Hall Of Famer: Randy Newman Makes The Cut

Known for such hits as "Real Emotional Girl", singer-songwriter, composer, arranger and pianist Randy Newman is on his way to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Newman, a 40-year veteran of the music business, talked to Fresh Air in 1998 and 2004 about his life and work.

Other segments from the episode on December 14, 2012

Transcript

December 14, 2012

Guests: Randy Newman â Ravi Shankar

DAVID BIANCULLI, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli, editor of the website TV Worth Watching, sitting in for Terry Gross. This week, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame announced its latest round of inductees, and among them is singer/songwriter Randy Newman. You have to have 25 years as an artist to qualify for the Hall of Fame, but Newman has clocked a lot more time than that.

His first album, "Randy Newman," was released in 1968, 44 years ago. After writing such songs as "Sail Away" and "Short People," he shifted his focus to Hollywood, where he's enjoyed a prolific and successful career writing scores for live-action and animated films from "Ragtime" to "Toy Story." He won an Oscar for Best Original Song, which he wrote for "Monsters, Inc."

Most recently, he's been revisiting his catalog in a series of American songbook solo albums, just Newman and his piano. Here's his new recording of one of his sharpest satirical songs, "Political Science." Newman wrote it in 1972, yet 40 years later it's anything but dated.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "POLITICAL SCIENCE")

RANDY NEWMAN: (Singing) No one likes us. I don't know why. We may not be perfect, but heaven knows we try. But all around even our old friends put us down. Let's rock the big one, see what happens. We give them money, but are they grateful? No, they're spiteful, and they're hateful. They don't respect us. So let's surprise them. We'll drop the big one and polarize them.

(Singing) Asia's crowded, and Europe's too old. Africa's far too hot, and Canada's too cold. South America stole our name. Let's drop the big one. There'll be no one left to blame us. We'll save our strength. Don't want to hurt no kangaroo. We'll build an all-American amusement park there. They've got surfing, too.

(Singing) Boom goes London, and boom Paris, no room for you and no room for me. In every city the whole world round, we'll just be another American town. Oh, how peaceful it'll be. We'll set everybody free. You'll wear a Japanese kimono, babe, and there'll be Italian shoes for me.

(Singing) They all hate us anyhow. So let's drop the big one now. Let's drop the big one now.

BIANCULLI: That's Randy Newman, performing "Political Science" from his American songbook album, volume one. Today we'll hear two of Randy Newman's appearances on FRESH AIR, beginning with an interview Terry did with him in 1992, when he was seated at a piano in our studio.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: Have you developed a separate sound for accompanying yourself at the piano than you use if you were just sitting at the piano alone to play? Do you think of yourself as having a sound that you use when you're singing?

NEWMAN: A pianistic sound?

GROSS: Yeah, I mean I think of you as having one, but I couldn't explain it.

NEWMAN: I don't think of it. But I probably just adjust to what I'm doing, yeah. I have a, you know, a style of playing, I think, that I can tell it's me if only because I can't keep time.

GROSS: Is there a certain kind of left hand that you think of as you or something?

NEWMAN: Oh, you know, my son does this imitation of me. You know, he goes - it's this...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

NEWMAN: I'm very fond of shuffles. I have been all my life. It seems to be my natural mode of expression. My mother was from New Orleans. I don't know whether that has anything to do with it, but...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

NEWMAN: (Singing) Blue Monday, I hate blue Monday, got to work like a slave all day.

I mean, that's the stuff I love, and people don't tend to like shuffles that much, you know, and drummers hate them. But I've written more than I should have, and so maybe there's something to my left hand.

GROSS: So when you first got access to a piano, when you were trying to do things that you heard...

NEWMAN: As a kid?

GROSS: Yeah, as a kid.

NEWMAN: I never tried to do things I heard. I just played out of the little, you know...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

NEWMAN: You know, the Thompson(ph) from a wigwam book. And the party...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

NEWMAN: That was getting complicated there. But I never - you know, there was much in my family, and I remember when I was about six, all of a sudden there was like a piano in my room, you know, just in case I was Mozart.

(LAUGHTER)

NEWMAN: I think they wanted to have this thing loom - it was an upright, Hoffman(ph) upright, looming over me. My dad was a doctor, but he loved show business. Before he went in the Army, he went on that Hollywood caravan tour one of my uncles conducted during the war, and he was a doctor on that, and I guess he never got over it.

