Contributor

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on September 23, 2014

Transcript

September 23, 2014

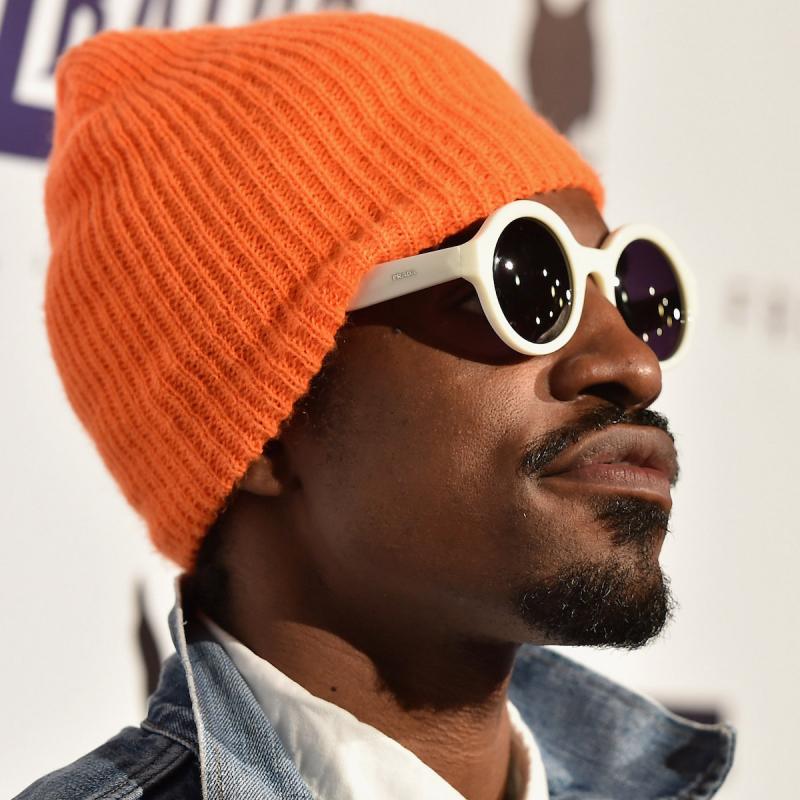

Guest: Andre Benjamin & John Ridley

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

(SOUNDBITE OF JIMI HENDRIX SONG, "PURPLE HAZE")

GROSS: A new biopic focuses on one year in the life of Jimi Hendrix between 1966 to '67. When he moved to London, where he developed his own sound and transformed himself from Jimmy James - a guitarist working as a side man in R&B bands - into the electrifying performer known as Jimi Hendrix. It was the year he formed his band - the Jimi Hendrix Experience - and recorded his first album "Are You Experienced," which led off with this famous track.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "PURPLE HAZE")

JIMI HENDRIX: (Singing) Purple haze all in my brain. Lately things just don't seem the same. Acting funny, but I don't know why. Excuse me while I kiss the sky.

GROSS: In 1970, soon after Hendrix became a star he died of complications related to a drug overdose. He was 27. The new film is called "Jimi: All Is By My Side." My guests are the films' writer and director John Ridley and its star Andre Benjamin. Ridley won an Oscar for his screenplay for "12 Years a Slave." Andre Benjamin - who also performs under the name Andre 3,000 - co-founded the hip-hop group Outkast - which had the 2003 hit "Hey Ya!" He's also acted in the films "Be Cool," "Idlewild" and "Four Brothers." Andre Benjamin does his own singing in the film but we don't get to hear any songs written by Hendrix, because Ridley wasn't able to get the rights to those songs. Let's start with a scene from early in the film - before Hendrix goes to London. Linda Keith - who was a girlfriend of Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones - sees Hendrix perform in New York and realizes how much unrecognized potential he has. She becomes his champion, using all her connections to try to get him a break. After striking out she brings Chas Chandler - the bass player with the Animals - to see Hendrix perform. Chandler is blown away. He's planning to stop performing and become a manager and he wants to manage Jimi.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "JIMI: ALL IS BY MY SIDE")

ANDRE BENJAMIN: (As Jimi Hendrix) Are you okay?

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: (As character) I'm off the tour in three months. I think it'd be a hell of a thing if you came over to London.

BENJAMIN: (As Jimi Hendrix) London? Man, there's so many great cats over there already playing though.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: (As character) But they haven't got you. That's for damn sure. There will be no stick in the - about this cord or that. They'll be mad for what you're doing over there. Everybody there - everybody's doing well- they're all working off the blues structure...

BENJAMIN: (As Jimi Hendrix) No, you see I don't want to get caught up in those kind of labels though, you know. I don't want it to be, well okay, well he's playing the blues, or he's playing like R&B, or Soul or what - all that kind of stuff - those cages, man. I just....

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: (As character) I'm not saying you have to play...

BENJAMIN: (As Jimi Hendrix) You know, it's not about style, you know, it's - I want my music to go inside the soul of a person. You know, it's - for me its colors. I want people to feel the same way I see it. You know, it's just colors - that's it. And the rest is just painted with a little science fiction here and there. I don't want to freak you out- this early.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: (As character) I've got to get you over to London.

