Guests

Host

Related Topics

Transcript

DAVID BIANCULLI, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli, professor of television studies at Rowan University in New Jersey, sitting in for Terry Gross. Today, we're concluding our multi-day tribute to Broadway composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim, who died last week at the age of 91. On this show, we'll be spending time with some of the people who worked with him or performed in his musicals.

One quick personal note before we start - "Company" premiered on Broadway in 1970 and was the show I saw on my first night ever in New York. I was visiting as part of a high school theater class from Florida, and "Company" blew me away so completely that it began a lifelong love of musicals in general and Stephen Sondheim in particular. After that, I traveled to New York to see as many as I could attend. I saw the original "Follies" and "Sweeney Todd" in previews and eventually took my own kids to every new Sondheim show and revival. Next year, I start taking my grandkids. And when I got the opportunity to talk to Sondheim onstage in 2018 and discuss his work in a 90-minute interview at Rutgers University, it was one of the highlights of my entire career.

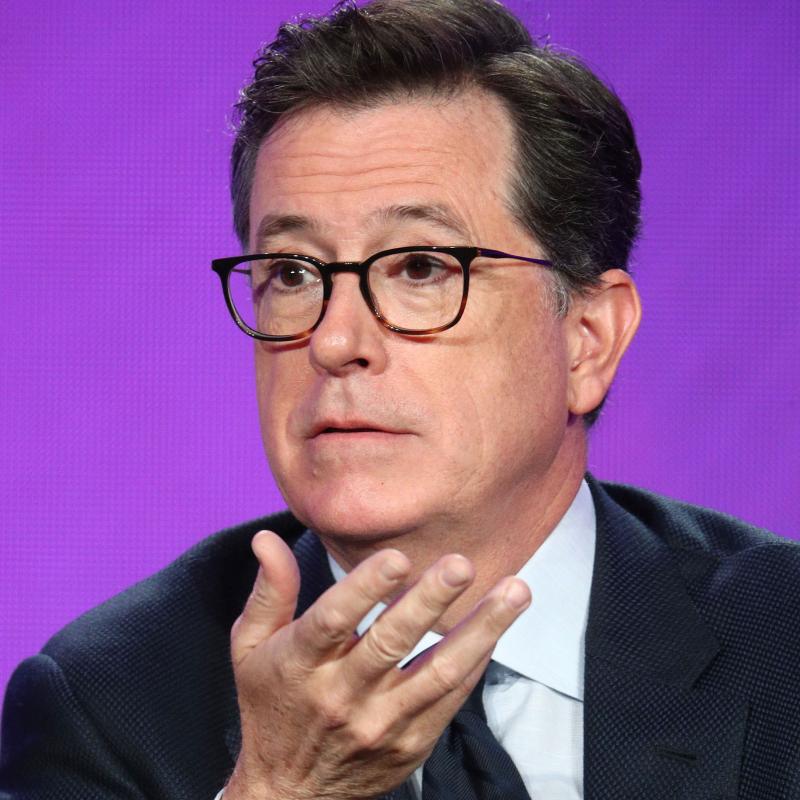

Stephen Colbert interviewed Sondheim, too, on TV back in December 2010, when Colbert was still hosting "The Colbert Report." He emerged from that interview with an unexpected bonus - a role in a "Company" revival by the New York Philharmonic. Colbert explained the sequence of events to Terry Gross on FRESH AIR in 2011.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

TERRY GROSS: So let's talk about "Company." There's a song in "Company" that you sing called "Sorry-Grateful." And it's a song about the ambivalence this character has about being married. And Neil Patrick Harris' character is the single guy in this, and all of his friends are, like, married couples, and they're actually all miserable, but they're trying to convince him he needs to get married. So he's been visiting you and your wife in this, and you've just been bickering and fighting the whole time. And then he says to you - and we'll hear what he says to you as you sing this song about the ambivalence of marriage, "Sorry-Grateful." So here is Stephen Colbert. The first line you're going to hear is Neil Patrick Harris.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "SORRY-GRATEFUL")

NEIL PATRICK HARRIS: (As Bobby) You ever sorry you got married?

STEPHEN COLBERT: (As Harry, singing) You're always sorry. You're always grateful. You're always wondering what might have been. Then she walks in. And still, you're sorry, and still, you're grateful. And still, you wonder, and still, you doubt. And she goes out. Everything's different. Nothing's changed, only maybe slightly rearranged. You're sorry-grateful, regretful-happy. Why look for answers where none occur? You always are what you always were, which has nothing to do with - all to do with her.

MARTHA PLIMPTON: (As Sarah) Harry, darling, come to bed.

COLBERT: (As Harry) Coming, darling.

GROSS: You sing with emotion and vulnerability in that song, things that you can never show on your own program, "The Colbert Report." It's such a different side of you.

COLBERT: It is. It is at that. It's what I imagined I would be doing when I went to theater school.

GROSS: Really - musicals in particular?

