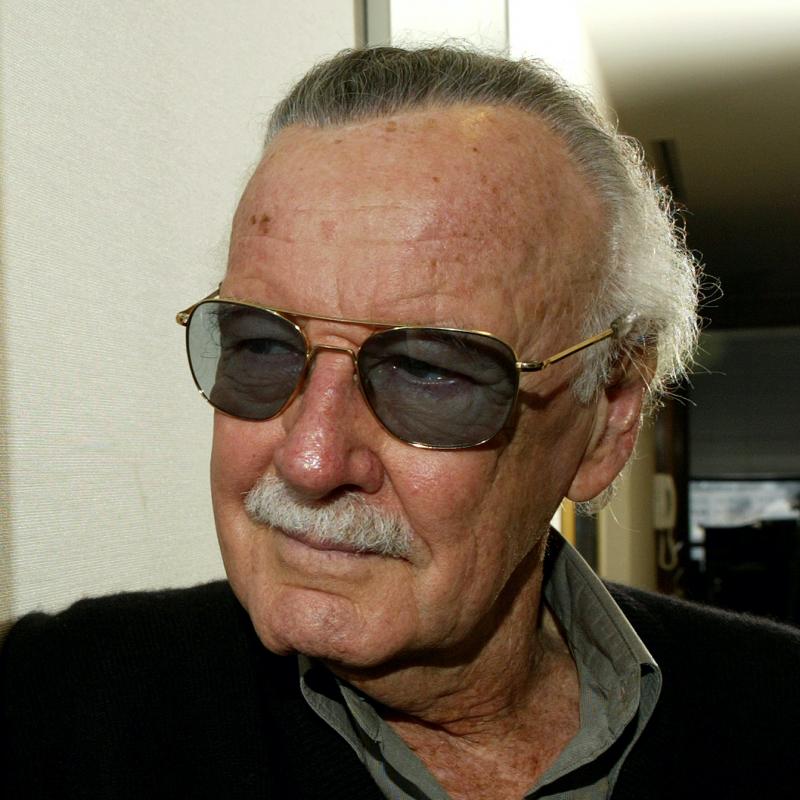

Comic Book Writer Stan Lee

Comic book writer Stan Lee. He was the leading creative force behind the rise of Marvel Comics and is responsible for many of the best-known comic book heroes. Forty years ago, he co-created the character Spider-Man. He also helped create The X-Men, The Fantastic Four and The Incredible Hulk. He is now Chairman Emeritus of Marvel Enterprises, and is executive producer of the new movie, Spider-Man. It stars Tobey Maguire, Willem Dafoe and Kirsten Dunst. His new book is called Excelsior! The Amazing Life of Stan Lee.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on June 4, 2002

Transcript

DATE June 4, 2002 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Stan Lee talks about his career and the creation of

Spider-Man

BARBARA BOGAEV, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Barbara Bogaev, in for Terry Gross.

(Soundbite from "Spider-Man")

Unidentified Man: With great power comes great responsibility.

Mr. TOBEY MAGUIRE (As Peter Parker): This is my gift.

Unidentified Woman: Wow.

Mr. MAGUIRE: It is my curse.

Unidentified Woman: Who are you?

Mr. MAGUIRE: Who am I? I'm Spider-Man.

BOGAEV: And that's from the new feature film "Spider-Man," starring Tobey

Maguire, directed by Sam Raimi and based on the Marvel comic book character

co-created by my guest, Stan Lee. Starting in the 1940s, Stan Lee served as

head writer, editorial and art director, publisher and chairman of Marvel

Comics. He's now chairman emeritus of the company. Lee's superheroes were

distinguished by their psychological complexity. They were burdened with

self-doubt and existential angst. They include The Fantastic Four, X-Men, Dr.

Strange the Mystic Magician(ph) and The Incredible Hulk. Now in his 80s, Lee

continues a full schedule of work projects, including films and TV series of

his characters. He's the executive producer of the new "Spider-Man" film, and

of an Incredible Hulk film, directed by Ang Lee, which is due out next summer.

And Lee has just written a new memoir called "Excelsior: The Amazing Life of

Stan Lee." I asked Stan Lee about the origins of the Spider-Man character

Peter Parker, whether he first came up with the idea for a superhero who could

climb walls or one that was a geeky teen.

Mr. STAN LEE: Well, I think the geek part came first. I decided I wanted

somebody who every one of the readers could identify with because I think

every teen-ager thinks of himself or herself as somewhat geekish at some time

or other. Most teen-agers are somewhat insecure and shy and inhibited and

introverted. So I figured a hero like that would be very empathetic to the

readers.

BOGAEV: So in that way, was he kind of a reaction to superheroes like

Superman, who was so stiff and proper?

Mr. LEE: I guess you might say so. Up until Spider-Man and some of the other

characters that we did at Marvel, I always felt most superheroes were

really--they were two-dimensional or almost one-dimensional. I mean, they

were just good guys who went out to fight the bad guys. And you didn't really

know much more than that about them. They had virtually no private lives. It

was just a case of, `Oh, somebody's committing a crime. I'd better become

whoever my alter ego is and go get them.'