GROSS: (Laughter) That's a clip from "Jimi: All Is By My Side." John Ridley, Andre Benjamin welcome to FRESH AIR. Congratulations on the film. Let me start by asking what Jimi Hendrix means to each of you. And John, since you wrote and directed the film, do you want to start that off?

JOHN RIDLEY: To me Jimi is a consummate artist. He wasn't so much about going out and trying to please a crowd - but trying to create something that brought people to his vision for music, his vision for life and the way he expressed things. One of the things that was very interesting to me, in particular, as I found out more about him as a player. He never particularly liked to play the same thing the same way. You know, there's an expectation from an audience to do this thing that you're known for. And I think it's really a remarkable individual who appreciates the people who like his music or whatever they create, but at the same time feels like - I need to give you what's inside of me, not just what you think you want.

GROSS: Andre Benjamin when - the film is set in 66, 67 - you're not even born yet, you're about seven or eight years away from being born. So how did you discover Hendrix and what did he mean to you?

BENJAMIN: I discovered Hendrix later on in life. Maybe in my early twenties and it was in a film clip. I'm not sure if it was "Apocalypse Now," or "Full Metal Jacket," or "Platoon" - I can't remember. But it was a helicopter scene and "All Along the Watchtower" was playing and , you know, these guitar solos just kind of hit me and it was like -who? What kind of music is this? Who is this? And from there I still didn't really know what Hendrix was about, I think most black kids that , you know , coming up in the hip-hop era , you know , you just see Hendrix as this wild character. And you're not really so much into the music - I didn't get into the music later on in life once I picked up a guitar - and you know , just really realized how great he was on the instrument. So those were my first Hendrix times.

GROSS: John Ridley - why did you want to focus on this one year in Hendrix's life? You know, most biopic's are like the whole life or a few years. It's just a really significant , really interesting and rich period. But it's , you know, a small piece of his life. Why did you choose this year - the year that he's in England before returning back to the states and performing at the Monterey Pop Festival?

RIDLEY: Years ago, late night when I was writing I was on the Internet, listening to some Hendrix rarities and there was one song in particular that was playing. And it was - even for Hendrix - it was just a very powerful, moving, deep and emotive piece of music. And one that I had never heard before. And I looked at the title and it was called "Sending My Love to Linda." And I started going - well, who's Linda? And even for someone who'd grown up reading so many Hendrix stories, there were all these bits and pieces of this particular era and this particular year that were sort of scattered in various places and not really connected. And the more I read and the more I really tried to put these various stories together , the more exciting that year became to me. Not just because it was transformative for Jimi himself, but the connectivity of these individuals - their chemistry, their character, their nature and how informative they were in helping create the Jimi that we all have come to know or, even more importantly, that we think we know.

GROSS: So why did you think of Andre Benjamin as the person to play Hendrix. It's a great choice. I think it's a terrific performance.

BENJAMIN: Thank you.

RIDLEY: You know, Andre originally for me - one of my agents said , look if you really want to do this film you've got to find someone who can carry it. And I thought about a few people - I landed on Andre. Obviously he has a bit of a physical resemblance to Hendrix and certainly has a deep musical background - but it was really after I had the opportunity to sit down with Andre, even for a few moments, and his nature, his curiosity, the respect he has for music in general and certainly the subject matter in particular. Just his anthropological approach to music and the depth of knowledge that he has about the subject matter. It really made me believe that this was an individual who's going to bring a really honorific approach to this person. And beyond that, Andre was an individual who was really willing to put in the work. If you're going to tackle subject matter like this it takes an amazing amount of work. And Andre, to his credit, I calculate the time - it was about seven and a half or eight months - that we worked on all aspects of this film. And that's pretty amazing.

GROSS: Andre Benjamin - in the film you give him a very laid-back, whatever happens, kind of approach to speaking. He's kind of withdrawn - not very talkative as we see him in the film. Can you talk a little bit about getting his speaking voice - and his style of speaking?

BENJAMIN: Well, Jimi Hendrix was from the Northwest so, you know, just in that location you already start with just a speaking palette that's completely different from where I'm from, I'm from the opposite town - I mean the opposite side of the United States. So my southern drawl was really thick, so that was - I really think the left-handed guitar playing and the voice was probably the hardest part, well the most challenging part of doing this film. I work with a vocal coach, listen to a lot of interviews and kind of just in my headphones - just repeatedly - and, you know, it starts with the mimic. And, you know, there were certain vocal exercises that I learned from my vocal coach even at one point in time I was walking around with a wine cork in my mouth and speaking with the wine cork because Jimi, he protruded his mouth forward and he talked with a lisp, kind of .So I had to try to mimic that kind of thing. A funny thing is, I tried to find like a , I guess a meeting point to something that I was familiar with in Hendrix, and there's a cartoon character called Snagglepuss. When I was a kid there was this cat that he would say, stage left even. And to me it was Hendrix-y and so every time we would get ready the set, you know, you would hear the stage left even. You know, that was kind of my thing to get into, you know, the Hendrix voice. Because he was real sing-songy and getting out the slang too, the slang was really important. So I could speak like I'm from the sixties. You know words like dig - dig was really important - that was a Hendrix word. It's kind of like saying - see what I'm saying, see what I'm saying - how people say that now. So when people make movies, you know, about people from now ,you'll have actually actors studying dude - you will. It's just part of the speech so. Yeah, that was the fun part.

