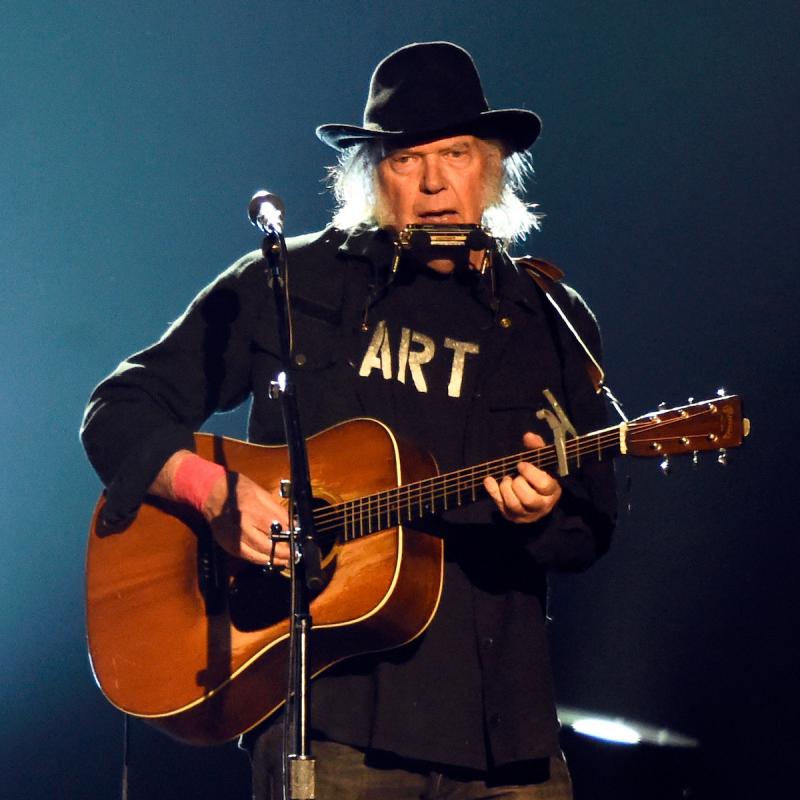

Decades Later, Neil Young Continues to Rock

In 1966, Neil Young joined L.A. rock band Buffalo Springfield; they split up three albums later due to inter-band fighting and their lack of commercial success. Young's new album is Praire Wind, considered a follow-up to his Harvest records.

Other segments from the episode on September 30, 2005

Transcript

DATE September 30, 2005 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Neil Young discusses his music and career

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli, TV critic for the New York Daily

News, sitting in for Terry Gross.

When singer-songwriter Neil Young was a young man, singing to and about his

dad in the song "Old Man," his lyrics included a line referring to his own age

and outlook--`24 and there's so much more.' Well, Neil Young is about to turn

60, and his new album features songs devoted mainly to looking backwards. His

father died in June at age 87. Young himself suffered a brain aneurysm in

March. But in the days between his diagnosis and surgery, he went into the

recording studio and recorded a series of brand-new songs. After recovering,

he returned to the studio and completed the process, and the new CD, called

"Prairie Wind," which was released last week.

The songs appear in the order in which Young recorded them, in the style of

his more intimate acoustic albums like "Harvest," "Comes a Time" and

"Harvest Moon." They touch on such resonant subjects as family, memory, home,

faith, the beauty of wilderness and the joy of music. "This Old Guitar" is

about the instrument he's playing, once owned by Hank Williams. "Prairie

Wind," the title song, is about Neil's father and begins by confronting

frankly the dementia that dominated his dad's last years.

(Soundbite of "Prairie Wind")

Mr. NEIL YOUNG: (Singing) Tryin' to remember what my daddy said, before too

much time took away his head. He said, `We're going back and I'll show you

what I'm talking about. Going back to Cypress River, back to the old

farmhouse.'

Backup Singers: (Singing) Prairie wind blowin' through my head, prairie wind

blowin' through my head. Tryin' to remember what Daddy said. Prairie wind

blowin' through my head.

Mr. YOUNG: I'm tryin' to tell the people but they never heard a word I say.

See, there's nothing out there but wheat fields, anyway. Just a farmer's wife

hanging laundry in her back yard, out on the prairie where the winds blow long

and hard.

BIANCULLI: That's the title song from Neil Young's new CD, "Prairie Wind."

Young performed the entire album in concert last month at Nashville's Ryman

Auditorium, the former tabernacle that served for more 30 years as the home of

the Grand Ole Opry. The concert was filmed by Jonathan Demme, who plans to

make a movie based around Young and this brand-new album.

We're going to hear from two of Terry's interviews with Neil Young. She spoke

with him first in 1992, when "Harvest Moon" was released.

TERRY GROSS, host:

You were in high school bands. Did you sing in those bands?