COLBERT: Well, just anything on - anything in theatre and musicals as part of it, I suppose. And it was such a bungee into an old dream to go do something like that 'cause I went to Northwestern University, and I went to the theater program there. And I worked very hard, and my intention was to spend my life doing theater, and that's what I thought my life would be. And it has not been, and I love what I do, but to be asked to do this and then to accept the challenge of it, I had to start taking voice lessons again because I can la-di-da my way through a lot of music, and I've done so on my show, and - but to sing Sondheim is a completely different beast.

GROSS: What's different about it?

COLBERT: Not being a music theorist, I'm not sure whether I could explain technically what's different, but there is a complexity of the note changes - like, where you're going next - in the song in Sondheim that isn't necessarily what you expect to do if you are mostly a la-di-da kind of guy.

GROSS: So how did you get the part? Who said, get Stephen Colbert 'cause it's not like you went and auditioned, right?

COLBERT: No. Well, you know, I do the show 161 days a year, and sometimes I don't know who the guest is coming up. And I looked up from my desk one day, and I saw on the grid a few days ahead of me, it said Stephen Sondheim. And I was with my booker, and I said, Stephen Sondheim. And she goes, do you not want Stephen Sondheim? I didn't know. A lot of people here weren't sure whether you'd want Stephen Sondheim. I said, God, do I want Stephen Sondheim.

I can't - because people don't know this about me, that I really like musical theater. And I think of myself as an actor and a theater person even though I've done no theater in 20 years. And people don't perceive what I do as acting, but I still do. And the canon of Stephen Sondheim is devastatingly beautiful to me, and I was so thrilled to have him on the show, so I did something I never do with my guests. I did research.

GROSS: (Laughter).

COLBERT: I actually put effort into Stephen Sondheim 'cause I knew it wouldn't be an easy interview because you never see him being interviewed. And I assumed he doesn't like it or something. And one of my writers and I worked on a little parody of "Send In The Clowns," and one of the things - I have to stay in character. Even though I like him, I just have to try to stay in character. It was very hard for me 'cause I didn't want to go in attacking Stephen Sondheim or really even be that ignorant about Stephen Sondheim, which is another sort of tactic on the show. I can either sort of be hostile toward my guests, or I can be ignorant of what they know and care about. And it was hard for me to do that with him because I care so much about him and - or his work, that is. And so...

GROSS: You know what, before you go any further, we have that clip right here. So...

COLBERT: Oh, you do?

GROSS: Yeah, we have it right here. So before you describe it more, why don't we actually hear it? And then we can talk more about how you got the part in Stephen Sondheim's "Company." So...

COLBERT: Great.

GROSS: So here's Stephen Sondheim interviewed on "The Colbert Report." And you wrote a new ending to his most famous song in this, and let's hear how that played out.

COLBERT: Yes.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE COLBERT REPORT")

COLBERT: Maybe your biggest toe-tapper out there, the one that people know the best, is "Send In The Clowns."

STEPHEN SONDHEIM: Very slow tap.

COLBERT: Very slow tap.

SONDHEIM: It's from "A Little Night Music."

COLBERT: Yeah. It's from "A Little Night Music."

SONDHEIM: Yeah.

COLBERT: It - where were the clowns?

(LAUGHTER)

COLBERT: Because they say, where are the clowns? And we never find out where the clowns were, and it really leaves the audience hanging.

SONDHEIM: She's a lost lady. She doesn't know where they are, either.

COLBERT: Well, I found where they are. Would you like - I've got some lyrics that I'd like to perhaps finish your song.

SONDHEIM: OK.

COLBERT: (Singing) Where are the clowns? I booked them for 8. Hold on. That's them on the phone, saying they're late. Traffic was bad. The tunnel's a mess. All 12 of them came in one car. They lost my address. You just can't trust clowns. That's why they're called clowns.

(APPLAUSE)

COLBERT: So much more satisfying, isn't it? Isn't that satisfying to know where the clowns are?

SONDHEIM: Well, listen. We have three weeks left of the show on Broadway - a little longer - before it closes in January. I don't see any reason why Bernadette Peters can't sing that.

COLBERT: I'm totally ready to pitch it.

SONDHEIM: No, we need some laughs in the second act.

COLBERT: I hope - is there more? Are you going to have another book after (unintelligible)?

SONDHEIM: Yeah. The second one is going to be called "Look; I Made A Hat."

COLBERT: Well, come on and talk about that.

SONDHEIM: I'd love to.

COLBERT: I rarely fawn because I like to seem more important than my...

SONDHEIM: Fawn, fawn.

COLBERT: ...Than my guests. I would just say, I'm so happy you came here. You and me, bud, we're the loonies.

(LAUGHTER)

COLBERT: Did you know that?

SONDHEIM: Yeah. I know that line.

COLBERT: I bet you didn't know that.

SONDHEIM: (Laughter).

COLBERT: Stephen Sondheim, thank you so much.

SONDHEIM: Thank you.

(APPLAUSE)

COLBERT: The book is "Finishing The Hat."

GROSS: I love that because, like, at the end, you really genuinely tell him how much you like him. And like you say, you know, you don't usually do that on your show because you have to look superior to your guests (laughter).