GROSS: Can you tell us about one of the other vocal exercises you did to find Hendrix's voice?

BENJAMIN: Yes. Because everybody speaks in a different way depending on how you were raised. If you were a timid person you may put your voice in your nasal cavity - kind of strained. Some people are really confident and so some people speak from the chest. Hendrix spoke in like a cavity - he had almost like a cave in the back of his mouth. So it made, you know, it made everything, you know, kind of bigger. And I learned those exercises, I learned how to pull the back of my tongue down to make it - to make a cavity , basically, to make a cave so my voice came out a little bit differently. I'm a little bit more nasally, you know, maybe because I was raised- I'm from the south and, you know, we always have this kind of thing from the South where we kind of feel like, you know, people look at us as country bumpkins or whatever. So I think we're little bit more strained when we come around people. Learning how to make that cavity was really important.

GROSS: Did that include getting a kind of yawn effect in the back of your throat?

BENJAMIN: Yes. That's the effect that I'm talking about. And also Hendrix he stuttered a bit when he got excited. And so his speech was kind of broken. It was, you know, it wasn't - it was fluid but then it broke at certain times so I had to practice kind of the start-stop, start-stop, you know, in and out kind of thing.

GROSS: And the hair and the closing - since you are so into style, you have such a great sense of style. Did you want a hand in choosing what you'd wear as Hendrix?

BENJAMIN: No not at all. I'm not - I don't consider myself a true actor in that way. But when I get the opportunity to do a film I leave it to the wardrobe people because people know me as you know this person that's in the style I never want myself to bleed too much into the character. So I leave it, you know, I just leave it be and they did an excellent job. Like I watched them from scratch, you know, research the Hendrix - even down to patterns. You know, they would zoom in on patterns and re-create the patterns. So they were excellent. And wardrobe and hair, you know I had always had hair up until after the Hendrix movie. So, you know, I just never permed my hair so when I did for the Hendrix movie we actually used old-school perm and I would put rollers in my hair in the same way that Hendrix would do every night. You know, every night, you know, Hendrix would roll his hair.

GROSS: I know, I've seen to biopic lately with guys with roller in their hair - James Brown (Laughter) and Hendrix. That's really funny.

BENJAMIN: That was the style back then.

GROSS: I have two guests - John Ridley wrote and directed the new film "Jimi: All Is By My Side." And Andre Benjamin who stars as Jimi Hendrix. We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(MUSIC)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, we're talking about the new movie "Jimi: All Is By My Side," which is a new movie about Jimi Hendrix, with my guests Andre Benjamin, as Jimi Hendrix, and John Ridley, who is also with us, wrote and directed the film. And he also wrote "12 Years A Slave." So John Ridley, you had to make the decision to go with Andre Benjamin's singing, which I think was a really good choice because it's so natural and because he does such a great job of it. Did you ever think well, maybe you'll use the records, or was that not even an issue because of the estate, like they wouldn't have allowed it? Yeah.

RIDLEY: It was complicated in many ways. But again, I think to a degree, when you get on stage and you give performances and you end up lip-synching, you know, that was one of my other concerns just in terms of the visuals is when you look at the film and you see an artist and it's just off by a millimeter - just by a hair - it just adds a sense of being false. And that's very different, as Andre was saying, from going into a studio, playing it live, giving that live performance energy and making it your own. So it's one of those things - I mean, I've seen in different kinds of films where people have had the artifacts or the intellectual property and they choose to synch it and, you know, it ends up being a little music video-ish, as opposed to doing it in a manner where there's a little bit more ownership. So even in that regard, I think we would've - I would've chosen to do some kind of an original version where we had more ownership, not just of the material itself, but how it would look on film.

GROSS: After you learned to speak and sing in Hendrix's voice - but particularly after you learn to sing like him and you learned all these things about your throat and your voice and placement and everything so you could get it to sound like Hendrix's, did it affect your own singing? I mean, when you learned that your voice could do things that you maybe didn't know it could do before.

BENJAMIN: Anybody that takes vocal lessons, they'll know that if you pull the back of your tongue down and relax it, you actually can hit higher notes. It's not a strain. It's actually easier on your voice, so in that way I did learn, I guess, a few cues. And one thing - I have to say one of the best things that John made sure I did on set, he wanted me to speak in Hendrix's voice as much as I could, even when we had, like, off days and we were kind of just meeting. He wanted to hear it, so it wasn't just like I would jump on set and then, you know, you yell action then I'd have to go right into it. So in that way it kind of kept it at, like, on a natural level so it didn't feel like - it didn't feel phony. I honestly think if I would've jumped on set and just had to go at it right then and there, it would feel phony and it would take me a minute to get into it. And I also feel like if I wore a wig, I think I would feel stupid doing a Hendrix voice.

