A 'Handbook' to Robert Crumb

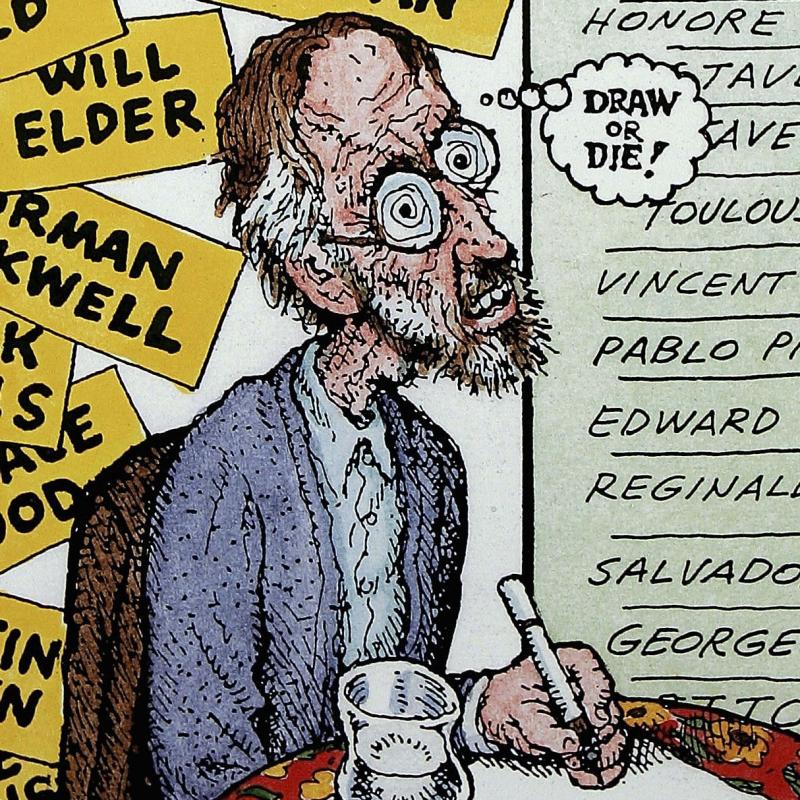

Underground comic book artist Robert Crumb has drawn comics for more than 40 years. Crumb, creator of Zap Comix, is the artist behind such 1960s and '70s icons as Fritz the Cat and Keep-on-Truckin. The new The R. Crumb Handbook is a visual biography of Crumb's life.

Transcript

DATE May 2, 2005 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: R. Crumb discusses his comic book art and new memoir

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest, R. Crumb, is the most renowned of the underground cartoonists who

emerged in the '60s. He created Zap Comix and such characters as Fritz the

Cat, Mr. Natural, the Snoid and Devil Girl. As Crumb once put it, quote, "If

you were a hip college student, you had to have a Zap Comic next to your dope

stash. I was America's best-loved underground cartoonist. I was cool. I was

ultra-hip. Yeah, sure," unquote. If Crumb wasn't exactly ultra-hip, he was

definitely extremely eccentric as a 1994 documentary made clear. Now he has a

new memoir called "The R. Crumb Handbook" that includes many of his comics, as

well as a CD featuring his music. Reviewing the book in Newsweek, Malcolm

Jones wrote, quote, "Crumb has made strange and hilarious art out of his own

neuroses. Insecure and paranoid, obsessed with sex in general and women with

big behinds, in particular, Crumb has never been afraid to draw and write

about his own foibles and fantasies. His work is like an id, unleashed with

no thought for propriety," unquote.

For the past few years, Crumb has been living in France. His recent work has

been published in the New Yorker. I spoke with him a couple of weeks ago when

he was visiting the US.

R. Crumb, welcome to FRESH AIR. Didn't your early comics, some of the ones...

Mr. ROBERT CRUMB (Underground Comic Book Artist): Yes.

GROSS: ...anthologized in your new book, do you think they look different out

of the time period than they did to you in their time?

Mr. CRUMB: Different from this perspective of nowadays?

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. CRUMB: Well, they're kind of timeless, you know, because they looked out

of time then, when I did them. In the beginning, in '66, '67, '68, people

looked at them and said, `Hey, these look like old comics from the '30s, you

know it?' And some people, when they met me, were surprised that I was a

young man at the time. They thought I'd be some old guy, because it--so they

already looked out of time then, and so I--they just kind of still look like

their own thing. They don't--and I think a lot of young people that pick them

up, they don't--when they first see them, don't realize how old they are.

GROSS: Huh!

Mr. CRUMB: They just don't seem to be part of the '60s as it's known,

stylistically, for such stuff as Peter Max or the psychedelic posters and all

that stuff. It doesn't fit in with that. It's kind of its own thing.

GROSS: In your new book, "The R. Crumb Handbook," you described how you

started some aspects of your style after a bad LSD trip. What were the...

Mr. CRUMB: Right.

GROSS: ...images that you saw when you were tripping that made their way into

your cartoons?

Mr. CRUMB: Whoa! That's a tough question. What were the images on LSD?

What did they look like? Ooh. Well, I don't know, for some reason, I don't

know why or how it happened, I just--on this one really strange LSD trip that

I took, that there was something wrong with the drug, I got trapped in some

level of the mental collective consciousness that was very tawdry and

carnival-like in a kind of a cheap, gaudy way. It's really hard to describe.

And that involved that kind of gaudy, low-grade cartooning styles of the '30s

and '40s and all that, as well as other kind of gaudy imagery and it just

stuck there. I was stuck there for months until I--actually, what cleared it

up was--taking another dose of LSD made it go away. But in that...

GROSS: How did it chase it away?

Mr. CRUMB: I don't know. It just evaporated with this--another strong drug.