I mean, I think he wanted me to be a musician, though he never admitted it. I mean, what was the piano doing there? I didn't know what to do with it.

GROSS: Right. So if you started off playing, you know, piano for beginning type books, how did you start to learn rock 'n' roll? Did you just pick it up from records? Could you...?

NEWMAN: I think I did when I was, you know, started 15, 16, a friend of mine suggested, you know, why don't you try and write some songs. His father was in the record business. So I did. And a publisher signed me up. But it isn't like - you'll hear stories of a lot of guys listen to records, they just, it did something to them, it flicked some kind of switch in them where they'd listen and copy the riffs on everything.

I never did it. I never - I was pushed kicking and screaming the whole way, it seems like, into music in some kind of way. Even when I was in college, people would be all - they'd say, oh, did you hear Shostakovich's 11th symphony, or I don't know what it was then, about 11 then. And I, you know, I hadn't heard it. But I was better than everybody at composition classes and stuff like that, worse at, you know, sight-singing and things like that.

But I was like, I was good at it. I had a talent for it.

GROSS: What was the first kind of stuff you started writing at the piano for yourself?

NEWMAN: The first thing I wrote was like a summer song. I was 16, 17.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

NEWMAN: (Singing) They tell me it's summer, but I know it's a lie because summer's for laughing, all I do is cry.

Things like that, you know, not really bad but just vapid.

GROSS: Can I ask you to do a chorus of "Lonely at the Top"?

NEWMAN: Sure.

GROSS: I just think that's one of your really kind of fun songs.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "LONELY AT THE TOP")

NEWMAN: (Singing) I've been around the world. I've had my pick of any girl. You'd think I'd be happy, but I'm not. Everybody knows my name. But it's just a crazy game. Oh, it's lonely at the top.

You know what I was noticing, since you're sitting right here, and I'm singing, how hard it must have been, unless you're an actor in movies. You know, I was trying to look at you and sing. It's murder.

(LAUGHTER)

NEWMAN: It would be murder to listen, too, you know.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

NEWMAN: (Singing) I love you. I'll always love you.

GROSS: It's really embarrassing to...

NEWMAN: I couldn't do it.

GROSS: Yeah, right.

NEWMAN: Yeah, you don't know what to do. I don't know what to do.

GROSS: Exactly, exactly. So are you averting your eyes?

NEWMAN: Oh very much so. I'm afraid. As a matter of fact, I'm glad I can't see audiences. You know, when you do TV, they're lit up. So, you know, you're playing along on Letterman or "Saturday Night Live," and you can see the people, and, you know, (unintelligible) talking to each other. I'm afraid to look.

GROSS: I remember from the last interview we did that you wrote that for Frank Sinatra.

NEWMAN: Yeah, I did. I thought it really would have been kind of hip if he did that.

GROSS: Yeah.

(LAUGHTER)

NEWMAN: And I played it for Streisand, but she said, well, people would believe it, you know, if she sung that. Maybe she's right.

GROSS: Did people believe it about you? Did they think that you're singing (unintelligible)...?

NEWMAN: It depends, some towns. You know, I used to play in Philadelphia, strangely enough, where we are, and they wouldn't laugh. They'd think I was, even if there were 12 people in the audience, you know, at a club.

BIANCULLI: Randy Newman at the piano, recorded in 1992. We'll hear another interview Terry recorded with him after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

BIANCULLI: Randy Newman will be inducted next April into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, an honor that many say is long overdue. After all, he released his career-encompassing CD compilation "Guilty: 30 Years of Randy Newman," 14 years ago. Terry Gross spoke with him in 1999 about that CD compilation.

GROSS: What was your image of a songwriter back then? This was kind of a transitional period in the early '60s. You know, you're past Tin Pan Alley, you're kind of in the end of the (unintelligible) era, and right at the kind of dawn of the big - of the period where bands are going to be writing their own songs.

NEWMAN: The image I had was that ancient motion picture image of Tin Pan Alley and two guys hammering it out, and it was also of Carole King and Gerry Goffin and Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil and the people who were very successful contemporaneously with my attempts to write songs for people.

GROSS: I want to get to another track from the third CD on your fourth CD box set, and this is the CD of demos and other mostly previously unreleased material. This is a song called "Love is Blind," which is - you know, just as the first song that we heard, "Golden Grid Iron Boy," is very out-of-character for you, this kind of cheerful - well, not cheerful, not cheerful but an upbeat football song.

