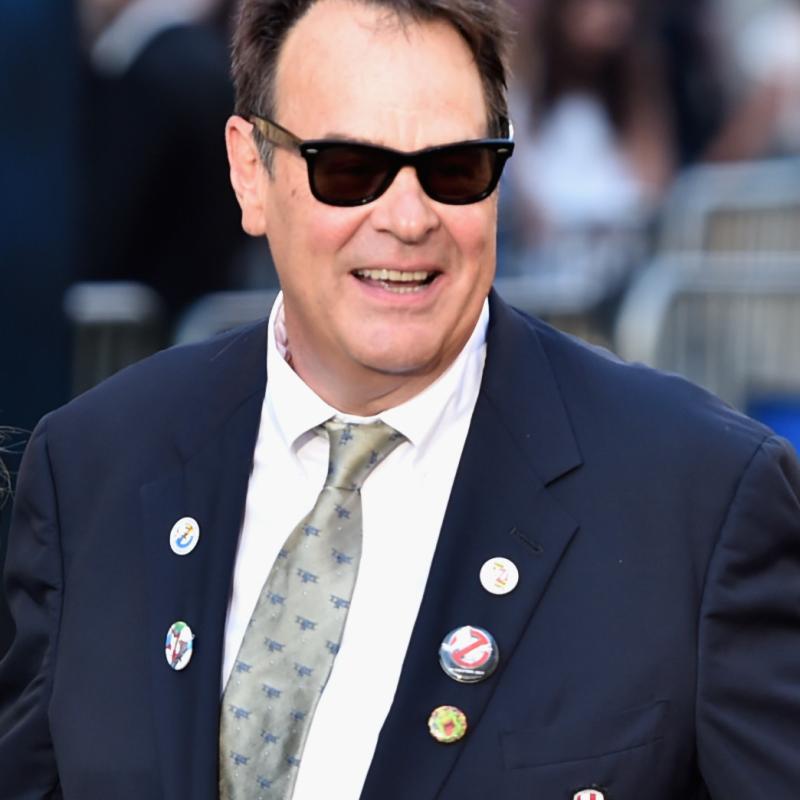

Dan Aykroyd, Still Full of the 'Blues'

After soaring to fame with Saturday Night Live, Dan Aykroyd built a solid film career. But he's still capitalizing on his early hit, The Blues Brothers (now available in a 25th-anniversary DVD). He serves on the board of the "House of Blues" restaurant and concert-venue franchise, and last year he published a book as his Blues Brothers alter-ego, Elwood, interviewing blues greats. (This interview was first broadcast on Nov. 22, 2004.)

Other segments from the episode on August 12, 2005

Transcript

DATE August 12, 2005 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Dan Aykroyd discusses his experiences as an actor,

musician, interviewer and author

DAVE DAVIES, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies, senior writer for the Philadelphia Daily

News, filling in for Terry Gross.

On today's FRESH AIR, an interview with Dan Aykroyd.

(Soundbite of "Everybody Needs Somebody to Love")

Mr. DAN AYKROYD: (As Elwood Blues) We're so glad to see so many of you

lovely people here tonight. And we would especially like to welcome all the

representatives of Illinois' law enforcement community, who have chosen to

join us here in the Palace Hotel Ballroom at this time. We do sincerely hope

you all enjoy the show. And please remember, people, that no matter who you

are and what you do to live, thrive and survive, there are still some things

that make us all the same. You, me, them, everybody. Everybody.

Mr. JOHN BELUSHI: (As Jake Blues) (Singing) Everybody needs somebody.

Everybody needs somebody to love, someone to love.

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Elwood) (Singing) Someone to love.

Mr. BELUSHI: (As Jake) (Singing) Sweetheart to miss.

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Elwood) (Singing) Sweetheart to miss.

Mr. BELUSHI: (As Jake) (Singing) Sugar to kiss.

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Elwood) (Singing) Sugar to kiss.

Mr. BELUSHI: (As Jake) (Singing) I need you, you, you. I need you, you, you.

I need you, you, you in the morning.

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Elwood) I need you, you, you...

Mr. BELUSHI: (As Jake) ...when my soul's on fire.

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Elwood) You, you, you.

Mr. BELUSHI: (As Jake) Sometimes I feel, I feel a little sad inside when my

baby mistreats me. I never, never, never have a place to hide. I need you.

DAVIES: That's "The Blues Brothers," with Dan Aykroyd as Elwood Blues and

John Belushi as his brother Jake. Their 1980 movie has just come out on a new

25th-anniversary edition DVD. Aykroyd and Belushi created their two blue-eyed

soul men for "Saturday Night Live," then built two movies around them. In the

second film, Jim Belushi took over the role for his late brother. Aykroyd

also developed a radio show called "The House of Blues Radio Hour" and has a

book of interviews from the program called "Elwood's Blues: Interviews with

the Blues Legends and Stars." The Blues Brothers' success led Aykroyd to

co-found the nightclub chain the House of Blues. He's busy these days opening

new House of Blues clubs in several cities.

(Soundbite of "The Blues Brothers")

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Elwood Blues) You know, people, when you do find somebody,

hold that woman, hold that man, love him, please him, squeeze her, please her.

Hold, squeeze and please that person. Give them all your love. Signify your

feelings with every kiss or caress. You know, it's so important to have that

special somebody to hold, kiss, miss, squeeze and please. Everybody needs

somebody. Everybody...

DAVIES: Aykroyd has appeared in dozens of films besides "The Blues Brothers,"

including "Ghostbusters," the "Coneheads," "Driving Miss Daisy," "Doctor

Detroit" and "Trading Places." Terry spoke with Dan Aykroyd last year.

TERRY GROSS, host:

How did you and Belushi start the whole Blues Brothers routine?

Mr. AYKROYD: In 1973, John came up to Canada to recruit for the "National

Lampoon Radio Hour." And I was in "Second City" with Gilda Radner and with

John Candy. And John came into Toronto and he joined us on the set of the

Second City stage, and we did an improv set, and then we went back to my very

famous speakeasy called the 505, which opened after 1:00 after the Liquor

Control Board of Ontario closed most of the bars in the province. We had a

bar at the corner of Queen and River at 505 Queen Street, and all the

streetcar drivers and cops from, like, outlying regions and waiters and

waitresses and dancers would come to drink.