BOGAEV: So how did the spider element come in?

Mr. LEE: Well, with every new superhero, you have to have a new superpower

because, as I'm sure you're aware, the superpower is what makes them

superheroes rather than regular heroes. And we, of course, specialized in

superheroes. I had already done a book called The Fantastic Four, and in that

book I had a girl who was invisible, a man who could stretch any part of his

body, a fellow who could burst into flame and fly, and somebody who was one of

the strongest people on Earth at the time. And I was figuring, or I was

trying to figure, `What other power can I give somebody?' And I saw a fly

crawling on a wall. Now I've said this so often it might even be true. I

can't even remember anymore, but I saw this fly crawling on a wall and I said,

`Gee, wouldn't it be something if a hero could stick to walls and move on them

like an insect?' And that's how it happened. And lo, a legend was born.

BOGAEV: But why wasn't he Insect-Man or ...(unintelligible)?

Mr. LEE: As a matter of fact, he almost was because, having decided that was

the superpower I wanted to give him, I next had to come up with a name. So I

began to think--Insect-Man, Mosquito-Man, Gnat-Man. I mean, anything I could

think of. None of them sounded right. I finally got to Spider-Man, and

somehow it sounded dramatic, it sounded mysterious. So that was the name I

chose.

BOGAEV: So you presented the Spider-Man idea to the publisher of then--Marvel

wasn't Marvel yet. It was Timely Comics.

Mr. LEE: That's right. In those days, it was called Timely. And I told them

I wanted to call the hero Spider-Man, and, oh, man, he was dead set against

that. He said, `Stan, people hate spiders. You can't--nobody's going to buy

a book called Spider-Man.' And then when I told him I wanted the hero to be a

teen-ager, he looked at me as if I was from another planet. He said, `Stan,

teen-agers can only be sidekicks. A hero can't be a teen-ager.' And finally,

when I told him that I wanted our teen-ager to have a lot of problems that the

average reader could empathize with, problems like he didn't make out so well

on dates, the girls didn't particularly like him, he wasn't even that popular

with the boys, he had to worry about earning a living, he didn't have enough

money, he had family troubles, that's when my publisher said, `Stan, don't you

know what a hero is? Those things don't happen to heroes.' So I really--I

was striking out on all counts.

BOGAEV: Now why do superheroes all wear these spandex costumes? The question

of the ages.

Mr. LEE: That is a very interesting question. Let me take you back in time a

bit. Remember I mentioned before Spider-Man, I had done a book called The

Fantastic Four? Well, that was the first of the so-called Marvel Universe

characters. And I wanted The Fantastic Four to be as different from other

books as Spider-Man was. So one of the things I decided was I would give none

of those characters costumes because I always felt if I suddenly developed a

superpower, I don't think the first thing I would do would be run to a costume

store and say, `Quick, give me a mask and some spandex.' So I just gave them

regular clothes, and I published the issue. And we started to get a

tremendous amount of fan mail, and most of the letters said something of this

nature: `Stan, we love the book. The Fantastic Four is great. Oh, man, are

we excited about it. But if you don't give them costumes, we'll never buy

another issue.'

Now I don't know the reason for that. I have wracked my brain. I have tried

to research it. I don't know why, but it just seems that the people who like

superheroes like to see the superheroes in costumes.

BOGAEV: Well, let's talk about the "Spider-Man" movie. There are a lot of

poses directly out of the comic strip in the movie that re-create Spider-Man,

for instance, hanging upside-down with his knees up. That's a classic

silhouette for Spider-Man.

Mr. LEE: Yeah.

BOGAEV: And also swinging through the streets of New York with his arms

straight, outstretched.

Mr. LEE: Steve Ditko, the artist, did such a wonderful job of those shots in

the beginning that he did of Spider-Man swinging and clinging to walls and

hanging upside-down. Most people who've read those early books still remember

those shots.

BOGAEV: Yeah. What do you think that the movie got right in terms of the

visual aesthetics?

Mr. LEE: Oh, I think the movie got virtually everything right. It got the

essence of Peter Parker, the shy young man who suddenly comes into his own

once he gets the superpower. It got his ambivalence, his feeling that somehow

this superpower he had gotten is as much a curse as a blessing. The only

thing--there was one little thing about the movie that I felt could have been

better. I never cared for the mask that the Green Goblin had. I think that

Willem Dafoe is such a fine actor, I would have loved to have seen his face

when he was the Green Goblin. I would have loved to have seen his

expressions. Somehow, the mask, which was solid and unchanging, to me wasn't

as dramatic as actually seeing his face would have been. But that is a small

complaint, and I thought everything else was absolutely wonderful.

BOGAEV: Now we have to get into the controversy that fans found troubling,

that Spider-Man's web powers in the movie were made organic. It was something

that grew from his genetically altered spider bite, as opposed to something

that, as you had written into the strip, something that he created as a

burgeoning young scientist.