COLBERT: Exactly - or feel superior, at least.

GROSS: That's right. And that's a Sondheim lyric you're quoting at the end, right?

COLBERT: It is. It's - I'm imperfectly quoting it. But that's from "Sunday In The Park With George." That's the boatman who says to George, you and me, pal, we're the loonies. Did you know that? (Singing) Bet you didn't know that.

GROSS: (Laughter).

COLBERT: And I love "Sunday In The Park With George." I saw that when I was just starting theater school. And I remember singing "Finishing A Hat" - or at least reading the lyrics to "Finishing A Hat" and other songs from "Sunday In The Park With George" to my mom to try to explain why I wanted to be an artist.

GROSS: OK. Well, look; I've interviewed Stephen Sondheim, I think, four times. And he never asked me to be in one of his musicals. So what did you do (laughter)?

COLBERT: (Laughter) Well, I mean, here's - I did nothing. I did nothing.

GROSS: What did I do wrong (laughter)?

COLBERT: And I did not realize that I was auditioning at that point. I was just - one of my writers, Peter Gwinn, worked on that song. And I was so happy that he had a good time at the interview. And I was so happy that it ended well with that parody of the song and that he took it as the valentine it was meant to be. And I thought that was it. Well, great. I did a good interview with Stephen Sondheim. You know, that's a little notch on the belt. And then we got a call that Lincoln Center was going to do "Company," and would I want to play a part in it? And my agent so wisely said, no. He doesn't have any time. And he told me later that he had already turned it down. And I said, oh, geez, James. You know what? That was the right call. That's the right call. Absolutely. Wow. That's hard to say no to. But yeah, absolutely the right call. There's no way. It's insane. I can't do it.

And then a couple of days later, I got a letter from - a hand-typed letter from Stephen Sondheim saying that he - against his instincts, he had a good time on my show and would I consider playing Harry in "Company"? And he ended the letter with the sentence, you have a perfect voice for musical theater. And I read it to my wife. And she said, boy, you have to do this. No one, let alone Stephen Sondheim, is ever going to ask you to do Sondheim. And I said, you're right. I have to do it.

BIANCULLI: Stephen Colbert speaking with Terry Gross in 2011. After a break, we'll hear from someone else who appeared in a Stephen Sondheim revival show - Lin-Manuel Miranda, composer of "Hamilton." This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF TOMMY CECIL AND BILL MAYS' "FINISHING THE HAT")

BIANCULLI: This is FRESH AIR. Lin-Manuel Miranda won the Tony Award for his first Broadway musical, "In The Heights," which was set in a Latino neighborhood in New York. His next musical, "Hamilton," was a phenomenal hit, winning 11 Tonys and a Pulitzer Prize. In 2017, Terry Gross spoke to Lin-Manuel Miranda about his theatrical experience before those hit shows and how Stephen Sondheim figured into it.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

GROSS: You got to be in a production of "Merrily We Roll Along," which is a great Sondheim musical that always needs to be revived because the original Broadway run was so very short. And so this was a city center - a New York City Center Encores production.

LIN-MANUEL MIRANDA: Correct.

GROSS: And, in fact, I want to play just a little bit of you in that. So you're playing a lyricist who works with a composer. But the composer has kind of, like, sold out. And, you know, he's just doing, like, commercial work. And the lyricist now has come to think of the composer, instead of just being his friend and collaborator, Franklin Shepard, he thinks of him now as, like, Franklin Shepard, Inc. because he's so much about...

MIRANDA: Right.

GROSS: ...Like, deals and making money. So in this scene, like, you're getting interviewed on TV. And you're just kind of pretty bitter about the whole collaboration with this composer. So here's my guest, Lin...

MIRANDA: Buzz, buzz, buzz.

GROSS: (Laughter) Yeah. Here's my guest, Lin-Manuel Miranda.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #1: (As character) Now, how do you two work together?

COLIN DONNELL: (As Frank) Oh, we work.

MIRANDA: (As Charley) Oh, may I answer that?

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #1: (As character) Please.

MIRANDA: (As Charley) How do we work together? Sure. He goes...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MIRANDA: (As Charley) And I go...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MIRANDA: (As Charley, singing) And soon, we're humming along - (humming). And that's called writing a song - (humming). Then he goes...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MIRANDA: (As Charley, singing) And I go...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MIRANDA: (As Charley, singing) And the phone goes (imitating phone ringing). And he goes mutter, mutter, mutter, mutter. Yes, Jerome. I don't know, Jerome. Mutter mutter, mutter, mutter, that's his lawyer, Jerome. Mutter, mutter, mutter mutter, do it, Jerome. Click. Sorry, Charley.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MIRANDA: (As Charley, singing) So I go...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MIRANDA: (As Charley, singing) And he goes...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MIRANDA: (As Charley, singing) And I go...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MIRANDA: (As Charley, singing) And soon, we're tapping away - (humming). (Imitating buzzer) Sorry, Charlie. (Imitating buzzer) It's the secretary (imitating buzzer) on the intercom. Yes, Ms. Bzzz (ph)? It's a messenger. Thanks, Ms. Bzzz. Will you tell them to wait? Will you order the car? Will you call up the bank? Will you wire the coast? Will you - (imitating phone ringing). Sorry, Charley. Mutter, mutter, mutter, mutter - sell the stock. Mutter - buy the rights. Mutter, mutter, mutter, mutter, mutter (imitating buzzer). Let me put you on hold (imitating buzzer). Yes, Ms. Bzzz? It's the interview. Thanks, Ms. Bzzz. Will you tell him to wait? Will you wire the car? Will you order the coast? Will you send up the bank? And the telephones blink. And the stocks get sold. And the rest of us, he keeps on hold. And he's into making movies. And he's now a corporation, right? So I play at home with my wife and kids. And I wait to hear the movie bids. And I've got a little sailboat. And I'm into meditation, right? He flies off to California. I discuss him with my shrink. That's the story of the way we work, me and Franklin Shepard, Inc.

