mission.

Here's a scene from early in the film. Jake is recording his first video log.

He talks about starting to learn the Na'vi ways.

(Soundbite of film, "Avatar")

Mr. SAM WORTHINGTON (Actor): (As Jake Sully) This is a video log, 12 times 21,

32. Do I have to do this now? I really need to get some rest.

Unidentified Woman #1 (Actor): (As character) No, now, when it's fresh.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. WORTHINGTON: (As Sully) Okay, location, shack, and the days are starting to

blur together. The language is a pain, but you know, I figure it's like field-

stripping a weapon. It's repetition, repetition. Na'vi.

Unidentified Woman #2 (Actor): (As character) Na'vi.

Mr. WORTHINGTON: (As Sully) Na'vi.

Unidentified Woman #2: (As character) (Speaking foreign language).

Mr. WORTHINGTON: (As Sully) Neytiri calls me scoun(ph). It means moron.

TERRY GROSS, host:

Jim Cameron, welcome to FRESH AIR. Can I ask you to give us an example of a

shot or two, or a scene, that epitomizes for you what you can do with 3-D that

you couldn't do in a regular film?

Mr. JAMES CAMERON (Filmmaker, "Avatar"): Well, I think it's sometimes as simple

as, you know, a shot in a snowstorm would feel so much more tactile to the

viewer. You'd actually feel like the snowflakes were falling on you and around

you, you know, that sort of thing, any time that the medium of the air between

you and the subject can be filled with something.

So we did a lot of stuff in "Avatar" with, you know, floating wood sprites and

little bits of stuff floating in the sunlight and so on, and rain and

foreground leaves and things like that. It's all a way of wrapping the audience

in the experience of the movie.

GROSS: And there's even a shot - and I think this looked deeper because of the

3-D, but you tell me - there's a shot in which the spaceship that's

transporting the people to Pandora, it's a shot of, like, a long, narrow bench,

basically, of seats, like a row of seats that the guys are sitting on. And I

think it looked particularly long because of the 3-D, or is that just me?

Mr. CAMERON: No, I think you're right. I think it's an enhanced sense of depth.

We get depth queuing in flat images all the time. We understand perspective,

you know, linear perspective, aerial perspective. When we see a human figure,

and that figure's very tiny, we don't - our brain immediately says that's not a

tiny guy, an inch tall, that's somebody very far away.

So all those depth queues are always there. When you add what 3-D does, 3-D

gives you parallax information. It actually gives you the difference between

what the left eye sees and what the right eye sees, and that creates even more

depth information.

So now all these different depth queues have to be correlated in the brain in

the space of a few microseconds when you first see the image. And I would

submit, although I haven't seen data on this, that the brain is more active.

The brain is more engaged in the processing of the images.

GROSS: So do you see in 3-D as you're shooting?

Mr. CAMERON: Well, I mean, we all see in 3-D all the time.

GROSS: But not through a lens.

Mr. CAMERON: Well, no, I mean, I can. I have a 3-D viewing station nearby, but

I typically don't use it because I've done - I've shot so much 3-D, I kind of

know what it's going to look like. So I don't slow down to check it. But you

know, I have somebody watching, and if there's something that I'm not aware of,

they'll let me know.

GROSS: Didn't you help develop, like, a special, new virtual camera?

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah, but that's a whole different deal. That has nothing...

GROSS: What is it?

Mr. CAMERON: That has nothing to do with 3-D. The virtual camera was a way of

interfacing with a CG world so that I could view my actors as their characters

when we were doing performance capture. So imagine, here's Zoe Saldana or Sam

Worthington in our capture space, which we called the volume, and when you look

at them, they're wearing kind of a black outfit, which is their capture suit.

But what I look at, and what I see in my virtual camera monitor is an image of

them as a 10-foot-tall, blue, alien creature with a tail.

GROSS: Wow, that's...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: And it's in real time.

GROSS: That's kind of amazing.

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah, it's simultaneous.

GROSS: So there's, like, a computer, a CG computer in the camera that

transforms the image?

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah, more or less. The camera really is just a monitor and a set

of tracking markers, and it connects to a couple of computers, actually. The

first one takes in that tracking data and figures out where the camera is in

space relative to the actors. And then the second computer takes that

information about the characters and where they are and turns them - or the

actors and where they are and turns them into their characters and supplies the

setting.

So I would see Zoe and Sam as Neytiri and Jake in the jungle of Pandora, for

example, you know, fully lit image of the Pandoran rainforest. You know, it's

not the same as the final image of the movie in the sense that it's a much

lower resolution so it can render in real time.

GROSS: Now, you had to make up a language, also, I think with the help of a

linguist.

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah.

GROSS: What were you looking for in the language, and how do you put together a

kind of grammatically coherent language?

Mr. CAMERON: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Well, that's where the linguist, Dr. Paul Frommer,

came in. And he was the head of the linguistics department at USC at the time,

and he did more than help. He actually created the language. Or more properly,

he created the translations of the lines that we needed for the script. I don't

think - he didn't create, like, a full language with a vocabulary of 20,000

words, but I think we now have a vocabulary of about 1,200 or 1,300 words.