And I had a record on by the Downchild Blues Band out of Toronto, Donnie

Walsh, an incredible seminal artist out of Canada. And John and I were

listening to it and John said, `What is this? This is a great record.' I

said, `Oh, it's just a local blues band.' `Blues, huh? Oh, I'm from Chicago.

I hear the blues now and again. But I'm into heavy metal,' he says. I said,

`Well, John, you show me heavy metal and I'll show you the blues.' So we

started to kind of talk about it and listen. And Howard Shore was there that

night. He's, of course, the great Oscar-winning composer of "The Lord of The

Rings" trilogy music; he was the original musical director on "Saturday Night

Live." And he was in Toronto at that time and had dropped by the bar, and he

said, `Yeah, you guys should start a band, and you could call it the Blues

Brothers.' And we just went bink, bink.

And we started to correspond--I didn't go back to New York with John. He had

managed to get Gilda to go back with him. But we kept in touch on the phone,

and we started to look at material and develop material. And we did our first

gig in New York in the Lone Star Cafe, and our backup band was Willie Nelson,

with Mickey Raphael, one of the greatest harmonica players ever. And Willie

understood what we were trying to do, like so many that came along and joined

us. They understood that, OK, these guys aren't the greatest musicians or

singers or dancers, but what they are are great front men and they love and

respect the music.

So the hat and glasses are from the John Lee Hooker album "House of the

Blues"; he wears those shades and that hat on the cover there. The suits, the

black jacket and thin tie and white shirts were because, you know, a lot of

artists in the '60s kind of, you know, who were progressive and maybe were

getting in trouble with the law like Lenny Bruce, wanted to look straight.

And so it was kind of trying to get that IRS look together to kind of fool the

straights was where that came from.

GROSS: When you were working at doing "The Blues Brothers" movies or, you

know, working with House of Blues or even working on "Saturday Night Live,"

did you ever feel like, in meeting some of the people who had been your idols

when you were coming of age, that you were now in the position of being `The

Man' because you might have been in the position of helping to, like,

negotiate the deal and they might be feeling that you weren't paying enough

and, you know, when you're negotiating deals with somebody or when, you know,

you're behind the--you know what I'm saying. So did you ever feel like

suddenly you were in, like, the side that you didn't want to be on?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, I always felt, you know, whatever artists we ever played

with or worked with or that were in the movies or records, that they never

were being paid enough, and I always tried on my own to kind of supplement

that. But what I felt more was that, you know, John and I, when we did the

Blues Brothers, we were in existence to serve these great artists and to, you

know, perhaps maybe, you know, reintroduce them to our audience. And we

always felt a great reverence for James Brown, Ray Charles, Aretha, and never

felt that we were their equal, but we felt that we were really in service to

their gift.

And I think that's why people like Steve Cropper and Duck Dunn and Tom Malone

and Al Rubin and Marini, you know, our great band that we had--I think that's

why they joined us, and they realized that, you know, we had a great reverence

and respect for the music. And that's why they were so behind us. Always

felt in service to these great artists, as I do feel today, like--when I was

back in Chicago, we were working on--I think it was--I guess it was "The Blues

Brothers" movie--Albert Collins came in to play at Wise Fools. And he pulled

up in his car, and he was unloading his amp and the drums, and I was sitting

waiting for him to go on stage, and I looked at him, and nobody was helping

him. And I got out there and basically was his roadie for the evening. And

that was the most satisfying--one of the most satisfying feelings I've ever

had, that I could tangibly really help this man get onstage and play his

music. And he didn't know who I was. He didn't know "Saturday Night Live" or

"Blues Brothers" or anything. I was just a guy who was helping him to pull

his equipment in out of the rain and to get onstage. And I really feel

honored that I was able to do that.

GROSS: What were the first records you bought? Can you remember?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, the first records, of course, were, you know, The Beatles

and the Stones. And then I think the seminal record for me was the East-West

record that Paul Butterfield did in the late '60s with Elvin Bishop and

Michael Bloomfield. And from then on, I began to go out and try to search the

bins in the record stores for blues artists and then started listening to John

Lee Hooker. And we had a tremendous booking agent in Ottawa, Canada, where I

grew up--that's the capital of that great, great nation--and my parents worked

for the government up there, and I was kind of a son of government workers up

there. And there was a club called Le Hibou which was right on Sussex Drive

near where the prime minister lives. And we had a booker there named Harvey

Glatt, and he brought in all of the great blues stars of the age so that, as a

teen-ager, I jammed behind Muddy Waters when S.P. Leary refused to take the

drum kit. And he said, `Is there anybody out there that's a drummer?' And I

walked up and I started to play, and Muddy turns to me and he goes, `Keep that

beat going, boy. You make Muddy feel good.' I mean, this was part of my

early exposure.

And then I saw Paul Butterfield and Charlie Musselwhite and, you know, all

these great players. And it was, I guess, just through the insight of this

guy who was, you know, booking for the college crowd up there. And then

listening to the black radio stations in Boston and Detroit and New York, this

was--you know, these were sort of all part of my exposures, I guess.

GROSS: So what was in your parents' record collection? What did they listen

to, and how did that affect what you liked or didn't like?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, my dad used to pore over the newspapers and look for

record collections that were used. So he would go and he'd see that some guy

in Ottawa or Hull or where we were living there would be selling a hundred

records, and he'd just go out and buy 'em all. So we were listening to

anything from Glenn Miller to Mario Lanza, lots of Broadway soundtracks and

stuff. But I think my father really influenced me when he started to get into

the Jack Hilton, Ray Noble, Freddy Gardner, English swing band music. That

was really something because, you know, the value of horns was there. And

then later, as I started to buy, of course, it was The Beatles and the Stones

and The Animals and then the Paul Butterfield record. But my dad was into the

swing band music, as many people were in Canada at that time.