Mr. YOUNG: After the beginning, I did. I started as an instrumentalist. We

used to do songs, instrumentals that I used to write, you know, melodies and

playing on the guitar, sort of like a group called The Shadows from England,

and then after the English invasion, you know, in the--and also about the same

time as Jimmy Reed became popular, the old bluesman, Jimmy Reed, with

going to New York in...

GROSS: Bright lights, big city?

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah ...(unintelligible) and all these things, you know.

He--about the same time as the British invasion, all these groups singing

harmony and playing guitars and everything, both of those things happened to

me at once, so I really couldn't figure out who it was that made me want to

sing, but one of them, you know, or both of them at the same time. And I

started singing, and that was like a milestone.

GROSS: What do you mean?

Mr. YOUNG: People couldn't believe it, apparently. I don't remember it, but

I was so into it I guess I didn't notice that everybody was going, `What

the--what is that?' you know, as I was starting to sing. Of course, now I'm

like, you know, Caruso or something. Got it down.

GROSS: Were you self-conscious about your voice when you started to sing?

Mr. YOUNG: No, not really. I never really--I was just glad to be singing.

Meant we could a lot more songs if I sang them.

GROSS: No one else in the band could sing.

Mr. YOUNG: No. Not...

GROSS: Is it...

Mr. YOUNG: Nobody in the band could sing, not `nobody else in the band.'

Nobody in the band, so we did harmony and we did everything, you know. But it

didn't matter.

GROSS: Now you say that you were unself-conscious about your singing, but

there are stories about how, you know, like in your first solo album you

intentionally mixed yourself in the background.

Mr. YOUNG: No, I mixed myself right up there where I should be, and then

they tried out this new scientific process that they'd invented called the

CSG-Haeco clog process, which is this unbelievable thing where you can make

a stereo record play back on a mono machine just like it was a mono record.

They did some thing to the sound back then. This was when stereo was just

coming out, and there were--you know, a lot of people had mono sets and the

stereo didn't sound right on a mono set, so they came out with this thing.

You run it through this machine that this guy made, this little box or

something, and it would make it so you could play it both stereo or mono.

But in reality, I was a test case for this with my first album. They did this

without letting me know, and they put it out like that, and I got the

pressings back, and I went, `What happened?' you know? Then I read this thing

had been added on the album cover where--with this engineering note that this

had employed this technique, and really, it was the worst thing I ever heard.

I mean, they just buried the whole center of the record and put it way down,

and this--so I think they only used it on my record. They decided it didn't

work after that.

GROSS: So it wasn't self-consciousness that was behind it.

Mr. YOUNG: No. I could go to the next record. I think my vocal is right up

there.

GROSS: How did you feel about being in a tight harmony group like Crosby,

Stills, Nash & Young? Did...

Mr. YOUNG: How did they feel about it, that's the question. It was no

longer a tight harmony group.

GROSS: Do you like being in a harmony like that? I mean, I love your voice.

I consider it a very personal voice. Do you know what I mean, a voice that

should be singing on its own more so than just like mixed in a harmony?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, you know, I like singing harmony, too. I sang good harmony

with Crazy Horse, and there's a sense in there that--you know, because there's

a couple of different ways to sing harmony, you know. You can--or blends of

all of them, but one of them is just real tight harmony and the other one is

where everybody's singing just--more or less just singing loose but in a

harmonic structure, with a lot of feeling. That's a different kind of

harmony, and that's the kind of harmony that I do with Crazy Horse quite a

bit. Sometimes we're real successful at that.

GROSS: So you came from Canada to Los Angeles, became part of Buffalo

Springfield, and I guess it was in '66, you have a really big hit, "For What

It's Worth," and then, you know, people just, like, loved Buffalo Springfield.

So this is, like, the height or the beginnings of the height of the whole kind

of counterculture, which was really thriving, particularly on the West Coast.

And so suddenly, like, you're really in the thick of it, I mean, gone

from--What?--a small town in Canada, right?

Mr. YOUNG: Yes, kind of a--half a million people, something like that.

GROSS: Uh-huh, and now, like, you're really in the thick of it, did you

change a lot? Were you, like, a kind of different person than you were?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, you know, I think it affected me. I think it got to be a

lot of pressure for a while, but you know, we got through that after freaking

out and quitting the band a couple of times and, you know, throwing my guitar

against a chair and doing all kinds of stuff. You know, we went through a

normal kind of teen-age-to-adult changeover period there.

GROSS: When you throw your guitar against a chair, do you--in the days when

you did that, was it--were you sure you had money to replace it...

Mr. YOUNG: No. That was the point.

GROSS: ...before you threw it?

Mr. YOUNG: No. No, I think--I didn't do that every day, but it's just

part--I guess the pressure of being in the band and trying to make things

happen, you know--we did a lot of things like that. I mean--What?--we were

20, 21 years old. We were kind of crazy for a while, and then, you know, just

like anybody else under a lot of pressure. Bunch of kids, and you know, it

was a pretty fast-moving time.