Because, you know, LSD imprints very deeply in your subconscious. That's the

scary thing about it. It takes you to a deep, deep level of your mind and

then whatever you experience on that--in that time is imprinted deeply.

That's the thing about LSD that's serious to deal with, you know?

GROSS: Well, how do you think your drawing style was actually changed by this

hallucinogenic imagery?

Mr. CRUMB: Well, it changed vastly. Well, before that, I was trying to

be--you know, in order to get work as an artist and a cartoonist, I was trying

to be contemporary and with it. And I looked at the work of people like Jules

Feiffer and these English cartoonists like Gerald Scarfe. And I was trying to

be more modern. I was, you know, attempting to fit in with what was trendy at

the time. And the LSD just blew all that away completely, and I was--because

of that, being caught in that--for that two months in that period where--I was

always drawing in my sketchbooks all the time, and I was drawing these images

that were coming from my brain all the time in that two months,

uncontrollably, just floating up in my mind, and I just started drawing them.

And that completely changed my whole approach to what I was doing, to the

cartooning and took on this older '30s, '40s, kind of--and I starting looking

more closely at these kind of brand X third-rate comics from the '40s that

had--that were drawn in that style by these artists that never achieved, you

know, renown among--even among comics people. They were a third-rate artist,

but they had this working-class proletarian, funky, crude, vulgar--these

comics were very vulgar, violent, you know, real cheap, violent comics. I

don't know. It's interesting.

GROSS: So what are some of the characters that you started drawing in this

period after taking LSD?

Mr. CRUMB: That was my first--you know, that two-month period when my ego was

completely, like, fragmented by that bad LSD, I drew Mr. Natural, Flakey

Foont, Angelfood McSpade, the Snoids, the Vulture Goddesses, the Vulture

Demonesses, whatever you want to call them. I know lots of characters--The

Old Pooperoo.

GROSS: OK, Mr. Natural's this kind of, like, guru kind of figure with the

long...

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah.

GROSS: ...really long beard. Was he based on anybody who you knew or a type

that you knew?

Mr. CRUMB: It was actually, more or less, a combination of the mysticism of

LSD experiences, combined with this old cartoon stereotype of the little old

man with the long beard.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. CRUMB: There was several of these, kind of like, standard, you know,

cartoon figure in old comic strips going back to the '20s, even earlier,

probably, that little old--funny little old man with the long beard.

(Unintelligible) invent anything out of whole cloth. It's--all has

antecedence in the popular culture, all of it.

GROSS: And Angelfood McSpade--I mean, this is an African-American woman who

is drawn like--some of the black people in your early comics look like the

African cannibals in the Betty Boop cartoon where they...

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah.

GROSS: ...have her in a big pot and...

Mr. CRUMB: Mm-hmm. That's right, exactly.

GROSS: Yeah. Why...

Mr. CRUMB: Precisely.

GROSS: Why did you draw them that way?

Mr. CRUMB: Because they were there and they were part of the whole experience

of all that tawdry, low-class imagery that was boiling in my brain. That was

part of it is that jigaboo jungle bunny image, that was there. It was part of

it. It wasn't there before, but it boiled up, and so it's obviously in the

collective subconscious and I just didn't have any control. I just had to

draw what was there. And I don't think Angelfood McSpade can really

legitimately be called an African-American woman. That's a car--it's a

cartoon stereotype crazy...

GROSS: OK.

Mr. CRUMB: ...image of something that's like in the imaginations of people.

It's not, you know, actually a representation of an African-American woman.

GROSS: Did you worry that people would misconstrue it? Because certainly a

lot of people didn't see it that way. They just saw it as a crude stereotype.

Mr. CRUMB: Yes, they do. A lot of people just took it at face value. And,

you know, I can't let that stop me. Like, it has to come out. What's been in

there had to come out. Had--you know, I really couldn't stop it. And I--if I

worried about how it was going to be construed too much--I mean, I had--well,

obviously, I had some concern of that, but, I--you know, I didn't want to be

too hurtful, but at the same time, I had to put on the paper--I had this

direct line from, you know, the brain stem to the paper. There was

no--I--things in between I just--were brushed aside, everything in between,

the super ego, you know, the socialized self, you know, all that was just

swept away.

GROSS: And it was swept away in your sexual imagery, too.

Mr. CRUMB: You betcha, yeah. So, you know, I--yeah, I have no secrets. I'm

probably one of the few human beings on the planet--I have no secrets.

Everybody who looks at my comics knows exactly what I'm about. It's all

there.

GROSS: Everybody knows what your sexual fetishes are and everything.

Mr. CRUMB: The darkest side of me, it's all on paper. I--you know, so that

makes--allows me to be a pretty nice guy in real life, you know? So it's all

out there on paper. It's foisted on the public.

GROSS: But was there ever a part of you that wanted to censor that part of

your mind or at least...

Mr. CRUMB: Of course.

GROSS: ...kind of keep it private and hidden, which is what most people do

with those?

Mr. CRUMB: Of course.

GROSS: Uh-huh.

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah, sure. I'm a normal person in that way. You know, before

those LSD experiences and I just decided to let that all out, I used to make

those drawings and tear them up and flush them down the toilet. `Oh, this is

terrible. What's wrong with you? Where is his wife?' You know? But--and

also as I started doing it for publication, then it all--then the floodgates

opened. You know, once you just let a crack in the dam and let a little bit

trickle out, then it all starts to--the crack just got wider and wider until I

just let it all out. Let it all out there. Oh, look, the dark side of

myself, it's all out there. I had a lesson at impulse. Now I think I got it

out of my system, a lot of it.

GROSS: Huh!

Mr. CRUMB: I'm old now.