GROSS: Now I read about you that you had a pretty strict Catholic upbringing,

that you went to Catholic school. Did...

Mr. AYKROYD: Seminary.

GROSS: Seminary. Whoa, OK. So you're growing up in Canada; you're going to

a seminary and listening to blues and rock 'n' roll and rhythm and blues.

Mr. AYKROYD: And seeing guys onstage in my high school imitating Mick

Jagger...

GROSS: Ri--OK.

Mr. AYKROYD: ...imitating The Animals, you know...

GROSS: OK. That's where I'm heading. Were you...

Mr. AYKROYD: Yeah.

GROSS: Did you--long before you became part of the Blues Brothers and you

developed this kind of alter ego for yourself, did you have a pose when you

were in high school? Did you want to be black? Did you want to be a blues

musician?

Mr. AYKROYD: I...

GROSS: Did you want to be somebody who you weren't and kind of take on that

pose in real life?

Mr. AYKROYD: Sure. I wanted to be Paul Butterfield and Charlie Musselwhite.

And I used to walk around in a long trench coat, a long brown trench coat with

shades, and I'd slick my hair back, and I'd try to find any little band up in

the bars up in the Gatineau and up in Ottawa and Hull and where I was living.

And I would get onstage with them, and they'd be country bands, and I would

turn to them and say, `Well, can you do it like this?' And I would kind of

show them a basic, you know, eight-, 10-, 12-bar blues pattern, and then we'd

just take off from there. And of course I was posing as Paul Butterfield.

Yeah, absolutely.

GROSS: And...

Mr. AYKROYD: And then my friend Derry O'Dwyer(ph), who is now a school

principal up in Cobourg, Ontario--he was pretending to be Eric Burdon. And I

had, you know, the math whiz in class in grade 11 was pretending to be Mick

Jagger. So everybody was posing, and it was all based on rock 'n' roll and

music and blues then, all of it.

GROSS: Did you sing then, or--I know you played drums.

Mr. AYKROYD: I played harp mostly...

GROSS: And harmonica. Yeah.

Mr. AYKROYD: ...and sang. Yeah. The drumming was sporadic but, you know, I

filled in for bands now and again when I was growing up.

GROSS: And were you using mostly your voice, or were you--did you almost have

a persona singing voice?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, back then you tried to kind of imitate the people that

were singing, so, you know (in different voice) and even today, I mean, you

know, when I sing, I try to, you know, get down and, you know, be someone

else. You know, you try to sing and try to (singing) Who do you love? Who do

you love? (In normal voice) I mean, of course you sing like the people that

you want to emulate and people that you admire.

GROSS: Every try singing like yourself?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, I have a pretty--you know, I mean, it's sort of a reedy

kind of voice. This record that Jimmy Belushi and I put out last year, which

made it to number one on the blues chart, "Have Love Will Travel," I'm

more close to my own voice on that than some of the other stuff we did as the

Blues Brothers, I guess. Yeah. But I've always kind of sung...

GROSS: I do have that right here. Do you want to pick something?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, yeah, the Junior Parker song "Driving Wheel." That's a

good cut off that record.

(Soundbite of "Driving Wheel")

Mr. AYKROYD: (Singing) My baby don't have to work. My baby don't have to

rob and steal. My baby don't have to work. My baby don't have to rob and

steal. I give that little girl everything she needs. I am her driving wheel.

She left me this morning, said she gonna be back soon. My baby left me this

morning, said she's gonna be back soon. Well, that'll have to be late Friday

evening or early Saturday afternoon.

DAVIES: We'll hear more from Dan Aykroyd after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

DAVIES: We're listening to Terry Gross' interview with Dan Aykroyd recorded

last year. A 25th-anniversary edition of his film "The Blues Brothers" has

just been released.

GROSS: Dan Aykroyd, what kind of acting did you do before the "Saturday Night

Live" era when you were still living in Canada?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, I did high school plays. And in college, I was a stage

manager with the Sock 'n' Buskin group at Carleton University, which is a

great school in Ottawa, Canada. I was a terrible stage manager 'cause I

wanted to be an actor. But the producers and directors of these shows had

sensed that, and they kind of let me come onstage. We did "Tom Paine"; I

played the king of France and a few other things in there. And I basically,

you know--just little stuff, did some guerrilla theater, some Ferlinghetti and

that type of stuff, you know, anything to kind of get out there and get

involved and have fun. And I gotta tell you, Terry, I mean, I have had fun.

My whole life, my whole professional life has been fun. I don't think really,

you know, I can--I don't really think I can call it work. It's just been

really, really fun.

GROSS: Now I read that you did some TV commercials before "Saturday Night

Live." Is that right?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, I was--I had a production company with Dave Thomas, who,

of course, is the genius...

GROSS: Oh.

Mr. AYKROYD: ...one of the geniuses behind "SCTV." We had a radio commercial

production company, and we did some radio and television commercials, you

know, in Canada when we were growing up.

GROSS: Well, you know, you've done--you did so many really funny commercial

parodies on "Saturday Night Live." Did you ever do the real thing? Did you

ever do the equivalent of, you know, the Bass-O-Matic or those Ronco

commercials?

Mr. AYKROYD: Yes.

GROSS: Really?

Mr. AYKROYD: Absolutely. Yeah, I...

GROSS: What did you do ads for?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, one of my first jobs in broadcasting was working for

City-TV in Toronto, which was this whole new concept in urban television that

really--basically today your news desks across America, Channel 7, 4 or 2,

wherever you want to be in network, with the graphics and the presence, the

seemingly sort of active presence of the newscaster--this is from Moses

Znaimer's City-TV. He basically changed the whole format and the whole

delivery of news in North America. And I worked for his station; I was a game

show announcer. And I also did, you know, the shock box announcing(ph), so I

actually had to do that fast rap stuff for, you know, car companies and beer

companies and all that. So, sure, I was actually doing it professionally when

I first started out. And I was hired by none other than Ivan Reitman. We

went on to do the "Ghostbusters" thing together.