(Laughter) I'm surprised at how much I like this.

GROSS: OK. That's my guest, Lin-Manuel Miranda (laughter) the production of the New York City Center Encores Great American Musical series in a production of Stephen Sondheim's "Merrily We Roll Along."

You're so much fun on that. And I really think doing hip-hop rhymes is great preparation for that lyric.

MIRANDA: Absolute, it is.

GROSS: For singing that, yeah. And Sondheim - he's just, like, the most brilliant lyricist. But what are some of the things you feel you learned either from talking with Sondheim - because I know he also gave you feedback on "Hamilton" before you actually put it onstage. So what are things you've learned from actually talking to him or just from, like, getting intimately acquainted with his work?

MIRANDA: A couple of things. First of all, I am one of so many composers he's taken the time to encourage. And I feel very grateful to be one of many. I'm by no means unique in that I've gotten words of encouragement from Steve Sondheim, many in my generation have. And that's been incredible. The way in which he specifically helped me with "Hamilton," first of all, by saying that's a great idea when I first told it to him. I - the first time I met him to work on those translations, he said, what else are you working on? What comes after "In The Heights"? And I said, I think a musical about Alexander Hamilton. And he threw up his head and said, that is a fantastic idea.

GROSS: (Laughter).

MIRANDA: And that moment kept me nourished for months, you know, when the writing was tough, when I couldn't figure out how to end those first four lines of "My Shot." The notion that Sondheim threw up his head and said, that's a fantastic idea, you know, kept me sane. But the thing he always sort of stressed was variety, variety, variety, variety, variety. When you're dealing with a constant rhythm, no matter how great your lyrics are, if you don't switch it up, people's heads are going to start bobbing. And they're going to stop listening to what you're saying. So consistently keep the ear fresh. And keep the audience surprised. And, you know, that was his sort of watchword throughout the writing of "Hamilton." I'd send him a batch of songs. And he'd say, I'm going to say it again - variety, variety, variety. And so I - you know, that was my mantra during the writing of that show.

GROSS: The Sondheim song that's closest to comic rap is, in my opinion, "Not Getting Married," which is done...

MIRANDA: (Rapping) Thank you all. Is everybody here? Because if everybody's here, I'd like to thank you all for coming to the wedding.

GROSS: Yeah. Do more. Do more.

MIRANDA: (Rapping) I'd appreciate your going even more. I mean, you must have lots of better things to do, and not a word of it to Paul. Remember Paul, you know, the man I'm going to marry? But I'm not, because I'd never ruin anyone as wonderful as he is. Thank you all for the gifts and the flowers. Thanks to you all for the cards and the showers. Don't tell Paul, but I'm not getting married today.

GROSS: Anyone who could do that song has an incredible tongue (laughter).

MIRANDA: Absolutely.

GROSS: It's so tricky. It's so fast. And the words are so - just kind of, like, dense and funny and rhymey (ph). And so obviously, you know that song by heart, more or less. And have you thought about that song a lot in terms of intricate rhyme schemes and what the human voice is capable of without totally tripping up?

MIRANDA: Well, I think about that - (laughter) honestly, I think about that song more when people ask me, how did you think rap was going to work on Broadway? And I go, nothing in my show is faster than "Getting Married Today" in "Company."

GROSS: Yeah.

(LAUGHTER)

MIRANDA: So I don't know what you're talking about. There's so much precedent for the work in both, quote, unquote, "hip-hop" and not in terms of patter for the stage. But, you know, what's amazing about "Getting Married Today" is it's also in a master class in making a lyric easy. There are consonants on which you waste air. H - there's no H's in that because if you say ha, you've lost half the air in your lungs. So it's very T's and P's. (Rapping) Thank you all. Is everybody here? - because if everybody's here, I'd like to thank you all for coming to the wedding.

It's more about breath control than being - it's not a tongue twister. It's very consciously not a tongue twister. It's about being able to say it in one continuous breath and getting out of the way and choosing words that do not require any extra air or any extra tongue or jaw work. So it's actually not about trying to make it hard. It's about making it easy.

GROSS: So did you learn that intuitively? Or did Sondheim tell you that that was his intention, to stay away from as many H's as possible and to keep it to things that could easily be said?