NEWMAN: It's a generic lyric. You know, that's what it is.

GROSS: Exactly, right. You say in the notes that you wrote it when you were 18.

NEWMAN: Yeah.

GROSS: So you were 18 and already writing that love is bitter, love is hopeless, love is blind. It leads me to think that you already had a sense of yourself as writing more dark and cynical songs than your average songwriter.

NEWMAN: Well, there are some pretty lugubrious love songs. You know, I mean, a lot of them are pretty bleak, you know, you stop loving her today and a lot of country things. But I was a pretty down cat, I guess.

(LAUGHTER)

NEWMAN: I don't know.

GROSS: Well, let's hear this song, "Love is Blind," written in about 1962. The recording we'll hear is 1968, and this is from Randy Newman's box set "Guilty: 30 Years of Randy Newman."

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "LOVE IS BLIND")

NEWMAN: (Singing) They say that love's a sweet thing, and for lovers the sun will always shine. But in spite of what they say, I think of love this way: Love is bitter; love is hopeless; love is blind.

(Singing) I learned the hard and lonely way that love can't last through the years. I spent a thousand empty yesterdays hiding behind a veil of tears. Now poets may write about love, and wise men may sing its praise. But I'll always remember, as I go through the empty days: Love is bitter; love is hopeless; love is blind.

GROSS: "Love is Blind," one of the demos on Randy Newman's box set "Guilty." What were you saying there?

NEWMAN: I was laughing at the ending. You know, I was just sort of aimless wandering, you know what I mean. Motion-picture movie business, we call it grazing.

(LAUGHTER)

NEWMAN: You know, it's just like I was waiting to end it. I know where I should have gone, but I didn't go there. It made me laugh.

GROSS: Well, that was a demo. Did you ever record it other than that for yourself?

NEWMAN: No, I never thought enough of it.

GROSS: Well, I like it a lot. Why don't you like it?

NEWMAN: Yeah, I do, too. Oh, veil of tears you know, things like that.

GROSS: Well sure.

NEWMAN: I mean, yeah, sure, but I grew to not be able to stand that stuff coming from myself. I mean, I'll listen to records and love them, and they'll have lyrics like that in them, but I can't do it. You know, it's like if you know better, don't do it.

GROSS: I just figured I could put kind of like little quotes around the veil of tears and say oh, that's a little tip of the hat to the genre.

(LAUGHTER)

NEWMAN: Well, that's being too kind. I mean, it's just - you know, none of it was heartfelt in that, you know, I don't think I've been in love with anybody. You know, I certainly didn't have all these sophisticated, you know, it's bitter and blind at 18, you know. So I mean I hope not. I couldn't - I just didn't think of recording it.

I like it, too. I like everywhere it goes. The harmonic, you know, structure of it, I mean, I've - it sounds like me. It's what I do today.

BIANCULLI: We're listening back to Terry's 1999 interview with Randy Newman. During the interview, she also asked him about his song "Maybe I'm Doing it Wrong," a waltz about sex not living up to expectations.

GROSS: So many pop songs are supposed to be sung in the voice of the seducer who's bragging about how good a lover he is.

NEWMAN: Yeah.

GROSS: Did you intend this to subvert that kind of song?

NEWMAN: Yeah, and it's really a great idea because it's a widespread thing. You know, people don't necessarily talk about it. I mean, you have no idea from knowing a person, my experience is, at least, what they're like sexually, or you can't even guess at that, that and money. You know, you can try and borrow $5 from someone you've known for 30 years, and they won't give it to you.

And it's a complete unknown. And I really like - this song is short, but I always thought it was a great idea for a song, and like I'd wished I'd done more, but I couldn't think of what more to do.

GROSS: Let's hear it. This is "Maybe I'm Doing it Wrong."

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "MAYBE I'M DOING IT WRONG")

NEWMAN: (Singing) Maybe I'm doing it wrong. Maybe I'm doing it wrong. It just don't move me the way that it should. Maybe I'm doing it wrong. There ain't no book you can read. There ain't nobody to tell you. But I don't think I'm getting what everybody's getting. Maybe I'm doing it wrong.

(Singing) Sometimes I throw off a good one. At least I think it is, no I know it is. I shouldn't be thinking at all. I shouldn't be thinking at all. Maybe I'm doing it wrong. Maybe I'm doing it wrong. It just don't move me the way that it should. Maybe I'm doing it wrong.