GROSS: Wow. So you were doing the real thing before you did the parodies.

Mr. AYKROYD: I was. Yeah, I was a mailman in Toronto when I first moved

there. I knew I wanted to go to Toronto, work with Lorne Michaels again. I

had gone there to do a special with him when I was 19, went back to Carleton

University, couldn't concentrate--you know, I had to be in show

business--dropped out of school, much to the chagrin of my parents. I got a

job driving mail truck in Toronto, and then I shifted to the broadcasting.

And, yeah, I was a shock box announcer for about a year there with City-TV and

hired by Ivan Reitman, and recommended by Lorne. Lorne said, `You should hire

this kid.' So Lorne Michaels has been instrumental in my career from, you

know, basically age 17.

GROSS: Let me ask about one of the parody commercials you did, and this is a

terrific video compilation of your best--or some of your best sketches from

"Saturday Night Live." And this is the one for the Bass-O-Matic. It's like a

blender that turns fish into a delicious shake. Just...

Mr. AYKROYD: I think people remember. Yeah.

GROSS: Tell me how you came up with this...

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, my...

GROSS: ...and if relates to a real ad that you ever did.

Mr. AYKROYD: Oh, yeah. No, no, my aunt, the late Helene Goujean(ph)--she

was a lovely woman, my mother's sister. She was, in fact, the Julia Child of

Canada.

GROSS: Really?

Mr. AYKROYD: She had--yeah. She had a television show and a cuisine shop in

Montreal during the '60s. And she--I went to her house for lunch, and she was

a, you know, master gourmet chef, and she was very well known for it. She was

on the network, the TV up there. And she said she was making a fish soup.

And I saw--she dropped the whole fish into the blender. I said, `With the

bones and everything, you know?' And she said, `Oh, no, don't worry. The

bones--you pick the bones out like you were eating a fillet. Don't worry

about it.' And I never forgot that.

And then, you know, many years later I was sitting with Paul Simon and Lorne

Michaels and Elaine(ph), and Chevy and John and I were there. Belushi,

Simon--Paul Simon--me, Lorne and Chevy. And we're sitting there, you know,

and we were just kind of laughing over things, and I was thinking about that.

And, you know, we were eating a meal, and I thought, `Yeah, I got this idea

for, you know, a scene, you know, Bass-O-Matic.' And when I said that, Paul

Simon, you know, who's probably one of the most brilliant people ever in

entertainment, he started to really laugh. And it's hard to get Paul to

laugh, you know, because he's so intellectual, so smart. You know, you gotta

be at a certain level. When he started to snort, I said, `Man, I got

something. If I can make Paul laugh this easy'--and I went away and I wrote

the scene based upon that night and my aunt's real experience with the fish in

a blender.

And I remember a woman wrote me a letter; she was very upset that I would

change the molecular state of the fish from solid to liquid, you know, on

television. She was really, really upset about that. And I wrote her back

and I said, `Well, you know, this was actually the way that my aunt made fish

soup.'

GROSS: Well, let's hear Dan Aykroyd advertising the Bass-O-Matic on "Saturday

Night Live."

(Soundbite of "Saturday Night Live")

Mr. AYKROYD: How many times has this happened to you? You have a bass.

You're trying to find an exciting new way to prepare it for dinner. You could

scale the bass, remove the bass's tail, head and bones and serve the fish as

you would any other fish dinner. But why bother, now that you can use Robco's

amazing new kitchen tool, the Super Bass-O-Matic 76? Yes, fish eaters, the

days of troublesome scaling, cutting and gutting are over, because Super

Bass-O-Matic 76 is the tool that lets you use the whole bass with no fish

waste, without scaling, cutting or gutting. Here's how it works. Catch a

bass, remove the hook and drop the bass--that's the whole bass--into the Super

Bass-O-Matic 76. Now adjust the control dial so that that bass is blended

just the way you like it.

(Soundbite of blending noise, laughter)

Mr. AYKROYD: Yes, it's just that simple.

(Soundbite of laughter and applause)

Unidentified Woman: Wow, that's terrific bass.

DAVIES: Dan Aykroyd spoke last year with Terry Gross. He'll be back in the

second half of the show. Here's more from "The Blues Brothers." I'm Dave

Davies and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of "Rawhide" from "The Blues Brothers")

Mr. AYKROYD AND Mr. BELUSHI: (Singing) Rollin', rollin', rollin'. Rollin',

rollin', rollin'. Rollin', rollin,' rollin'. Rollin', rollin', rollin.'

Rawhide.

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Elwood) Rollin', rollin', rollin' though the streets are

swollen, keep them doggies rollin'. Rawhide. Rain and wind and weather, hell

bent for leather, wishin' my gal was by my side.

Mr. BELUSHI: (As Jake) All the things I'm missin', good meals, love and

kissin', are waiting at the end of my ride.

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Elwood) (Singing) Move 'em on.

Mr. BELUSHI: (As Jake) (Signing) Head 'em up.

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Elwood) (Singing) Head 'em up.

Mr. BELUSHI: (As Jake) (Singing) Move 'em on.

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Elwood) (Singing) Move 'em up.

Mr. BELUSHI: (As Jake) (Singing) Head 'em up.

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Elwood) (Singing) Rawhide. Cut 'em out.

Mr. BELUSHI: (As Jake) (Singing) Ride 'em in.

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Elwood) (Singing) Ride 'em in.

Mr. BELUSHI: (As Jake) (Singing) Cut 'em out.

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Elwood) (Singing) Cut 'em out. Ride 'em in, Rawhide.

(Credits)

DAVIES: Coming up, Dan Aykroyd talks about his days with John Belushi.

There's a new 25th-anniversary edition DVD of their film "The Blues Brothers."

Also, David Edelstein reviews the new film "Junebug."

(Soundbite of music)

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies sitting in for Terry Gross.

Let's get back to her interview with Dan Aykroyd. He created "The Blues

Brothers" with John Belushi, and a new 25th anniversary DVD of their 1980

movie has just been released. Aykroyd co-created another pair of famous

brothers for "Saturday Night Live," the Czech Brothers, the Wild & Crazy Guys,

featuring Steve Martin as the other brother.