MIRANDA: I think I read about that in a conversation he had at some point. But I also knew that intuitively because of the hip-hop artists I liked who rapped fast. You know, they're not trying to make something that's hard for them to perform every night. They're trying to make something that sounds impressive and is a joy to deliver every night. I'm trying to think of, like, a really specific early-'90s example. Queen Latifah - (rapping) Snatch your stature. You're broken - looks more like a fracture. Catch that rapper. Latifah will be back to crash you.

That's Queen Latifah in 1992. And it's fast. There's Queen Latifah's "U.N.I.T.Y." She goes, (rapping) there's plenty of people out there with triggers, ready to pull it. Why you trying to jump in front of the bullet, young lady?

No H's. So you learn intuitively that, like, the writer is trying to make something that flows easily off the tongue.

BIANCULLI: Lin-Manuel Miranda speaking to Terry Gross in 2017. Coming up, James Lapine, Sondheim's co-writer on "Into The Woods," "Sunday In The Park With George" and "Passion" - and Paul Gemignani, the longtime musical director of Sondheim's shows.

I'm David Bianculli. And this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "GETTING MARRIED TODAY")

BETH HOWLAND: (As Amy, singing) Listen, everybody. Look; I don't know what you're waiting for. A wedding - what's a wedding? It's a prehistoric ritual where everybody promises fidelity forever, which is maybe the most horrifying word I ever heard of, which is followed by a honeymoon, where suddenly he'll realize he's saddled with a nut and want to kill me, which he should. Thanks a bunch, but I'm not getting married. Go have lunch 'cause I'm not getting married. You've been grand, but I'm not getting married. Don't just stand there, I'm not getting married. And don't tell Paul, but I'm not getting married today. Go. Can't you go? Why is nobody listening? Goodbye. Go and cry at another person's wake. If you're quick for a kick, you could pick...

BIANCULLI: This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli, in for Terry Gross, back with more of our salute to Stephen Sondheim, who died last week at age 91. Now we hear from one of Sondheim's most important collaborators, James Lapine, who wrote the books for the musicals "Sunday In The Park With George," "Into The Woods" and "Passion." He also directed the original Broadway productions. "Sunday In The Park With George" won a Pulitzer Prize for Drama. And Lapine won a Tony for the book of "Into The Woods," the book of a musical is the part that's spoken, not sung. But some of Sondheim's songs were inspired by, or borrowed from, lines written by Lapine for the shows. Earlier this year, when Terry spoke to him, Lapine had published a book called "Putting It Together: How Stephen Sondheim And I Created Sunday In The Park With George."

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

GROSS: It's interesting that the opening song is from the point of view of the Bernadette Peters character, the model who is in the sun, very hot, very uncomfortable in modeling for the genius painter (laughter) Georges Seurat. But in the meantime, she's just kind of, like, suffering and bearing it.

JAMES LAPINE: Well, I think, first of all, he was - he may have been a genius, and she may have known that at the time, but the one thing Seurat never was a success. He never actually even sold a painting in his lifetime. He died very young. And I think looking back at it - and a lot of writing is unconscious - I think it was a smart move for us to learn about the artist Georges from another point of view and particularly, you know, his mistress, with whom he was, you know, so intimately involved. And it immediately set up the dilemma of life and art and what you give up when you dedicate yourself to any aspect of art or work and how it impacts on your private life. And that song, which I totally, you know, tip my hat to Steve on, did a lot of things dramatologically that helped us get out of the gate in telling our story.

GROSS: So why don't we hear "Sunday In The Park," the opening song from "Sunday In The Park With George"?

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "SUNDAY IN THE PARK")

BERNADETTE PETERS: (As Dot) George, why is it you always get to sit in the shade while I have to stand in the sun? Hello, George. There is someone in this dress. A trickle of sweat, the back of the head. He always does this. Now the foot is dead. (Singing) Sunday in the park with George. One more - the collar is damp, beginning to pinch. The bustle's slipping. I won't budge one inch. Who was at the zoo, George? Who was at the zoo? The monkeys and who, George - the monkeys and who?

MANDY PATINKIN: (As George) Don't move.

PETERS: (As Dot, singing) Artists are bizarre, fixed, cold. That's you, George. You're bizarre, fixed, cold. I like that in a man - fixed, cold. God, it's hot out here. Well, there are worse things than staring at the water on a Sunday. There are worse things than staring at the water as you're posing for a picture being painted by your lover in the middle of the summer on an island in the river on a Sunday.

GROSS: That's the opening song from "Sunday In The Park With George," music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, and the book for the show written by my guest, James Lapine, who also directed the show. And now he has a new book called "Putting It Together: How Stephen Sondheim And I Created "Sunday In The Park With George." So in what you had written - correct me if I'm wrong here - You had written the words like for her character, a dribble of sweat. And Sondheim said, no, no, no, I can't use dribble. And he changed it to trickle. So tell me what you think of that. What went through your mind when he said, not dribble, trickle?