GROSS: My guest is comic book artist R. Crumb. His new memoir, "The R. Crumb

Handbook," includes many of his comics, as well as a CD of his music. We'll

talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is R. Crumb, and he has a new autobiography in words and

cartoons. It's part anthology...

Mr. CRUMB: Right.

GROSS: ...part extended essay. It's called "The R. Crumb Handbook."

OK, so once you started doing these like real personal--like, the dark side of

R. Crumb cartoons...

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah.

GROSS: ...that was in this hallucinogenic 1930s kind of imagery...

Mr. CRUMB: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...it really caught on. I mean, you really struck a nerve. You were

like one of the originators and kings of underground comics and all the...

Mr. CRUMB: That surprised the hell out of me at the time.

GROSS: Uh-huh.

Mr. CRUMB: I was completely surprised by how--the appeal that it had. It

surprised me.

GROSS: What was it like for you to go from, like, loner, eccentric weirdo...

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah.

GROSS: ...to, like, in-demand...

Mr. CRUMB: Right.

GROSS: ...popular person...

Mr. CRUMB: Right. Cool Mister...

GROSS: ...who everybody wants to publish and buy, and know.

Mr. CRUMB: Right. Mr. Cool Guy. It was very disorienting because I was

quite young. I was only, like, 25, 26 when all that happened, originally.

And it was both, you know, thrilling to my ego--I had a big ego--but also

very confusing and scary, even, because, suddenly, this whole element of

people that I'd never, ever had any dealings with before were suddenly there,

interested in me, wanting to hustle me, wanting this and that and everything,

you know, get--sign me to a five-year exclusive contract, da, da, da. You

know, these people are trying to cash in on the hippy culture and the youth

movement, and make money off it, you know, and they saw me as, you know,

somebody--a part of that that they could exploit, like the people that made

the Fritz the Cat movie--they were, you know, textbook case of these

media hustlers, you know. And I was so young, I didn't know how to deal with

all that.

But at the same time, it made me more attractive to women. So that part of

it was nice.

GROSS: (Laughing) So...

Mr. CRUMB: It was. Before that I was, like, this, you know, nerd that at a

party no woman even noticed. I was just part of the shrubbery or something.

But after that, `Oh, there's R. Crumb. Oh.' You know? Suddenly, they were

interested, and that was nice.

GROSS: Well, you were also, like, suddenly, you were an important part of,

like, the hippy counterculture. Did you identify with that culture? Did you

feel like a part of it?

Mr. CRUMB: Well, I guess, you know, the elements of that culture, like, the

music and the stylistic stuff--no, I didn't identify with that at all. I

identified with some of the values, like the political values, some of, like,

the Eastern religious stuff that people were into--I like--I was attracted to

that; and, you know, the drug thing, the psychedelic drugs--I was into that

part of it. And I also got caught up in the general optimism and hopefulness

and idealism of that time, the late '60s, you know? But stylistically, I was

always alienated from it. I hated the music.

GROSS: And I want to get back to some of the early imagery in your mind. In

your new book, in "The R. Crumb Handbook," you write a little bit about

the pop culture that you were surrounded with as a kid.

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah.

GROSS: And you write that puppet and marionette kid shows made a deep

impression on you.

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah.

GROSS: You say the adult assumption...

Mr. CRUMB: Oh, yeah.

GROSS: ...was that these puppets were cute and lovable, but they were

actually...

Mr. CRUMB: Right.

GROSS: ...grotesque. And the shows tried to tell kids that life could be fun

and exciting, but the unconscious message was that the adult world is strange,

twisted, perverse, threatening, sinister. What was it about...

Mr. CRUMB: That's right.

GROSS: ...like "Howdy Doody" or the other--"Kukla, Fran and Ollie"--that you

found, like, grotesque and sinister?

Mr. CRUMB: Oh--well, especially "Howdy Doody." I think that it was really

grotesque. `Hi, kids!' And Clarabell the Clown and all the--oh! It was

all very, very sinister and scary. And Buffalo Bob Smith--did you ever see

that stuff when you were a kid?

GROSS: You bet. I sure did.

Mr. CRUMB: Jeez. My wife, Aline, actually--she grew up in New York. She

actually got to be in the Peanut Gallery when she was a kid on the Buffalo Bob

show and the "Howdy Doody Show." And she said it was a defining moment in her

life. She was, like, eight years old or something--seven years old. And she

saw the adult world behind the scenes of the "Howdy Doody" show and how these

people are all kind of cranky and stressed. And she said the seat of the

pants of Bob Smith's outfit was kind of frayed, and, you know. (Laughing) And

he was, like, real mean to the kids when it was off camera.

GROSS: So...

Mr. CRUMB: "Kukla, Fran and Ollie" was cuter, though. "Kukla, Fran and

Ollie"--that was better than "Howdy Doody," that way, it was more lovable.

You know, Kukla was kind of a cute little lovable guy, a little hand puppet.

And Fran, the woman, she's, like, talking to the puppets. So it was a little

more reassuring; you know, it was cuter. But...

GROSS: Did the frozen smile on Howdy Doody's face strike you as deranged?

Mr. CRUMB: It was just creepy and weird. What the heck, you know? What

does that have to do with anything? He didn't look like a kid--he was

supposed to be, like, a kid in a cowboy suit, but he didn't come off like--he

just came off as a creature, like, from Mars, you know? He wasn't--there's

some underlying thing you can't quite define that was just disturbing and

sinister and scary about it all, all that stuff.

GROSS: OK, the things that you say about these puppet shows, that they show

that the adult world is strange, twisted, perverse, threatening,

sinister--that's...

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah.

GROSS: ...a kind of description of what your cartoons became like--strange,

twisted, perverse, threatening, sinister. It's like, that's what you set out

to do.

Mr. CRUMB: Well, yeah, but I guess...