And I actually had him on set with me so that if the actors wanted to

improvise, they could go over to him, and say how would I saw this, how would I

say that? Sometimes he had to create words right on the spot, but they had to

be words that were consistent with the kind of sound system that we were using

for the language.

And I guess I sort of set it in motion when I created character names and place

names and based them on some, you know, kind of Polynesian sounds and some

Indonesian sounds. And he riffed on that, and he brought in some African sounds

that were ejective consonants and things like that, kind of clicks and pops,

and he sprinkled those in. And he came up with a syntax and a typical sentence

structure, which I think has the verb at the end, kind of in the German

sentence structure, you know, I to the store go. It's noun, object, verb. So I

think that's how Na'vi is structured.

So it follows linguistic rules, and that's why it sounds correct. And all the

actors had to adhere to a standard of pronunciation so that it didn't sound

like everybody was making up their own gobbledygook, which I think over a two-

and-a-half-hour movie you would have felt you were being had if we had done it

that way.

GROSS: So can you speak to me in the Na'vi language?

Mr. CAMERON: You know, I mean, I can only say lines that are in the film.

GROSS: Yeah, yeah, that's fine.

Mr. CAMERON: I can say, well: (Speaking foreign language). That means I see

you, my sister. No, I see you my brother.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: (Speaking foreign language) is I see you, my sister. Or (Speaking

foreign language) means I was going to kill him, but there was a sign from

Awha(ph).

GROSS: "Avatar" combines a lot of different movie genres in its own way.

There's aspects of the Vietnam War movie, aspects of the Iraq War movie because

a lot of people think Iraq War is about oil, and...

Mr. CAMERON: Sure.

GROSS: ...the battle in your movie is about some kind of ore, some kind of

mineral that's very valuable.

This parallels to the Westerns, where, you know, like the white people come and

conquer the indigenous people. And there's parallels to, like, creature films

like "King Kong" where he battles other prehistoric creatures and, you know,

"Rodan vs. Godzilla" kind of film.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Were you thinking of all those genres?

Mr. CAMERON: Now you're getting out on a - you're getting out on a limb now.

GROSS: No, I don't know.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: Well, you know, look, the Vietnam stuff and the Iraq stuff is

there by design. And the references to the colonial period are there by design,

the way in which, you know, European civilization flowed outward and sort of,

you know, took over and displaced the indigenous people in North America, South

America, Australia - pretty much everywhere they went, you know.

And, you know, so I think it's at a very, very high level, at a general, at a

very generalized level, it's saying our attitude about indigenous people and

our sort of entitlement to what is rightfully theirs but our sense of

entitlement is the same sense of entitlement that causes us to bulldoze a

forest and not blink an eye.

You know, it's a - it's just human nature that if we can take it, we will. And

sometimes we do it in a very, you know, just naked and imperialistic way, and

other times we do it in, you know, very sophisticated ways with lots of

rationalization, but it's basically the same thing. It's a sense of

entitlement. And we can't just go on in this kind of unsustainable way, just

taking what we want and not giving back.

GROSS: The main character, the main male character in your movie is a Marine

who lost the use of his legs in war, but by becoming an avatar, he gets to live

a parallel life...

Mr. CAMERON: Right.

GROSS: ...through his avatar. And his avatar has these incredible physical

adventures, beautiful physical adventures.

Mr. CAMERON: Right.

GROSS: And I read that your brother is, or was, a Marine.

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah, well, you're never an ex-Marine. You know, once you're a

Marine...

GROSS: Right, right.

Mr. CAMERON: ...you're always a Marine, even if you're out of the Marine Corps.

You know, he was in - he fought in Desert Storm in '91. And you know, he's

regaled me with tales of the Marine Corps. And you know, I have a number of

guys that work for me that were, you know, his squad mates or other Marines

that he met, you know, in his travels.

And I have a great deal of respect for these guys. I really personally believe

in their world view, which is one of a sense of being able to overcome any

obstacle. They have a great sense of duty. They want to have a mission.

And I thought: How cool would it be to have a main character in a science

fiction movie who was a Marine? And so I just played that idea out. You know,

that was on my mind. You know, Desert Storm was in '91. I was writing this in

'95.

And I think that's - and one thing that has struck me recently because there's

been so much chat, kind of, around this movie, is that there's been almost zero

dialogue about the fact that you have a major action movie where the main

character is disabled, which I think is actually unprecedented. And yet

nobody's said anything about that. I think it's kind of strange, to tell you

the truth.

DAVIES: Director James Cameron, speaking with Terry Gross. More after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

DAVIES: Let's get back to Terry's interview with director James Cameron,

recorded in February. His film "Avatar" is now out on DVD.

GROSS: You are now probably most famous for your biggest films, "Titanic" and

"Avatar," both of which have a lot of special effects and feats in them. But

you started off helping to make Roger Corman's films.

Mr. CAMERON: Mm-hmm. Right.