RIDLEY: Yeah, we were not going to do wigs. We wanted to have everything be as natural as possible. And early on I felt bad - Andre, we'd moved out to - actually well, we were still here in LA and then we went out to Dublin - and we'd sit down or have coffee or watch a film or something and start talking to me and he'd be in the middle of a thought and I'd go Andre, I'm sorry. I'm sorry. I don't hear Hendrix.

BENJAMIN: Yeah.

RIDLEY: I don't hear Hendrix. First, he looked at me like come on, man. And then, after a while, I'd just kind of give him a look and he'd be like OK, OK, OK, I got it.

GROSS: So Andre, did this mean that you would say to John Ridley, dig John (laughter)?

BENJAMIN: Yeah, yeah. I mean, I would go into Hendrix's voice just normally speaking, like, about anything. Yeah, you just go into it and that's just to keep it natural. And just that time...

GROSS: So you had to speak in '60s slang when you were on the set (laughter)?

BENJAMIN: Yes. Yes. But that time was so important for this film. You know, I've always read stories about, you know, when "The Godfather," you know, they would, you know, have dinners and that kind of thing, you know, before they shot just to get to know each other. You know, with Hayley and Imogen, you know, it's kind of like, you know, my leading ladies in the movie, we actually went on dates and spent - well, I call them dates. You know, we went, you know, we went out on the town. You know, we had like, what, two, three weeks to prepare?

RIDLEY: Yeah.

BENJAMIN: So once we got to Ireland, you know, we would just go out as much as possible and, you know, I got time to spend with these two great women and it was...

GROSS: In Hendrix character? Did you...

BENJAMIN: It was excellent.

GROSS: Did you speak Hendrix when you went out with them?

BENJAMIN: No. Well, I cheated to be honest. I did not. I did not. I did not. I was, you know, just me. I mean, at times I would break into it, but for the most - you know, I was getting to know them. I was nervous, you know, they were true actors and - you know, so my nerves had to go at first, but yeah. That was the best thing for this movie, so I didn't have to jump on screen and act like I knew these women. Like, I actually knew them and thought they were cool and, you know, there was an attraction there. So it was, you know, it could be seen on screen.

GROSS: Can you tell us about learning to play guitar like Hendrix? It's a left-handed guitar. He plays with his teeth, he plays with his guitar behind his back. I mean, and plays brilliantly of course. So we're not hearing you play guitar...

BENJAMIN: Right.

GROSS: ...But we're seeing you play it. So what did you have to learn?

BENJAMIN: Everything.

GROSS: (Laughter).

BENJAMIN: I'm just being honest. I had to learn everything from playing behind my back to playing with my teeth to rolling around on the ground playing. I watched all the footage and I mimicked everything to the T, just to have it in the arsenal just in case we needed it. But, you know, one of the hardest parts, I'm a right-hand guitar player, like, I'm a horrible right-hand guitar player. I wouldn't even call myself a guitar player. I just pick it up and fiddle with it every now and then. And I think any guitar player would agree with me, like, Jimi is the most comfortable looking guitar player in the world. Like, I've seen a lot of great guitarists that are probably, like, much better and, you know, much better skilled guitar players than Jimi Hendrix, but they - some players look like they're doing a task or working, you know, an instrument, like, actually putting in a lot of work, like giving a lot of effort. One thing about Jimi, he never looked like it was uncomfortable to him, ever. So one thing I was concerned about is making sure that it looked like I was playing with ease because the way he strapped it on, the way it fit on his body, it just - it was almost like it was meant for him to play. So when it came down to doing the left-hand thing, I just had to, you know, it was almost like finger choreography. It was learning where the chords are, learning the actual chords of the song with my left hand, learning where the notes are, learning how my fingers should lay. But it was really, really difficult because it's almost like walking backwards, and making walking backwards look normal.

GROSS: Right.

BENJAMIN: That's what it was like.

GROSS: Andre Benjamin and John Ridley will be back in the second half of the show. Ridley wrote and directed the new film "Jimi: All Is By My Side." Andre Benjamin stars as Jimi Hendrix. Here's a performance scene, set at London Saville Theatre, where Hendrix makes a gutsy choice performing the title song from the newly released "Sergeant Pepper's" album with members of The Beatles in the audience. Andre Benjamin does his own singing. I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "JIMI: ALL IS BY MY SIDE")

BENJAMIN: (As Jimi Hendrix) (Singing) It was 20 years ago today, Sgt. Pepper taught the band to play. They've been going in and out of style, but they're guaranteed to raise a smile. So may I introduce to you the act you've known for all these years. Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. We're Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. We hope you will enjoy the show.

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. We're talking about the new film "Jimi: All Is By My Side," which is about one year in the life of Jimi Hendrix between 1966 and '67. When he was living in London where he developed his sound and started recording albums with his own band, The Jimi Hendrix Experience. I have two guests. John Ridley wrote and directed the film, and won an Oscar for writing "12 Years A Slave." Andre Benjamin stars in the film as Jimi Hendrix. He's also half of the hiphop duo Outkast.