LAPINE: You know, I had only done one musical prior to this. In fact, I was fairly new to the theater in general, having really come to it quite late in my 20s. And I was just fascinated working with him at every turn to learn how he did what he did and why he did what he did. I had no judgments about anything. I just thought, oh, well, that's interesting. And then he - then I would learn the, you know, the genius that goes behind setting words to music and rhyming and all the intricacies that go in into creating a song. So I was just delighted to see Steve every week and give him whatever I could give him to help create the music.

And then finally, he, working on this opening song, would read me couplets that he was writing or, you know, lyrics that he was thinking might go into that song. And it was kind of like being cross-examined by a lawyer, you know, which of these do you like best? You know, OK, you like this one best. Why do you like this one best? And would she say this, would she say that? And it was really, looking back at it, a process where he was really trying to get into my head to sort out who these characters were so that he could know them intimately before he could write anything for them.

GROSS: Can you think of a revelation that came to you from something Sondheim said that you may not have realized or thought of without him?

LAPINE: I think what I learned most from him is the marriage of music to spoken word. And the one maybe major thing he said to me was, let me take care of theme. I can put things in a song that no one will blanch at that you put in a scene and it will scream out as being thematic. It will be cliche if you're trying to say something about, you know, beauty or whatever. And it was wonderful to - you know, that's why no one knows who book writers are, because if it's a good musical, you know the music. And that's why you go to see it. And your job as a book writer ostensibly is to tell a story and connect it song to song. But what people don't realize in the way Steve works is - and why he didn't write a song until the first act was finished is because he melds the two. He robs from his book writers. And it's a back-and-forth conversation as to what the character and what the theme of the show is and how it's expressed. And mostly, a lot of that is expressed in music.

GROSS: OK. So that's really interesting. Can you think of one of Sondheim's songs that you and he agreed should be an emotion or a thematic point that was expressed in the show but would sound too corny or sentimental or on the nose if it was actually spoken as opposed to sung?

LAPINE: I would say "Finishing The Hat" is a perfect example of that, of a song that comes at a perfect place in the act, that lets an audience see this kind of cold, distant character and allows us to understand what he's going through and what his process is and who he is and the pain he feels. But I think what Steve's genius is also on what I guess I would call spotting a musical. You know, he had the first act, but he was often the one to know where there needed to be a song and what that song needed to be about.

GROSS: And part of what this song is about is how difficult it is to create a work of art. But when you've created it, there's something there that had never been there before. You created something that didn't exist before. And if you made that in a speech, it might sound like a little much.

LAPINE: Yeah, corny.

GROSS: Yeah.

LAPINE: ...Corny city. Well, also there's another level to that song, which is him examining what he's given up to make something, what the choices are, what you do with your time and your passion and how you have to distance yourself from other temptations to keep your focus entirely on this vision that you have that you have to bring to fruition.

GROSS: OK. Well, let's hear it. So this is from "Sunday In The Park With George."

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "FINISHING THE HAT")

PATINKIN: (As George, singing) Finishing the hat - how you have to finish the hat, how you watch the rest of the world from a window while you finish the hat. Mapping out a sky, what you feel like planning a sky - what you feel when voices that come through the window go until they distance and die, until there's nothing but sky - and how you're always turning back too late from the grass or the stick or the dog or the light, how the kind of woman willing to wait's not the kind that you want to find waiting to return you to the night, dizzy from the height. Coming from the hat, studying the hat, entering the world of the hat...

BIANCULLI: More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

BIANCULLI: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to Terry's interview from earlier this year with James Lapine, who collaborated with Stephen Sondheim on the musicals "Into The Woods," "Sunday In The Park With George" and "Passion." We're revisiting the interview as part of our salute to Sondheim, who died last week at age 91.

GROSS: And now I want to ask you about "Passion." And to give the shortest version, it's about a soldier who's having a passionate affair with a beautiful woman who's sent to a remote outpost where the cousin of the commander is a very sickly - I mean, she's very ill woman who is considered very ugly by the other soldiers there. And she basically lives in books. She reads to live. And by the end, the main character, the soldier, gets sick, too, and they actually develop a loving relationship. She's fallen in love with him much earlier, and he's done everything in his power to reject her earlier in the musical. So what is - can you choose a song from that that you feel really connected to in terms of contributing to it, some lines or it was based on a monologue that you wrote?

LAPINE: Well, there's a song that was the last one that came in, again another kind of beautiful short song that Steve wrote called "Loving You." And we were having a horrible time in previews. The audience was just not buying the fact that this gorgeous guy is going to fall in love with this sickly and unpleasant woman, really. And I realized in previews that we had to tell the audience - literally - what it was that made him fall in love with her. She explains for the first time what love is for her, and she realizes that love is not throwing herself at his feet, but just being there. And she turns his head around about what love is. And the simple little song, when it came into the show, really dramatically helped us bring the audience along on this kind of far-fetched tale.