GROSS: Movies like "Battle Beyond the Stars," "Galaxy of Terror." And Corman is

famous for, in his early career, making these like, real low budget, quickie...

Mr. CAMERON: Cheap.

GROSS: Yeah. Yeah, you know, action films and...

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah. He's famous for being cheap.

GROSS: Yeah. So, what did you learn from the real cheap side of special

effects...

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: ...that you later applied to the real expensive side of special effects?

Mr. CAMERON: It's a funny question because I was just talking to Roger last

night, and I haven't seen him in years, but we ran into each other, and we were

joking about the fact that he's made - probably all of his movies combined

would not have cost as much as "Avatar." And he's made, you know, 100 films.

But, you know, we were having a good laugh about that. But yeah, there are

lessons that one learns in those early kind of guerrilla filmmaking days that

stay with you the whole time.

And, you know, and what you learn in those early films is just that your will

is the only thing that makes the difference in getting the job done - one's

will. And it teaches you to improvise and in a funny way to never lose hope,

because you're making a movie, and the movie can be what you want it to be.

It's not in control of you. You're in control of it, you know, so there are a

lot of lessons that are more really character lessons.

GROSS: So can you share your favorite cheap special effect that you were

involved with from a Corman film?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: Well, they were all cheap. You know, I mean we used to love - we

actually were fairly sophisticated even for that time. We were doing motion

control and fairly complicated optical special effects and so on for Roger.

But, of course, the ones we liked the best were the biggest cheats, where we'd

glue a model to a piece of glass and stick it in the foreground and pretend it

was far, you know, far away and really big and have all the actors turn away

from the camera and point at it even though it was sitting right in front of

the camera. And it actually created a compelling illusion, you know, foreground

miniature. It was a lot of fun. And it's the ones where you really think you're

get, you know, you're pulling something over on the audience that were the most

fun.

GROSS: Now, you know, in "Titanic" there were so many like, water-rushing-in

kind of effects when the boat was â when the ship was sinking.

Mr. CAMERON: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And I know you grew up not far from Niagara Falls. Is that right?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: Right. Yeah.

GROSS: So is it stretching too much to think that the power of the water of

Niagara Falls had some kind of influence on you?

Mr. CAMERON: Well, you know, I mean I grew up within the sound of Niagara

Falls. I lived, you know, with that constant rumble in the background. So I

certainly always had a respect for the power and the force of water.

And then in the filmmaking, starting with "The Abyss," I saw how, you know, you

can dump a dump tank with 10,000 gallons in it and have it destroy your set, I

mean literally rip it apart. And so, over time, I've learned to really, really

respect that force of water from an engineering standpoint.

And I'm very rigorous when I work with water that my, that, you know, my

special effects guys and my set construction people, so on, really understand

what they're dealing with. Because generally speaking, they underestimate the

force and energy of water by a factor of 10.

GROSS: When you say that this thing of water ripped apart your set, you mean

accidentally, right?

Mr. CAMERON: Accidentally, yeah.

GROSS: What happened?

Mr. CAMERON: Well, it blew the wall right out. You know, we were doing a

flooding scene, and it hadn't been properly strong-backed. And, you know, no

one was hurt but, you know, it really makes you realize what you're dealing

with.

So on "Titanic" we had a lot of water stunts. And, you know, I would, you know,

constantly, you know, walk the set, look at how it was rigged and so on, and

I'd want to see the engineering. I'd want to see the numbers. I'd want to see

how they had calculated everything to make sure that there was a safety margin.

GROSS: Okay. James Cameron, years before Governor Schwarzenegger was governor,

he was...

Mr. CAMERON: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...your cyborg in "Terminator."

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: So I'm sure you've told this many times but...

Mr. CAMERON: I'm not sure who was working for who at that time.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: I'm sure you've told the story many times but tell us how and why you

cast him.

Mr. CAMERON: Well, you know, I actually had this kind of flash that Arnold had

this amazing face. I wasn't - I mean his physique was fine, made sense that we

could hide this kind of infernal machine inside that, you know, inside his size

of his physique, but it was really his face that was interesting to me.

And, you know, someone suggested that he play the character played by Michael

Biehn, and that didn't make much sense to me. But I wound up going to lunch

with him, and we had this great time talking about the movie and just life in

general. I found him to be incredibly charming and intelligent, and that was

really the beginning of a friendship.

And so I went back to the executive producer of the film and said, you know,

he's not going to work as Reese, but he'd make a great terminator. And we

offered him the part that day and that's how the movie got made.

GROSS: Now, Charlton Heston was in one of your movies "True Lies," which...

Mr. CAMERON: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...starred a more charming version of Arnold Schwarzenegger. He's like

a...

Mr. CAMERON: Oh sure.

GROSS: ...a secret spy in it, and even his wife doesn't know he's a spy. And

he's very charming and elegant in that side of his life.

Mr. CAMERON: Right. Right.

GROSS: And very tough and brutal on the other side of his life. Charlton Heston

has a small part in it.

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah.