(Soundbite of "Saturday Night Live"; laughter)

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Czech brother) Ah, that ...(unintelligible) bar was really

something tonight. It was no difficulty to see many swinging Americans

enjoying each other a great deal.

Mr. STEVE MARTIN: (As Czech brother) And here is a thing I will tell you.

The two most swinging foxes have the hots on for us and are coming here

tonight to let us hold on to their big American breasts.

(Soundbite of laughter, cheers and applause)

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Czech brother) Why not? There's nothing preventing them.

After all, there's no other pair of Czech brothers who cruise and swing so

successfully in tight slacks.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARTIN: (As Czech brother) We are two wild and crazy guys!

(Soundbite of laughter, cheers and applause)

GROSS: I hope you don't mind talking about this because I'm sure you've been

asked so much. But the sketch that you did several times with Steve Martin,

the Wild & Crazy Guys, the two...

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Czech brother) I don't mind, Terry. It's all right.

GROSS: Great.

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Czech brother) Please. I enjoy talking about these great,

great times. And you, as an American female, should know I am no threat to

you. I am so distant from you now.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. AYKROYD: (As Czech brother) But if you were close to me, maybe then you

might have to fear what I would do.

GROSS: How did you come up with the characters?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, Steve had this guy called sort of the European continental

character. He was very suave and very continental. And then I had this, you

know, Czech engineer who had moved to New York City and was kind of

disoriented in the culture. So we blended his character and my character and

came up with the Wild & Crazy Guys.

GROSS: Well, who had you observed that inspired this character, who thinks

he's a real, like, American swinger, and he's just...

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, mostly...

GROSS: He gets--yeah.

Mr. AYKROYD: ...it was guys I met in bars over here, you know? The guy who

told me the story about running from the tanks--you know, he was a Czech, you

know, immigrant, and he told me about running from--you know, during the

Dubcek era running from the Soviet tanks. And I was just rapt and enraptured

by his story here, you know--and how, as a student, he'd challenged the tanks

and ran from the--(mimicking Czech man) `I ran from the tanks, and here I'm in

New York.' And, I mean, it was sort of a--you know, kind of a real swinger

character that I met in a bar. So I don't know where he is now, what his name

is, but he's definitely responsible for me starting to originate that

character.

GROSS: What did he tell you about the foxes?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, you know, he was--his whole modus operandi was the gold

chains and the polyester shirts and, you know, the whole thing about the--you

know, his existence was to try to get some great foxes to come home with him.

And, you know, I wasn't into the swinging scene, but I was, you know, in New

York, kind of single and living at that time. And he was just one of these

characters I was just--made me agog: `My, do they really exist? I mean, how

could a woman even talk to this guy for more than 10 minutes?' You know,

you'd just want to run from him. But I didn't. I sat there and I pumped him

for whatever he had to do. I think he was selling plumbing fixtures at the

time. He was like a very sophisticated--in terms of his education, he was an

architect and an engineer, but he was selling plumbing fixtures. And he was

really fascinating. And I just--you know, it was one night in a bar that I

met this guy, and from that, you know, you get the wild and crazy guy.

GROSS: Can I ask you about the character you came up with of Fred Garvin:

Male Prostitute?

Mr. AYKROYD: The Fred Garvin: Male Prostitute came solely out of I was

living in New York with Rosie Schuster, who was one of the great writers on

the show, and we had a romance. We were living together as, you know, a kind

of, I guess, unmarried couple or whatever you want to call it. People do that

in this country, don't they? And we were living together, and I used to do

that at home to try to--as sort of--as foreplay. And from that, you know...

GROSS: Describe the character, in case any of our listeners are not familiar

with it.

Mr. AYKROYD: (Using Fred Garvin voice) Well, Fred, he's a pretty

straightforward guy, who's got his--wears his sexuality on his sleeve, ready

to please a woman any way he can. But he's got certain physical infirmities

that prevent him from--oh, eeh, ah--hernias and all that kind of thing.

And I would do this, and she would laugh and just, you know--and then we

decided, `We gotta write this up.' So we wrote it up for Margot Kidder. So

Rosie and I wrote that together based upon us just living together and kind of

laughing because, you know, I mean, look at me. You know, I'm not Ramon

Novarro.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. AYKROYD: And so I made up for it with humor. And...

GROSS: Well, it's just really funny because it's like a male prostitute, but

the guy looks incredibly straight and square.

Mr. AYKROYD: (Using Fred Garvin voice) Well, we always wears the plaid...

GROSS: Yeah, he's got the plaid jacket.

Mr. AYKROYD: (Using Fred Garvin voice) Yeah, he wears the Austrian hat with,

yeah, the glasses and the shirt. Absolutely, yeah. But there's no--hey,

Terry, let me tell you right now, give it a whirl. Give it a whirl because

you might enjoy what you don't see.

GROSS: Did you ever laugh uncontrollably during a sketch and not--you know,

and kind of lose what you were supposed to be doing?

Mr. AYKROYD: I--no, I was--we really--John and myself and Billy, we

really--that was something at "Second City" that we--we were really taught not

to do that because you don't want to break the integrity of the scene, and

that was really important to us. And that discipline carried over to

"Saturday Night Live." And I was not one of the ones that broke up. Yeah, I

mean, later on we used to see people do it and that, but it was something that

John and Billy and I really didn't--you know, we didn't like it when it

happened.

I think during the Nerds, where I'm the fridge doctor(ph) there and I come

over, and, you know, Billy's there with Gilda, they were cracking up, and I

can understand why they were cracking up. But, you know, it was something we

prided ourselves in not doing. If we could prevent ourselves from cracking

up, we really prided ourselves. And after, like, a scene or the show, we'd

go, `Well, boy, that was tough to get through that one,' because, you know,

we--the temptation was there to just laugh at your fellow performers. But I

think the "Second City" training really, really lasted.

GROSS: How did you know--like, at what point did you figure out that you

could do voices?