GROSS: What's something that you look back on and still find really exciting

about that period?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, the music was great, and it's too bad it was never recorded

correctly or it would--you know, the Buffalo Springfield would have been far

more of a memory than they are now.

GROSS: What's missing?

Mr. YOUNG: The music is missing. There was--you know, this was about the

time when people started making records by overdubbing and new technology was

coming in. We had like eight-tracks and you know, big--we had ways of doing

things that weren't--that made it possible to layer records. And so instead

of going in the studio and singing live--like we were so great live--the

people producing us, they didn't record us the way they should have. If

they'd have just set us up and let us record live, this band would be--band

probably would have been together and stayed together a lot longer because we

would have had much more success and had a lot more happiness from listening

to our records and, you know, felt like we were getting something done.

But at the beginning it was kind of hard to break through. You know, we still

didn't know how to make records and we didn't have anybody that knew how to

make records helping us make records. And instead we had people who wanted to

be record producers for, you know, one reason or another who were there, but

they really weren't doing anything. Nobody strong came along and said,

`Listen, you guys go in there and sing, and then when I tell you to come out,

you stop playing and singing, then come on in here and it'll sound great.'

Nobody ever did that. So I feel that was the failing of the Buffalo

Springfield, was all the records. There was--only Ahmet Ertegun really had a

grip on what should be--what the Springfield records should sound like.

GROSS: What sounds best to you now from those records?

Mr. YOUNG: I don't have a favorite.

GROSS: OK. I thought I'd play "Mr. Soul" Do you--what are your memories

of that?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, memories of that are the best take of it and the best mix

of it and the best version of it is somewhere in the Atlantic vault.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. YOUNG: And the one that we're listening to here is one that--where we

got away from it and we kept overdubbing and overdubbed guitar parts and added

things over top of the original stuff, and lost some of the original stuff and

we took it too far. We didn't have anybody to tell us to go home or tell

us--that had experience--telling us what to do. So we lost a lot of the great

stuff that we had on tape in the first place or that we never--we never got a

lot of it on tape at all.

GROSS: OK. Well, in the meantime, we'll satisfy ourselves with the...

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah.

GROSS: ...artfully released version of "Mr. Soul."

(Soundbite of "Mr. Soul")

BUFFALO SPRINGFIELD: (Singing) Oh, hello, Mr. Soul, I dropped by to pick up

a reason for the thought that I caught that my head is the event of the

season. Why, in crowds just a trace of my face could seem so pleasin'. I'll

cop out to the change but a stranger is putting the tease on. I was down on a

frown when the messenger brought me a letter. I was raised by the praise of a

fan who said I upset her. Any girl in the world would have easily known me

better. She said, `You're strange, but don't change,' and I let her.

BIANCULLI: That's Neil Young's song, "Mr. Soul," recorded in 1967 with

Buffalo Springfield. His newest album, "Prairie Wind," has just been

released. Terry spoke with him in 1992.

When we come back, we'll hear a more recent conversation with Neil Young.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of unidentified song)

Unidentified Group: (Singing) Round and round and round we spin, too evil

world to end our sin. It won't be long...

BIANCULLI: When Neil Young's movie-and-CD project "Greendale" was released

last year, Terry, fighting a bad cold, spoke with him again. It was a project

that didn't really fit in with the 21st-century music scene, but Neil told

Terry that not fitting in is something he'd been comfortable with his whole

life.

Mr. YOUNG: Even when I was in school, I felt--I was always happy to wear

clothes that had gone out of style. To me--whenever they were really out,

that's when they were really in for me.

GROSS: Oh, what'd you wear?

Mr. YOUNG: Like I was wearing white bucks, like, 10 years after Pat Boone,

you know?

GROSS: Where'd you get them?

Mr. YOUNG: And I had the little thing that you--you know, where you paint

them white with this little spongy thing and everything like...

GROSS: Oh, I remember that, yeah.

Mr. YOUNG: I'd do that, you know, and I'd take off to school, you know,

wearing my white bucks and red socks. You know, maybe I was the devil or

something. I don't know. But, you know, to me it was like--I was a rock 'n'

roll guy. I didn't care about, you know, what was happening. I really didn't

like the preppy kids at school that much and, you know, I didn't want to blend

in with them. And, you know, I look around. I see people today. There--I'm

there. I'm still in the classroom. They're still there, you know, my

brothers in arms, whoever they are.

GROSS: Although you have been unpredictable and always moving forward in your

music, there have been a couple of real constants in your life over many

years. One was Crazy Horse, a fairly constant part of your musical life, and

the other is your family. I mean, you even tour with your wife and usually

with your two sons.

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah, my daughter, too.

GROSS: Did you ever expect that so much of your life would revolve around

family and around being a father?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, I never really thought about it.