GROSS: So let's hear "Loving You" from the musical "Passion." And this is Donna Murphy.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "LOVING YOU")

DONNA MURPHY: (As Fosca, singing) Loving you is not a choice. It's who I am. Loving you is not a choice and not much reason to rejoice, but it gives me purpose, gives me voice to say to the world this is why I live. You are why I live. Loving you is why I do the things I do. Loving you is not in my control. But loving you, I have a goal for what's left of my life. I will live, and I would die for you.

GROSS: That was Donna Murphy singing "Loving You" from the musical "Passion" with music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim. The book for the show was written by my guest, James Lapine.

LAPINE: You know, I think that show - and I would say this for Steve, too - it somehow struck us on such a deep level that we couldn't even articulate why. It just moved us. And it created a really interesting challenge for us to hold an audience's attention on that kind of a theme because it's threatening to people. I remember sitting in the audience, and there were a lot of married couples around me. And the show starts, of course, with these two naked, gorgeous people making love. And the guys in the audience in particular are like, yeah, this is the show for me, you know?

(LAUGHTER)

LAPINE: And then the show starts, and about 30 minutes in, they're squirming in their seats. And, you know, 40 minutes in, they're trying to poke their wives and get the hell out of there. But it asks a lot of us to question what love is and question, you know, are we just interested in the surface of people and not actually what their heart and brain is? And I could feel married couples questioning themselves about, are we still in love? Is this passion? Is it love? Whatever - it raises a lot of questions for people, this show.

GROSS: Are you and Sondheim still good friends?

LAPINE: Oh, my God, yeah. I consider him one of my absolute closest friends.

GROSS: I'm glad to hear that.

LAPINE: I'm very lucky. And I mean, when you go through what we went through on those three shows, you know, you are joined at the hip for life.

BIANCULLI: James Lapine speaking to Terry Gross earlier this year. His recent book about working with Sondheim is called "Putting It Together: How Stephen Sondheim And I Created 'Sunday In The Park With George.'" Coming up, we conclude our multi-day Sondheim salute by visiting with his frequent musical director Paul Gemignani. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF THE TROTTER TRIO'S "HAPPINESS (TRIO)")

BIANCULLI: This is FRESH AIR. Paul Gemignani began working with Stephen Sondheim as his music director in 1973 on such musicals as "A Little Night Music," "Sweeney Todd," "Sunday In The Park With George" and "Passion." Terry Gross spoke with Paul Gemignani in 2001, when he was given a Tony Award for lifetime achievement. Gemignani says he particularly enjoyed serving as music director on Sondheim's "Sweeney Todd," which premiered on Broadway in 1979. Here's the opening.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "PRELUDE: THE BALLAD OF SWEENEY TODD")

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #2: (As character, singing) Attend the tale of Sweeney Todd. His skin was pale, and his eye was odd. He shaved the faces of gentlemen who never thereafter were heard of again. He trod a path that few have trod did Sweeney Todd, the demon barber of Fleet Street.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

GROSS: In "Sweeney Todd," I think the first sound we hear is that steam whistle, a really...

PAUL GEMIGNANI: Correct, correct.

GROSS: ...Like, discordant, shrill, alarming steam whistle that certainly sets the tone for, you know, a musical that's about very alarming thoughts...

GEMIGNANI: Right.

GROSS: ...And feelings and actions...

GEMIGNANI: Right.

GROSS: ...Including murder and revenge. Well, did you actually have a steam whistle...

GEMIGNANI: Yes.

GROSS: ...In the orchestra?

GEMIGNANI: What it said - in the opening thing on the top, it said, whistle. Factory whistle is what it said. So we sat down and had discussions about what a factory whistle was. The thing that popped into my mind is those old English factory movies, Dirk Bogarde movies where he's in a blue-collar section of somewhere in Britain. And his father works in the mines or in the factory. And on the top of that factory is this whistle that's actually made - worked from steam - right? - pretty shrill.

And we finally found this actual factory whistle, and we hooked it up to a CO2 canister, and that's how we operated it. I operated it, actually, from a switch in the pit. And I'd play it. I think we almost all passed out from the sound. But it did what it was supposed to do. It was so intense that they had to keep moving it further away. So the audience would, you know, like, leap out of their seats.

GROSS: Can you think of a moment in a musical that you conducted where every night, you'd say to yourself, this is what it's about for me; this is the kind of musical feeling, the kind of Broadway feeling that I live for?

GEMIGNANI: I have to say "Sunday In The Park." I have to say when when Mandy and Bernadette sing "We Do Not Belong Together." That's a moment that popped into my mind when you asked me that question. I'm sure that there's a thousand others. But, you know, working - the 12 years I worked with Steve - and, hell, I don't have to work anymore after that. I mean, all the thrill and all the expectations I had as an artist were fulfilled in that 12 years. Do I - am I tired of working now? No. And will I not - will I continue until I can't work anymore? Absolutely.

I'm just saying that (laughter) I feel kind of greedy at this point because I've had such great experience and great times in the past and had an opportunity to do so much artistically because of those two guys. You know, everything else is gravy, but that one place in "Sunday In The Park" sticks in my mind.

GROSS: Let's listen to that duet between Mandy Patinkin and Bernadette Peters from "Sunday In The Park With George."