Mr. AYKROYD: Very early. About three years old, I was imitating the

announcers on TV. And my dad cut off the top of a hockey stick and tied some

tape around it and put a cord on the bottom and gave me, you know, a fake

microphone when I was four years old. And, you know, of course, in primary

school and high school, I imitated all the teachers. And then I met guys who

could imitate the teachers better than me, and then we sort of formed, you

know, these imitation squads. And, you know, my grade 11 math teacher, Father

Paul Baxter, God rest his soul--I was not one of his favorite students--there

were 10 of us that did him. And we would have--and one time we all came

dressed as him to school in the white lab coat with the little Coke-bottle

glasses. And, like, he had kind of a backward walk. He kind of wheeled back

to the blackboard. And he had this voice like this, just (mimics Baxter),

`OK, jokers, smarten up,' you know? And that's where it all really started.

And then it was 10 of us doing him, and, you know, he got a little amusement

out of it, but it didn't last long.

DAVIES: Dan Aykroyd speaking last year with Terry Gross. We'll hear more

after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

DAVIES: Let's get back to Terry's interview with Dan Aykroyd. A 25th

anniversary edition of his film "The Blues Brothers" has just been released.

GROSS: I don't know if this happens to you, but sometimes when I'm preparing

an interview, I'll read something about someone, and I'm not sure if they

really said that or if it's really true 'cause it sometimes isn't. So let me

read you something that I read that you had said, and you can tell me if it's

true. And if it is true and it's too personal, you can tell me that as well.

But I read that when you were 12, you were diagnosed as schizophrenic and that

you heard voices in your head and that you had to kind of keep that under

control.

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, it was more of a Tourette's thing than schizophrenia. I

was analyzed as Tourette's and Asperger's, which I still have a little bit

today. You know, I mean, I grew up being pulled one way by my mother, who was

very, very strict, and then being relaxed by my father, who was very passive.

And I had the Tourette's pretty badly there, and I went to a therapist about

it and, at 12 years old, was able to have the luxury of sitting down with a

therapist and talking through all kinds of things: books and music. And she

was quite influential in kind of evening me out.

Now back then, you know, of course--now today, you know, they just give kids

pills, but back then we didn't have the benefit of all the sophisticated

medication. Whether it works or not, I don't know. I think time will tell on

that. But it was not so much--I think when I said that, I was kind of going

to the extreme. It wasn't so much the schizophrenia part of it, but it was

the Tourette's-Asperger's, which can be associated with hallucinogenic voices

and that. And I still have a little touch of that today, but, you know, I've

been able to kind of defeat it without pharmaceutical medication. And I just

find, in my research and reading today, that there's a lot of people who have

this kind of mild condition. And some of them get over it, and some of them

it spins out where it affects them quite negatively. I don't...

GROSS: If you don't mind my asking, what were some of the symptoms when you

were 12? And were these things that you had to fight against to do the

kind...

Mr. AYKROYD: Yeah, mostly...

GROSS: ...of acting and writing you wanted to do, or did they feed that it

any way?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, it was mostly physical ticks, you know, and nervousness

kind of thing, that kind of thing and, you know, like grunting and ticks and,

you know, kind of the classic Tourette's type syndrome, that type of thing.

But by the time I was 14, it was allayed, and I really haven't had too much

occurrence, except on the Asperger's side, where I have a fascination with

police and I always have to have a badge with me. You know, there's this guy

in New York who has radical...

GROSS: It's--yeah, go ahead.

Mr. AYKROYD: ...Asperger's. He is a guy who goes down into the subway, and he

pretends to be a motorman, and he gets on the trains in uniform and drives the

subway.

GROSS: Really?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, you know, that's--yeah. That's a radical form of

Asperger's. Well, me, I have a fascination with law enforcement and the

police. I guess my grandfather was a Mountie and that. So, you know, if I

don't have a badge on me, I feel naked.

GROSS: Well, I can't tell if you're kidding or not.

Mr. AYKROYD: And that's it. No, no, it's true.

GROSS: I know you studied criminology when you were in college.

Mr. AYKROYD: I did. I studied criminology. I had a great professor there.

And that study of criminology really helped me when I wrote "The Blues

Brothers" 'cause the Blues Brothers were classic recidivists, could never

stay out of trouble, always looking for, you know, borderline sociopathic

hedonists. And I wrote papers on motorcycle outlaw clubs. I wrote papers on

the Detroit Mafia. I wrote papers in college--and when it came time to write

"The Blues Brothers," I was well-armed with criminological terms and knowledge

from my great professor, Professor Hatt(ph), at Carleton University.

GROSS: So have you broken the law yourself, outside of speeding tickets?

Mr. AYKROYD: I was popped for marijuana possession in Marseilles, Illinois,

oh, jeez--God, it's so long ago now. You know, I had a--I smoked it 'cause I

had a little problem with the back there. And I smoked it because it had the

effect of adding vasodilation to the bottom of the back. And so the cop

stopped me at a stop sign, and he said--you know, he plucked out the bag and

said, `What's this?' And I said, `Well, it's just a little pot to help me

drive across country.' He said, `Wow, I did all these--I used to do acid,' he

said. `I did acid and all this. Drugs are bad, drugs are bad.' And he took

me in and we sat down, and I said, `I'd like to see what you have in your

drawer.' And I looked in the drawer, and they had, really, much better stuff

than I was carrying.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. AYKROYD: And I said, `Can we trade?' And he said no. And it turned out

to be quite a nice evening. I talked with the young chief of police there,

and he said, `Ah, we see this stuff all the time.' I said, `What's going to

happen to me?' He said, `Ah, you'll get a $50 fine, and you won't even have

to pay it. I mean, God, you know'--so I gave it up.