GROSS: Why did you write that song as a waltz?

NEWMAN: I don't know. It just came out that way. Almost every song I've written has had words and music sort of come at the same time. But no, usually the music comes a little first. So I probably was just clumping along like that, and it just - I didn't do it for any artistic reason, though I'd be happy to take credit for any sort of Viennese reason that you'd like to give me.

GROSS: Oh, well, thanks for the invitation.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: I have a reason I'd like to give you.

NEWMAN: Yeah.

GROSS: This song is about kind of frustration in sexuality, but the waltz has such a nice lilt, such an easy lilt, that it's a nice contrast.

(SOUNDBITE OF HUMMING)

(LAUGHTER)

NEWMAN: It does. You know, it, yeah, it's sort of in one. Yeah, it could be. It might be also I love the record called...

(Singing) If you got to make a fool of somebody...

I don't know which came first, but I mean, I wanted, maybe I wanted to write something like that. It's an - this is an instance I hear - I listen to the audience where sometimes, Harry Nilsson once told me, I asked him, you know, it was a constant thing with him not performing, why he didn't perform.

And one time - it was mainly I think because he was frightened of it, I think, but I don't know. But he said once it was because he was worried it would hurt his work, that the audience reaction would be, like, throw him off because he wouldn't know his good stuff.

And it's a very small thing that you can isolate it as a writer. I mean, the audience will react to some things, like sometimes I'll throw off a good one. Like I probably could have done better there, you know, but they laughed at it. I knew they liked it. So I left it alone.

GROSS: Randy Newman, thank you very much for talking with us.

NEWMAN: Great pleasure, as always.

BIANCULLI: Randy Newman, speaking to Terry Gross in 1999. He'll be inducted in April into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. I'm David Bianculli, and this is FRESH AIR.

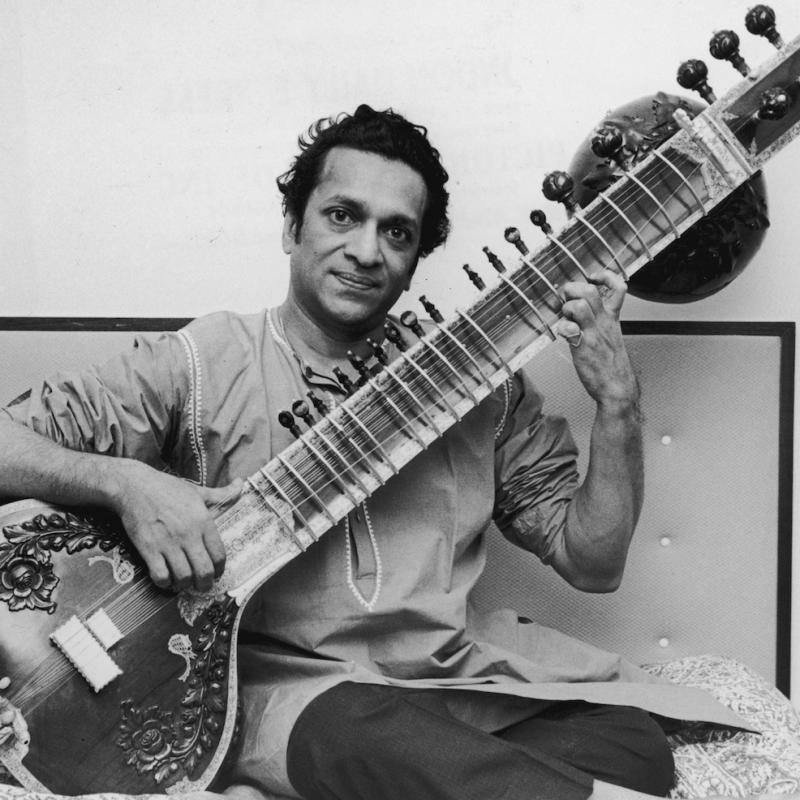

DAVID BIANCULLI, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli sitting in for Terry Gross. Ravi Shankar, who popularized the sitar and Indian music in America, died this week at the age of 92. He befriended the Beatles, gave George Harrison sitar lessons, and inspired Harrison to launch the first superstar benefit concert, 1971's the Concert for Bangladesh.

That's when Ravi Shankar, tuning up before his performance, responded to the polite but clueless support of the U.S. audience. His ad lib was good-humored but pointed.