GROSS: Not for children, of course. I mean, it wasn't for children.

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah. What I was trying to do was to uncover that sinister

quality, the dark, sinister, strange, disturbing part of things and not hide

it, not keep it hidden. You know, I started doing that in '68, '69, putting

it out there, the Snoids. You know, they were these little, creepy gnome

creatures that I, you know, on LSD, I would catch out of the corner of my eye

sneaking around and giggling in the background of my life, you know?

GROSS: (Laughs)

Mr. CRUMB: I just had to show that, I wanted to show that, that sinister

aspect, that noire, dark side of things, and how it's--I guess it's almost

like making fun of the veneer of cuteness or whatever it is that they think

covers that. You know, it's just all veneer. It's not real cuteness, it's a

completely fake attempt to cover up what life is really about, and, you know,

the whole mass media thing. And we're all--grow up in America, you're a

child of the mass-media pop culture unless your parents, like, guard you and

protect you from that very conscientiously. My parents didn't--they shoved

us in front of the TV and, you know, bought us all the comic books and

everything. So when I was a little kid, they didn't--you know, some people I

know, their parents frowned on comics, but my mother bought us comic books

when we were little. So we're just products of pop culture. So, you know,

that's what you have to work with.

GROSS: You know, we've talked a little bit about how your visual imagery was

changed by LSD. What about your sexual fantasies? I mean, so much of the

comics that you've done...

(Soundbite of goofy laughter)

GROSS: ...have had to do with...

(Soundbite of goofy laughter)

GROSS: ...sexual fantasy. You know, what...

Mr. CRUMB: Hi, girls.

GROSS: Were those fantasies as dark before LSD as they were after?

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah. Unfortunately, the LSD didn't really change much of my

sexual fantasies, but I found a way to express them that made them

metaphorical to me. I could solve them more metaphorically, you know. On

LSD, everything in our world is a metaphor. Or, as Allen Ginsberg said,

things are symbols of themselves. And so I saw my own sexual fantasies that

way, and tried to understand what they meant metaphorically. You know,

otherwise, we just feel helpless in the face--if things don't mean anything,

we feel helpless. What does it mean? What do these fantasies mean? Where do

they come from? Why do I have them, you know?

GROSS: So...

Mr. CRUMB: Try to understand or express that somehow, in some way. But of

course it's all masturbatory on top of that, you know.

GROSS: Well...

Mr. CRUMB: I got off drawing those things. I got off drawing them. I admit

it, I confess.

GROSS: But that's--I wanted to ask you about that. Did you want your more

sexually oriented comics to function as turn-ons, to be like pornography...

Mr. CRUMB: No. No.

GROSS: ...in the lives of its readers, or did you want...

Mr. CRUMB: No, I didn't. No. It was only for myself. I had no motive to

turn other people on to my sexual fantasies or my sexual preferences at all.

It was just expressing what was inside myself in some way that revealed,

hopefully, the metaphor that it was, you know, in the many variations of

that; you know, the Angelfood McSpade, the Vulture Demonesses or the

Bigfoot-Sasquatch character that I did, the big, hairy female, or the

Devil Girl character; these are all--and when feminists complain, say, `These

aren't real women, these are Crumb's fantasies,' they're absolutely right. I

can't--you know, I got no argument with that. Yeah, that's what it is. Yeah.

It just all comes out of my mind.

GROSS: Well, in your new book, you describe yourself as sexually in a state

of arrested development. You say...

Mr. CRUMB: Right.

GROSS: ...`All my natural compulsions are perverted and twisted.'

Mr. CRUMB: Right. Right.

GROSS: So...

Mr. CRUMB: I see myself as a very negative person, actually. I'm almost

like a negative of the normal, well-adjusted guy, you know. Everything that

he is, I'm not, and everything I am, he's not, you know. It's almost how I

see myself. Maybe not 100 percent, but, you know? I'm like the person of

the night, he's a guy of the day, you know, etc., etc., you know.

GROSS: Now, when you were young, you went for a while to Catholic school,

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah.

GROSS: For a while, you went regularly to church. You say you went

through...

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah. Oh, yeah.

GROSS: ...a period of being fervent and devout.

Mr. CRUMB: Religious, yeah.

GROSS: What happened to all those fantasies that you had during this period

when these fantasies would've just been horrifying to you?

Mr. CRUMB: Oh--horribly. Horrible guilt. Horrible guilt, of course.

Praying desperately. Please, God, what is this about?

GROSS: Did you pray to get rid of these thoughts?

Mr. CRUMB: You know, it's a funny thing. The same time the thoughts

were--those fantasies were attractive and gave me pleasure, and at the same

time I was deeply disturbed by their sinfulness. So something had to go, and

what went was the church and the whole sin thing. That had to go.

GROSS: R. Crumb will be back in the second half of the show. His new

memoir, "The R. Crumb Handbook," includes many of his comics as well as a CD

of his music.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

(Announcements)

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Coming up, comics based on sexual fantasies and acid trips. We

continue our conversation with cartoonist R. Crumb. We'll also talk about

his collaboration with Harvey Pekar on the series "American Splendor."

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross, back with R. Crumb, the king of

the '60 underground cartoonists. He created Zap Comix and such characters as

Mr. Natural and Fritz the Cat. His came out of his dreams, nightmares,

fantasies, LSD trips and sexual obsession. He has a new memoir that includes

many of his comics. It's called "The R. Crumb Handbook." When we left off,

we were talking about how his sexual fantasies influenced his comics and how

politically incorrect those fantasies were.

So you quote one woman in your book as accusing you of ruining underground

comics by encouraging all the younger boy artists to be bad and do comics...

Mr. CRUMB: Mm-hmm. Right.

GROSS: ...about their own horrible sex fantasies.