But what was quite alarming was I was driving across country, and it was on

"Dan Rather" that night on the CB--you know, `Partner of John Belushi popped

for marijuana.' And then I was so afraid and so paranoid. I kept hearing over

the radio, you know, `Dan Aykroyd popped for possession of marijuana and

arrested,' and all that. I didn't know where to go. So where do I go? I ran

to Hunter Thompson's Colorado estate, and I said, `Hunter, Hunter, you know,

they'--and he said, `Oh, forget it. You should've had speed, you should've

had pills, you had all kinds of stuff. Come on in. Sit down.' I had a

shotgun in the trunk; I had a riot shotgun, which luckily I had broken into

two pieces. So when the cops searched my car, they saw I was a safe, you

know, citizen and all that. And you know what? He still has that gun today

'cause I said, `I didn't want to drive to California with that.' And so he's

still got that shotgun today. But, otherwise, other than that one arrest

there, nah, pretty much straight, legal.

GROSS: When you became part of "Saturday Night Live" and you had this really

talented young cast suddenly becoming famous and wealthy and having access...

Mr. AYKROYD: Not so wealthy. No, we didn't get wealthy.

GROSS: Not so wealthy? OK.

Mr. AYKROYD: No, no. No.

GROSS: But having...

Mr. AYKROYD: It was 275 a week.

GROSS: Oh, wow. OK.

Mr. AYKROYD: There was no wealth on "SNL."

GROSS: OK.

Mr. AYKROYD: The wealth came later.

GROSS: But, still, it was kind of fame and the kind of power that fame brings

and affairs and access to drugs probably.

Mr. AYKROYD: Yeah.

GROSS: I mean, you know, some people don't get through that very well is, I

guess, what I'm leading to.

Mr. AYKROYD: No. No...

GROSS: You seem to have gotten through it pretty well.

Mr. AYKROYD: ...John didn't.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. AYKROYD: John didn't get through it.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. AYKROYD: And many other of my friends didn't get through it. I--the

most valuable aspect of it was the creative satisfaction, really, of being

able to go out and write something and have it produced that next week or

that--you know, or at the end of that week. That was really the value of it.

You know, as far as the coke and the powders and the pills, I never was much

into that. As I say, you know, I had a little smoke and that, but more--I

don't know. I was focused more on the creative satisfaction of it than

anything else. And, you know, some of my compatriots, they were given the

means to go to these extreme pleasures, and they did. And it cost them

dearly. I warned them. I warned Chris Farley and I warned John and I warned

River Phoenix. I warned them all. I said, you know, `These are lethal

substances, and, you know, you gotta moderate.' But, you know, these were all

captains of their own ships. You can only suggest and try to influence. You

can't change behavior, you know, if these people have control of their own

lives and destinies and are not going to yield that control. So...

GROSS: When you would warn Belushi, who was such a close friend of yours...

Mr. AYKROYD: Oh, how about flushing vials down the toilet? How about, you

know, scraping, you know, things off the dresser? How about just destroying

powders? How about intercepting dealers? How about watering it down? How

about, you know, trying to get him to smoke a joint instead of do a line.

All, I mean, actively--I mean, Judy and I were totally and actively involved

in trying to deflect, you know, these people who wanted to serve him, these

sycophants who wanted to serve him. You know, we really took an active--and I

think we kept him alive maybe longer than he might have--you know, longer than

he might have been.

GROSS: And, in return, would he get angry with you?

Mr. AYKROYD: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. Oh, are you kidding me? You flush a vial

down the toilet, yeah, you know, he'd be crazy, crazy. And then, you know,

you'd just have to calm him down and take him for a walk and, you know--a lot

of baby-sitting there, a lot of baby-sitting, which I'm finished with now. I

ain't going to do that for anybody anymore, you know.

GROSS: How did you know then, like, what the right thing to do was and how

far to go?

Mr. AYKROYD: Well, the right thing--when you see these dealers, you know,

trying to please him for no money and stuff, I mean, I took people aside and

said, `You love this guy? You love his work? Well, don't destroy him. You

know, come on. You want to be his friend, keep this stuff away.' And, you

know, I remember taking out there--I remember Duck Dunn when we were doing

"The Blues Brothers" movie. You know Duck Dunn was the great bass player for

Stax/Volt. He was in our band, and he's still today one of the greatest

players. We were in The Alley at our club across from "Second City," the old

sneak joint where we had our bar, where we used to celebrate after shooting

"The Blues Brothers" movie at night. We had so much night shift there. And a

dealer came by, and Duck Dunn took out his belt to him and whipped that guy

all the way to the sidewalk. And I love that. That was beautiful, just

beautiful, because he knew the guy was coming to do John harm. That was great

enforcement right there.

GROSS: Must have been tough to remain really close friends with Belushi when

you were...

Mr. AYKROYD: Never.

GROSS: ...heading in such different directions.

Mr. AYKROYD: Never tough.

GROSS: No?

Mr. AYKROYD: No, we were always friends. That was no problem. It was tough

to put up with some of the stuff, you know, that, you know, he was doing and

that.

GROSS: Are you writing now?

Mr. AYKROYD: Not writing too much anymore, no. I'm only sort of focused

right now on our House of Blues. We're the third-largest concert business in

North America now, next to Clear Channel and AEG, the radio station on 200

stations almost now--a radio...

GROSS: Did you expect this, that this is what you would be doing?

Mr. AYKROYD: I never thought that "The Blues Brothers" would lead to an

actual tangible bricks-and-mortar institution, you know. I never thought

that. And I'll tell you, every time I walk into one of those places, I think

of John. And every time I walk into one of those places, I say, `John, man,

you know, we built this place for you.' He would have loved it.

GROSS: Dan Aykroyd, it's just been great to talk with you. Thank you so very

much.

Mr. AYKROYD: Thank you, Terry. I'm a great fan. And as I say, you know,

FRESH AIR and your show is my favorite radio to be stopped on the New York

state--by troopers to.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. AYKROYD: So next time a trooper stops me, I'll say, `Can we stop and

listen to Terry for a second?' And I'll get him in the car with me.

GROSS: Thank you so much.

Mr. AYKROYD: Take care.

DAVIES: Dan Aykroyd speaking last year with Terry Gross. A 25th anniversary

edition of his film "The Blues Brothers" has just been released. Here's the

Blues Brothers with Ray Charles.