GROSS: As a rock 'n' roll guy, you know? As...

Mr. YOUNG: Well, I've broken a lot of the rock 'n' roll rules by being

married for 25 years, and, you know, I guess it's all because I have such a

wonderful wife. I mean, I--you know, we don't have a textbook kind of, you

know, Cleaver family type of marriage, but we have a--you know, we got a rock

'n' roll marriage and it's great, and she's adapted. And the telling thing

about our marriage, I think, and the proof of its goodness is the fact that

I've been able to remain creative and that I've been able to change

throughout. Some people, when they get married, they so-called `settle down'

and they fit into something. Some people, when they get into relationships,

adapt their personalities to fit the relationship and then they lose

themselves. And you know, living with Peggy has never put the strain on

me to do any of those things, and it's always been a good thing and she's

always, you know, been behind the things that I've done. Even if she admitted

that she didn't understand what I was doing or didn't know if it was the right

thing or whatever, she was still behind the creative part of what I was

endeavoring to do.

GROSS: Now your two sons both have cerebral palsy. Your older son has a

milder case, your younger son a severe case that's left him basically a

quadriplegic. And he can't talk, either. Does he understand speech?

Mr. YOUNG: Oh, yeah. Oh, sure, yeah. He understands what's going on,

because, you know, even when you start spelling things that he wants to do, he

gets very excited about things. So if I was to mention something that he

really wants to do, he anticipates a lot, you know, so if like--if we were to

talk about it--so you just drop one word and he's going--I mean, jumping out

of his chair. So yes, he does understand what's being said around him, and he

also understands--you know, he's learning how to spell because we stopped

saying certain things that would get him so jacked up and started spelling

them, and he figured that out. So you know, he's all there in that way, and

he's a real good communicator. He just--you just have to get used to how he's

communicating and learn how to communicate with him, and he's got a lot of

soul, that guy.

GROSS: In listening to you tell part of the story of "Greendale," it seemed

to me that you really enjoy storytelling. Were you able to tell stories to

Ben when he was growing up?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, you know, I just talk to Ben about everything, so Ben

probably knows more about me than anybody. And, you know, because I--Ben, I

figure that the best thing I could do is just tell him, you know,

mostly--almost everything that was on my mind, unless I thought it was

something that might scare him or something, you know. So I just--Ben and I

spend a lot of time together and I'm always talking.

GROSS: I wonder if you think your music has been affected--like, does Ben

respond a lot to music?

Mr. YOUNG: Oh, yeah. Yeah, he's subtle in his response to it. But my music

has definitely been affected by being the father of Ben and Zeke and all

the kids. They're all--you know, it's about how hard things are for people

with disabilities. When you live with someone with a disability and you

realize what they have to go through to do certain things that we take for

granted, and then you see somebody in perfectly good health or somebody

saying, `Oh, that's too hard. I can't do that,' there's something that snaps

in me when that happens. There's nothing that I can't try to do if I want to

do it. I know how hard it is for my son to do what he wants to do.

GROSS: Do you think that helped you grow up, and I mean this in the sense

that there's a lot of rock stars who in some ways seem to have never grown up?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, I don't know how much I've grown up. Part of me might have

grown up a long way, and another part of me may just be way back there in

kindergarten or something. But, you know, life--you know, my life has been

very extreme, so I've learned to accept extreme things and to, you know, take

strength from them.

BIANCULLI: Neil Young, speaking with Terry Gross. We'll hear more in the

second half of the show. I'm David Bianculli and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of unidentified song)

CROSBY, STILLS, NASH & YOUNG: (Singing) Sailing hardships through broken

harbors out on the waves in the night. Still a searcher must ride the dark

horse racing along in his stride. Tell me why, tell me why. Is it hard to

make arrangements with yourself when you're old enough to repay but young

enough to sell? Tell me lies, later come and see me. I'll be around for a

while...

(Announcements)

BIANCULLI: Coming up, getting his first guitar. We continue our conversation

with Neil Young. His new album is "Prairie Wind." Also, David Edelstein

reviews "Capote," the new film about Truman Capote and the writing of his

great true book, "In Cold Blood."

(Soundbite of music)

BIANCULLI: This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli sitting in for Terry

Gross.

Let's get back to our conversation with Neil Young. His new album, "Prairie

Wind," has just been released. It was recorded last spring right after

Young learned that he had a brain aneurysm that would require surgery. In the

few days between the diagnosis and the operation, Young flew to Nashville and

recorded eight of the 10 songs on the album. "Prairie Wind" also includes a

DVD which documents the recording session. Here's another song from that

album.

(Soundbite of "Here For You")

Mr. YOUNG: (Singing) When your summer days come tumbling down and you find

yourself alone, then you can come back and be with me. Just close your eyes

and I'll be there. Listen to the sound of this old heart beating for you.