Mr. LEE: Yeah. How about that? They dared tamper with my creation. Well,

let me tell you, if I had done the movie, I would have tried to keep it that

he created this little web shooter himself. I remember when Jim Cameron

thought that he would do the "Spider-Man" movie a few years ago, he did an

outline, a treatment for the movie, a very detailed one that was more than 50

pages. And he sent it to me, and it was a wonderful story. But I noticed

that he, too, made the web shooting organic. And I said to him, `Gee, why

don't you keep it the way it was in the book?' And he said, `Well, I think it

would be hard to make an audience believe that some kid could just create

something like that himself.' And then we talked about other things, and I

went home and I thought about it, and I thought the way I would have done it

would be in the beginning to show that Peter had always been--he was a science

scholarship student. I mean, that was a given. He was a very bright student

and he was winning a scholarship in science.

Now the one thing he was always trying to do--if he ever went for a doctorate,

this would be his doctorate thesis--he was trying to find something that could

be shot out of a tube and stick to walls and, you know, whatever. This web

was the thing he was trying to work on, but he never could get it right.

However, once he was stung by that radio--or bitten by that radioactive

spider, suddenly he knew how to do it. It not only increased his strength and

gave him spider power, but the bite and the radioactivity, whatever, made him

aware of how he could create that web shooter. Now that's the way I would

have done it.

But after I thought about it a lot and after I saw the movie, I'm inclined to

think that maybe Jim Cameron and Sam Raimi, who did such a wonderful job

directing the movie, maybe they were right. Maybe somehow it's more dramatic

to see him just do it the way he did, organically, and it also saved them a

lot of time because it would have taken quite a few extra minutes of screen

time to show it the way I had just mentioned. So I really have no problem

with it because when you do a motion picture, I think whatever makes the movie

good, well, that's the way you should do it. And it doesn't really contradict

the way I had done Spider-Man because the main thing is when I did it, he was

able to swing on webs. Well, in the movie, he's able to swing on webs. Where

the webs come from, that's really a minor difference. So it may upset the

fans, and I'm sorry it does, and I love them for their loyalty, but it really

doesn't upset me.

BOGAEV: Stan Lee is my guest. He is the former head writer, editorial and

art director, publisher and chairman of Marvel Comics. He was a leading

creative force behind Spider-Man, The Incredible Hulk, the X-Men and many

others. He now works in television and film. He is the executive producer of

the new "Spider-Man" movie.

And, Stan, we're going to take a short break, and then we'll talk some more.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

BOGAEV: Back with Stan Lee. He was the longtime head writer, editor and

publisher of Marvel Comics, where he originated many of Marvel's most

masterful masked men, such as The Incredible Hulk, The Fantastic Four, The

X-Men and Spider-Man. Stan Lee is chairman emeritus of Marvel Comics, and

he's also the executive producer of the new "Spider-Man" movie. And he has a

new memoir of his years in comics. It's called "Excelsior: The Amazing Life

of Stan Lee."

Now you grew up in New York during the Depression.

Mr. LEE: Mm-hmm.

BOGAEV: Did you read comics as a kid?

Mr. LEE: Yeah, but I read everything, and comics were included in the

everything. In those days, they had different kind of comics when I was a

kid. They were mostly reproductions or reprints of newspaper strips like Dick

Tracy and Barney Google and things that nobody would remember now. They

weren't the kind of comics they have today.

BOGAEV: And not superheroes, either.

Mr. LEE: No, not really. Well, they had, let's see, Flash Gordon. You might

call him a superhero.

BOGAEV: So how hard-hit was your family by the Depression? Did your dad have

trouble holding onto a job?

Mr. LEE: Oh, we were very hard--well, my dad was just not a lucky man when it

came to finance or to getting jobs. Unfortunately, most of my memories of

him, he was unemployed and he spent most of his time reading the want ads. He

had been a dress cutter, and I guess there were just no jobs for dress cutters

in those days. And I always felt tremendous pity for him because it must be a

terrible feeling to be a man and just not be bringing in the money that's

needed for your family.

BOGAEV: Did you feel that you had to rush through school to start work to

help out the family? I know a lot of Depression kids felt that.

Mr. LEE: Oh, absolutely. In fact, I worked while I was going to school. I

had a lot of part-time jobs, yeah.

BOGAEV: So how did you get your start in comics?

Mr. LEE: Accidently. I heard there was a job open in a publishing company

and I thought, `Well, maybe they publish books or magazines or'--I didn't know

that they published comics. I didn't know that that's where the job opening

was, in the comic book department of this little company. And I took the job

as an assistant. I did a little proofreading. I helped erase the pages once

they were inked. And I ran errands and did some copy reading. And after a

while they let me do a little writing, and then they let me do a little more

writing. And that was really how it started.

BOGAEV: And this was Timely.

Mr. LEE: Yeah, it was called Timely Comics at the time.

BOGAEV: So what kind of comics were they publishing then? And this

is--What?--the '40s.