GROSS: And it must've been interesting to direct him. I mean, he was, among

other things, Moses in the movies. I'm sure your politics are very different

from him.

Mr. CAMERON: Oh yeah, very different. But I found him charming and really

humble before the craft of acting in the old-school way. He came in, he said,

just call me Chuck. Don't let the fact that I'm an icon, you know, affect you.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: And...

GROSS: He said, modestly.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: He said modestly. And then he sat in a chair, and he never left

the set all day long. He came in for off-camera, you know, to do his side of

the scene for off-camera, which, you know, certainly a star of his stature

wouldn't need to do. And he never left the set. He just sat there and read.

And you could just see that it was a life of - there were patterns formed by a

life of dedication to the craft, and I really respected that. And, you know, I

felt I had to really be on my game that day and be 100 percent professional as

a director because, you know, he came from the studio system where, you know,

you shot X number of pages a day, boom, boom, boom, and everybody knew their

tasks and, you know, it was a lot of fun working with him.

GROSS: Now, you didn't expect to go into movies. So what was your break that

led you through the door?

Mr. CAMERON: Well, I think you make your own luck, you know, and it wasn't

really a break. I had started â I had sort of quit my job. I was working as a

truck driver. I quit my job. I started making little films, you know, used up

all my savings. And somehow a little effects film that I had made got the

attention of somebody who was working for Corman on "Battle Beyond the Stars."

And I wound up getting an interview and coming into the model department and

sort of clawing my way up through the system pretty rapidly, which you could do

in that kind of environment because it was so kind of ad hoc, and nobody really

knew what they were doing anyway.

So, you know, I mean you get the door open a crack, and then you, you know, you

just keep wedging your way through the door. That's how you work it.

GROSS: Thank you so much for talking with us. It's really been fun and

interesting. Thank you.

Mr. CAMERON: Thanks.

DAVIES: James Cameron, speaking with Terry Gross, recorded in February. His

film "Avatar" is now out on DVD. I'm Dave Davies, and this is FRESH AIR.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

126191838

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20100423

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Persian Cats' Just Want To Rock 'N' Roll ... In Iran

(Soundbite of music)

DAVE DAVIES, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies in for Terry Gross.

There's an acclaimed new music film from Iran now in theatres and available

through IFC Video On Demand. It's called "No One Knows About Persian Cats," and

has been admired abroad. It won the Special Jury Prize at last year's Cannes

Film Festival, even as it was being suppressed back in Iran. The movie was

directed by Bahman Ghobadi, an Iranian Kurd who's earlier films include, "A

Time for Drunken Horses" and "Marooned in Iraq."

Our critic at large John Powers says the film is a reminder for Westerners of

the liberating potential of pop music.

JOHN POWERS: When I was growing up, it was an article of faith that rock 'n'

roll could change the world. These days that faith has waned. You see, rather

than overturning mainstream culture, rock has turned into it. The Who didn't

actually die before they got old, they played halftime at the Super Bowl.

But there are places in the world where pop music still does carry a

transformative charge. One of them is the Islamic Republic of Iran, whose

leaders are still busy clamping down on the millions who believe that the

ruling government stole last summer's election.

The state's attempt to squash free expression lies at the heart of "No One

Knows About Persian Cats," a jagged, energetic, touching new movie by Bahman

Ghobadi. Shot without permission on a small digital camera, this thinly

fictionalized portrait of Tehran's underground music scene uses real musicians

to re-enact the conflict between indie rockers who just want to make music and

authorities who find the Great Satan's horns in every riff and backbeat.

The movie centers on two mild-tempered musicians: the bearded Ashkan and the

scarfed Negar, who've just gotten out of prison for their musical crimes. He

and she aren't radicals who are looking to rock the Casbah, even if the Casbah

was in Iran, not Algeria. No, they just want to find some musicians for their

band - it's called Take It Easy Hospital - and to get documents so they can

play abroad. To do this, they enlist the help of their wheeler-dealer friend

Nadar(ph), an exuberant DVD bootlegger.

The three spend the movie zooting around the city, often traveling in darkness

and dipping into basement hidey-holes. Along the way they encounter music

producers, traffickers in illegal passports, bullying magistrates and above

all, other musicians. There's the handsome singer who teaches refugee kids from

Iraq and Afghanistan. There's the metal band that practices among cows in a

barn. And there's the terrific rap group Hichkas, who insist that their songs

can only have meaning when played for people in Tehran.

As we listen to the various bands, Ghobadi offers us video montages of that

city - shades of early '80s MTV. They give us a feel for the texture of a

sprawling metropolis defined by wealth and poverty, exuberance and repression.

None of these songs are directly political and it startling to realize that the

mullahs could actually feel threatened by glum song like this one. "Human

Jungle" by Take it Easy Hospital.

(Soundbite of song, "Human Jungle")

TAKE IT EASY HOSPITAL (Band): (Singing) I've been there alone. I've been there

with you. Believe me out there, there's a jungle. Together or alone. Together

or alone.