Mr. CRUMB: Right.

GROSS: Do you feel like your comics inspired a lot of...

Mr. CRUMB: Other artists?

GROSS: ...other comics of--yeah, of kind of, you know, bad sexual...

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah, I did.

GROSS: ...misogynists? Yeah. Uh-huh.

Mr. CRUMB: Well, you know, it opened the gates for other young boys who had

these--who probably were also comic nerds when they grew up, and that's why

they're drawing comics, and so they also had the same kind of frustrations and

resentment towards women, who were the same kind of--not precisely--I never

saw anybody else draw precisely the same kind of stuff that I drew about sex,

but, you know, similar things or just--it allowed them--it permitted them,

when they saw my work, `Crumb, he's cool and he's doing it so, you know, I

guess I can draw stuff that puts women in this position, too, but--you know,

of having violent acts committed against them.' But I don't think--I can't

think of any artist off hand who was like totally obsessed with just drawing

brutal violence against women. I think that's just--but, you know, feminists

and other people that are involved in any kind of, you know, political

obsession like that, and you can't blame them for it. There's no--they're

looking for that, so they're looking, `Oh, here's one right here. Look,

here's an example of, you know, somebody being violent to women or here's

somebody abusing a woman.' You know, they're looking for that and, yeah,

sure, you can find it. It's there. Yeah.

GROSS: Do you...

Mr. CRUMB: But I--point in my defense is I don't think I ever drew it in such

a way it could be taken as propaganda for behavior like that. I don't make

that sort of behavior towards women look heroic or commendable. I mean, the

characters that are doing those things are always, you know, creepy little

twisted guys. They're not, you know, heroic, virtuous images of--that someone

would want to emulate.

GROSS: So do you see this part of your work as almost like a grotesque satire

of your sexual fantasies?

Mr. CRUMB: Well, satire?

GROSS: No, not quite, huh?

Mr. CRUMB: Not quite satire, no. It's more...

GROSS: Wishful thinking on my part.

Mr. CRUMB: Much more--it's much more personal than that. It's more personal

than that, you know. It's a personal revolution, you know. And for what it's

worth then, you know, if it's painful for you, if you can't look at it, then

just don't look at it.

GROSS: Now we talked a little bit about how influenced you feel you were by

early comics and, you know, musically so much of the music you love is from

the '20s and '30s.

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah.

GROSS: How were you first exposed to, like, graphics of that period and music

of that period?

Mr. CRUMB: Right, right. Well, as a kid in the '50s, you didn't watch a lot

of television, and at the same time you saw the culture around you. I saw,

when I was nine, 10, 11 years old, you could see the popular culture was in

decline. It was--comics were in decline, the TV wasn't that great, you know,

and so I start looking for older stuff, and the first older stuff that I--you

know, that piqued my interest was older comic books that you could find in

Salvation Army stores, and also old stuff on the kiddie shows on television.

Again, you have to keep in mind we're just children of the popular culture.

There was no channel to higher forms of literature or art or anything. It was

all pop culture. So on TV on these kiddie shows they showed old cartoons from

the '30s, you know, old Betty Boop and Popeye and all that stuff, and the

music was great, the drawing style was great, they were very, very appealing

to me as a kid. This was '53, '54, '55, in there. And the music was--I don't

know, just grabbed me somehow and then also you could see these really old Hal

Roach comedies, "Laurel and Hardy," "Our Gang," "Little Rascals," stuff--I

loved that stuff when I was a kid.

And as I got into my later teens, I always looked for really early movies that

were on TV on the late show, movies from 1930, '31, '32. I just loved the

whole style of the period. Somehow it just attracted me deeply, the music and

everything. And then I started looking for some other way to find the music

of that period, 'cause I loved hearing it in the TV, reruns of those old

films, and I discovered on 78 records. I discovered that this old music was

actually on these records that were sitting around these same places that the

old comic books were and other old stuff, and so I started buying old 78s and

still collecting them today.

GROSS: And how did you start playing banjo?

Mr. CRUMB: I had musical inclinations from childhood and I--first I tried to

make myself a cigar box ukulele, but that didn't play so well and I couldn't

really make it play efficiently and effectively, so then my mother, for

Christmas when I was 12 years old, gave me a plastic ukulele, which was

playable and could actually tune it and play it, so I learned to play that.

And then I graduated to this banjo later. I was, like, attracted to old music

and--you know, kind of out-of-it nerd. I, you know, wasn't really much into

rock 'n' roll, things of my contemporaries. I don't know. I just--like I

said. I'm not gonna go negative. I'm kind of an oddball character.

GROSS: Well, speaking of your music, the autobiography comes with an R. Crumb

music sampler that...

Mr. CRUMB: Right.

GROSS: ...includes records from the '70s that you made with The Cheap Suit

Serenaders...

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah.

GROSS: ...and stuff that you've recorded since moving to France...

Mr. CRUMB: Right.

GROSS: ...as well as some tracks that you recorded with your family. And I

thought maybe we'd play one of the recent ones that you've made with your

family.

Mr. CRUMB: Huh. Oh.

GROSS: With your wife and daughter playing with you, and you're singing.

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah, yeah. Sophie is...

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. CRUMB: Sophie's really a good musician, really good musician. Much

better than me.

GROSS: So what do you think? Would you rather play something earlier? I

mean, 'cause I love all the stuff, so I'm amenable to any of this.

Mr. CRUMB: Play "Baby Face."

GROSS: Sure. OK. So why don't we hear "Baby Face," and tell us who's

playing what on this.

Mr. CRUMB: Sophie plays piano on it and I play guitar, and I sing on it, I

guess, yeah.

GROSS: OK, and this was recorded in 2003, the Crumb family.