(SOUNDBITE OF "THE CONCERT FOR BANGLADESH")

(APPLAUSE)

RAVI SHANKAR: Thank you. If you appreciate the tuning so much, I hope you'll enjoy the playing more.

(APPLAUSE)

BIANCULLI: The Concert for Bangladesh was the first time many young Americans heard Indian music in its unadulterated form. After those musicians tuned up, this is what the audience heard.

(SOUNDBITE OF RAGA MUSIC)

BIANCULLI: In his lifetime, Ravi Shankar also influenced the work of John Coltrane, Philip Glass and many other Western musicians. The week before he died, he was informed he would be honored with a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award next February. His children include Anoushka Shankar, who also is an accomplished sitar player, and singer Norah Jones.

Ravi Shankar spoke with Terry Gross in 1999. She asked him about his relationship with George Harrison.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED INTERVIEW)

TERRY GROSS, HOST: Now, you've been very close to George Harrison. You've described him as being almost like a son. And he's described you as being almost like a father. You met him in 1966, and this was a period when all the Beatles seemed to be searching for some kind of...

SHANKAR: Exactly.

GROSS: ...spiritual help. What did you make of the Beatles when you met them? They were in this period of a kind of spiritual search. Did you consider that search to be an authentic search? Or do you think - did you feel that they were very kind of confused about what they were looking for?

SHANKAR: It was exactly what you are saying. They were confused and they were searching. But to tell you truth, when I met them, I didn't know, almost didn't know them or know anything about them, because I had just vaguely heard that it's a popular group. And it was in a party that all the four were there, but it was only George that interested me from the very beginning because of his being so inquisitive and asking the questions about music and relation to the religion and the spiritual aspect of it and the whole thing. And that's how we came close together and he started having some lessons.

GROSS: What did you think of the solo he played on "Norwegian Wood"?

SHANKAR: I never heard it before. And it was only much later on, my nephew and nieces, they played it for me and I thought it was terrible, in the sense - in the sound that was produced on the sitar. The song was nice. I liked the song very much but it was a peculiar sound. It didn't sound like sitar even. So he had had little lesson from a person in London who's a student of a student of mine, who is to be in London at that time. And I told him frankly that it's fine. People like it and you are happy but I didn't find it interesting enough because the very sound of sitar, it is something which we have developed since last 750 years. And - but I - he understood and that's why he wanted to learn.

GROSS: You started playing with Western musicians. And I think really you were the first Indian musician to start playing with Western jazz musicians and rock musicians and classical musicians. Why did you want to do that?

SHANKAR: As Sale Lucien (ph) said to his son, correction, I would like to correct you...

GROSS: OK. Please.

(LAUGHTER)

SHANKAR: I didn't start with rock or jazz musicians. It was just my great dear friend whom I miss very much who is no more, Yehudi Menuhin, Lord Yehudi Menuhin. We got very friendly from the year 1952. And when I came to Europe and started performing, we cut three albums in those days, known as "West Meets East." And then I did many other things later on, of course. My student George Harrison, who is like my son, and a great friend of mine, whom I taught sitar initially but later on he was so interested he composed a lot of songs being influenced by our Indian music and Indian spiritual and religious teachings, things like that. And I've done a lot of experimentations, which I don't like to call fusion or trying to mix Indian music or Western music like a cocktail to make it interesting. Genuinely what I wanted to do is have the base as pure as possible Indian music within the framework of raga and tala, and use non-Indian musicians, non-Indian instruments for a special sound, for the range, for the volume, for the colors and all that. And I think some of them came out nice. Of course I was very much criticized also for it...

GROSS: Criticized in India.

SHANKAR: Especially from India, and our musicians. But nevertheless, now things have changed. Things that I have done 30 years ago, 40 years ago, are being appreciated now, which makes me happy.

GROSS: When you were studying with your guru, he told you that music is sacred and should be kept that way when you perform. And he told you that this applies not only to the performer but also to the atmosphere that he's playing in. In other words, there should be a sense of decorum shown by the audience. And you write in your book that there were times when you didn't feel that kind of sacred sense around the music, when the audience would be drinking or talking too much or the place was just too messy.

SHANKAR: Exactly. Exactly.

GROSS: And you wouldn't even play, you'd leave.

SHANKAR: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: So what was it like for...