People are looking for a way to survive. But we are just looking for a shortcut

together or alone. Together or alone. Nobody knows me. Nobody feels me. Nobody

knows me. Nobody needs me. Human jungle rules our lives...

POWERS: The great Polish philosopher Leszek Kolakowski used to say that one of

the most crushing flaws of communism was its totalizing vision. It had opinions

about everything - art and science and what you ought to be thinking. The same

holds true for a theocracy like Iran, where the state weighs in on how people

dress, what they do with their pets - Persian cats, for example, can't be taken

outside - and what culture they're allowed to enjoy: a bullying well documented

in Azar Nafisi's superb bestseller "Reading Lolita in Tehran" and in Jafar

Panahi's wonderful movie "Offside," about teenage girls who disguise themselves

as boys to attend soccer matches because women aren't allowed to attend. It's

worth noting, by the way, that Panahi - the key Iranian filmmaker of the last

decade - is now in prison for protesting last summer's election.

Now, you can understand why the mullahs hate rock music, which doesn't merely

possess an unruly energy. It enters people's heads as the siren song of the

West. They're well aware that rock 'n' roll became one big way that Soviet and

Eastern European dissidents showed their rejection of communism. It was no mere

coincidence, after all, that Vaclav Havel, the king of Czechoslovakia's Velvet

Revolution, was a huge fan of The Velvet Underground. That said, the Iranian

authorities are stuck with the same paradox that boomeranged on the communists:

When you crack down on rock music, you only make it a more powerful and

alluring metaphor for freedom.

That's precisely what we see in "No One Knows About Persian Cats". Negar and

Ashkan and their pals aren't radicals. They're passionate young people who just

want to play the alienated music they love. But because the authorities won't

let them, they believe, as one says, you can't do anything here. And it's this

angry disillusionment - far more than any rock song - that explains why

hundreds of thousands of young people have taken to the streets, and why the

Iranian theocrats should be worried that the times, they are a-changin'.

DAVIES: John Powers is film critic for Vogue and his reviews and columns appear

on Vogue.com.

Coming up, we remember a pioneering film editor Dede Allen who died Saturday at

the age of 86.

This is FRESH AIR.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

126145787

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20100423

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Remembering Pioneering Film Editor Dede Allen

DAVE DAVIES, host:

We're going to remember Dede Allen, a master film editor who died last Saturday

in Los Angeles. She was 86 years old. One of her achievements was editing the

classic 1961 movie "The Hustler." It starred Jackie Gleeson as Minnesota Fats

and Paul Newman as the aggressive young pool shark Fast Eddie Felson.

(Soundbite of movie, "The Hustler")

(Soundbite of pool balls)

Mr. PAUL NEWMAN (Actor): (as Fast Eddie) I dreamed about this game, fat man.

And I dreamed about this game every night on the road. Five ball.

(Soundbite of pool balls)

Mr. NEWMAN: (as Fast Eddie) You know, this is my table, man. I own it.

(Soundbite of pool balls)

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. NEWMAN: (as Fast Eddie) Thirteen ball.

(Soundbite of pool balls)

Mr. NEWMAN: (as Fast Eddie) Seven ball.

(Soundbite of pool balls)

Mr. NEWMAN: (as Fast Eddie) Four ball.

(Soundbite of pool balls)

Unidentified Man (Actor): (as character) Game.

(Soundbite of pool balls)

Mr. NEWMAN: (as Fast Eddie) Eleven ball.

(Soundbite of pool balls)

Mr. NEWMAN: (as Fast Eddie) Rack 'em.

(Soundbite of applause)

Mr. NEWMAN: (as Fast Eddie) Ten ball in the corner.

(Soundbite of pool balls)

Mr. NEWMAN: (as Fast Eddie) Ten ball in the corner pocket.

(Soundbite of pool balls)

(Soundbite of applause)

Unidentified Man (Actor): (as character) Game.

DAVIES: In 1999, Dede Allen became the first film editor to receive a Career

Achievement Award from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. She's credited

with editing or co-editing 20 major films over a 40-year period, including "Dog

Day Afternoon," "Serpico," "Night Moves," "The Missouri Breaks," "Reds," "The

Breakfast Club," "The Addams Family" and "The Wonder Boys."

Editing is essential in shaping the narrative and rhythm of a film, yet we

often aren't conscious of it. But in Arthur Penn's 1967 film "Bonnie and

Clyde," the editing of the final shootout was clearly remarkable. It was one of

the most violent death scenes in cinematic history up to that point. As Bonnie

Parker and Clyde Barrow were hit with dozens of bullets, we see their bodies

twitch and jump with the impact of each hit. And adding to the impact of the

scene were the rapid edits that conveyed the fury of the bullets and showed the

action at varying speeds.

(Soundbite of movie, "Bonnie and Clyde")

(Soundbite of gunfire)

DAVIES: Terry Gross interviewed Dede Allen in 2000. They began by talking about

that shootout scene in "Bonnie and Clyde."

TERRY GROSS: You know what's always interested me about that scene, that it's

really so little blood for so many bullet holes. It's almost as if there's a

double standard in what violence is acceptable, that the bullets were okay but

not the blood.