When Jimi Hendrix gets to England he's used to being a side man or, you know, playing covers. He's not yet - at least not as described in the film - a magnetic performer in the same way. He doesn't think of himself as a star. So this is a very transformative period of his life and the way the film tells the story, one of the key things that happens to him is that Linda Keith - who had been Keith Richards' girlfriend - realizes Jimi Hendrix's potential. And not only gets in a good, you know, great guitar, but also coaches him and says to him things like - you have to learn how to take the stage, and look like you really want to be there, and you're really comfortable there, and don't pick at your skin when you're on stage. Are these things that she told you?

RIDLEY: Yeah. I mean, I would say this - and I will say this about Linda Keith - Linda Keith Porter now one of, in my opinion, one of the unsung heroes of rock-and-roll. And one of the most humble individuals, someone who at 19 years old, you know, walked into a club, saw Jimi Hendrix backing up in an okay band, and realized the potential that this individual had. And at 19 went around, brought other managers and producers and record executives to see Jimi play. And, you know, time and again nobody bought into him, and what he was doing and finally introduced him Chas Chandler who got him together with Noel and Mitch, and Michael Jeffrey who ended up being one of his other managers. You know, Jimi Hendrix at 24 years old was kind of washed up. He'd play with Ike and Tina Turner, played with Isley Brothers, played with Little Richard and because he was a true individual never really fit into other people's style. There's a really good chance that Jimi Hendrix, because of his capacity, because of his artistry, could've gone on to have been a star in some fashion. But I think it's very fair to say that were it not for Linda Keith, the Jimi Hendrix that we know probably would not have existed.

GROSS: Do you think he was that way on stage as described in the film, where he was actually, like, picking at a skin on stage and not really thinking about what you have to do on stage to be magnetic?

RIDLEY: Oh, yeah. I mean, it was one of those things where he had an innate quality and if people were really looking at the way he played and how he played you could see it. You know, if you are an individual, but you end up in spaces where continually you are told do not be individualistic, you're not going to get head that way, just sort of play the game and fit in after a while that kind of beats you down. And sometimes it does take other people to say, you know, look one of the things that people would say to him is, you know, you got to sing. You got to take ownership of your performances. And he never really liked his voice. And one of the people who really encouraged him, you know, Linda Keith would say to him, you know, look, Dylan doesn't have a great voice either, but it's not about the sound of his voice; it's about the passion that he puts into his singing. And really helped drive him to a place, him being Jimi, where he had more confidence and took more ownership of the material. Chaz was the same way as well, but it was a cascade of individuals who came into his life and said, look, you have the abilities, you just got to take ownership of your artistry.

GROSS: The way he's described in the film, he's so kind of like low-key and soft-spoken and kind of withdrawn offstage. And on stage, once he gets the hang of it, he's really on fire. And Andre Benjamin, as a performer I'm wondering if you know a lot of performers who are like that? Who are so alive on stage and so much more withdrawn off?

BENJAMIN: Oh, definitely, definitely. I think with a lot of performers, and you'll see it. It's kind of like a - it's playing cowboys and Indians. It's like if you're a child and the stage is kind of like that place where you go for it and then when you're off stage you can be a completely, you know, reserved individual. You know, I'm that way. Like sometimes on stage it's kind of like you're just going and having a good time and seeing where you can go with it, because it's the place where you're just open. And, you know, like, comparing it to cowboys and Indians and if you're in your room and you're having this war in your head and, you know, got these toys and you're (sounds), all this kind of stuff, when his moms opens the door, the veil is kind of lifted.

GROSS: (Laughter).

BENJAMIN: You're back to the normal world, so, you know, once the amps go off and all that kind of stuff and you walk down the steps from the stage - yes, it's a different thing. And you're kind of back into reality in a way, so I know about that. And Hendrix, you know, he wasn't that confidence to start with. It's been documented. He didn't, you know, even the first time in the studio, like, he was amazed, like, scared at his own voice coming out of the microphone. He didn't want to be the lead, man, he didn't. So, you know, he was just shy in that way, but at the same time he had a confidence in his plan and he knew it. I heard interviews where you could hear, you know, he was kind of cocky. At certain times about his guitar playing when people tried to compare him to other players. But I think his vocal ability he wasn't too sure about, and, you know, I can say I've been there before. Like, first Outkast shows - they were kind of like, you know, I hardly could move because it's a new thing. And you got to get used to it, but once you've done it, you know, for a while you kind of get into your own confidence and we see that in Hendrix in this movie.

GROSS: My guests are John Ridley, who wrote and directed the new film "Jimi: All Is By My Side," and Andre Benjamin, who stars as Jimi Hendrix. We'll talk more after break. This is FRESH AIR.