(Soundbite of "Baby Face")

Mr. CRUMB: (Singing) Baby face, you've got the cutest little baby face.

There's not another one can take your place, baby face. My poor heart is

jumping. You sure have started something. Baby face, I'm up in heaven when

I'm in your fond embrace. I didn't need a shove 'cause just fell in love with

that pretty baby face.

GROSS: That's the Crumb family. That's R. Crumb, his wife Aline and his

daughter, Sophie, recorded in 2003, and it's on a CD that comes with the new

R. Crumb autobiography in words and comics which is called "The R. Crumb

Handbook."

Mr. CRUMB: Right.

GROSS: Before you started doing underground comics...

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah.

GROSS: ...you worked for American Greetings.

Mr. CRUMB: Right.

GROSS: Now were you doing greeting cards or...

Mr. CRUMB: Yes. Yes. I drew hundreds and hundreds of greeting cards.

GROSS: Gosh, I'd like to see those. Have they been exhibited?

Mr. CRUMB: No.

GROSS: What were they like?

Mr. CRUMB: They're pretty bland. They're bland. I didn't write them, I just

did the drawings. They had a staff of writers, and you went to work--it was a

9 to 5 job. You punched a time clock. It was in Cleveland. And I got up at

6:00 in the morning and took the rapid transit to work every day and, you

know, went to the bar after work and drank with the guys and then went home

and asked myself, `Is this my life? Is this what my life is gonna be from now

on?'

GROSS: So what are some of the things that you drew for the greeting cards?

This was--What?--birthday cards, get well soon cards, stuff like that?

Mr. CRUMB: No, I had this department that--at that--in the late '50s they

started making these kind of more hip-looking greeting cards. They were tall

and thin, you know. Remember those?

GROSS: Yes, I sure do.

Mr. CRUMB: That was--I was in that department.

GROSS: And they were funny or funny in quotes.

Mr. CRUMB: Funny. Yeah, they were funny.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. CRUMB: And some of them actually were funny. They had a couple of

writers that actually were gifted comedy writers who just got stuck in

Cleveland 'cause they were alcoholics or whatever. But they wrote very funny

cards. Often their best cards were censored and never used because everything

had to pass by the approval of the wife of the guy who owns the Walgreen drug

chain, and if she didn't like the cards, then they couldn't be distributed.

So some of the best stuff never actually got distributed.

GROSS: My guest is comic book artist R. Crumb. His new memoir, "The R. Crumb

Handbook," includes many of his comics as well as a CD of his music. We'll

talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is R. Crumb. His new memoir, which includes many of his

comics, is called "The R. Crumb Handbook."

We've talked about how you love old things from the 1920s and '30s. You

collect a lot of old things.

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah. I'm just an old moldy ...(unintelligible) love old stuff.

GROSS: Yeah, now how--you've also said you're repulsed by the body. You say,

`I hate my body.'

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah.

GROSS: `The thought of my internal functions, the organs, digestion'...

Mr. CRUMB: Oh.

GROSS: ...`the brain, the nervous system horrify me.'

Mr. CRUMB: Oh. It is horrifying. Yeah.

GROSS: What's it like for you to be getting older now when, you

know--you're--like your body just becomes a little less functional as you get

older, and all of those...

Mr. CRUMB: I know.

GROSS: ...freaky things about your digestive system or whatever become more

evident?

Mr. CRUMB: Well, you know, you're forced to pay more attention to the body as

you get older. You're forced to. And that has helped me in a way to be less

repelled in a certain way 'cause, you know, before I was just ignoring it as

much as possible, you know, so that kind of helped to keep that or nurture

that kind of horror of the body. Actually being forced to deal with it, you

know, actually even forced to have a certain affection for the body, otherwise

if you don't, you're in big trouble, you know. You don't develop some sort of

respect and even a kind of almost a sympathetic fondness for your body and--or

at least, you know, a mercy for the body, a sense of mercy, you know, lighten

up on the body, ease up on it, do give it a chance, you know, acknowledge that

it needs, you know, some care and feeding and, you know. And so now I have to

pay more attention.

GROSS: Do you draw--do you think of yourself as drawing yourself very

differently now than you did in the '60s or '70s?

Mr. CRUMB: Not too differently. Maybe a little academically more correct. I

look at my drawings that I did back then and I can see a lot of things that

are real crude about them and not--I would change a lot of things if I

actually could--was Superman, could go back and alter everything I ever drew.

I would change a lot of it, improve it. So I think I--my drawing's actually

improved technically in a way, although maybe the content's not quite as wacky

and wild as it used to be. I don't know, but I draw myself looking older now.

I always drew myself looking old anyway. I always felt old.

GROSS: Why? Why do you think you always felt old?

Mr. CRUMB: I don't know. My mother used to say, `Robert, you're just like a

little old man.' She used to tell me that when I was a kid. I don't know. I

always did. Actually part of my opposition to normal people is that I feel

like I was born old, in a certain way I've actually gotten younger as I've

gotten old--as life's gone on. Or most people it's the opposite. They come

out like children and then they get old. I think I came out old and I'm

becoming a child as I get--as the years progress.

GROSS: Let me quote something else you write in your book. You say that in

your youth your sex drive never left you alone. You say, `I was constantly

driven by frustrated desires to do bizarre and unacceptable things with and to

women.'

Mr. CRUMB: Oh, yeah.

GROSS: `My soul was in constant conflict. Old age is the only relief.'

Mr. CRUMB: Right. Yeah.

GROSS: Well, you're not exactly in old age, but you are older.

Mr. CRUMB: I'm 61. That's old age. It's old. I think once you pass 60 you

can't call yourself middle aged anymore.

GROSS: So is that--do you feel like that's had an impact on what you want to

draw?

Mr. CRUMB: It had an impact even on the motivation to draw at all actually.