SHANKAR: So many times I stopped and I told them I won't play unless they move away all the drinking things and they sit properly and they have a platform for me, not just spread a rug on the floor. This was with some harajas and aristocrats in India. I always fought with them. But later on I had to fight with my young friends, whom I loved very much, in the mid-'60s onward, the hippies. You know, almost same thing, because George was my student and I was the guru of George, it become like a cult sort of thing, you know. Along with the music, they took me as a guru, yeah. What happened, they came to my concert with the same spirit, being stoned, absolutely high on drugs, LSD or whatever, shouting, shrieking and misbehaving, doing all these sort of things that they should not do. So I had to tell them that, look, when you go to listen to Bach or Beethoven or Mozart, do behave like that? I'm sure they don't go to listen to these people.

GROSS: No, I was going to point that out. Yeah.

(LAUGHTER)

SHANKAR: First of all. But even if they did, they wouldn't behave like that. So many times I had to walk out with the sitar and I had to explain them, please try to listen with a pure mind, because I assure you that our music has that power, that it can make you feel high. But if you are already gone to - so spacey, you know, what you hear is not the real thing. And...

GROSS: But you played, you played at the Monterey Pop Festival. You played at Woodstock. And, you know, certainly at Woodstock especially, that sense of a kind of respect and sense of, you know, sacredness of music...

SHANKAR: Well, I have written about it, and I'm sure I have spoken about that a number of times. Monterey was something which I liked because it was still new, fresh. And there was some - in spite of the drugs and everything, when these young girls and boys, they showed these two fingers like that, like a V, and said peace and love and offered you a flower, there was some innocence. There was some beauty which touched me so much. But Woodstock was a time which was almost two, three years later. And believe me, by then I thought that this thing is not going to live anymore because it was far gone. Music was just an incidental music to them. They were having fun. It was a fun place, picnic party. They were all stoned. It was raining. It was in mud. And as I said in my book, it reminded me of these water buffaloes we see in India who are, you know, they feel very hot and they sit there, get so - so dirty, but they enjoy it. So I mean that was the thing I felt. But because it was a contractual thing, I couldn't get out of it. I had to go through it. But I was very unhappy.

GROSS: Now, I know that you don't like psychedelic drugs and don't really approve of them. The funny thing is, there was a period in the '60s when if you heard the sitar in America, chances were it had some kind of psychedelic connotation to it. It was in a movie about psychedelic drugs...

SHANKAR: Exactly.

GROSS: ...or an advertisement for a place that wanted to have a kind of psychedelic image. How did that make you feel?

SHANKAR: Terrible.

(LAUGHTER)

SHANKAR: Because all that was so bizarre, I tell you. When I went to Haight-Ashbury and saw what is happening, I couldn't believe it, you know, and all in the name of tantra, mantra, yoga and everything. It got mixed up. And that's why they had to have a sitar twanging whenever they showed a orgy scene or anything like that.

GROSS: Exactly. (Laughing)

SHANKAR: And used to make me so, so unhappy, I tell you. So it was difficult for me. Now I'm used to it. It doesn't matter to me. Whatever you do is your business. As long as you do it yourself well, as long as you are happy and you can make others happy, I think that's fine. I can really, I have changed quite a lot in my way of appreciation or being angry at something. All that is no more there.

BIANCULLI: Ravi Shankar speaking with Terry Gross in 1999. He died this week at age 92.

DAVID BIANCULLI, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm TV critic David Bianculli. Tonight on PBS, "Great Performances" presents a documentary about the making of a Beatles TV special from 1967, then shows a restored version of that special, which is called "Magical Mystery Tour." It has the music from the U.S. album of the same name, but it's not the album. It's a musical comedy fantasy about the Beatles and a busload of tourists taking a trip to unknown destinations.

PAUL MCCARTNEY: It wasn't the kind of thing we could do a disclaimer before and say, ladies and gentlemen, what you're about to see is the product of our imaginations, and believe me, at this point they're quite vivid.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

BIANCULLI: That's Paul McCartney, talking about the original broadcast of the "Magical Mystery Tour" TV special in England. It was written and produced in 1967, which was an incredibly fertile period for the Beatles. "Strawberry Fields Forever" came out that year, and "Penny Lane," and the "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band" album, which was followed, a month later, by the live TV premiere of "All You Need is Love," broadcast globally. The Beatles, it seemed, could do no wrong. And then they did "Magical Mystery Tour," which was televised by the BBC the day after Christmas - on Boxing Day - as a holiday special. A quarter of the British population watched it - and many of those hated it.