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "WE DO NOT BELONG TOGETHER")

PETERS: (As Dot) Yes, George. Run to your work. Hide behind your painting. I've come to tell you I'm leaving because I thought you might care to know - foolish of me because you care about nothing.

PATINKIN: (As George) I care about many things.

PETERS: (As Dot) Things, not people.

PATINKIN: (As George) People, too. I cannot divide my feelings up as neatly as you. And I am not hiding behind my canvas. I am living in it.

PETERS: (As Dot) What you care for is yourself.

PATINKIN: (As George) I care for this painting. You will be in this painting.

PETERS: (As Dot, singing) I am something you can use.

PATINKIN: (As George, singing) I had thought you understood.

PETERS: (As Dot, singing) It's because I understand that I left, that I am leaving.

PATINKIN: (As George, singing) Then there's nothing I can say, is there?

PETERS: (As Dot, singing) Yes, George, there is. You could tell me not to go. Say it to me. Tell me not to go. Tell me that you're hurt. Tell me you're relieved. Tell me that you're bored. Anything, but don't assume I know. Tell me what you feel.

PATINKIN: (As George, singing) What I feel? You know exactly how I feel. Why do you insist you must hear the words when you know I cannot give you words, not the ones you need? There's nothing to say. I cannot be what you want.

PETERS: (As Dot, singing) What do you want, George?

PATINKIN: (As George, singing) I needed you, and you left.

PETERS: (As Dot, singing) There was no room for me.

PATINKIN: (As George, singing) You will not accept who I am. I am what I do, which you knew, which you always knew, which I thought you were a part of.

PETERS: (As Dot, singing) No. You are complete, George. You are your own. We do not belong together. You are complete, George. You all alone. I am unfinished. I am diminished with or without you. We do not belong together. And we should have belonged together. What made it so right together is what made it all wrong. No one is you, George. There we agree.

GROSS: That's "We Do Not Belong Together" from "Sunday In The Park With George." Conducting that was one of music director Paul Gemignani's favorite Broadway experiences. I asked him to think of another.

GEMIGNANI: The first thing that Sweeney sings in "Sweeney Todd" to his razors, that moment sticks in my mind.

GROSS: "Friends"?

GEMIGNANI: "Friends," yeah.

GROSS: This is the moment when the barber Sweeney Todd, who's been put in prison, is out of prison. He's seeking revenge against the judge who locked him up and shouldn't have. And the judge is now planning to marry Sweeney's daughter. It's an ugly story. But finally, Sweeney's reunited with his razors, and he's going to use them not only to be a barber, but to take his revenge. And he sings this beautiful song about how he's reunited with his friends. But what he's really thinking about is revenge.

GEMIGNANI: Right.

GROSS: What's so wonderful about this moment for you, conducting it?

GEMIGNANI: Well, the beauty of the music and the irony of the idea, it gives you something to perform. It's not, you know, it's not 32 bars in four-four time. It's a beautiful melody, you know, intense, dramatic moment that's taking the story from one place to another. That is the theater to me, musical or otherwise.

BIANCULLI: Paul Gemignani speaking with Terry Gross in 2001.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "MY FRIENDS")

LEN CARIOU: (As Sweeney Todd, singing) These are my friends. See how they glisten. See this one shine. How he smiles in the light. My friend, my faithful friend, speak to me, friend. Whisper. I'll listen. I know. I know. You've been locked out of sight all these years like me, my friend. Well, I've come home to find you waiting - home. And we're together. And we'll do wonders. Won't we? You there, my friend.

ANGELA LANSBURY: (As Mrs. Lovett, singing) I'm your friend, too, Mr. Todd.

CARIOU: (As Sweeney Todd, singing) Come. Let me hold you.

LANSBURY: (As Mrs. Lovett, singing) If you only knew, Mr. Todd.

CARIOU: (As Sweeney Todd, singing) Now, with a sigh.

LANSBURY: (As Mrs. Lovett, singing) Oh, Mr. Todd.

CARIOU: (As Sweeney Todd, singing) You grow warm in my hand.

LANSBURY: (As Mrs. Lovett, singing) You're warm in my hand.

CARIOU: (As Sweeney Todd, singing) My friend.

LANSBURY: (As Mrs. Lovett, singing) You've come home.

CARIOU: (As Sweeney Todd) My clever friend.

LANSBURY: (As Mrs. Lovett) Always had a fondness for you, I did.

CARIOU: (As Sweeney Todd) Rest now, my friend.

BIANCULLI: And that concludes our salute to Broadway composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim, who died last week at age 91. He left the musical theater a much richer place and has one last gift to give us. A new film version of "West Side Story," for which he wrote the lyrics, opens in theaters next week.

On Monday's show, Kieran Culkin, one of the stars of the HBO series "Succession." It's a comedy embedded in a drama about corporate, political and personal wealth and power. Culkin plays one of three adult siblings vying to take over the family run conglomerate, which includes a conservative cable news network, when their elderly father retires or dies. I hope you can join us. FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our senior producer is Roberta Shorrock. For Terry Gross, I'm David Bianculli. Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.