GROSS: How?

Mr. CRUMB: I just don't have--I was so driven when I was young, I used

to--when I was young, I lived on paper basically. I lived my youth on paper

'cause I couldn't live in the real world. I guess part of that thing you just

asked me before of how do I feel like I'm younger now is that I actually

can--am more relaxed in the real world than I used to be, so I'm much less

motivated to hide behind the drawing in a certain way.

GROSS: Oh, this is really funny. The--you write in the book, `Sartre said

hell is other people.' You say, `Hell is also yourself.'

Mr. CRUMB: Right, right.

GROSS: I really like that.

Mr. CRUMB: Right.

GROSS: Now you moved to Paris decades ago. When was that?

Mr. CRUMB: Well...

GROSS: I don't mean Paris. I mean France.

Mr. CRUMB: We moved to France in '91.

GROSS: Oh, I thought it was longer ago than that.

Mr. CRUMB: Fourteen years ago.

GROSS: All right. OK.

Mr. CRUMB: Fourteen years ago this month. It was mostly--that was my wife's

motivation, moving to France. I would never have taken on something that

drastic in my own volition.

GROSS: Oh, I thought you were trying to, like, get away from your own fame or

something.

Mr. CRUMB: That's--no escape. But, Aline, she really wanted to move to

France. She--we'd been going to France frequently and she just fell in love

with the place and wanted to move there and get out of California, so--and she

took care of everything. She took care of the whole moving and all the

bureaucratic stuff and the documents and getting the mover and all. She did

everything, so I just went along with it. I'm kind of a passive guy that way

in the real world. I'm very passive. I'm only really active and aggressive

or assertive in my work.

GROSS: Do you like living in France?

Mr. CRUMB: The real world I'm a--in the real world I'm a very timid person

actually. Do I like--yeah. Oh, yeah. It's a really nice place to live,

France.

GROSS: You've described your mind as a garbage trail of mass media images.

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah, sure.

GROSS: So you...

Mr. CRUMB: Grow up in America, you can't help it. Grow up in America,

everybody's mind in America is a garbage pail of mass media input. Just can't

help it.

GROSS: When your daughter was growing up, did you want to, like, regulate

what was input into her brain, or did you want her...

Mr. CRUMB: Yes.

GROSS: You did. Why?

Mr. CRUMB: Yes, we did. Because there's so much garbage made to appeal to

kids, you know. It's a horrible, cynical, hideous thing the way they try to

reach kids, you know. It's bad. It's awful. And it's--they're so good at it

now, it's scary. So we try to control what--you know, to some degree.

Not--now you can't shield them too much 'cause then they'll see it at other

kids' houses and they'll rebel against you and all that stuff, you know. So

we didn't want to be too fanatic but we--you know, what I really wanted to do

with Sophie was give her a classical education in, you know, The Three

Stooges, Laurel and Hardy, the Marx Brothers, Betty Boop, Popeye, Little Lulu.

I used to read her Little Lulu comics, old ones from the '40s and '50s, and

she got to love those Little Lulu, you know. And Walt Disney, Donald Duck,

the old ones from the '50s which were great. They were--you know, I had

already sifted that stuff out for myself, and now she's kind of--she's got

that foundation that's really been--I can see that--I'm really glad I did it.

I'm really glad I did it. Other kids her age don't know anything about that

stuff, and all they know is the crap they grew up with in the '80s and '90s,

kids her age, you know.

GROSS: What did you most want to protect her from? What kind of pop culture?

Mr. CRUMB: You know the stuff on TV, stuff for kids on TV. She watched

"Sesame Street," that was OK, and, you know, a couple other things, but there

was so much bad crap, so we just substituted stuff that was better, the older

stuff that we had selected out--I had selected out and, you know, she

got--Sophie loves "The Three Stooges." She can--you know.

GROSS: R. Crumb is my guest and he has a new book that's an autobiography in

words and comics and it's called "The R. Crumb Handbook."

Are your dreams a lot like your comics?

Mr. CRUMB: My dreams?

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. CRUMB: Well, be--no, I guess--sometimes I have sexual dreams that are a

lot--you know, they're just right in line with my fantasies. I read this

thing recently written by some weird mystic writer that when you have

fantasies like that, sexual fantasies and you--they excite you, that you build

a thought form--he called it a schema or a schemata in your mind. That

thought form takes on a life of its own that once it's there, it's like

implanted in your mind, this thought form is like an entity that then

has--control you. Has a huge amount of control over you and keeps you in a

weak state, so that you're always, like, struggling with this thing to not let

it totally dominate you, 'cause as he points out, this mystic writer, that

this thing can dominate you so much that it'll--and you'll end up committing

suicide because it never actually fulfills you and leaves you--like taking

heroin or something, it leaves you bereft and feeling depressed and empty

because it doesn't re--it just takes your energy and doesn't--it can't give

back. It's just a mental thought form.

GROSS: Yikes.

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah. So that's kind of went this fantasy thing that I've dealt

all my life is--and it comes in my dreams a lot. It appears in my dreams and

it's very powerful. It's a very powerful female thing. It's a female entity.

GROSS: My guest is comic book artist R. Crumb. His new memoir, "The R. Crumb

Handbook," includes many of his comics as well as a CD of his music. We'll

talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is R. Crumb. His new memoir, which includes many of his

comics, is called "The R. Crumb Handbook."

There's one more image I want to ask you about from your work, and that's the

truckin' image where...

Mr. CRUMB: Oh. Oh.

GROSS: Right. OK, so we've got, like...

Mr. CRUMB: Oh.

GROSS: ...the big foot and everything, but there's always the--one hand has

like a forefinger in the air kind of shaking it. Does that...

Mr. CRUMB: That's gonna...