Ms. DEDE ALLEN (Film Editor): Well, an interesting thing, which is a parallel

thing to this, is when we saw it, it was at a preview and Arthur almost died

because everything was so bloody and so red. And I spent 11 more days at

Technicolor to get the tone that Arthur wanted. I mean he was just distraught.

It was a great preview. You know, it saved our lives that preview, but the

color was pretty heavy and dense and the blood was very, very dark.

And I don't know how that quite relates to the bullets but certainly, I don't

think Arthur was ever interested in having violent blood spurting out unless it

was a real reason for it because basically this was a film that he made after

the Kennedy assassination, and I've always felt that that was â that last scene

was a kind of a symbolic scene about the violence in America which, of course,

still exists.

GROSS: When you were first learning how to edit film were there certain rules

that you were told were basically unbreakable that you've subsequently broken?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Ms. ALLEN: Oh yes.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Ms. ALLEN: I remember one man, a very, very generous man who was doing Ann

Miller pictures and he took me in and said I want to teach you something. He

said you always start with a long shot, then you move in to an over shoulder or

a group shot. And he said and you never change that order. Of course, when I

started cutting in the years in New York before I could get features I was

working in a - what was called a spot house and I was doing industrials and

things. And somehow or other I was breaking that rule constantly.

I was doing medical films where, you know, I just didn't seem to think about

that that way. When I got a chance to cut for Bob Wise I was terrified. He was

after all, Orson Welles' editor and, you know, and I was very impressed. This

was the first picture he also was in charge of producing. Harry Belafonte was

producing a picture called "Odds Against Tomorrow," 1959, and I was by then 34

years old and I had been â I had started when I was 18, so that was a long

route to get there.

But the first Saturday that I ever showed Bob Wise my first scene it was a

scene up on Riverside Drive in a clunky apartment where Ed Begley and Robert

Ryan first meet with Harry Belafonte and Robert Ryan plays a very racist bank

robber. And I worked that scene over and over and over again. And in those days

you had hot splices, meaning big foot splices where if you lost a frame you had

to slug it in black.

And so the first sequence that I showed him it had what I used to call little

blackies in them. You know, little black slugs in them. And he looked at the

scene and he punch me on the arm and says good girl. I like to see you've been

working with that. Never be afraid. I said, oh I was so afraid all my mistakes

would show. He says no. He says you've been working the scene. It wasn't like a

time now where it would be Avid or something where can do it any one of a dozen

ways and nobody sees your mistakes. He was just so encouraging. I mean I

couldn't have had a better mentor as my first big feature.

GROSS: Let me ask you about the film "The Hustler," one of the early films you

edited. This is the 1961 classic about pool hustlers starring Paul Newman and

George C. Scott.

Ms. ALLEN: Right.

GROSS: And Jackie Gleeson. It was directed by Robert Rossen. In the pool scenes

there's a real great rhythm between the pool shots, the view of the table and

the cutaways to the reactions of the players and the spectators. And in some

scenes the pace seems to just escalate as the game goes on and tension

increases. Can you describe your approach to editing those pool sequences

through the film?

Ms. ALLEN: Yes. Actually the pool sequences were the first things that were

shot. We were in Ames Pool Hall for a long time and I was back in my cutting

room cutting it. And when we shot what became montages and even the ones that

were montages as the pace increased in that whole sequence at the beginning of

the first big game that Minnesota Fats wins, it was long but it played.

This is the point I think I'm trying to make, it played. It played long. Once

it was say a full reel and I got it down to then a half a reel and then, you

know, this is for each montage. Some of the montages were faster. But if a

scene played Rossen would tell me well it's kind of a he said don't piss in the

mustard. It's kind of a dirty expression.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Ms. ALLEN: I don't know it you can use that. Don't improve it into a disaster.

GROSS: So you like to be at the rehearsals if possible. You like to be on the

set. You like to see the dailies. Do you ever worry that that will influence

your decision? That when you're actually editing a movie that a scene might

look different than your memory of it or then the way it played on a set, and

that you'll be kind of too influenced by the way it played on a set as opposed

to...

Ms. ALLEN: Well, that's a good question. That's a very good question because

actually I don't like to be on the set. I don't want to know who's fighting

with who. I don't want to know any of that. That doesn't interest me in any

way. I'm only on the set when I'm called on the set.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Ms. ALLEN: Otherwise I don't really go on the set. I never go on the set

because I like to look at the film and for me it's fresh.

GROSS: Right.

Ms. ALLEN: And I don't have to know any of the baggage that goes with making

it.

GROSS: What should a good editor do to watch out for an actor?

Ms. ALLEN: Well, you just don't put anything â you never make an actor look,

for instance, if a woman is going up a staircase and there's a camera following

her and it's someone who's being photographed, even if they have a very slender

figure, sometimes they could look a little wobbly in the rear end. You would

never put a shot like that. And I've sometimes seen things like that, where

actors weren't protected as much as they could or an actor has a bad take and

you - or they take a breath or they take that pause that you know is a

preparation, and I've sometimes seen those left in films, and thatâs someone

who just didnât know that they could get rid of that and cover it and not show

where an actor basically paused because they were doing a prep. You have to

know when they're really into the character and when they're not. Itâs a matter

of knowing good acting, I guess.