Back then, the 53-minute program was filmed in color but wasn't broadcast that way. Imagine the "Sgt. Pepper" cover in black and white and you can imagine how much was lost in the translation. Reception to the TV special was so poor that the show wasn't even picked up in the United States - just the soundtrack. Eventually the special was syndicated to some local TV stations and toured the college film circuit along with "Reefer Madness." That's when I first saw it. But on a national level, "Magical Mystery Tour" has never been televised in the United States - until now.

Friday night on PBS - as always, check local listings - "Great Performances" is presenting "Magical Mystery Tour," preceded by a new one-hour companion documentary called "Magical Mystery Tour Revisited." This may be the first case on record in which a documentary about a film is longer than the film itself. But it's worth it.

BIANCULLI: The documentary, produced by Jonathan Clyde of Apple Films and directed by Francis Hanly, is wonderfully thorough. It explains how the idea for "Magical Mystery Tour" came about and how Paul originally drew the concept as a pie chart, then shows the chart. It covers the origins of each number written specifically for the show from the title song and "The Fool on the Hill" to "I Am the Walrus" and "Your Mother Should Know."

It presents lots of outtakes and new interviews with McCartney and Ringo Starr, as well as Martin Scorsese, Terry Gilliam, and Peter Fonda. It also includes a vintage interview with George Harrison, whose assessment of the 1967 TV special is as unfiltered as the program itself.

(SOUNDBITE OF DOCUMENTARY, "MAGICAL MYSTERY TOUR REVISITED")

GEORGE HARRISON: They hated it, at least the people who wrote in the newspaper hated it. You know, they - don't forget that with all the success we had, every time something came out, a new record or whatever, they'd all try and slam it so that, you know, once they've built you up that high, you know, all they can do is knock you back down again. I mean, that's what happens. That's life. And so they really didn't like it. But it's understandable too because it wasn't a brilliant, scripted thing that was executed well. It was like a little home movie, really, an elaborate home movie.

BIANCULLI: It's a fine documentary. Better, to be honest, than "Magical Mystery Tour" itself. But "Magical Mystery Tour" is so much fun to watch if you're a Beatles fan, that it serves up one joy after another. John serving shovels of spaghetti as a waiter in a dream sequence. John and George in a strip club watching the house band singing a song called "Death Cab for Cutie" which, incidentally, inspired the name of a much more recent rock band.

And the closing production number, "Your Mother Should Know" which has the Beatles in white suits dancing in unison down a giant staircase. In addition to the PBS double feature, "Magical Mystery Tour" also now available as a deluxe box set from Apple. It includes Blu-ray and DVD versions of the original special, a vastly shortened version of the documentary, and lots of extras including outtakes and complete scenes that were cut out of the program before its 1967 premiere.

These extras are every bit as entertaining as "Magical Mystery Tour," and one segment is a minor revelation: singer-songwriter Ivor Cutler, seated at an ornate white organ in the middle of an English countryside, performing his composition "I'm Going in a Field." It must have been hypnotically bizarre then. It's hypnotically bizarre now.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG "I'M GOING IN A FIELD")

IVOR CUTLER: (Singing) I'm going in a field. I'm going in a field. I'm going in a field to lie down. I'll lie...

BIANCULLI: It's no secret that I'm almost ridiculous in my enthusiasm for the Beatles. But for me, all this new "Magical Mystery Tour material" - the restored TV special, the documentary, the boxed set - is like a perfectly timed holiday gift. The boxed set is expensive but the Great Performances double feature is free. All you need is a TV set.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "MAGICAL MYSTERY TOUR")

THE BEATLES: (Singing) Roll on up for the magical mystery tour. Step right this way. Roll up. Roll up for the mystery tour. Roll up. And that's an invitation. Roll up for the mystery tour. Make a reservation. Roll on up for the mystery tour. The magical mystery tour is waiting to take you away. Waiting to take you away. Roll up. Roll up for the mystery tour. Roll up. Roll up for the mystery tour. Roll up...

DAVID BIANCULLI, HOST: "Zero Dark Thirty" is the new film about the hunt for Osama bin Laden. It's from Kathryn Bigelow, director of 2008's "The Hurt Locker." The film opens December 19th but already has generated controversy over the depiction of the CIA's use of torture. Film critic David Edelstein has this review.