(Soundbite of "Shake a Tail Feather")

Mr. RAY CHARLES: (Singing) Well, I heard about the fellow you've been

dancin' with all over the neighborhood. So why didn't you ask me, baby?

Didn't you think I could? Well, I know that the boogaloo is outta sight. But

to shake a leisure thing tonight, would it happen to me and you, baby? I

wanna show you how to do it right. Do it right. Uh-huh. Do it right. Do it

right. Do it right. Do it right. Ohhh! Twist it! Shake it, shake it,

shake it, shake it, baby! Here we go loop di loo! Shake it out, baby!

DAVIES: Coming up, David Edelstein on the new film "Junebug." This is FRESH

AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

Unidentified Man: (Singing in foreign language)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: New culture clash comedy drama "Junebug"

DAVE DAVIES, host:

A new culture clash comedy drama "Junebug" won a special jury prize for

actress Amy Adams at this year's Sundance Film Festival. It opens in major

cities this month. Our film critic David Edelstein has a review.

DAVID EDELSTEIN reporting:

"Junebug" is one of the most unresolved movies I've ever seen. It's a sort of

comedy and very entertaining, but it's full of dissonances, and in the end,

it's devastating. On occasion, the direction seems out of synch with the

script. Yet its disjunctions are what make it so tantalizing. It pricks you

in all kinds of places you can't put your finger on.

The script is by Angus MacLachlan, who's a playwright with a playwright's love

of symbolism. There are echoes of Pinter's "The Homecoming" and Sam Shepard's

"Buried Child," both about a prodigal son's return with a new wife and the

psychosexual feeling that bubbles up from the family's sub-basement. The

setting of "Junebug" is rural North Carolina, the childhood home of George

played by Alessandro Novelli.

I'm not sure what George does, only that he left for Chicago and married,

after a whirlwind courtship, a worldly, ambitious and gorgeous gallery owner

Madeleine played by Embeth Davidtz. Madeleine has staked her gallery's

identity on outsider art, which brings her to a very strange painter played by

Frank Hoyt Taylor in North Carolina. He does big, bloody Goyaesque Civil War

canvases. He also lives close to George's family who Madeleine has never met.

She gets off on the wrong foot by calling George's mother, Peg, Pat. But Peg,

who's played with scary intensity by Celia Weston, wouldn't have liked her

anyway for keeping George from coming home. She's not encouraged by George's

father Eugene played by Scott Wilson. But this decent, humble, barely

articulate man is a bystander. The younger brother Johnny played by Benjamin

McKenzie from "The O.C." measures himself against George and can't even bear

to be in the same room. Most vivid is Johnny's very pregnant wife Ashley

played by Amy Adams. Before Madeleine even arrives, Ashley knows she'll be

thinner and more beautiful. She's so threatened, she goes to the opposite

extreme from hate. She develops a huge sisterly crush on Madeleine. Hear for

yourself.

(Soundbite of "Junebug")

Ms. AMY ADAMS: (As Ashley) Are you wearing any makeup, 'cause you could wear

more if you wanted to, you're so tall? I'm fair. But I like to experiment

with a lot of different looks. Were you born in Chicago? I was born right

here. I lived here my whole life. My favorite animal is the meerkat. Do you

know what they are? They're so cute. Oh, I've got this little charm bracelet

with meerkats on it. Do you have lots of boyfriends? I bet you did. Did you

ever try out for cheerleading or anything? I tried out, but I didn't make it.

Ms. EMBETH DAVIS: (As Madeleine) I was born in Japan.

Ms. ADAMS: (As Ashley) You were not.

Ms. DAVIS: (As Madeleine) My father was in the diplomatic service, and then

we moved to Africa and then to Washington, DC, for a short while and then back

to Africa and then to Chicago.

Ms. ADAMS: (As Ashley) Wow. What kind of things did you like to do when you

were a little girl? Like, what type of things?

Ms. DAVIS: (As Madeleine) Oh, reading and horseback riding.

Ms. ADAMS: (As Ashley) At the same time?

Ms. DAVIS: (As Madeleine) No, I never tried it at the same time.

(Soundbite of laughter)

EDELSTEIN: Ashley becomes the emotional center, not only because the role is

superb, but because Adams, who was wonderful as the gullible Southern would-be

bride of con man Leo DiCaprio in "Catch Me If You Can," is luminous and

heartbreaking.

"Junebug" has a scheme that's a little creepy, maybe even misogynistic. Is

the city sophisticate Madeleine the protagonist or the villain or both? She's

madly flirtatious with George's brother and father. She has audible sex in

the future baby's nursery. She preys on the Southern culture without

beginning to understand it. In the script's most heavy-handed touch, she has

to make a moral choice between pursuing her private ambition or going to the

hospital to be with her sister-in-law giving birth. It shouldn't really be an

either/or issue, but here, it has momentous weight.

Although Madeleine stands for all that's chaotic and shallow, you don't hate

her, because Embeth Davidtz has too much buoyancy, and because Madeleine's

actions are instinctive and unconscious, like everyone else's. And is keeping

George away a good or bad thing? Depends on your perspective. When Madeleine

hears George sing a hymn sublimely at a church supper, she's enraptured and

freaked out by the uncompromising faith in which he was raised.

Director Morrison adds his own layer. The sound drops away. The talking

stops. We get images of the clean, tasteful home and cared-for landscapes.

Yet the plainness of this Southern setting is deeply mysterious. Underneath

the order and hospitality, there's something else, that backwoods painter's

canvases are full of violent, racist, sexual envy of an anger toward the North

and the big cities that's woven into the social fabric.

"Junebug" is full of, quote, "quirky material" handled in the least quirky way

imaginable. The editing is quick and arhythmic, and it gives this sometimes

too-well-carpentered material a haunting spaciousness. I had issues with the

movie. But after seeing it twice and thinking about it obsessively, I can

only say, `Let "Junebug" bug you, too.'

DAVIES: David Edelstein is film critic for the online magazine Slate.

(Credits)

DAVIES: For Terry Gross, I'm Dave Davies.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.