GROSS: That's gonna...

Mr. CRUMB: Keep on truckin' is gonna be written on my gravestone.

GROSS: Yeah. Did that come from, like, your interest in early jazz

recordings or something?

Mr. CRUMB: That all came out of that period--that two-month period when I was

in that fuzzy state from that bad LSD...

GROSS: Oh.

Mr. CRUMB: ...and it was all part of that imagery that was bubbling up in my

brain was these stupid-looking cartoon characters doing those kind of

'30s--1930s dance steps, you know, in unison, and this really stupid, you

know, stiff, animated, electrical--it's really hard to describe. It was all

part of that, all floating around in the collective consciousness, you know,

that nonsense, and I was drawing, and I didn't draw it with the intention of

it being something like cute and positive. Do me it was like a dance of

death. But the people interpreted it as--when they saw it--as something like

a part of the positive up-thrust in the late '60s and then it was picked up

by, like, merchandisers and it was on patches and lunch boxes and mud flaps

and every damn thing, and radio deejays were saying every 10 minutes, `And

don't forget to keep on truckin'.' And it became...

GROSS: What about the Grateful Dead song "Keep On Truckin'?"

Mr. CRUMB: Well, that came out before I did it actually.

GROSS: Did it? Oh, OK.

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah. It was--and Donovan and Grateful Dead did "Keep On

Truckin'" song before I ever drew that thing. It was, you know, an old

popular song from the '30s, "Keep On Truckin'." And it became--for me it

became a big legal nightmare and this lawyer and--oh, it was awful.

Everybody--anybody says `keep on truckin',' just goes through my nervous

system like a jolt or `slowly I turn, step by step, inch by inch.'

GROSS: So one more question: How much time do you actually spend drawing

comics now?

Mr. CRUMB: How much time do I spend drawing comics now?

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. CRUMB: I don't draw--I rarely ever draw comics anymore. Mostly I just do

business or things like this, you know. The media, they really want me, and

I'm too timid and insecure, so I say yes, and I end up doing this kind of

stuff.

GROSS: So this interview is a sign of insecurity?

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah, yeah.

GROSS: If you were more secure you wouldn't have come on our show?

Mr. CRUMB: I don't enjoy doing this really. I don't--this isn't my thing.

You know, I'm not a guy that likes to get up there in front of people, but

somehow I--people keep dragging me up and pushing me in front of the public.

I don't know. I just want to stay in my room and draw comics and

occasionally, you know, have friends over or, you know--it's not--I don't want

to be doing this kind of stuff that much. It's nerve-wracking. Takes it out

of me.

GROSS: Well, you're too interesting for us to let you just stay in your room

all the time.

Mr. CRUMB: Right. I'm going back to my room now. I'm never coming out

again. This is the last interview I'm ever doing.

GROSS: You don't mean that.

Mr. CRUMB: I do. I mean it. I mean it this time. This time I really mean

it.

GROSS: Well...

Mr. CRUMB: This is it. I quit the music business. I don't play music in

public anymore. It was too nerve-wracking.

GROSS: Wait. There's that recording from 2003. That's just a couple years

ago.

Mr. CRUMB: Yeah, it's the last time I did it.

GROSS: Really?

Mr. CRUMB: Last time. Never do it again.

GROSS: Well, do you have stage fright?

Mr. CRUMB: I do. I have stage fright, I get real nervous. Oh, awful.

I--being in the music business like that and performing on stage was never a

happy, fun thing for me. Problem is I liked playing the music so I would play

music with these guys. Because I had some kind of name, some kind of fame

they'd say, `Oh, we can get gigs,' you know, and they could sell tickets and

da-da-da-da. So I got sucked into performing publicly and, you know, I liked

these guys, I wanted to help them and, you know, they're my buddies and

they--you know. So that's the way it goes. But I--finally I had to quit, and

my worst nightmare came true. Of course, they were deeply hurt when I quit.

When I quit The Cheap Suit Serenaders, they took it very personally and were

deeply hurt no matter how much I tried to explain it to them that I--not them,

I like the music, but I just can't do it anymore in public. And then I got

sucked into playing with that French band, and again I liked those guys, I

love the music, old-time French music, but--and the gigs were, oh, just

nerve-wracking and pulled me away from my work, and I just wanted to sit in my

room and draw. And I had to go out and perform and, you know, go on stage and

da-da-da and...

GROSS: Well...

Mr. CRUMB: Phew. Whoa.

GROSS: Listen...

Mr. CRUMB: And when I quit that band, it was the same thing.

GROSS: I know being interviewed isn't your favorite sport, so...

Mr. CRUMB: No. Well...

GROSS: ...thank you so much for doing this. I really appreciate it a lot.

Thank you.

Mr. CRUMB: OK. All right.

GROSS: R. Crumb. His new book is called "The R. Crumb Handbook." It

includes many of his comics as well as a CD of his music.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross. We're closing with the title track from the 1993

album "Singing in the Bathtub" by R. Crumb & The Cheap Suit Serenaders.

(Soundbite of "Singing in the Bathtub")

Mr. CRUMB & THE CHEAP SUIT SERENADERS: (Singing) Singing in the bathtub,

sitting all alone. Tearing out a tonsil just like a baritone. Never take a

shower. It's an awful pain. Singing in the shower's like singing in the

rain. Oh there is dirt to be abolished, but don't forget one thing. While

the body's washed and polished, sing, brother, sing. You can yodel opera even

when you scrub. (Foreign language sung). Everybody's happy while singing in

the tub. I'm forever blowing bubbles, pretty bubbles in the air. Oh, a ring

around the bathtub isn't so nice to see. But a ring around the bathtub is a

rainbow to me. Reaching for a towel, ready for a rub. Everybody's happy

while singing in the tub.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.