(MUSIC)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guests are John Ridley, who wrote and directed the new film "Jimi: Always By My Side," which is about one year in Hendrix's life. The year that he was in England, right before going to the Monterey Pop Festival and becoming a star. He also wrote "12 Years A Slave." Also with us is Andre Benjamin, who's best known for his work in the band Outkast and he plays Jimi Hendrix in the movie. So there's a central scene in the movie in which Jimi Hendrix and one of his girlfriends go to buy marijuana from a dealer whose named Michael X, who's from the islands. He's from one of the Caribbean islands. And Michael X passes himself off as someone who's, like, very political. And he wants Hendrix's music to be more political or else he thinks - Michael X thinks - this music is trivial. Let me play an excerpt of that scene.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "JIMI: ALL IS BY MY SIDE")

ADRIEN LESTER: (As Michael X) And look, you know, I'm saying this brother to brother, all right? You'll never be nothing to them but a curiosity. And that's - that's the truth. They don't let you upon that stage, they want you up there. Their electric wolf.

BENJAMIN: (As Jimi Hendrix) Well, that's cold man.

LESTER: (As Michael X) All right, look, you're fooling around with all these white kids, but it's Black British who need someone to inspire them.

BENJAMIN: (As Jimi Hendrix) (Laughter) Inspire man.

LESTER: (As Michael X) Why is that funny to you? You could be a symbol.

BENJAMIN: (As Jimi Hendrix) You don't even understand. What are you talking about?

LESTER: (As Michael X) You could - you could be a symbol.

BENJAMIN: (As Jimi Hendrix) I'm just playing my guitar.

LESTER: (As Michael X) Play music to your people.

BENJAMIN: (As Jimi Hendrix) Oh, my people? They're all my people. Every last one of them, they're my people.

GROSS: So that's a scene from the new Jimi Hendrix movie "All Is By My Side." So John Ridley, you wrote and directed the film. Andre Benjamin, you play Jimi Hendrix. Have you been through that dialogue in your life and work? And have you played that dialogue within your own mind? Have people confronted you with, like, no it's got to be political? So I'll ask you each to talk about that starting with you John, since you wrote the screenplay.

RIDLEY: In some fashion or another, yes. People have stepped to me with expectations about the work, about what I'm saying or conversely, sometimes hard reactions about the things that I've written, particularly when I've written for places like Esquire or I've had the opportunity to do pieces for NPR. You know, people have expectations one way or the other. You should do this, you should do that, say this, say that. And I do think there comes a point where - for anyone - if you are in a space, particularly as a writer, you go into this craft because it is about self-expression and not merely expressing things that other people want.

GROSS: I imagine a lot of people thought that "12 Years A Slave," for which you wrote the screenplay, was more what you should be doing because it's a much more, you know, political, social, economic film? It's not a crime film, it's not a music biography.

RIDLEY: You would be - one would be surprised at how many people had a problem with "12 Years A Slave" for various reasons. You know, there are people who thought that it was a torture porn. There were people who thought that it was just exacerbating race issues in America. There are some people who thought that it was just another film about downtrodden people of color. That if we were going to do American history or American history that focused on Black Americans, you know, why go back to slavery? There are - it's just a reality. If you do things in a public space, no matter what you do, there are going to be people who disagree with that, as is their right. And - as is their right to be vocal about it. But if, you know, if you go into the things that you do by measuring yourself by other people's limitations, either the limitations for them to do things or limitations and their expectations for yourself, I mean, what you end up doing? You end up doing nothing.

GROSS: And Andre Benjamin, how has that argument between doing something politically, socially conscious and just doing whatever it is that you love, whatever music you love, how is that argument played out, if it all, in your life?

BENJAMIN: Well, I think with music more than any other art category, I think, you know, the fans feel like you have to speak for them or you have to have a - you have to represent a certain thing. So I have definitely been approached, you know, with saying, you know, hey, what's going on with the white boy songs? You know, especially with, you know, after the second album, which was "ATLiens." You know, our career kind of went a certain way and you start to see, you know, more white faces in the crowd. And it's kind of like with - kind of like the Black community, they just feel like if it's not straight ahead or if it's not talking about the neighborhood or it doesn't have a certain sound, then it may not be for them. And I've always - when I got into the music, I didn't get into it for one certain thing. I got into it because it was fun, I got into it to stretch out just to see how far I could go with it. So, you know, I kind of - it does agitate you because of course you want the support of the people from the places that you're from. You really want that. But once again, it's more important for me to do - to be all I can be in the music. And as long as I can touch people with music, I don't care, like, what's your color or anything like that.

GROSS: What about you? Do you identify with Hendrix not wanting to be defined by a certain style or defined by being African-American?

BENJAMIN: I would have to say with music it's just - it's sad that, you know, you have to get to a point where some people try to separate it and say, you know, I'm making this music for, you know, this race of people. I don't think there should be any of that in it. Unfortunately, I grew up in a hip-hop era where, you know, there are certain kinds of things that kind of keep you caged, where, I mean, I remember, you know, being young and, you know, if you said certain things or you spoke a certain way or if you spoke intelligently, you were considered, you know, not as cool, you know, in the Black community. And, you know, my upbringing was kind of odd because it was kind of like a double life. You know, you live like on the West side of town in Atlanta, you know, across the street from Bowen Homes projects. And you would - I would get on the bus and it was like a first year they had an M&M program where they would take kids from these neighborhoods and take them to Buckhead where, you know, that's where the mayor's kids and, you know, the governor's children were going. So I would go to, like, Sutton Middle School so I would be, you know, coming from this side of town, you know, going to this other side of town being turned on to, you know, white bands, you know, skateboarding, all that kind of stuff. And it was almost like a double life. So I'd get - I'm actually glad that my mom did it that way so I could see two - two sides of everything so I wouldn't kind of lean so far with either one and kind of side with it all.