GROSS: Mm-hmm. Youâve seen the technology of film editing change a lot since

the 1940s, when you started as an apprentice. Tell us how you made an edit when

you first started and how you make them now, digitally?

Ms. ALLEN: Well, when you first start you make an edit on film, you cut it on a

splicer. And the splices have all changed too, because they used to be - or you

do it with a scissor. I beg your pardon. I haven't gone back far enough.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Ms. ALLEN: You do it with a scissor and you would lose one side of the frame.

You would lose a frame between each cut and so you had to put â there are some

even - I think in 16 mil â when you lose two frames. I can't quite remember,

but that's what I meant when I was talking about the Bob Wise, the first scene

I ever cut.

GROSS: Right.

Ms. ALLEN: If you lost the frame, you had to slug it and you would slug it in

black because that shows better than white. You wouldnât slug it in white

because that would flash bright. So you would see the thing shatter with these

little black things going through. I remember at Columbia, where I first

started, I never got into the picture department there, but I remember before

preview there would be these â I would go up sometimes and be called in to help

clean the film. They would clean the film within an inch of its life and

replace any slug that was in it for the preview, and you would have your hand

in a big double tin of carbon tet, which became very dangerous later. And you

would squeegee it through various solvents very, very slowly to clean it up for

the picture.

GROSS: Carbon tet is like a dry cleaning fluid.

Ms. ALLEN: Yeah. Itâs something used to be used for cleaning film, but itâs an

noxious one. I mean itâs not, you know, you can get very sick from it.

GROSS: Right.

Ms. ALLEN: But we didnât know that in those days.

GROSS: And now youâre editing digitally.

Ms. ALLEN: Now I'm editing digitally. Then there was the period when you had

tape, of course. You know, you spliced it and you had - then you had the period

of the Carlos Rivas, which is a straight splicer, where you only have to put

one sprocket. And then Walter Murch developed one where you only had to put a

half a sprocket, an little tiny thing where you never saw the tape. I mean each

generation contributes. Itâs wonderful.

GROSS: Did you ever find yourself resisting change and preferring it the old

way? Or did you go along with all the changes and welcome them?

Ms. ALLEN: You can't work in this industry if you resist change. I happen to

love equipment. I mean, you know, when I lived with my grandparents the last

three years of high school, I would fix the pluming and stuff like that. My

grandfather was a surgeon. He wouldnât touch anything like that. So I was

always - had fun with my â mechanically - so I had no troubles with Moviolas

and things like that, because mechanically I kind of liked them.

GROSS: When you started off in movies during the war and lot of men...

Ms. ALLEN: Second World War.

GROSS: Yeah. And a lot of men...

Ms. ALLEN: We have to say that these days.

GROSS: Thatâs right. And a lot of men who had had jobs were off fighting the

war, so there were more openings. Do you think anything was more difficult for

you as a woman? Were there any obstacles put before you? Were people willing to

mentor you in spite of the fact that you were a woman?

Ms. ALLEN: Thatâs a word that wasnât used in those days. Nobody â I used it in

terms of â I think I used it earlier in the interview because I've heard it so

much lately.

GROSS: Right.

Ms. ALLEN: Obviously there are people who encourage you. I mean I never

would've been able to get ahead in anything because I was working mostly with

men, unless the men who helped me were encouraging. I mean thatâs, as far as

I'm concerned, it took in my generation, certainly, men to help women. You just

couldnât go blasting your way. After all, you had to â the hardest thing to do

is to be able to learn everything of what goes on in a laboratory and not be

considered a, you know, an overbearing ballbuster, is the word that they used

to use. I guess they still do. They use worse words now.

Anyway, itâs very hard to retain yourself as a woman and still be

knowledgeable. And the only way you can do that is to learn everything you have

to know about everything so that nobody can fool you, and laboratories were a

wonderful place because I ended up with great relationships with people in labs

because I had come from having cut commercials and industrials and laying out

my own opticals.

So I knew labs and I knew the people who did the opticals and I knew what you

could do. And when you know your stuff, they respect you. They donât think of

you as a man or a woman. But it took in every new relationship in the early

days. It took going through that period of learning that I really didn't know

what I was talking about. So you had to work harder.

DAVIES: Dede Allen speaking with Terry Gross in 2000. Allen died Saturday at

the age of 86.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

126189658

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20100423

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

In 'Handsome Harry,' Guilt Plays A Starring Role

(Soundbite of music)

DAVE DAVIES, host:

Bette Gordon is known to some moviegoers for her 1984 indie film âVariety,â

about a woman who takes tickets at a porn theater and becomes obsessed with

watching men watch women.

Her new film âHandsome Harryâ is about male sexuality. It stars Jamey Sheridan

as the title character and features Campbell Scott, Steve Buscemi, John Savage

and Aidan Quinn.