Yes, I miss you, but I never want to hold you down. You might say I'm here

for you.

BIANCULLI: "Here For You" from Neil Young's new CD "Prairie Wind." Let's get

back to his interview with Terry. It was recorded last year when Terry was

fighting a cold.

GROSS: Now I read someplace--and I don't know whether this is true or

not--that you had polio when you were a child.

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah.

GROSS: You did?

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah, I did. I was six.

GROSS: How did it affect you? I mean, what--physically...

Mr. YOUNG: Well, you know, I had to learn how to walk again at six. And

that's basically all it was, you know? Part of my body's not quite as

sensitive as the rest of it, my left side, but it's no big deal. I just

learned how to deal with it.

GROSS: Were you listening to music yet when you were that young? 'Cause I

know sometimes when kids are sick, they just like--they read a lot, listen to

music, and it really changes them.

Mr. YOUNG: I can't remember when I wasn't listening to music, OK?

GROSS: What were you listening to when you were young?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, the first thing I remember was--you know that song "The

Three Bells," that French song about--you know, "The Three Bells" it's

called. The Browns did a version of it about 40 years ago.

GROSS: Oh, yeah.

Mr. YOUNG: Well, the original version was a French version and, God, it was

so beautiful and we had it on a 78. I used to listen to it over and over

and over again, that and we had a version of "Greensleeves" that I used to

listen to all the time and just...

GROSS: Can you sing a couple of the bars of "The Bells" so listeners will

know the song you're talking about?

Mr. YOUNG: You know the one. (Singing) `In a little congregation,' you know,

`prayed for guidance from above and'--remember that song?

GROSS: I do. I do. It was, like, a hit...

Mr. YOUNG: Little Jimmy Brown, a story of Jimmy Brown or whatever it was.

GROSS: Yeah. It was, like, a hit in the early '60s or something.

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah. Yeah. And that was the English version. The French

version, the first one, was just sensationally great and really beautiful.

The English one was good, too, but the one I heard was the French one. So I

don't know. I can't even remember how I understood what it was, but it didn't

seem to matter.

GROSS: Did you parents buy you a lot of kids' records?

Mr. YOUNG: Did my parents buy me a lot of kids' records?

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. YOUNG: No, I bought my own records. I went out--you know, I used to

have a little--a couple of businesses when I was a kid, chicken business. I

raised chickens and sold eggs and everything, and I also would, you know, go

find golf balls at the golf course and sell those to the golfers. Quite often

the same ball a guy had, I sold to him.

GROSS: What a racket.

Mr. YOUNG: That's where I got my sales expertise. And so after that, you

know, I had a little bit of money and I'd go down and buy the latest 45 RPMs

or whatever and, you know, I think I bought a lot of records when I was a kid.

And I used to listen to WLS out of Chicago. Even though I was way up in

Winnipeg, I could still pick it up. And I used to listen to, you know, Dick

Biondi and, you know, a little Alan Freed and I could get that, the old rock

'n' roll.

GROSS: So this is great. So you raised chickens and sold eggs and resold

golf balls so that you could buy 45s.

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah, more or less that's it. Yeah.

GROSS: What were the very first records you remember buying?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, the first records that I--one of the earliest ones I think

was old Jerry Lee Lewis records and Little Richard and those records, and then

about the late '50s and early '50s I bought, you know, records by The

Monotones and Buddy Holly and--What's that?--Ronnie Self and The

Chantels, all these great records, you know, R&B type records. And then Jimmy

Reed--I bought all of Jimmy Reed's albums when I was in grade eight or nine

or something in high school and I had all his early records. And, you know, I

just bought--I really liked R&B.

GROSS: And when did you get your first guitar?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, my dad bought me a ukelele. I guess I was around eight.

GROSS: Why did he get you a ukelele as opposed to a guitar?

Mr. YOUNG: It's small.

GROSS: Oh, sure.

Mr. YOUNG: Small enough for me.

GROSS: Sure.

Mr. YOUNG: It was just a little plastic Arthur Godfrey one. Then he

played it for me and he sang all these sad songs, you know, "Bury Me Out On

The Prairie," and all of these ridiculous cowboy songs that he knew from

God knows where. And then he'd smile and he'd play it along, and then after

that, my uncle came by and, of course, he was really good on the ukelele and

he played the thing and played all these chords and then it turned out he

could play anything. He played piano, guitar, ukelele, horns, and then he

even played his three daughters. He had them singing. He had them in

three-part harmony, singing background for him while he was singing, and he

taught them all these things. It was amazing, and so my cousins all sang, you

know, harmony.

GROSS: So when did you switch from ukelele to guitar?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, right after the ukelele, I got a thing called a banjo

ukelele, which plays like a ukelele but looked like a banjo. I think it cost

about 15 bucks. I got it for Christmas one year. Then I got a baritone

ukelele. It's like a ukelele, but it's bigger, kind of like a really small

guitar, and then I advanced up to the guitar 'cause the first four strings on

a guitar are the same notes as a ukelele, basically, so I advanced.