Mr. LEE: Mm-hmm. Well, they did all kinds, but they were just starting. No,

actually I think it was the--they started in the middle or late '30s. They

were starting with some superheroes. They had The Human Torch, the

Submariner, Captain America and a lot of other heroes who have been forgotten

as the sands of time have obliterated them.

BOGAEV: I think you resurrected the Human Torch, though, right?

Mr. LEE: Yes, that and the Submariner and Captain America...

BOGAEV: Sure.

Mr. LEE: ...'cause I liked all three of those characters, so when I started

the Marvel line of comics for the company, I brought all three of them back.

BOGAEV: Now radio was really big. Were you a radio fan?

Mr. LEE: Oh, yeah. I loved radio. Obviously, they didn't have television

then. You know, one funny thing that I've always remembered about radio, and

I still get a kick out of it. Sunday night especially, that was--in our house

that was family night. And we'd eat delicatessen. We'd have hot dogs and

beans and some sauerkraut if things were good. And we'd sit around the radio

set and we would listen to Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, Jack Benny,

Eddie Cantor, Fred Allen. It was just wonderful. But the funny thing about

it was all the chairs were arranged--all the chairs--three or four of them,

they were arranged in a semicircle facing the radio. And we would sit and

watch the radio as if it was a television set, and almost everybody did that.

When you listened to the radio, you would seat yourself so you were facing the

radio. And it didn't seem strange to me then. When I think of it now, I

wonder, why did we do that?

BOGAEV: It's interesting, because the wonderful thing about your writing was

that it was so snappy. It seemed to speak to me of radio. And you loved

lots of slogans and alliteration, the Green Goblin...

Mr. LEE: Oh, yeah.

BOGAEV: ...and Doc Auch(ph), and Dr. Doom. And I remember some

incantation--What was it Dr. Doom used to say? `By the hoary hosts of...'

Mr. LEE: No, that was Dr. Strange.

BOGAEV: Oh, I get the doctors confused.

Mr. LEE: We had a number of doctors. Dr. Strange was a magician. I called

him the master of the mystic arts.

BOGAEV: That's right.

Mr. LEE: And obviously, he would cast spells and he would do magical things.

Well, I couldn't have him say `abracadabra' when he wanted to do something. I

felt I had to create little expressions for him, little incantations that he

could utter. So I'd have him say things like, `By the hoary hosts of

Hogith(ph), let though-and-such happen,' or, `By the crimson rings of

Sitirak(ph),' or--I just made up any silly thing that sounded the way I

thought it should sound. Funny thing about it was in later years I did a lot

of college lecturing. And very often people in the audience, during the

questions and answer period, would say, `Stan, we've been making a study of

the incantations of Dr. Strange, and my friends and I have come to the

conclusion that you were very heavily influenced by the ancient Druid

writings, or by'--and, you know, they would mention something very obscure

that I had never heard of. But it's funny how people will always read more

into what you write than you ever put in there.

BOGAEV: So you don't think you drew on your early reading or listening to the

radio or any of those...

Mr. LEE: Oh, sure.

BOGAEV: ...like pop culture pastimes?

Mr. LEE: Oh, sure I did, but only in a very superficial--what I mean is, I

didn't use expressions I remembered reading. I used expressions because I

remembered I used to like expressions. But I have no memory at all--I never

could remember a spec--the only thing I remember, when you were talking about

radio, there was a radio program I listened to--I must have been about eight

or 10 years old--I don't know--and I don't remember what the program was, but

the introduction, the announcement of it, I felt was the most dramatic thing

and it always stayed in my mind. The name of the show was "Chandu, the

Magician," C-H-A-N-D-U. And the way the announcer said it, there was a big

gong that would be--I guess you hit a gong the way--if you remember the old

J. Arthur Rank movies, when they would hit a gong when you saw the name on

the screen. Well, the announcer would say, `And now Chandu!' and at that

point, it would go `bong,' `the magician.' So him saying, `And now Chandu,'

and then that bong and then the words `the magician,' I tell you, to me that

was the most dramatic thing I had ever heard. So you could see I was corny

even as a kid.

BOGAEV: Stan Lee of Marvel Comics. He's an executive producer of the new

"Spider-Man" movie. He also has a new memoir, "Excelsior: The Amazing Life

of Stan Lee." We'll continue our conversation in the second half of the show.

I'm Barbara Bogaev, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite from vintage "Spider-Man" cartoon)

Unidentified Group: (Singing) Spider-Man, Spider-Man, does whatever a spider

can. Spins a web any size, catches thieves just like flies. Look out, here

comes the Spider-Man. Is he strong? Listen, bud, he's got radioactive blood.

(Announcements)

BOGAEV: Coming up, Maureen Corrigan reviews the new suspense novel "The

Emperor of Ocean Park," and we continue our conversation with the man who

co-created Spider-Man and helped usher in the golden age of Marvel Comics,

Stan Lee. He has a new book about his life and he's executive...

BOGAEV: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Barbara Bogaev.