GROSS: So let me ask you about what you're doing now or what you've done recently, Andre Benjamin. You've been performing on tour with Outkast. What's it like to be back in Outkast and doing a lot of the songs that you did, you know, a few years ago?

BENJAMIN: Oh well, it feels great, you know, to be on stage and see the - see the fans get into it. And at this point, you know, that's really what it's about. You know, just to know that, you know, these are songs that people grew up with. And I'm a fan of music, so I know how that feels to kind of - to take a song and relate it to a certain incident in your life and it becomes a part of your life. So for me to be able to go out there and do it, you know, it's a great thing. As, you know, as an individual, as an artist, it feels, you know, a little bit different, you know, because the songs just mean a little bit different to me now then, you know, when I was like 19 or 20 or, you know, even when, you know, when we originally wrote songs like "Bombs Over Baghdad" and performing them at that time, it meant something completely different. The energy was completely different than, you know, me being 39 now. So, you know, at this point, you know, it's a - it's a presentation, you know. It's giving back in that way. But it's been such a great thing. I'm glad it happened because man, you just get to see all of these people that love the music. And I think it's funny because you get these new kids that are into it because there's like '90s resurgence. So I know when we were out in the '90s, we were just enamored by people from the '70s. So, you know, it's always like this kind 20-year kind of...

GROSS: The period you just missed, yeah.

BENJAMIN: Twenty-year kind of thing. So now, you know, it's 2014 and, you know, kids are like oh man, so - they want to know more about Nas, they want to know more about Wu-Tang and they want to know about Outkast. You know, it's like, you know, that was a different time for them. So you see all these young faces singing these songs, but then you see like 50, 60-year-old people actually singing them too. So it's just - one thing I can say, I'm just happy that we have that range of fans, you know?

GROSS: Years ago, you know, you said you didn't want to still be doing rap when you were in your 40s. You sing a lot.

BENJAMIN: Right.

GROSS: You don't just do rap, you do a lot of singing. But what's your stance on that now that your 40 - or 39, about to be 40?

BENJAMIN: Yeah, I mean, I - you see the thing of - and I think there was a story that came out in the New York Times - they were, you know, speaking retirement and this kind of thing. One thing I've learned as a rapper and every rapper should know this, you know, there's retirement and rap. Those two words just do not go together, you know, so, you know, it's honest. But I can say at 39, I mean, I'm not rapping like that. I don't think about it. I'm not on it, like, I mean, my competition level is not - I don't even care in that way. It's not any disrespect to the genre, it's just like life moves on. And, you know, I love this music genre so much, like, I'll leave it to the people that are gung-ho about it that are like in it every day because I know what it feels like to be in it every day. And at 39, I just don't feel the same. I mean, but if I - can I wake up tomorrow and have a thought and write it down and it rhymes? Yeah. And if that happens, you know, I'll put it out. But there are rappers that are, you know, well in their 40s still doing it. And my thing is it's a personal experience. It really - to me it's about what are you getting out of the music? Why are you doing it? So I just want to make sure what I'm doing is honest to my age and honest to my time. Like I ain't in the street like that. I mean, I've never been in the street like that. My mom raised me well. I mean, my cousins have been in the street, you know, because of my - where I live in Atlanta. I was in the street in that way, but it was more through people that I knew. You know, so it's not like I have something to keep up or, you know, I'm trying to be 40 years old and act like I'm banging and killing people or something like that. Like, that's just - that's just not my reality man. Like, I'm 39 years old with a 16-year-old kid man, trying to figure out what he's going to do. And so, you know, rapping to me - I love rap. I love the stupidest of the stupidest rap, like - but also I can go and listen into Thelonious Monk at the same time. So I'm just a music fan, period. So as long as I'm doing something that's honest to me, that's what's most important. And I think if the fans, you know, if they're with it, they're cool. You know, if they don't - if they don't dig it, you know, they can tell me to go to hell. I'm cool with that.

(LAUGHTER)

BENJAMIN: I'm totally cool with it.

GROSS: And John Ridley, I know you have a couple of projects in the works now. Tell us about one of them.

RIDLEY: The thing I'm working on most centrally right now is a series for ABC television called "American Crime." And it's - it's really been an interesting couple of years. You know, in the last three years having worked on "12 Years A Slave" and "All Is By My Side" simultaneously, and particularly writing and directing it, and then, you know, as you know, "All Is By My Side" is an interesting film and eclectic film. It has a very, I think, unique language of cinema that it uses. And you're not sure how people are going to perceive it except that you put a lot of passion into it. And ABC asked me to write a series - this series "American Crime," which is about a crime that's really looked at not about the evidence or the law, but through perspectives of race and class and socioeconomic perspectives. But they saw the film "All Is By My Side" and they loved it. They loved what we were doing. They loved the use of cinema and they said oh, we want you to - we want you to bring that to broadcast television. And when someone offers you an opportunity like that, to not just tell a story, but tell it in a unique way and tell it in a way that has an opportunity to reach so many people, you know, you can't help but jump at it. And it's been a wonderful experience thus far. And we're going to actually premiere next March.