GROSS: Did you get lessons on any of this?

Mr. YOUNG: I had two guitar lessons in 1962.

GROSS: Well, I take--it took you a long way, I guess.

Mr. YOUNG: Well, it took me a long time to get to the place where I had to

take them, and I hated those lessons. I never could understand what they were

trying to show me, so...

GROSS: What did you hate about them?

Mr. YOUNG: ...I don't think I learned anything.

GROSS: What did you hate about the rest of them?

Mr. YOUNG: I don't know. I didn't remember. I tried to block it all out of

my head. I don't even remember what they were trying to show me. It's one of

those things I didn't enjoy that luckily my mind works such that now I don't

remember any of it. I don't even remember walking in the door. It's all

gone.

GROSS: Are there any things that you taught yourself that are officially

wrong?

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah. Yeah. Sure, all kinds of things, like--officially wrong

for guitar playing, you mean?

GROSS: Mm-hmm. Yeah.

Mr. YOUNG: Ah. Well, playing out of tune is pretty wrong. I do that

regularly. And I will continue playing out of tune if I think it has some

kind of a sound. And, you know, usually I'm--you know, my sound mixer, Tim

Mulligan, has been working with me for about 30 years. He comes up to me

and says, `Now, listen, your guitar sounds a lot bigger'--he just told me this

yesterday. He said, `Your sound is a lot bigger when you're in tune. So why

don't you just take a minute and tune up in between songs, you know, if

you'--so the other night, I actually stopped and I gave my guitar to Larry, my

guitar tech, and he tuned it right in the middle of--you know, I'm not that

good at tuning. I got these Strobotuners and I use them, but it's

distracting. Tuning is distracting.

There's something about--and then when I have to take my guitar off and have

somebody else tune it, I feel like I'm naked up there. I don't know what the

hell to do with myself standing there in front of all these people screaming

and yelling 'cause we just tore the house down doing something and then I

don't have my guitar. I'm waiting for it to be tuned, you know? It's a very

kind of vulnerable moment when I don't have the guitar. So rather than tune

or do anything, I just want to keep playing because I know how to play, you

know? So that's--I get in trouble there. That's majorly wrong to play out of

tune and I do that a lot.

GROSS: That's great that you play out of tune because you can't give up your

armor.

Mr. YOUNG: That's right. I try to keep it in tune, you know? I have a lot

of ways of hiding being out of tune.

GROSS: Your guitar playing just keeps evolving and, I mean, there are so many

different voices and styles that you can use to such kind of dramatic or

emotional effect. I'm wondering: Do you think that that comes in part from

always listening to new things or is what you're playing not related to what's

coming in as input?

Mr. YOUNG: You know, guitar playing is--you know, I guess a metaphor for

guitar playing would deep-earth mining or something. You just keep banging

away, blowing through and trying to get to the core and just keep on going and

melting through layers and just keep pushing. And I, you know, try to keep an

air hose going so you can get back and so you can get a breath, but you've got

to get as deep as you can and go down and keep digging. And that's what

guitar playing is like for me. Every solo I'm looking for a way to go deeper.

I'm looking for which--how am I going to lose myself? How can I get to a

point where nothing matters? How can I stop thinking? How can I lose track

of what's going on and still be in sync? Those are the goals of guitar

playing.

GROSS: Now do you want to stop thinking in a kind of meditative sense, that

it feels good and it's a kind of good state to be in to stop thinking, or do

you want to stop thinking because thinking interferes with playing?

Mr. YOUNG: Thinking is in the way. You know, it's just in the way. It's all

about feeling and there is some kind of an ability to play that happens

because your mind is doing something. It's saying, `OK. Now you can do this.

Now you can do that.' But that's more like tools that I have when I'm boring

into something.

BIANCULLI: Neil Young speaking to Terry Gross last year. More after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

BIANCULLI: Let's get back to Terry's 2004 interview with Neil Young. His

newest album "Prairie Wind" has just been released.

GROSS: When you were younger, were you obsessive about technique and did you

get enough kind of technique through obsession that enabled you to, like, stop

thinking it and go for emotion?

Mr. YOUNG: The first time, you know, I remember--maybe I was 17 or something

and I was playing, and, you know, I worked on things. I learned songs. I

wrote a lot of instrumentals myself and I practiced them and get to play them

and everything, but they didn't have a lot of improvisation in them. And, you

know, they had melodies and I liked the melodies, and then I started singing

and I liked the way it felt when I sang a certain melody and got a certain

sound. But really, God, guitar playing and thinking is so deep, I just--the

guitar playing itself is--you know, when I was young--I think I was about

17--I was playing in this little club and I had my band and we were doing a

cover song. We played a song by The Premiers called "Farmer John," and there

were some other musicians around. And one of them was a really, really good

guitar player and he really could just bend the strings on his Telecaster and

he really just made the thing sing. I thought he was fantastic. He had to

be, like, 21 or something and I was, like, 17. And I did something on my

guitar where we started playing this song and then we got into the

instrumental and I just basically went nuts.