Let's continue our interview with Stan Lee of Marvel Comics. Along with a

team of artists, which included Jack Herbie(ph) and Steve Ditko, Lee created

the hit series Spider-Man, The Incredible Hulk, X-Men, The Fantastic Four and

many others. He served as head writer, art and editorial director and

publisher of Marvel. He's now chairman emeritus. And at the age of 80, he's

working in television and film. He's an executive producer of the new

"Spider-Man" movie. He also has a new memoir of his long career in comics.

It's called "Excelsior: The Amazing Life of Stan Lee." Lee got his start in

comics in the 1940s in New York. In 1942, he enlisted in World War II.

During the war, what was your--you enlisted. What was your wartime

assignment?

Mr. LEE: Well, it was very funny. I started out in the Signal Corps and I

trained to go overseas and do wire repairing and I would be the one who went

ahead of the troops and make sure that they had their communications set up.

But just before I was going to go overseas, somebody found out that I had done

comic book writing and I was transferred to the Army--to the Signal Corps--I

don't even know what the unit was called anymore, but it was stationed in

Astoria, New York, and they did training films and they wrote instructional

manuals. And I was one of the people who wrote the training films and the

instructional manuals. And I was with people like William Saroyan and--I

mean, some of the biggest names in Hollywood, and I was the token nobody

there. I guess they needed one guy that nobody'd heard of to show they were

democratic. And that's what I spent most of the war doing. I was writing

films and training manuals.

BOGAEV: Now after the war, people were really starting to get pretty serious.

They wanted to get back to their lives and certainly they were just relieved

and looking for entertainment. What kind of comics sold well in that post-war

environment?

Mr. LEE: Post-war environment was amazing. Everything sold but what happened

was the books--they worked in trends. All of a sudden, everybody would be

doing Western magazines and they'd be selling like there was no tomorrow.

Then one day, the sales would slump. So the publishers would start doing

crime--you know, cops and robbers stories and those would sell for six months,

eight months, a year. And then those sales would slump. And they'd start

doing romance stories, and then when the public got tired of those, there'd be

war stories. It was one trend after another. And no trend lasted much longer

than a year or so. And it's very strange because only when the superheroes

started, and I really think it's when Marvel started with its group of

superheroes, it's as though there were no more trends. Since the early 1960s,

superheroes have been the best-selling comic books ever until today.

BOGAEV: Now after the war, you were back at Timely. Hadn't turned to Marvel

yet. And you were there in New York and--did all of these trends--did you

just jump on them all in a row...

Mr. LEE: Every one of them.

BOGAEV: ...whatever DC did or whatever any other comic company would do,

you'd hop on?

Mr. LEE: Yeah. That was pretty much my publisher's formula. He would see

what was selling and then we would flood the market with books in the same

genre. And I can't complain. It worked. I mean, he did very well doing

that. We weren't that original. I created a few new things but none of

them--I realized later you can't sell something new unless it's promoted, and

we did not know or did not care to promote things.

BOGAEV: Now could we talk about the '50s? Because it was an interesting

progression, the red-baiting scare, McCarthyism, first it hit Hollywood and

there were congressional hearings into Hollywood, and then comic books came

under attack, too. There was a congressional hearing also which investigated

links between comics and violent crime and juvenile delinquency, and I think a

New York psychiatrist, Dr. Fredric Wertham, led a kind of comic book

witch-hunt. What are your memories of this Dr. Wertham's most outlandish

arguments? It almost sounds like a comic book.

Mr. LEE: Well, I was very unhappy about Dr. Wertham because I had read a

book he had written--I may have mentioned, I was a voracious reader when I was

young. He had written a book--I think it was called Dark Legend, about a boy

who had murdered his mother, and it was a case history that apparently Wertham

had been involved in. I read it when I was about 13 or 14 years old and

thought it was one of the best-written, most absorbing books I had ever read.

And I figured this Wertham must be a great guy. And then years later, to have

him be the one who attributed every ill that flesh is err to, to comic books,

and to be this ranting, raging, rampaging fanatic against comics--I was very

disappointed in him. But he literally started a crusade against comics. And

in those days, crusades caught on. Anything that any doctor or person who was

a psychiatrist or had any title in front of his name said, people would be

influenced by, and he really caused a lot of trouble. A lot of comic book

publishers went out of business because of his diatribes and tirades. The

company...

BOGAEV: Well, what were some of his arguments? I think there was something

about Robin of Batman and Robin...

Mr. LEE: Oh, yeah, he...

BOGAEV: ...he was tremendously offended by the legs, Robin's bare or--legs in

tights.

Mr. LEE: He would say ridiculous things like the fact that Batman had this

young sidekick Robin, he'd say, `The readers know what the real relationship

is between Batman and Robin and Robin's legs being exposed the way they were.'

I mean, the things he said were so insane, and it's almost embarrassing to

mention them. But he did get the ear of Congress and a company like DC

Comics, which now publishes Mad, they had a lot of books called The Crypt of

Horror(ph) and the Vault of Terror and things like that. He totally put them

out of business. Luckily, they came out with Mad which was better than any of

them, and they've succeeded, but if not for Mad, they would have gone bust.