DAVID EDELSTEIN, BYLINE: Kathryn Bigelow's kill bin Laden thriller "Zero Dark Thirty" is cool, brisk, and packed with impressively real-sounding intelligence jargon. It presents itself as a work of journalism - just the facts, ma'am - but there's no doubting its perspective. It's the story of America's brilliant righteous revenge.

The prologue is a black screen with sounds of 9/11, a hubbub of confusion, and then, most terribly, the voice of a woman crying out to a 911 operator who tries vainly to assure her she'll be OK. The recording is genuine. What follows takes place two years later at an off-the-grid CIA black site. An al-Qaida prisoner is strung up and waterboarded by a big bearded agent named Dan, played by Jason Clarke.

It's brutal and ugly and the film's protagonist, a newly transferred CIA operative named Maya, played by Jessica Chastain, quietly registers horror. But after that 9/11 prologue the prisoner's treatment doesn't seem wrong. More important, the information Dan extracts from that man after more attempts and a bit of subterfuge, will lead over the next decade to bin Laden's courier, who will lead to bin Laden.

This week I've been caught up in controversy over a magazine review I wrote of "Zero Dark Thirty," which I called both phenomenal, the best movie of the year, and morally problematic. I've been attacked from both sides as either too knee-jerk liberal about torture or too tolerant of pro-torture propaganda. But the jury is out on whether the courier intel came from torture.

Senator Dianne Feinstein and author Peter Bergen say no. Author Mark Bowden and "Zero Dark Thirty" screenwriter Mark Boal's CIA sources say yes. For her part, Kathryn Bigelow has never been a filmmaker with a strong moral point of view. "The Hurt Locker" begins with a quote from iconoclastic journalist Chris Hedges, likening war to an addictive drug. Bigelow identifies with adrenaline addicts, most often men but here a woman - although a woman whose role in the story is to be more macho than the men.

She has to bully colleagues publicly humiliated after the failure of WMD Iraq intelligence to take risks now in the name of catching bin Laden. She's the one who tells Navy SEALs in an airplane hangar the object of their mission.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "ZERO DARK THIRTY")

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #1: (as character) You'll notice the stealth panels similar to what we use on the B2. The rotors have been muffled with decibel killers. It's slower than a Black Hawk. It lacks the offense and the stability. But it can hide.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #2: (as character) So, uh, excuse me. What do we need this for in Libya? I mean, Gadhafi's anti-air is virtually non-existent.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #1: Maya, you want to brief them?

JESSICA CHASTAIN: (as Maya) There are two narratives about the location of Osama bin Laden. The one that you're most familiar with is that UBL is hiding in a cave in the tribal areas, that he's surrounded by a large contingent of loyal fighters. But that narrative is pre-9/11 understanding of UBL.

The second narrative is that he's living in a city. Living in a city with multiple points of egress and entry, access to communications so that he can keep in touch with the organization. You can't run a global network of interconnected cells from a cave.

EDELSTEIN: There's been speculation Maya was inspired by the same covert CIA agent as Claire Danes' bipolar Carrie in "Homeland," but the parts and actresses could hardly be more different. Chastain is stripped down to pure will; you know what she's feeling by the tension in her body. Killing bin Laden has become a religious quest, a counter-jihad. And she's frustrated that so much of her job comes down to pitching, as in Hollywood. There's always another professionally skeptical CIA bureaucrat to be sold on the probable whereabouts of the courier. Then he'll have to sell his superior, who'll have to sell the commander in chief.

Bigelow makes those pitches hum. She's a wizard at alternating fast-moving, streaky shots with shots that suddenly give you your bearings, so you're always one step behind, rushing to catch up. In the incredibly tense climax, the SEALs' night-vision goggles turn the compound green. The camera follows them through doors and up stairs, the only sound the bouncing of equipment, the bleating of sheep, and then, after the firing begins, the sobbing of children.

The carnage is quick and conclusive. Bigelow doesn't serve up a Hollywood shootout, and the way the SEALs pump extra bullets into prone bodies - among them bin Laden's - is disturbing. But for all the supposed neutrality and the sad, ambiguous final shot, the ending is happy. We got him.

After 9/11, Dick Cheney said that to fight terrorists America had to embrace the dark side, and Kathryn Bigelow has given that dark side a woman's blessing. "Zero Dark Thirty" is mercilessly gripping, a great thriller. But it's not a great work of art. To be divided about it is not to be wishy-washy. It's to say, I'm blown away by this, but given the larger implications of this event, is that enough?

BIANCULLI: David Edelstein is film critic for New York magazine.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.