And I think it was the first time it ever happened, and I just kept playing

and I just kept going and going and grinding and just pounding away at this

rhythmic thing and then exploring the little nuances of it. And I think we--I

don't know how many minutes it went on and on, and when I came off stage, the

guy walked up to me and said, `Where the hell did you learn how to do that?'

He said, `What are you doing?' And I said, `What do you mean, what am I

doing? It's the same thing I've been doing.' And he said, `Oh, no, no, no.

If--no, I don't know what you're doing,' you know, and he knew, like, 200,000

more chords than I did and all the scales and everything and he just said, `I

just don't know what you're doing.' He said, `What did you do?'

And at that point, you know, I realized, `Well, there's a place I can go,' and

I just kind of fell into it by accident and I think I've spent the rest of my

life trying to get there.

GROSS: Now can you compare that to singing? Is there a place vocally for you

like that?

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah, but I'm not a very good singer. And, you know, like, I

don't have real good pitch control and especially have trouble singing freely.

Like, I can sing a melody and I can sing words, and I can put them together

with chords and get a feeling going, but the way Otis Redding sang, you know,

that soulful, free-flowing expression, I have trouble with that. I have

trouble opening up enough to really open up my soul and let things go. I

really, you know--and when I try to do it, every once in a while I get there

and it kind of feels like that first guitar solo felt to me. But, you know,

when I try to go back, it's, like, `Oh, you're just trying to do the same

thing over again that you did before.' It's not like I'm entering a new

domain. It's like I'm copying something. So I still haven't figured out how

to get to that space.

GROSS: But I love your singing.

Mr. YOUNG: Well, thank you, and I'm trying.

GROSS: You know, I'm listening to your speaking voice and I'm thinking about

your singing voice in that, you know, you have a pretty big range singing and

you sing lower and you sing higher up, but your higher-up voice is, you know,

considerably higher, I think, than most of your speaking voice.

Mr. YOUNG: Well, I've been on the road here for a better part of a year,

so--and I just finished a show last night and--you know, about 150 miles away

from here. And I did a show the night before that about 300 miles away from

that. And I've driven to those places and driven back from the city and, you

know, so my voice is a lot lower right now than it naturally would be if I

wasn't on the road.

GROSS: Some of the images that you've used today are so good, like your image

about guitar playing and about, you know, going deeper down--I mean, just a

really nice image. And I was wondering--I know that your father was a

sportswriter. Do you think you were influenced at all languagewise being the

son of a writer?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, I think there's always that influence.

GROSS: Now, of course, there's your lyrics, too. I'm just thinking about...

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah.

GROSS: ...hearing you talk. But, I mean, you've written, you know, lyrics

throughout your whole career.

Mr. YOUNG: Well, you know, my dad wrote a lot of stories, and he...

GROSS: Fiction?

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah, fiction and non-fiction, but he did write a lot of fiction,

and he used to try to write a little bit every day, and I'm not like that. I

only try to write when I feel like writing, but if I feel like writing, I

don't care what else is going on. I won't do it. I will write, and I think

that's why I've written so many songs. If an idea comes to me out of nowhere,

I look at it like a gift. It's not a distraction. Everything else in the

room is a distraction. I don't care what it is. So in that way, I'm

committed to the muse. I roll with the muse. Wherever it goes, if it comes

to me, I'm going with it. That's what got me where I am today and that's what

made it so that I could create all these things and so that I could put all

these people to work that I have, and I have an affect on a lot of people.

And just all the things I've been able to do are all because of being faithful

to that one thing and realizing that all of this is all coming from somewhere

else, and you just have to be there and ready with open arms to take it in,

and then send it back out in a form that people can understand or people can

enjoy.

GROSS: Neil Young, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. YOUNG: Thank you.

BIANCULLI: Neil Young speaking with Terry Gross last year. His new acoustic

CD, "Prairie Wind," has just been released. "Prairie Wind" also includes a

DVD documenting the recording session. Here's another song from that CD.

(Soundbite of "Far From Home")

Mr. YOUNG: (Singing) When I was a growing boy and rocking on my daddy's

knee, Daddy took an old guitar and sang, "Bury Me On The Lone Prairie."(ph)

Uncle Bob sat at the piano. My girl cousins sang harmony. Those were the

good old family times that left a big mark on me.

Bury me out on the prairie where the buffalo used to roam, where the Canada

geese once filled the sky, and then I won't be far from home. Bury me out on

the prairie where the buffalo used to roam. You won't have to shed a tear for

me, 'cause then I won't be far from home.