He was a very dangerous person because he could see evil in anything that was

written or drawn. And unfortunately, for a while, a lot of people listened to

him.

BOGAEV: Were you fed up by all this? I mean, was this a point in your career

where you thought `Maybe I should just get out of this business. This is

ridiculous'?

Mr. LEE: Yeah. I wanted to get out. Not because of Dr. Wertham, because

that was just insanity. That didn't bother me. But what happened was I

realized by early 1960 that I had been in this business for about 20 years and

I was still writing pap. I was writing things for young kids. My publisher

had said, `Don't use words of more than two syllables. Don't worry about too

much dialogue. Don't worry about characters. They shouldn't--just tell the

simplest stories possible.' As you can imagine, I felt what I'm doing is

worthless. I'm not getting anywhere. So I was about to quit and then my wife

said to me `You know, Stan, if you're going to quit anyway, before you do, why

don't you do one book the way you'd like to do it? The worst that can happen

is he'll fire you. And you want to quit.' So that's when I did the book

The Fantastic Four. And I tried to make them more believable characters and

to give them different personalties and I paid attention to the dialogue and

so forth. And from then on, everything was great because the book sold and I

tried to do all the other books I did in the same style, so then I was happy

and I stayed with the company.

BOGAEV: Well, The Fantastic Four really pretty much marked the rise of Marvel

Comics. That was a real turning point for the company. And what people most

remember about The Fantastic Four I think is that they were so dysfunctional.

It was kind of like a bickering, dysfunctional superhero family.

Mr. LEE: Well, you're absolutely right. And again, I think that's one of the

reasons that they were popular, because just like Spider-Man's Peter Parker

being the kind of teen-ager that the readers could identify with, I think for

the first time, The Fantastic Four was a group that readers could identify

with. They were not dissimilar to their own families. And see, I didn't have

a girl, for example, who had no idea that the hero was really a--that the man

she loved was really a superhero. She knew who he was. In fact, she was

engaged to him and she was part of the team, and there was a...

BOGAEV: This is Sue Storm, you're talking about...

Mr. LEE: Sue Storm, the...

BOGAEV: ...one of The Fantastic Four.

Mr. LEE: That's right.

BOGAEV: She was Mr. Fantastic's girlfriend, The Invisible Girl.

Mr. LEE: Exactly. Mr. Fantastic, as he modestly called himself. It was

his girlfriend. And then...

BOGAEV: I mean, it really was a soap opera, right?

Mr. LEE: It was. It was. But you see, to me, every story should be done

like a soap opera because that's what people like. If you don't have the

characters' personal problems, if you don't have people who are having

difficulty relating to other people, if you don't have characters with

problems that seem unsolvable and you wonder, `How will they ever get out of

this?' then what have you got? You've just got a series of incidents and you

don't care about those, because if you don't care about the characters, you

can't care about the story. At least that's the theory I've always used.

BOGAEV: Stan Lee's new memoir about his career with Marvel Comics is called

"Excelsior: The Amazing Life of Stan Lee." We'll continue after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

BOGAEV: I'm talking with Stan Lee. He was the longtime editor, art director

and publisher and later chairman of Marvel Comics. He now works in television

and film, and he's the executive producer of the new "Spider-Man" movie. He

also has a memoir out about his time in comics. It's called "Excelsior: The

Amazing Life of Stan Lee."

Now The Fantastic Four was a big hit, and somewhere in this stretch of the

'60s, you put out a series called Sergeant Fury and His Howling Commandos.

Mr. LEE: Yeah.

BOGAEV: Very different from The Fantastic Four, and I believe that that

series started because of a bet? What was that all about?

Mr. LEE: Well, what happened was we had been doing very well. The Fantastic

Four was a hit, The Hulk was a hit, The X-Men were a hit, Spider-Man was a

hit. We then did Ironman, Dr. Strange, Daredevil--I'm probably forgetting a

few others--and they were all doing well. I mean, we now had what we called

the Marvel Universe, and we had become the biggest and most successful comic

book publishers. So one day, again, I was talking to my publisher, who's a

great guy, but we often didn't agree on things, and he said, `Stan, what is it

that's making these books sell so well?' You know, immodestly, I wanted to

say, `It's because I'm writing most of them,' but I didn't. But he said, `I

think it's the titles. I think they are great titles.' I said, `That has

nothing to do with it.' So then I said, `Look, let me prove to you the titles

have nothing to do with it.'

Suppose--oh, no, what it was, I said, `It's the style of the writing,' and I

mentioned what we just said. Even though they're superhero stories, I'm

trying to treat them like soap operas, where the characters' personal lives

are important. He didn't see it that--he said, `No, I don't think that's it.

I think it's the titles.' So I said, `OK. You know what I'm going to show

you, what I'm going to do for you? I'll make you a bet. I'm going to put out

a book with the worst title I can think of, and I'm going to put it out in a

field, in a genre that nobody is interested in,' and at that time, nobody

wanted war stories. I mean, people were sick of them, they were sick of war.