GROSS: Oh, great.

RIDLEY: So we're about halfway through production.

GROSS: Fabulous.

RIDLEY: It's pretty terrific.

GROSS: Great, I look forward to seeing it. I want to thank you both so much. John Ridley, Andre Benjamin, thank you and congratulations on the film.

BENJAMIN: Thank you.

RIDLEY: Thank you for having us.

GROSS: John Ridley wrote and directed the new film "Jimi: All Is By My Side." Andre Benjamin stars as Jimi Hendrix. Coming up, Maureen Corrigan reviews the new novel by Sarah Waters, set in post-World War I England. This is FRESH AIR.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. Novelist Sarah Waters has been shortlisted three times for the Man Booker Prize and she's been named one of the best, young British novelist by the journal Granta. Book critic Maureen Corrigan says that Waters should expect more prize nominations, and possibly a win this time for her latest novel "The Paying Guests." Here's Maureen's review.

MAUREEN CORRIGAN, BYLINE: Sarah Waters' new novel "The Paying Guests" is a knockout, which isn't a word any of her characters would use. Water's novel opens in 1922. The Edwardian age with its high collars and long skirts is dead. The Jazz age is waiting to be born. At least that's the case in the suburban, backwater of London where Waters' main character - a 26-year-old spinster named Frances Wray - lives with her mother. The Wray women have decidedly come down in the world. Frances' two brothers were killed in World War I, and her recently deceased Papa made some bad investments. Raised to be a middle-class gentlewoman, Frances now cooks up inferior cuts of beef, and empties bedpans, and rubs her knuckles raw scrubbing the hallway floor.

If "Downton Abbey" needed an extra slavey (ph) to work in the kitchen alongside Mrs. Patmore, Frances is more than qualified. But "The Paying Guest" is no simple, period peace. As alert as Waters is to historical detail, she's also a superb storyteller with a gift for capturing the layered nuances of character and mood. Any reader familiar with Waters' earlier novels - like "Tipping The Velvet" - will know that she's especially drawn to the subject of lesbian relationships. What's so immediately compelling about our protagonist - Frances Wray - is that, in a way that doesn't seem at all anachronistic, she's comfortable in her own the queer skin. It's most of the rest of the world, and tragically some of the people in her own house, who have serious problems with Frances and her so-called unnatural sexuality. Waters structures "The Paying Guests" like a modern updating of the standard, 19th-century three-volume novel. The entire story is spellbinding; but I particularly favored part one, with its oppressive, pre-thunderstorm air of anticipation.

When the novel opens, Frances and her mother are awaiting the arrival of a necessary evil - lodgers whose rent money will help the raise hold onto their large, dark house in South London. Those lodgers - or paying guests - are a married couple, Lillian and Leonard Barber, whose refined elocution-class accents mark them as less-genteel-by-birth than the Wrays. In delicious detail, Waters has Frances register the change in atmosphere in the house as the invading Barbers stakeout their territory. While Francis was out in the kitchen assembling a cold, Sunday supper the couple came down and tapped at the door. The water closet was an outside one, and they had to pass through the kitchen to get to it. They came grimacing with apology. When Mr. Barber headed back upstairs she heard him pause in the hall. Wondering what could be delaying him, she ventured a look along the passage and saw him gazing at the pictures on the walls, like a man in a gallery leaning in for a better look at a steel engraving of ripen Cathedral.

He put his fingers to his pocket and brought out a matchstick with which he began idly picking his teeth. Slowly, other kinds of trespasses into private territory take place here. I don't want to reveal much more of the plot - because one of the great pleasures of Waters' ambitious story lies in its slow unfolding, which readers should be allowed to relish for themselves. And speaking of things to relish, as evocative as Waters is in describing more intense moments - like say the giddiness of fresh, sexual attraction - or the violent anger of ex-servicemen panhandling on a London street - she also excels at capturing the mundane.

Day after day, the hours slowly pass in the Wray's shadowy house, where three women - Frances, her mother and Lillian Barber - are entombed. Money is too tight for entertainments, paying jobs for ladies are still frowned upon and only volunteer work at the church bazaar beckons. The Wray's house itself is a presence here - full of unrelenting, daily demands of cleaning, waxing and endless dusting. Frances thinks to herself that the house must produce dust as flesh oozes sweat. When Francis admits passion, the ultimate intruder into that dull house - chaos - erupts. "The Paying Guests" is one of those big novels you hate to see end. Especially since you sense the end might be a very nasty one indeed.

GROSS: Maureen Corrigan teaches literature at Georgetown University. And is the author of the new book "So We Read On: How The Great Gatsby Came To Be And Why It Endures." She reviewed "The Paying Guests" by Sarah Waters.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.