BIANCULLI: That's "Far From Home" from the new Neil Young CD "Prairie Wind."

Coming up, David Edelstein reviews "Capote," the new film biography of the

writer Truman Capote. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Film "Capote," based on Truman Capote's life

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

In 1959, four members of a Kansas family were murdered in their home and the

capture, conviction and execution of their killers became the basis of Truman

Capote's 1965 best-seller "In Cold Blood." Capote died in 1984 at the age of

59 never having completed another major work. Film critic David Edelstein

says the new film suggests why.

DAVID EDELSTEIN reporting:

"Capote" tells the story behind the story of the writing of "In Cold Blood"

through the prism of Janet Malcolm's "The Journalist and The Murderer."

That brilliant book-length essay on the journalist's inevitable betrayal of

his or her subject begins with the provocative and I think madly overheated

assertion that, quote, "Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of

himself to notice what is going on knows what he does is morally

indefensible."

As directed by Bennett Miller and written by Dan Futterman, who cites Malcolm

in interviews, the grim story of Truman Capote and his seminal non-fiction

masterpiece becomes a tale of duplicity and self-loathing, of the loss of a

writer's soul and the beginning of the end of his artistry. The title

character, played by Philip Seymour Hoffman, is the droll dandy that many of

us remember from Capote's TV appearances in the '60s and '70s. He's the

oddball homosexual Southerner with a voice that suggests at once suckling and

conniving, the voice of a baby mad scientist. A master manipulator, he speaks

so slowly that people have to stop and hang on every self-consciously dazzling

word. He has a cult in the boho salons of Manhattan and Brooklyn, but how

will his act play in Kansas?

That's where Capote heads in 1959 along with his doting friend, the novelist

Harper Lee, played by Catherine Keener, when he reads of the inexplicable

slaughter of an entire family, the Clutters, in their remote farmhouse.

Capote cuts a bizarre figure in the American heartland but he uses his

celebrity and the power of his magazine, The New Yorker, to open both official

doors and jail cells. It's in the latter that he develops a tender intimacy

with one of the Clutters' killers, Perry Smith, played by Clifton Collins Jr.

(Soundbite from "Capote")

Mr. CLIFTON COLLINS Jr.: (As Perry Smith) We're going to be able to use your

book for our case. You're right, we never got to raise an insanity plea. You

wrote how terrible the lawyers was.

Mr. PHILIP SEYMOUR HOFFMAN: (As Truman Capote) I haven't written a word yet.

Mr. COLLINS: (As Smith) Well, what have you been doing?

Mr. HOFFMAN: (As Capote) Research, talking to you.

Mr. COLLINS: (As Smith) All right.

Mr. HOFFMAN: (As Capote) I had hoped...

Mr. COLLINS: (As Smith) What are you calling it?

Mr. HOFFMAN: (As Capote) The book? I have no idea. Perry, if I'm going to

write about you, if I'm going to determine how to write about you, we need to

talk about why you're here and the murders that night at the Clutter house.

EDELSTEIN: Of course, Capote has started writing and has got his title. He

just doesn't plan to finish "In Cold Blood" until Smith and his cohort,

Richard Hickcock, have been hung. That must be the book's big finale. And

while Capote cares for Smith, maybe even adores him, he becomes desperate to

see him executed so he can finish.

Over the years it takes for the killers to exhaust their appeals, Capote's

inner conflict between his empathy and opportunism eats him alive. The movie

is slow and gets slower as it crawls to the big scene of Capote extracting

from Smith the story of the murders, presented here as a triumphant piece of

vampirism. It's powerful and eerie, but I think something's missing. Capote

and his work transcended that vampirism and "In Cold Blood" fostered more

understanding of why people kill than any book I know. I don't know how

Futterman and Bennett could have conveyed the depth and humanity of Capote's

writing on screen, but a film that ignores this alchemy of creation, that

presents the book only in the context of Capote's celebrity and Janet

Malcolm-esque exploitation, isn't telling the full story.

The distorted mirror image that Capote told friends he saw in Smith is more

talked about than dramatized, but the actors fill in much. As Smith, Collins

finds the perfect mixture of neediness and cunning. And Hoffman--talk about

alchemy. He's much bigger than Capote, but framed to look short. The first

few minutes, you're aware of the nightclub impersonation aspect, but Hoffman

reportedly listened to many tapes of Capote, and sometimes when gifted and

porous actors faithfully duplicate the stammers and pauses of their subjects,

the spirit enters into them.

Hoffman lays bare this whiny, wheedling, self-absorbed little man who

nonetheless could see more deeply than almost anyone alive, if only the movie

did more than hint at the genius behind what he saw.

BIANCULLI: David Edelstein is film critic for Slate.

(Credits)

BIANCULLI: For Terry Gross, I'm David Bianculli.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.