I said, `I'm going to do a war book,' and I thought and I thought, and I came

up with the title Sergeant Fury and His Howling Commandos, which is much too

long a title and nobody...

BOGAEV: Well, it doesn't alliterate.

Mr. LEE: That's right, it wasn't...

BOGAEV: That's another problem.

Mr. LEE: ...alliterative, and nobody knew what a howling commando was. So I

said, `If I can make that sell, would you believe that--and the fact that it's

a war book, there's no reason for it to sell, but if it does sell, it's going

to be because of the style in which it's done.' So we did it and luckily,

sure enough, it sold, and he grudgingly admitted maybe I had a point there.

That we couldn't kill the book--personally, I hate war stories, so after--I

don't know--a year, two years, whatever it was, I dropped the book and we got

so much mail from readers, we had to continue it. I didn't want to do new

stories. I just reprinted the ones we did. Those sold just as well as the

original ones. In fact, we kept it going for years. And the character was so

popular that today, we have him as a colonel, he's no longer a sergeant, we

have him in the present a colonel, the head of a group called Shield.

But I've got to mention one other thing. It was also a book that had the

first ethnic group of heroes. In Sergeant Fury's platoon, we had a Jewish

soldier named Izzy Cohen, we had a black soldier, an Italian soldier, a

Scandinavian soldier. We even had a gay soldier. And this was in the middle

1960s, and I think it took a little courage to do it then, and everybody said

to me, `Oh, the book won't sell in the South, it won't sell in the East, it

won't sell in the West.' It sold all over, proving that people are really

more broad-minded and smarter than anybody gives them credit for.

BOGAEV: So tell me about this gay character. What was the story with him?

Mr. LEE: The gay character? Oh, well, he was just one of the members of the

platoon. His name was Percy Pinkerton. He was English, and his weapon--he

carried an umbrella. I mean, he also carried a gun, but he would use the

umbrella also to confuse people. And, I mean, I didn't play up the gay part,

but somehow you could assume he was gay in reading the stories. But he was

brave and nice and friendly and everybody liked him, and he was one of the

platoon, one of the guys.

BOGAEV: A lot of kids who grew up in the Depression felt very insecure

financially and chose very stable careers. Did you ever feel that this just

is not the career for a grown-up and just not stable and financially secure

enough for you?

Mr. LEE: Well, I think for the first 20 years, I felt this is definitely not

the career for a grown-up, and very, very often I wanted to leave, to quit,

but I would get a raise or I'd work with a new artist and get interested in

what we were doing or something would happen to make me decide to stay a

little longer. But my biggest regret was during those early years, nobody had

any respect for what I was doing. Nobody cared about a fellow who wrote comic

books. I would be at a party and somebody would come over and say, `Hey, what

do you do?' and I knew what was coming, so I tried not to tell. I'd say, `Oh,

I'm a writer,' and I'd start to walk away, but the person would follow me,

`Really? What do you write?' `Oh, stories for young people,' and I'd walk

away further, but finally, `What kind of stories?' At some point, I had to

say comic books, and at that point, the person would turn away as if I had the

plague. I mean, it just was the bottom of the cultural totem pole.

Now it's changed now. Now every movie producer is looking for a new comic

book to make a big-budget movie out of, and it's a whole different world. But

in those days--another bad thing about it, I thought `Even if I quit, what

would I do?' I couldn't go to Time magazine and say, `Hey, I'd like to work

for you now. I used to do comic books.' You know, nobody would be impressed.

I felt I had wasted so many years because it wasn't leading to anything, and

that was another reason that I kind of just stayed there.

BOGAEV: Did it make you nervous, though, and maybe accounts for the real

drive that you seem to have had? I mean, you had a huge creative drive.

Mr. LEE: Yeah. Well, you know what really made me that way perhaps? It was

my father. I used to just wish that that poor man could find a job, and I was

stupid. That's why I'm not a businessman. Instead of me wanting to maybe

create comics for myself and form my own company, which I could have done, all

I wanted was a steady job. To me, it seemed as if having a good job, a steady

job is the greatest success a person could attain, only because my father

never had one. And I think that's another reason that kept me at Marvel, or

at what was then Timely so long, because I felt at least I've got a job,

you know, and I really should have left and tried to start a little something

of my own, but, well, I didn't know.

BOGAEV: Stan Lee, I want to thank you so much for talking with me today.

Mr. LEE: That's it? I'm just getting started.

BOGAEV: Stan Lee is an executive producer of the new "Spider-Man" movie. He

talks about his long career with Marvel Comics on a new DVD made with

filmmaker Kevin Smith called "Stan Lee's Mutants, Monsters and Marvels."

Coming up, a review of the new suspense novel by Law Professor Stephen L.