Film critic David Edelstein has this review.

DAVID EDELSTEIN: One way to think of Bette Gordon's âHandsome Harryâ is as a

revenge movie turned backwards and inside out. That is, the bad guys take

revenge on themselves. Thirty-three years after they did a very bad thing,

they're still eaten away by guilt, and one of them goes on a kind of pilgrimage

to ask forgiveness from the person who was violated.

The pilgrim is Harry, once dubbed "Handsome Harry," a divorced Albany, New York

contractor played by a brilliant actor named Jamey Sheridan. He has a long,

somewhat flat face that can seem a mask of blandness or take on, in the movie's

shadowy lighting, a faintly satanic cast. It's the face of a man with a secret,

and also, perhaps, of a man who keeps secrets from himself.

Shortly after his 52nd birthday, Harry receives a call from an old Navy buddy

on his deathbed - Kelley, played by Steve Buscemi. A long time ago, Harry,

Kelley and three others drunkenly brutalized a fellow sailor, Kagan, they

learned was gay. In his hospital bed, Kelley's memories flood back.

(Soundbite of movie, âHandsome Harryâ)

Mr. STEVE BUSCEMI (Actor): (as Tommy) You remember the night Kagan took us to

the Five Spot and you two busted my (bleep) because I never heard jazz before?

Mr. JAMEY SHERIDAN (Actor): (as Harry) Yeah.

Mr. BUSCEMI: (as Tommy) Tell you, that was the most beautiful (bleep) sound I

ever heard. In fact, that was one of the best nights I've ever had in my whole

entire miserable life. To tell you the truth, Harry, I'm not even that sorry

see it end. I just donât want to go to hell.

Mr. SHERIDAN: (as Harry) Youâre not going to hell.

Mr. BUSCEMI: (as Tommy) You donât know that. I'm pretty sure it was me who

(bleep) Kagan so bad.

Mr. SHERIDAN: (as Harry) All five of us did that.

Mr. BUSCEMI: (as Tommy) I think I was the one who dropped that generator on his

hand.

Mr. SHERIDAN: (as Harry) Are you sure?

Mr. BUSCEMI: (as Tommy) Harry, just tell him I'm sorry. Please?

Mr. SHERIDAN: (as Harry) I will.

Mr. BUSCEMI: (as Tommy) You promise?

Mr. SHERIDAN: (as Harry) I promise, Tommy.

EDELSTEIN: Prompted by Kelley's death, Harry visits one old Navy mate, and then

another and another, heading south toward Miami, where the victim, Kagan,

lives. The structure is a little plodding. There's a buried secret, but it's

broadly telegraphed. But the movie's flaws in the end recede. Each of Harry's

encounters is strange, gripping and revelatory. None of these men has put that

night behind him. Yet none has coped with the memory in anything like the same

way.

Nicholas T. Proferes' screenplay breaks each meeting into vivid dramatic beats,

starting with glimpses of each man's broken life or marriage, followed by

Harry's awkward, inevitable, urgent question: Do you remember what happened

that night?

The actors are beyond praise. Buscemi is more gaunt and hollow-eyed than ever,

which is saying something. As an affluent, alcoholic realtor, John Savage plays

a man deformed by a messy, uncontainable rage. Aidan Quinn is a professor whoâs

channeled his guilt into an anti-military, anti-macho philosophy; this is the

film's least credible idea, but Quinn gives it weight.

Finally and most frightening is Titus Welliver as a born-again whose wife is a

paraplegic and who thanks the Lord in almost every sentence. The sight of him

clutching a golf club and fighting to keep his true bile from rising is

indelible.

Bette Gordon has radar for the uneasy posturing of the archetypal American

male, especially when the subtext is homosexuality. But her vision isn't

reductive. Harry is damned, but we still have glimpses of a larger spirit, of

the passionate man he was.

The victim, once a concert pianist, finally makes an appearance, although not

in the way we expect. He's played by Campbell Scott, and his restraint is far

more haunting than rage and tears. Kagan is a passive revenger. He has waited.

And Harry's sin, we learn, came from a different place than his buddies' blind,

stupid prejudice.

Underneath the revenge story in âHandsome Harryâ is a kind of ghost story.

Those ghosts aren't just the victims of hate, disfigured by a violent,

senseless world. The ghosts are also the victimizers - men like Harry who are

pale shadows now, having murdered what was best in themselves.

DAVIES: David Edelstein is film critic for New York magazine.

And with apologies to the great Merle Haggard, we have a correction. In our

review yesterday of Haggardâs new CD, âI Am What I Am,â we added a few years,

10 actually, to his age. What he is is 73 years old, and still walking the

floor over you.

For Terry Gross, I'm Dave Davies.

(Soundbite of song, âWalking the Floor Over Youâ)

Mr. MERLE HAGGARD (Singer-songwriter, musician) (Singing) You left me and you

went away. You said that you you'd be back in just a day. That day has come and

gone but youâre still away from home. I'm walking the floor over you.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

126174228

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.