Carter. This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Positive review of the new book "The Emperor of Ocean

Park" by Stephen L. Carter

BARBARA BOGAEV, host:

It almost seems a requirement these days that thriller writers attend law

school first and then begin their successful literary careers. Think of John

Grisham, Lisa Scottoline, Brad Meltzer and Scott Turow. Aside from Oliver

Wendell Holmes, it's much more unusual for a well-established legal scholar to

attempt to write imaginative literature. Now Yale Law School Professor

Stephen L. Carter has broken that precedent with his new suspense novel "The

Emperor of Ocean Park." Book critic Maureen Corrigan says it's a no-fault

case of terrific storytelling.

MAUREEN CORRIGAN reporting:

For the past 20 years, Stephen L. Carter has been a professor of law at Yale

University. He's also become prominent in the world beyond the academy

because he's an African-American scholar who argues passionately against

affirmative action. In addition, Carter has written seven polemical books for

a wide readership on subjects like civility and the conflict between secular

law and religious belief. But man, has this guy ever been wasting his time.

All these years Carter has spent intellectually noodling around, he could have

devoted to what clearly now turns out to be his true calling, writing

brilliant suspense fiction. The evidence: a page-turner of roughly 600 pages

called "The Emperor of Ocean Park," which is surely going to be the smarty

set's must-read vacation book this summer. I say smarty set because, along

with murders, missing manuscripts, double agents, tricksters and plot twists

aplenty, Carter also tosses in sharp, droll insights here on identity

politics, grade inflation, affirmative action, the decline of morals and,

infecting every page, America's chronic case of racial sickness.

Like other first-rate thriller writers--Graham Greene, John Le Carre, Ken

Follett on a good day, Don DeLillo when he's in a certain mood--Carter

gleefully realizes that the suspense genre is social commentary that packs a

pistol. In "The Emperor of Ocean Park," Carter leads his readers into worlds

within worlds, the upper echelons of academia, the law, the federal government

and, foremost, the neighborhoods and social haunts of the black bourgeoisie.

Carter escorts us into the elegant urban mansions along Washington, DC's Gold

Coast that are owned by wealthy African-American professionals. He also takes

us out to the historically black resort town of Oak Bluffs on Martha's

Vineyard.

Through his beleaguered hero, Talcott--nicknamed Tal--Garland, who, like his

creator, is an African-American law professor, Carter probes deep into the

necessarily paranoid double consciousness of a successful black man in

America. Tal is a guy who recognizes from hard experience that no matter how

many academic degrees he attains or how many crimes he solves, he'll never

clear himself of the suspicions his skin color automatically generates among

so many white Americans.

The baroque plot of "The Emperor of Ocean Park" is so ingeniously and

frantically constructed that it defeats summary, but here's a shallow attempt.

Tal's father, the eminent Judge Oliver Garland, dies or is murdered in his

Gold Coast house one evening. The judge was a cryptic, embittered man given

to referring to his fellow African Americans as `the darker nation.' At one

time nominated by Reagan for the Supreme Court, the judge was defeated and

publicly humiliated by his questionable friendship with a major criminal.

Upon the judge's death, Tal is besieged by a crowd of weird characters who

insist that he knows the secret location of the judge's arrangements, whatever

they are. Slowly, Tal is drawn into the mystery of hunting for this

maguffin(ph), this Rosebud, eventually catching on that the obsession with

chess he shared with his father may be essential to decoding the clues that

are coming to him via the mail and the morgue,

Meanwhile, Tal's promiscuous wife, a preppy black attorney nicknamed

Kimmer, has been nominated for a federal judgeship and she warns Tal that

if he doesn't stop his embarrassing investigations, the marriage is kaput.

Like many another suspense hero, however, Tal is caught between the proverbial

rock and a hard place, because he's also been anonymously threatened that if

he does stop hunting for the arrangements, his wife and his beloved

three-year-old son will be subject to a grisly fate.

Carter's humor, his gift for drawing out the Gothic atmosphere in the vast

shadowy houses and Ivy League buildings Tal inhabits, his unapologetic delight

in melodramatic literary trappings like moonlit cemeteries and his unflagging

ingeniousness make "The Emperor of Ocean Park" a first-rate suspense tale.

But above all, it's Tal's upright sensibility and his depressive, smart voice

that lingers. Listen to him here talking about the contemporary state of

legal education. `Nowadays I earn my bread by writing learned articles too

arcane to have any influence and trying to stuff some torts or administrative

law into the heads of students too intelligent to content themselves with B's,

but too self-absorbed to waste their precious energy on the tedious details

one must master to learn A's. Most of our students crave only the credential

we award, not the knowledge we offer. And as generation after generation,

each more than the last, views us as merely a vocational school, the

connection between the desire for the degree and the desire to understand the

law grows more and more attenuated.'

Tal is the kind of straight-arrow, Jimmy Stewart type scrapper you would want

to have beside you when the bullets are flying, as well as in front of you in

the classroom, educating you about the law in the books and the law of the

streets.

BOGAEV: Maureen Corrigan teaches literature at Georgetown University.

(Credits)

BOGAEV: For Terry Gross, I'm Barbara Bogaev.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.